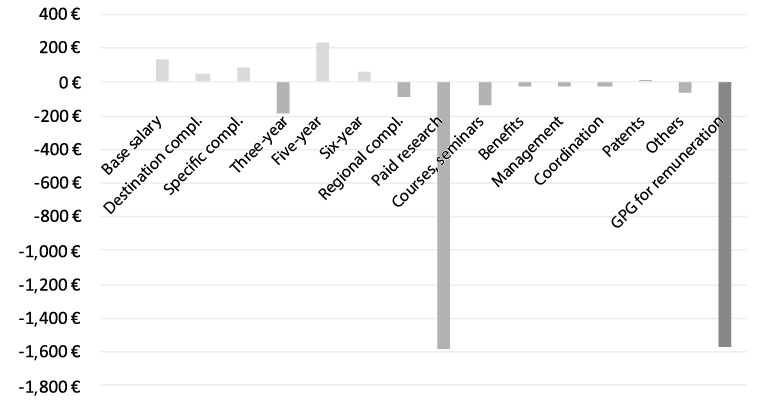

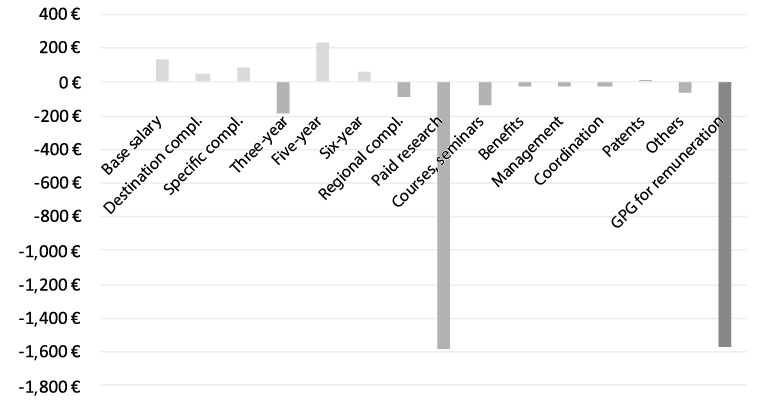

Graph 1. Contribution of salary complements to the gender wage gap among tenured professors

Source: By authors based on data from Jabbaz (2023).

doi:10.5477/cis/reis.190.129-146

The Direct and Indirect Gender Pay Gap: Contributions for Its Measurement

at the University

La brecha salarial de género directa e indirecta.

Contribuciones para su medición en la universidad

Marcela Jabbaz Churba and Mónica Gil Junquero

|

Key words Gender Pay Gap

|

Abstract The gender-pay-gap (GPG) is currently a socially relevant issue. This study has two objectives: 1) specify theoretical-methodological factors that intervene in the conceptualization and measurement of the GPG and its components, identifying the direct and indirect dimensions of the GPG and provide guidelines for its calculation in organizations; 2) Present an analysis of the gap at the University of Valencia with payroll data from 2021 and its comparison with 2015. Among the main results, we propose the GPG as a synthetic indicator of inequality that brings together the effects of the different trajectories of women and men. In addition, we find the existence at the University of Valencia of discretionary cracks that filter a normalized discrimination, forming a persistent, systematic and widespread gap. |

|

Palabras clave Brecha salarial de género

|

Resumen La brecha salarial de género (BSG) es actualmente una cuestión socialmente relevante. Este estudio plantea dos objetivos: 1) precisar elementos teórico-metodológicos que intervienen en la conceptualización y medición de la BSG y sus componentes. Se busca identificar las dimensiones directa e indirecta de la BSG y brindar recaudos para su cálculo en organizaciones; 2) presentar un análisis de esta brecha en la Universitat de València (UV) con datos de nóminas de 2021 y su comparación con el 2015. Entre los principales resultados, por un lado, proponemos la BSG como un indicador sintético de desigualdad que aglutina efectos de las diferentes trayectorias de mujeres y hombres. Por el otro, se observa que en la UV existen grietas de discrecionalidad que filtran una discriminación normalizada, conformando una brecha persistente, sistemática y generalizada. |

Citation

Jabbaz Churba, Marcela; Gil Junquero, Mónica (2025). “The Direct and Indirect Gender Pay Gap: Contributions for Its Measurement at the University”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 190: 129-146. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.190.129-146)

Marcela Jabbaz Churba: Universitat de València | marcela.jabbaz@uv.es

Mónica Gil Junquero: Universitat de València | monica.gil@uv.es

Introduction1

Actions to reduce the gender pay gap (GPG) in universities and in other organizations (public administrations, third sector entities and companies) have gained traction and its study has become socially relevant. Feminist demands on this matter have been enshrined in new legislation in Spain, mainly in Royal Decree 902/2020, of October 13, on equal pay between men and women and, specifically in universities, in Organic Law 2/2023, of March 22, on the University system (known as the LOSU). The former encourages companies and organizations to apply the principle of pay transparency, establishing the obligation to create an accessible pay registry disaggregated by sex and a process of pay audits. The LOSU obliges Spanish universities to develop impact reports based on gender in their budgets, and specifically the analysis of expenditure items related to personnel, which implies measuring the GPG.

In this context, this study has two objectives. The first is to examine the theoretical and methodological factors involved in conceptualising and measuring the gap and its components. This also allows for the comparison of the GPG in different universities and organizations. The second is a specific analysis of the GPG in the University of Valencia (UV)2, using payroll data from 2021 and comparing the results with those from a study carried out in 2015; note that we find this gap is persistent, systematic and widespread in the UV.

The first section provides theoretical reflection on the factors that are at the root of the GPG, developing the concepts of a structural gap and a reproduced gap. We also find that both direct discrimination, linked to employment position, as well as indirect discrimination, produced over the course of academic trajectories, are at the origin of the GPG. We return to the idea that bureaucracy is affected by discretionary cracks3 (Jabbaz, Samper and Díaz, 2019) which normalise practices without awareness that they discriminate against women.

In the second section, a methodological approach is introduced that contributes to the current debate on the calculation of the GPG. A definition of the units of analysis for calculating the overall GPG is presented in order to avoid measurement errors in micro, organizational-level analyses, such as studies of the GPG in universities. Clearly defining the units of analysis within and between universities improves the validity of comparative studies because it isolates the GPG from wage effects arising from differing personnel structures across universities.

We then present as a case study an analysis of UV salaries in 2021. The GPG values obtained in that study are different from those found in the recent statewide study of public universities by Martínez Tola et al. (2023) because the definition of the units of analysis is different and, as we will see, in our case, more narrowly focused.

As a result, our study of the GPG reveals some keys to approaching its study, dismantles certain myths and provides indicators that in a dialogic and unfinished process, can help us move towards more egalitarian institutions.

A theoretical approach to address the gender pay gap

The GPG is a complex measure. It is an expression of an existing inequality, as women and men receive, on average, different salaries. At the same time, it is a synthetic measure, an indicator, that connects with multiple inequities, for this reason, it is the measure of an outcome (a consequence). The GPG results from both current and past gender relations, which originate in different spheres.

The GPG is based on discrimination that originates outside of the academic institution, produced in the private sphere; and other discrimination that originates within the institution, the fruit of social practices, habits, formal and informal norms, values and hierarchies that are installed within it. Organizational spheres constitute gender regimes that (re)produce material and symbolic inequalities (Connell, 1996) and masculine behavioural patterns (Acker, 1992). Success within this sphere is often oriented towards criteria of efficiency and competition, obscuring other values, such as co-responsibility. These patterns have a different impact on women’s and men’s trajectories, generating the GPG. We concur with Acosta Revelles (2021) in aggregating other dimensions to the origin of inequalities in academia, given that gender intersects with other systems of oppression linked, among other factors, to social and ethnic origin.

Theories of human capital (Blinder, 1973; Oaxaca, 1973; Becker, 1993 [1964]), anchor the explanation for wage difference by gender in women’s own characteristics, such as education, merit, lack of confidence and personal preferences. These theories have been questioned for their subjective character considering that gender relations are the conditioning factors (Drolet and Mumford, 2012; Sánchez-Vidal, 2016; Babock, 2017. However, the idea of merit as the standard for wage differentiation persists in the androcentric imaginary, and in academic cultural struggle, which remains resistant to equality (Martín Bardera, 2018).

In their study, Frieze et al. (2006) highlight that motivation and commitment to work have an impact, independently of gender, on salaries, but these factors do not explain why men continue to earn more than women. Individual initiative and motivation would influence pay differences between individuals, but do not explain the GPG as a systematic, persistent and widespread phenomenon, more connected to structuring aspects of the asymmetrical relations between women and men in academia. These persistent pay differences between women and men are better explained by inequalities in family responsibilities, dominant gender roles and stereotypes, restrictions on mobility in scientific fields and sexist practices within organizations, among others.

The problem of pay discrimination has, for some time now, been addressed through legislation and by different social agents. The changing economic circumstances that emerged after World War II with the increased presence of women in formal paid work, led the International Labor Organization to approve Convention 100 on pay discrimination which in its first article states:

a) the term “remuneration” includes the ordinary, basic or minimum wage or salary and any additional emoluments whatsoever payable directly or indirectly, whether in cash or in kind, by the employer to the worker and arising out of the worker’s employment; b) the expression “equal remuneration for men and women workers for work of equal value” refers to rates of remuneration established without discrimination based on sex.

The convention advises that all payments (direct or indirect) are part of remuneration and promulgates the principle of equal pay for work of equal value, independently of the sex of the person who carries out the work. However, since then, other important developments have occurred. In the Fourth World Conference on Women (Beijing, 1995) the deep, structural, naturalized, and therefore invisible, nature of gender inequality was stressed. In addition to regulating direct and visible discrimination, the necessity to address indirect discrimination was emphasised; the latter, when applied to wages, no longer refers to supplementary payments or payments in kind, but goes beyond that. It refers to the situation in which an apparently neutral provision, criterion or practice places persons of one sex at a particular disadvantage with respect to persons of the other. In European legislation, this concept is applied to discrimination based on sex (Freixes Sanjuan, 2008) but also on the basis of ethnicity and other factors (Arcos Vargas, 2022). In Spanish legislation indirect discrimination is included in Organic Law 3/2007 on the effective equality of women and men.

Therefore, when speaking of the GPG, while there is clearly direct wage discrimination in the workplace based on sex (as indicated by the ILO), indirect discrimination operates in a complementary manner, impacting the trajectories of women and men in academia. The two forms of discrimination shape two dimensions:

Both gaps result from the structural inequalities in society and within institutions.

To approximate our terminology to that commonly used in the literature, first, we consider the direct GPG to coincide with what is referred to as the adjusted GPG. In the case of teaching categories in universities, the base salary and specific and assigned complements are established by law, equal for all employees, independent of gender. However, as we will see in our case study, the GPG within employment categories is found in other, less regulated components, such as emoluments originating from contracted research, and the organization of courses and seminars beyond contractually established teaching obligations. As a result, in a highly regulated bureaucratic organization such as the Spanish university, discretionary cracks (Jabbaz, Samper and Díaz, 2019) appear, which, are not random, but follow discriminatory patterns.

Even when each work task (and each salary complement) is paid based on its value, the organizational structure and its context (including formal and informal rules) generate varying opportunities to access these supplements that, on average, privilege men. The systematic study of the contribution of these supplements to salaries to the GPG provides indications as to where inequalities may be occurring.

Secondly, the indirect GPG has an impact on the formal remuneration system and is often referred to as the unadjusted GPG, but here will be referred to as the overall GPG. It refers to discrimination produced over the course of employment trajectories and, therefore, includes the effects on wages produced by internal and external barriers that hinder the promotion of women in scientific careers - the “glass ceiling”, that is, the invisible threads that limit women’s access to leadership and management positions in the university. Likewise, constraints related to work-life balance lead to slower trajectories for women and a loss of talent (the so-called “leaky pipe”) for institutions; this often results from the abandonment of paid work to provide care in the family sphere.

In this way, the analysis of the GPG allows us to observe the economic circumstances of those who occupy jobs today, but it is not limited to this, as it is a measure that reflects the discrimination produced throughout women’s and men’s trajectories in work spheres with their own wage logics. This allows for a systemic, structural and comprehensive approach to gender-based wage discrimination.

General methodological contributions to the measurement of the GPG

Studies on the gender pay gap produce information based on the analysis of payroll data at a given point in time. However, as we have mentioned, the GPG is an indicator of inequality that reflects discrimination that occurred at a time prior to the data. Here, we provide some reflections on employment trajectories because gender inequalities as measured in the overall GPG originated over time.

When speaking of trajectories, we refer to the path or journey taken by individuals within an employment field, therefore, the trajectories are personal, specific and different from one another. To analyse a trajectory involves observing the path that an individual has followed (their footprint or steps) and the distance (how far they have come, what the obstacles and achievements have been).

In contrast, the organizational field is the path (the substrate), i.e., the structuring aspects (norms, rules for access and promotion), the possibilities that the organization provides access to. Thus, the field is the symbolic territory where confrontation, cooperation and/or the construction of friendships and relationships between persons in academia are produced in occupying positions. The field is the symbolic substrate, meanwhile the collective or group is integrated by individuals who work in the field. For example, the field of full-time faculty would be configured by all the rules that regulate it; while the employment group would be all the individuals that hold a position in the field and realize their professional trajectory within it.

Based on these premises, certain methodological caveats must be considered that are determinant in obtaining plausible results.

First, the methodology is different when working with a survey that measures the GPG taking the individual worker as the unit of analysis, as opposed to a study of the GPG that analyzes the complete salary structure in an organization (in our case, universities). For example, our analysis is different from the macro wage gap studies carried out with the Wage Structure Survey of the National Institute of Statistics (Simó et al., 2023), which utilizes a sample of establishments and workers4. The difference lies in the observation that follows, which is linked to the personnel structure of the organizations.

Secondly, if the GPG is analysed taking all the workers in an organisation as a unit of analysis, the measurement of the GPG must be done separately for each of the occupational groups that share the same trajectory. The identification of these groups in the study of organizations has to be a prior methodological step if we want to obtain a valid measurement of the overall GPG, in order to isolate (separate) what corresponds to the salary effects of gender discrimination within a trajectory, from other salary differences produced by different types of hiring contracts.

A recent study of the gender pay gap in Spanish public universities (Martínez Tola et al., 2023) did not segregate by groups to calculate the overall GPG but obtained this data by calculating it on the basis of the entire staff holding teaching and research responsibilities. Although this study homogenized the working day of part-time and full-time faculty by means of a coefficient, the problem lies in the fact that the measurement is made on groups of employees that do not have the same status or the same academic career or trajectory. As a result, there are significant salary differences between these groups of teaching and research staff (for example, between Associate and Full-time Professors) that are not, strictly speaking, based on gender.

This is particularly important when universities are compared with one another, as they have different hiring structures and different proportions of part-time and full-time faculty. The calculation of an overall GPG without differentiating by employment group would not only include gender discrimination produced over perfectly defined trajectories but would be contaminated by the influence of the proportions of faculty hired under different contract types.

Thirdly, it is worth noting that the overall GPG will always be greater than the gap adjusted by category, because the overall gap includes different categories (within the same field/group) and, therefore, subsumes a larger quantity of possible inequalities, both past and present. In addition, the largest part of the overall gap has been a long time in the making (the scissors diagram reflects several generations of male and female academics). Thus, we can say that the overall GPG gap is a gap from an inherited structure, and more difficult to eradicate, because it reflects the hierarchical order of the institution (the “glass ceiling”) and, therefore, the under-representation of women in the highest categories (full professorships and chairs).

Fourth, the gap adjusted by category permits us to focus on varying components (courses, conferences, research grants, academic positions, among others). Therefore, we can categorize this as a gap that is reproduced by stakeholders within the organization that currently continues to reproduce inequality due to differential participation in a gender-biased opportunity structure. This means that, despite its normalization, it is possible to introduce new regulations and take positive actions5 to make the opportunity structure more equitable for both women and men.

Lastly, we can characterise gendered trajectories or typologies of women’s and men’s trajectories by examining the conditioning factors placed on subjects limited by their belonging to a particular gender, social class or other subalternity, which determine a range of possibilities (and limit others). In addition, the age in which someone enters a field and the “breaks” that may occur in an academic career are factors that can penalise or reduce opportunities for academic achievement.

The aim of this section is to analyse the overall and adjusted GPG of faculty at the University of Valencia (UV) using the 2021 payroll database. In addition, we analyse the impact of variable components of compensation on the overall GPG. Finally, we compare the data for the overall GPG from 20156 with the corresponding data from 2021, as well as with the results of the aforementioned study on the GPG carried out at the state level in 48 universities (Martínez Tola et al., 2023).

The current case study uses some of the theoretical approaches and methodological caveats of the previous sections.

Methodology behind the case study

The definition of our units of analysis

An initial decision was to carry out the study on those holding positions requiring teaching and research, in Spanish referred to as Personal Docente Investigador, and here considered as academic positions, or simply faculty, which excludes separate research staff (interns and grant-holders whose salaries are regulated by widely different calls for positions) as well as administrative and service personnel.

As previously mentioned, for calculating the overall GPG it is necessary to clearly identify the organizational fields and groups employed within the organization on which the measurement and analysis will be carried out. Defining this requires knowledge of the formal and informal rules that govern the establishment of the shape or boundaries between different collectives of faculty employed in the university.

Therefore, among the faculty we identify three collectives with clearly differentiated trajectories: 1) Adjunct faculty, 2) Full-time faculty and 3) Attached faculty. Thus, the overall GPG is analysed based on these three academic groups or units of analysis, each formed by homogenous professional profiles and salaries.

The position of adjunct professor refers to specialists and professionals that carry out their main professional activity outside of the UV and are needed by the university when there are specific teaching needs related to the individual’s professional sphere. They are contracted to work part-time under different regimes, never exceeding 120 teaching hours per academic year. The salary received from the UV only reflects income specific to the teaching tasks they carry out for the university.

Adjuncts constitute the second largest number of UV hires, with a total of 1852 and an approximately equal representation of women and men. The average age of the group is 48.7, though women in this group have an average age of 47.5 (see Table 2).

Full time faculty are those who have a full time dedication to teaching and research at the UV. There are different employment categories7 among full time faculty, some of which are specific to the Spanish university system or even to the regional university system and we do not find exact equivalents in other university systems. For our purposes, though full time faculty are governed by different employment and labour regimes and different salary scales, we treat them as a single collective here given that, on the whole, and with the exception of certain residual teaching categories, they constitute successive potential stages in a single promotion process that is part of a professional academic career. Thus, for example, the category of assistant professor implies the beginning of a professional career that potentially culminates in the position of full professor. It is potential because, in fact, only 15.3 % of full time faculty reach that highest category (70.3 % being men and 29.7 % women) according to the data extracted from the University of Valencia personnel data. The full time faculty constitutes 2508 people, 56 % of whom are men. The average age of this collective is 52 years of age, women being younger with an average age of 50.7 (see Table 2).

Attached faculty refers to the personnel that carries out teaching and research tasks, as do full-time faculty, but, also provides health care services in University Hospitals. For the work they carry out in hospitals they receive a specific salary supplement under the label “attached staff”. Thanks to this supplement their total remuneration is doubled. For both these reasons (differences in the content of the job and double remuneration), persons hired under these conditions are placed in a specific collective.

Attached faculty constitute a small minority of 98 persons, overwhelmingly male (81 % of its members are men). The average age of this collective is the highest among all faculty at 61.4 years of age. In the case of women in this position, the average age is 58.7 years of age (see Table 2).

The formulas used to calculate the GPG

The operative definition of the gender pay gap is the following: “The GPG is the percentage difference between the average gross annual salary of women compared to the average gross annual salary of men”.

For the calculation of the GPG, all UV payroll income received during 2021 was included: base salary, salary complements of all types and benefits received. Therefore, the analysis presented refers to the salary gap and not the income gap, since data is not available on the possible additional economic income that full time faculty may receive beyond the information reflected in their pay slips. The calculation of the GPG is based on the computation of days worked throughout the year and homogenizes them using a coefficient.

Two calculations are applied, average annual compensation (AAC) and median annual compensation (MAC). Ultimately, to obtain both the AAC and the MAC, all the payroll components produced during the year 2021 were included in the calculation for each record (or, in other words, for each worker), regardless of whether they are fixed or variable, adjusted by a time coefficient (days worked in the year).

GPG based on average salary is calculated using the following formula:

The GPG based on median salary is calculated applying a similar formula:

When the result of these formulas is zero (0), it means that there is not GPG. When the result is negative (-), it means there is a GPG, in other words, women earn less. If the result is positive (+), it means that women’s wages are higher than men’s wages.

Presence and increase over time of the overall GPG

Table 3 shows the results obtained from the calculation of the overall GPG for the three distinct faculty groups considered in the UV, based on both average and median salary.

The group with the largest GPG is the full time faculty, followed by the attached faculty. The smallest gap is found among the adjunct faculty, mainly because this group is the most homogenous (a single employment category) and the internal differentiation caused by complements is also reduced, which limits the possibilities that produce a gender gap. In the case of full time and attached faculty the closeness of the average and median values indicates that the results obtained for the GPG are very representative.

Among full time faculty, women earn on average 12.8 % less than their male counterparts, which means that their average annual income is 6815 € less than their male counterparts. According to the median, the GPG provides similar data, with a gap of 11.6 %, which represents an annual income of 7621 euros lower than that of their male peers.

The results obtained for this group can be compared longitudinally, as the 2017 study at the UV, using 2015 data (Díaz, Jabbaz and Samper, 2017) included this same group as one of the units of analysis. When comparing the GPG of full time faculty taking into account the 2015 and 2021 data, we find an increase in the overall GPG of almost 2 % (from 10.97 % in 2015 to 12.8 % in 2021).

Therefore, despite the efforts made by the university’s Equality Unit, the GPG has not only continued, but has worsened, demonstrating the deep-rooted nature of the dynamics that generate inequality. It is possible that the COVID-19 pandemic may have had an impact on the GPG.

The attached faculty are the collective with the second highest GPG. The few women that are part of this group (19 women) earn, annually and on average, a salary 11.8 % lower than that of men. This translates to 12 462 € less income annually. Lastly, among adjunct faculty we find a 7.1 % gap. In other words, women earn annually and on average 402 € less than their male counterparts for their work at the UV.

In the latter case, the euro value of the gap increases when the median is calculated, standing at 11 %, which represents a difference of 537 € less per year for women adjuncts in comparison to men. The pronounced difference between the gap calculated by the average (7.1 %) and by the median (11 %) is because adjunct faculty participate in differentiated teaching regimes and the data collection when calculating the median fell between two regimes, which increased the gap.

Lastly, to finish the analysis of the global GPG, we compare our results with those obtained by the statewide study of Martínez Tola et al. (2023). That study found that the UV had a of global GPG of 21.7 % (p. 43), a value far above the global GPG observed in our study for each of the collectives analysed at the UV (Full-time: 12.8 %; Adjunct: 11.8 % and Attached: 7.1 %). They locate the UV among the 4 universities with the highest GPG in Spain.

According to our analysis, this is due to a grouping error given that, as we said, this measure is the total for teaching and research faculty, without controlling for the impact of the extremely high salaries of attached faculty, who are overwhelmingly male. By considering the three groups of faculty together, the gap calculated is, in reality, a reflection of the salary differences among categories of faculty.

In the Martínez Tola et al. (2023) study the measurement of the GPG was adjusted by a coefficient that involved considering all persons who formed the basis of the calculation to be in a fictitious situation, as if they were all working full time. This measure of the GPG reduces the GPG, placing it at 17.6 %. The gaps of other universities are also modified, although in different proportions, reflecting their hiring structures.

In short, while the overall GPG is data from a specific period of time, it reflects both past and present indirect discrimination produced throughout individuals’ trajectories. For this reason, it is important to clearly determine what we want to measure.

In what follows, GPG data is presented specifically for the group of full time faculty and the specific category of Tenured University Lecturer [Titular de Universidad], given that, for reasons of space, we cannot present all our results.

Age has a direct relationship with academic trajectories, which in turn are marked by gender. This is clearly reflected in the GPG (see Table 4).

Table 4. Overall GPG for Full Time Faculty, by age range

|

Age range |

Number |

GPG |

|

|

Women |

Men |

||

|

Up to 40 years of age |

182 |

172 |

-10.4 % |

|

41 to 50 |

313 |

298 |

-8.6 % |

|

51 to 60 |

425 |

573 |

-8.9 % |

|

61 and above |

188 |

357 |

-4.2 % |

|

Total |

1108 |

1400 |

-12.8 % |

Source: By authors based on data from Jabbaz (2023).

This table shows the GPG for all the age groups. The largest gap is found in the age group of those 40 years of age and under, which is directly related to this being the age when parenthood is commonly initiated. The burden of care, still feminized, on women, implies a more limited possibility of dedication to academic production, which is reflected in the pay gap.

The gap decreases significantly in the last age group. There is still a GPG, but what is observed in this cohort is, above all, a gap in the presence of women, as approximately one-third of the total faculty in this cohort are women.

The impact of salary components

In this section we look at the impact of the components of salary on the GPG, in other words, direct wage discrimination based on the differing participation of women and men in the work opportunities that impact remuneration. The gap is, therefore, reproduced daily.

There are two procedures: the measurement of the GPG for each component (which can be seen in Table 5 in the row “GPG %”). And the measurement of the contribution of each salary component to the GPG for total remuneration (last column). To calculate this, it was necessary to consider the dissimilar weight of each component in total remuneration. Thus, we calculated the gap in absolute terms (seen in the row “GPG €”) and then, the impact of each component on the GPG for total remuneration8.9

For reasons of space, in this article we only include the analysis of the salary components in the case of Tenured University Lecturers (now onwards, TU). We chose this category because it is largest employment category, constituting 595 men and 483 women; it is also the employment position in which persons tend to remain the longest.

In Table 5, a 3 % GPG is observed for total remuneration among TU, which represents a figure somewhat below that found for the year 2015 when it reached 4 % (Díaz, Jabbaz and Samper, 2017; Jabbaz et al., 2019). The current gap means that, on average, women in this employment category earn 1572 € less per year than their male counterparts.

The main source of the GPG is the “research” for which faculty are paid, with a GPG of -70 % with an impact of 101 % on the total pay gap. “Education” referring to the delivery of courses and seminars also stands out, with a GPG of -14 % which explains 9 % of the total pay gap.

The research for which faculty are paid usually has two sources, contracted research and European funded research10. In the first case, the funding is not competitive but is based on direct contracting by public or private agents. Access to the funding depends on social capital or the network of contacts that the researchers have and, perhaps, on their negotiating capacity at the interface between the university, other entities and the market.

Regarding European funded projects, access is competitive, but there is indirect gender discrimination, as the glass ceiling in academic careers conditions access to positions of lead or principal researcher, as well as affecting balanced integration in research teams.

What appears as “teaching” in Table 5 refers to courses and seminars taught by the faculty. Although its impact on the GPG is not great, it is worthwhile to reflect on. This is income that the faculty manages itself, independently of the formal teaching included in the academic contract and therefore in regular remuneration. In this case, women’s double or triple working day, their limited time availability, is probably the deciding factor that generates a gap in this item. And one that is sustained over time.

It is striking that, on the one hand, there is a GPG for three-year period complements11 (-4 %) with a contribution to the pay gap of 12 %. But, on the other hand, there is a moderation of the GPG of 15 % thanks to the five-year period complements12.

The “regional complement” has a reduced impact on the GPG on remuneration, of 6 % (-86 € annually). This complement is transferred from the Valencian regional government (Generalitat Valenciana) to full time faculty and is related to academic administration and participation in international scientific networks. Regarding the gap generated by these items, 2 % could be attributed to coordination and 1 % to management tasks13.

Laura Blanco presents five reasons for which women in academia receive, on average, lower remuneration than men. They are: 1) The existence of vertical segregation in the academic hierarchy that tends to place women in the lower categories; 2) Women’s lower productivity in research in comparison to men; 3 )The existence of higher publication costs for women; 4) Less recognition for the work done by women academics relative to that received by men, indicated by fewer citations, less access to networks, higher non-productive workloads that slow down and interrupt research and lower ratings in their teaching evaluations; and 5 )the existence of biases against women or in favour of men on the part of evaluation committees (2023: 1).

We agree with the factors presented by Blanco, but we must make a caveat: among the tenured professors at the University of Valencia, scientific productivity among women is not lower (six-year complement14), but there is lower participation in paid research. However, this result is due to only one employment category being considered here. However, if we consider all full-time professors (taking into account that it is among Full Professors or Chairs where these six-year complements are concentrated, and that these positions are male-dominated), then there is a higher proportion of men receiving these six-year period complements.

All of these results for the TU can be observed clearly in the Graph 1.

Women tenured university lecturers have better performance in regard to the sexennial complement (2 %), although this only moderates the total gap by 4 %. The higher quantity for sexennials of women in this category can be explained by the fact that for many of them the position they hold is their last one (they will not be promoted to chair of full professorship) and, therefore, they remain longer in their position as tenured university professor than their male colleagues.

Lastly, we have grouped under “others”, payments for authors’ rights, collaboration and assistance at entrance exams, vacations not taken, bonuses for extraordinary services, compensation for termination of contract and contribution to the Pension Plan. Some of these items correspond only to the Administrative and Service Personnel.

The aim of this article is to contribute to the conceptualization and measurement of the gender pay gap to provide an approach that can be consistently used in different organizations and geographic regions.

In this regard, we find that the GPG has two dimensions. One of these is the direct GPG, linked to daily practices and rooted in access to employment opportunities, which continues to reproduce gender inequalities. The other dimension is the less visible indirect GPG, rooted in inherited structures, and which produces slower employment trajectories for women and with greater obstacles.

Another contribution this article makes is the methodological approach to identifying homogenous units of analysis within organizations (fields/collectives), before proceeding to measure an overall GPG, so that the result is coherent and consistent.

In addition, in our analysis of salary components, we measure not only the gap in each component, but also their contribution to the total GPG.

The results obtained in our case study of the UV show the existence of a GPG that has persisted over time and has been increasing in its magnitude. The salary complements regarding “research” and “courses and seminars” are the two items that were identified in 201715 as sources of the GPG in the UV and again stand out as such in this second study of the GPG at the UV.

It is not surprising that these two components stand out as factors generating the direct GPG as they are the least regulated in Spanish universities. As noted, we spoke before of discretionary cracks (Jabbaz et al., 2019), referring to those unregulated spaces within university bureaucracies that do not favour women because it is in such spaces where discretionary gender related power, generally invisible, seeps in.

In some cases, these spaces are difficult to regulate because the decision-making power lies outside the university, such as, for example, with the entities contracting research. However, the universities can also establish regulations that have an impact in such contexts, for example, promoting gender balance in the composition of participating research teams. As is mentioned in the introduction, the promotion of equality through the inclusion of a gender perspective in university regulations is a requirement that we are increasingly finding in Spanish universities.

These results reveal the need to reverse the situation and the urgency of rethinking the academic model of academic careers that fosters these inequalities. Affirmative actions taken in the universities (Alcañiz, 2023; Jabbaz et al., 2023) have the aim of modifying the opportunity structure, addressing the differing material conditions of men and women, to achieve substantive equality in their conditions as university employees.

Men’s trajectories tend to go in a straight line, while women’s trajectories have to overcome what in academia are considered as obstacles to a scientific career (such as, having a child), or sexist stereotypes, prejudice and other forms of discrimination that limit their opportunities. As a result, women’s careers are often more circuitous.

Some of these obstacles are located in the present and others in the past, but they all shape employment trajectories and have an impact on the wage gap, and they accumulate as well.

The GPG is a synthetic indicator of inequality that reflects the effects of the different trajectories that women and men have in academia. Because of this, to eradicate this inequality, the focus must be placed on comprehensive equality policies, including formal and informal aspects, in the classroom, in research, in management, in the transfer and application of knowledge to other spheres and in the internationalization of science and the dissemination of knowledge, in other words, in all areas and issues. Gender studies in general and the GPG in particular, are, little by little, revealing the situations that need to be corrected in order to make universities spaces of knowledge production that value all humans’ capacities and creativity, generating greater equity in academic trajectories, so that the diverse routes are not penalised, incorporating obstacles as parts of life and changing our culture long term.

Acker, Joan (1992). “From Sex Roles to Gendered Institutions”. Contemporary sociology, 21(5): 565-569. doi: 10.2307/2075528

Acosta Revelles, Irma L. (2021). “Científicas a la sombra, también en el espacio virtual”. Asparkía, 38: 59-82. doi: 10.6035/Asparkia.2021.38.4

Alcañiz Moscardó, Mercedes (2023). De la emancipación a la regulación. La Ley 3/2007 de Igualdad desde la perspectiva sociológica y de género. In: I. Pastor Gosálbez (ed.). Una ley para la igualdad: Avances y desafíos 15 años después de la aprobación de la LO 3/2007 (pp.11-24). Tarragona: Universitat Rovira i Virgili.

Arcos Vargas, Marycruz (2022). La no discriminación en el derecho derivado de la Unión Europea. In: J. M. Morales Ortega (eds.). Realidad social y discriminación: estudios sobre diversidad e inclusión laboral (pp.17-41). Murcia: Laborum.

Babock, Linda; Recalde, María; Vesterlund, Lise and Weingart, Laurie (2017). “Gender Differences in Accepting and Receiving Requests for Tasks with Low Promotability”. American Economic Review, 107(3): 714-747.

Becker, Gary S. (1993) [1964]. Human Capital. A theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Blanco, Laura (2023). “Engañadas por la academia: Una revisión del estatus de las mujeres en la academia”. Revista de Ciencias Económicas 41(1): 1-28.

Bourdieu, Pierre (1990) [1984]. Algunas propiedades de los campos. In: Sociología y Cultura (pp. 52-65). México: Grijalbo.

Connell, Robert W. (1996). “New Directions in Gender Theory, Masculinity Research, and Gender Politics”. Ethnos, 61(3-4): 157-176.

Díaz, Capitolina; Jabbaz, Marcela and Samper, Teresa (2017). Estudio sobre brecha salarial de género en la Universitat de València. Available at: https://www.uv.es/igualtat/webnova2014/Brecha_salarial_UV.pdf, access April 1, 2024.

Drolet, Marie and Mumford, Karen (2012). “The Gender Pay Gap for Private-Sector Employees in Canada and Britain”. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 50(3): 529-553.

Freixes Sanjuán, Teresa (2008). La Configuració de la igualtat entre les dones i els homes. In: E. Bodelón and P. Gimenez (eds.). Construint els drets de les dones: dels conceptes a les polítiques locals (pp. 167-184). Barcelona: Diputación de Barcelona.

Frieze, Irene H.; Olson, Josephine E.; Murrell, Audrey J. and Selvan, Mano S. (2006). “Work Values and their Effect on Work Behavior and Work Outcomes in Female and Male Managers”. Sex Roles, 54: 83-93.

Jabbaz Churba, Marcela (2023). Brecha salarial/2021 en la Universitat de València. Available at: https://www.uv.es/igualtat/webnova2014/INFORME_BSG.pdf, access April 1, 2024.

Jabbaz, Marcela; Samper-Gras, Teresa and Díaz, Capitolina (2019). “La brecha salarial de género en las instituciones científicas. Estudio de caso”. Convergencia, 80: 1-23. doi: 10.29101/crcs.v26i80.10418

Jabbaz Churba, Marcela; Soler Julve, Inés; Gil Junquero, Mónica and Belando Garín, Beatriz (2023). Informes d’impacte de gènere en la normativa universitària: guia de recomanacions i bones pràctiques en les universitats de la Xarxa Vives Xarxa Vives. Castellón: Xarxa Vives y Universitat Jaume I.

Jubeto Ruiz, Yolanda and Larrañaga Sarriegi, Mertxe (2016). Presupuestos con enfoque de género (PEG) en la UPV/EHU: Análisis del Capítulo I, año 2013. Leioa-Erandio: Universidad del País Vasco. Dirección para la igualdad.

Martín Bardera, Sara (2018). “Querer y poder: (Des)igualdad en la universidad pública española”. Contextos educativos: Revista de educación, 21: 11-34. doi: http://doi.org/10.18172/con3304

Martínez Tola, Elena; Cal Barredo, Mari Luz de la; Etxezarreta Etxarri, Aitziber and Galbete Jiménez, Arkaitz (2023). Estudio Brecha salarial de género en las universidades públicas españolas. Universidad del País Vasco, CRUE, ANECA y Ministerio de Universidades. Available at: https://www.universidades.gob.es/estudio-brecha-salarial-de-genero-2023/, access April 1, 2024.

Massó Lago, Matilde; Golias Perez, Montserrat and Nogueira Martínez, Julia (2022). Brecha salarial de género en las universidades públicas españolas (informe final). CRUE, ANECA y Ministerio de Universidades de España. Available at: https://www.crue.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/INFORME_BRECHA_SALARIAL.pdf, access April 1, 2024.

Oaxaca, Ronald (1973). “Male-female Wage Differentials in Urban Labor Markets”. International Economic Review, 14(3): 693-709.

Sánchez Vidal, María Eugenia (2016). La brecha salarial desde la perspectiva de la Dirección de Recursos Humanos, estudio de las causas y posibles soluciones. In: C. Díaz and C. Simó (eds.). Brecha salarial y brecha de cuidados. València: Tirant Humanidades.

Simó Noguera, Carles X.; Mondragón García, Elvira; Carbonell Asins, Juan and Romero Crespo, Juan (2023). “La observación de la brecha salarial de género ajustada. En busca de la discriminación directa en España”. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 81(3): e233.

1 This study was supported and financed by the University of Valencia within a programme of research launched under the Vice-rector for Equality, Diversity and Inclusive Policies, and the University’s Equality Unit, to obtain rigorous knowledge to ground university policy from a gender perspective.

2 The first study at the University of Valencia was carried out using data from 2015 (Díaz, Jabbaz and Samper, 2017; Jabbaz, Samper and Díaz, 2019). Prior, there was a study on Presupuestos con enfoque de género/2013 at the University of the Basque Country, which included an analysis of the GPG (Jubeto and Larrañaga, 2016) and, after, under the support of the Ministry of Universitites, these pioneering studies were extended to all Spanish universities (Massó et al., 2021; Martínez Tola et al., 2023).

3 We refer to “discretionary cracks” in a bureaucratic organisation such as the university, as those opportunities or spaces that are unregulated by norms and on which influence or discretionary decision-making power can be exercised.

4 In short, the sample for the Wage structure survey is based on two-stage sampling, selecting establishments and workers through random stratified sampling, including 18 autonomous regions, branches of activity defined by the CNAE-09 classification, and considering the size of establishments as measured by the number of workers. Available at: https://www.ine.es/metodologia/t22/meto_ees18.pdf

5 See our publication on best practices and positive actions taken in the Vives Network of Universities (Jabbaz et al., 2023).

6 The 2015 data come from our earlier study of the GPG at the University of Valencia: Díaz, Jabbaz and Samper, 2017).

7 The year of reference for the study is 2021 and, therefore, the definition of the employment categories (to which the base salary is associated) and the forms of access to employment and promotion, are subject to what is established in Organic Law 6/2001 of 21 December regarding the Universities, and its posterior modifications.

8 The calculation of the “impact” of each component is based on the following formula: component in € / total remuneration in € x 100. We must point out that when the sign is negative, this means that it moderates (reduces) the GPG for total remuneration. When the result is positive, this means that impact strengthens (increases) the GPG (see the last row of Table 5).

9 It should be noted that it is not completely accurate to refer to a GPG in the case of base salary, destination complement and specific complement, whose values depends on the employment category and are established by means of a Resolution of the General State Administration. The Destination and Specific components are variables that are in other cases determined by other public administrations (Municipal and Regional, as well as the State, in which they remunerate the level of the employment position and responsibility, respectively). But in our case, the universities, they are fixed components based on employment category and, therefore, there should be no GPG. In the table, however, we see small differences (of 1 % in the case of base salary and in the Specific complement) linked to the effects on these components produced by other Social Security benefits (leaves and other absences).

10 There are many competitive R&D projects that do not pay researchers, only paying the costs of research.

11 Every three years the three-year complement is recognized. However, if prior to employment in the university in a category such as that of tenured university lecturer, a faculty member worked in a public administration, the years so employed are recognized and validated, being added to those acquired subsequently in the university.

12 The five-year supplements are granted every 5 years. However, they are not automatic but are based on an evaluation of the quality of faculty teaching using several indicators: self-evaluation, surveys of student satisfaction, teacher training, participation in projects related to educational innovation, development of teaching materials and recognition of academic management.

13 The item in the table referring to coordination refers to coordinating positions of intermediate level, for example, coordinating a degree programme. While management refers to a higher level related to the management of centres (faculties, departments and institutes) or within the university rectorate.

14 The six-year complements for productivity regarding research activity are based on evaluations that the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation -ANECA – carries out. Faculty can submit up to 5 publications of sufficient quality covering a period of 6 or more consecutive years for positive assessment and eligibility for the complement. Therefore, this is not an indicator that correlates with seniority, as does the three-year complement (seniority in administration) and the five-year complement (seniority in university teaching).

15 (Díaz, Jabbaz and Samper, 2017). In this study, data from 2015 was used.

Table 1. Typology, unit of analysis, measurement level and characterisation of the GPG

|

Type |

Unit of analysis |

Measurement level |

Characterization |

|

Direct GPG |

Categories (fixed and variable wages) |

Adjusted |

Functional and reproduced daily |

|

Indirect GPG |

Trajectories (in each field/group) |

Unadjusted/Overall |

Structural, inherited |

Source: By authors.

TablE 2. Sociodemographic characteristics of University faculty

|

University Faculty |

Sex |

Frequency |

Average age |

|

|

(N) |

(%) |

|||

|

Adjunct faculty |

Men |

926 |

50 |

50 |

|

Women |

926 |

50 |

47.5 |

|

|

Total |

1852 |

100 |

48.7 |

|

|

Full time faculty |

Men |

1.400 |

56 |

53.3 |

|

Women |

1.108 |

44 |

50.7 |

|

|

Total |

2.508 |

100 |

52.2 |

|

|

Attached faculty |

Men |

79 |

81 |

62.1 |

|

Women |

19 |

19 |

58.7 |

|

|

Total |

98 |

100 |

61.4 |

|

|

TOTAL |

4.458 |

- |

54.1 |

|

Source: By authors based on data from Jabbaz (2023).

AAC for women – AAC for men

AAC for men

X 100 = GPG according to average salary

MAC for women – MAC for men

MAC for men

X 100 = GPG according to median salary

Table 3. Overall GPG for all teaching and research staff by average and median salary (percentages and annual)

|

All teaching and research faculty |

Frequency (N) disaggregated by sex |

GPG average |

GPG median |

||

|

% |

€ annual |

% |

€ annual |

||

|

Adjunct |

Men: 926 |

-7.1 |

-401.63 |

-11.00 |

-536.98 |

|

Women: 926 |

|||||

|

Full time |

Men: 1400 |

-12.8 |

-6,815.24 |

-11.60 |

-7,621.10 |

|

Women: 1108 |

|||||

|

Attached |

Men: 79 |

-11.8 |

-12,462.01 |

-12.00 |

-12,480.49 |

|

Women:19 |

|||||

Source: By authors based on data from Jabbaz (2023).

Table 5. Tenured University Lecturers: GPG by components/complements and their impact on average total remuneration (% and € earned annually)

|

Sex |

Base Salary8 |

Destination compl. |

Specific compl. |

Three-year period compl. |

Five-year period compl. |

Six-year period compl. |

Regional Compl. |

Research |

Teaching |

Benefits |

Management |

Coordination |

Patents |

Others |

Rem. Total |

|

Men |

15,857 |

12,026 |

6,621 |

4,871 |

7,342 |

3,496 |

2,143 |

2,268 |

1,004 |

120 |

837 |

226 |

24 |

270 |

57,106 |

|

Women |

15,990 |

12,076 |

6,700 |

4,686 |

7,577 |

3,561 |

2,057 |

687 |

865 |

88 |

816 |

198 |

27 |

207 |

55,534 |

|

Total |

15,917 |

12,049 |

6,656 |

4,788 |

7,447 |

3525 |

2,105 |

1,560 |

942 |

105 |

828 |

214 |

26 |

242 |

56,402 |

|

GPG % |

1 % |

0 % |

1 % |

-4 % |

3 % |

2% |

-4 % |

-70 % |

-14 % |

-27 % |

-3 % |

-13 % |

14 % |

-23 % |

-3 % |

|

GPG € |

133 € |

50 € |

79 € |

-185 € |

235 € |

65 € |

-86 € |

-1,581 € |

-138 € |

-32 € |

-22 € |

-29 € |

3 € |

-63 € |

-1,572 € |

|

Impact |

-9 % |

-3 % |

-5 % |

12 % |

-15 % |

-4 % |

6 % |

101 % |

9 % |

2 % |

1 % |

2 % |

0 % |

4 % |

100 % |

Source: By authors based on data from Jabbaz (2023).

Graph 1. Contribution of salary complements to the gender wage gap among tenured professors

Source: By authors based on data from Jabbaz (2023).

RECEPTION: March 05, 2024

REVIEW: May 27, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: July 10, 2024