doi:10.5477/cis/reis.190.63-88

Equal and Non-transferable Entitlement? Preferences Regarding the Parental Leave System in Spain

¿Iguales e intransferibles? Preferencias por el sistema

de permisos por nacimiento

Julia Cañero Ruiz and Danislava Marinova

|

Key words Maternity Leave

|

Abstract Given the lack of research on preferences regarding the parental leave system in Spain, this study uses data from an original survey of 3100 new mothers and fathers to show that acceptance levels of the current equal, non-transferable parental leave system are very low (10.4 %), and that there is a considerable gender gap in preferences on the distribution of parental leave. In contrast, broad acceptance rates of the creation of new pre- and post-partum leave to protect the mother’s health were found (97 %), even among those who prefer equal duration of parental leave for both parents. Systematic inconsistencies in preferences were also identified, which lead to the conclusion that these preferences are not yet crystallised probably due to the absence of political and social debate on the characteristics and implications of the new parental leave system. |

|

Palabras clave Permiso de maternidad

|

Resumen Ante la ausencia de estudios sobre las preferencias hacia el sistema de permisos por nacimiento en España, la presente investigación, con datos de una encuesta original de 3100 madres y padres recientes, revela una aceptación muy baja (del 10,4 %) del actual sistema de permisos iguales e intransferibles y una brecha de género considerable en las preferencias sobre la distribución de los permisos. En cambio, encontramos amplia aceptación (del 97 %) para la creación de unos nuevos permisos preparto y posparto para proteger la salud de la madre, incluso entre personas que prefieren permisos de igual duración. Además, señalamos incoherencias sistemáticas en las preferencias y deducimos que estas no están cristalizadas, seguramente debido a la ausencia de debate político y social respecto las características y repercusiones del nuevo sistema de permisos por nacimiento. |

Citation

Cañero Ruiz, Julia; Marinova, Danislava (2025). «Equal and Non-transferable Entitlement? Preferences Regarding the Parental Leave System in Spain». Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 190: 63-88. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.190.63-88)

Julia Cañero Ruiz: Universidad de Granada | juliacanero@gmail.com

Danislava Marinova: Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona | dani.marinova@uab.cat

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 190, April - June 2025, pp. 63-88

Maternity leave, in the early days of its existence in Europe, aimed to ensure the health and well-being of both mother and baby (Moss, 2018). Parental leave has recently become an instrument for work-family balance and for gender equality, especially in the last few years (Meil, Rogero-García and Romero-Balsas, 2020). Spain’s current parental leave system is grounded in principles of equality and non-transferability, as part of gender equality policies. This approach is designed to promote joint responsibility in early childhood care, encourage men’s socialisation as careers and foster a fairer distribution of unpaid work (Meil and Escobedo, 2018). The objective of equality has taken precedence over others, such as work-life balance, maternal health and child welfare. Royal Decree Law 6/2019, on urgent measures to guarantee equal treatment and opportunities between women and men in employment and occupation, significantly changed the meaning of these benefits1. They are also no longer explicitly aimed at the protection of women’s sexual and reproductive processes (such as childbirth, postpartum, breastfeeding and postnatal period) or of infants’ needs (exterogestation), but at men’s joint responsibility for care and equality in the labour market.

The reform of parental leave policies in Spain can be seen as a social experiment due to its exceptionality in comparative terms, the speed of its implementation and the drastic difference compared with the gradual evolution of paternity leave until 2017. Paternity leave is comparatively exceptional because of its high reimbursement rate (100%), its long duration (16 weeks) and its non-transferability. European countries with extensive leave do not have such extensive and 100 % paid non-transferable leave for fathers (Merino, 2017; Blum et al., 2023). However, the 16-week leave available to mothers is comparatively low and has a gap of thirty-eight paid weeks than the European average (Escobedo, 2022)2. No other EU country has opted for making parental leave a non-transferable, equal, individual entitlement (Meil, Rogero-García and Romero-Balsas, 2020).

The European trend towards parental joint responsibility for childcare was reflected in Directive 2019/1158 of the European Parliament and of the Council, which for the first time, recognised a two-week paternity leave and a four-month parental leave (a two-month paid, non-transferable leave for each parent) to promote equal sharing of care tasks within the couple. The 1992 Directive, which is still in force, provides for a minimum of 14 weeks paid maternity leave. Combining the two Directives, mothers should have at least 22 weeks’ paid leave and fathers should have at least 10 weeks’ paid leave. These entitlements are not applied in current Spanish legislation.

In addition to the exceptional nature of equal and non-transferable leave in comparative terms, it is a break from the gradual evolution of paternity leave in Spain until 2017. Spanish fathers only had a 2-day leave until 2007 and a 2-week leave between 2007 and 2017. From 2017 onwards, paternity leave increased dramatically, to the extent that it became sixteen weeks long in 2021, a 700 % change. When this rapid expansion is considered in addition to the change in the raison d’être for parental leave (from protecting the mother’s and newborn’s health to promoting joint responsibility and equality in the labour market), equal, non-transferable leave is historically a new model. In light of the speed of these changes, there is a need to study the degree of acceptance of the new parental leave system by new mothers and fathers.

The political context of the reform: lack of debate and political opposition

The political context of the parental leave reform and the positions of the main political actors may be relevant for understanding the preferences held about the current leave system. As Meil et al. (2022) pointed out, the shift that caused parental leave entitlement to be equal between men and women took place in an exceptional political context: there was little social debate, prior studies or political opposition. The social debate since then has taken place outside the institutions and largely emerged after the approval of Royal Decree Law 6/2019. This section reviews the main social actors that have driven the reform or taken a position on the issue.

The fertility survey conducted by the National Institute of Statistics in 2018, a year before the Royal Decree Law was passed, is a good indicator of public opinion about parental leave: almost 81 % of women aged eighteen to fifty-five called for it to be extended, compared to 19 % who called for its being made equal for mothers and fathers. Among men aged 18 to 55, almost 69 % stated that it should be extended, compared to 31 % who expressed their preference for equal maternity and paternity leave. The increase in the length of leave is the main incentive demanded by women to have children, well above other incentives such as nursery schools (INE, 2018). Based on these data, one year before the Royal Decree Law was passed, there was no social demand for parental leave entitlement to be equal for mothers and fathers, and the vast majority of women and men prioritised the extension of maternity leave.

The preference for the extension of maternity leave included mothers’ and professionals’ groups3 demands; however, their preference went unheeded, as a reform was quickly developed without political or trade union opposition. The measure came from left-wing parties, but there was no alternative proposal from conservative parties, not even the extreme right-wing party Vox opposed it (Meil et al., 2022). In fact, Convergència i Unió (CiU), a conservative party, put forward a bill based on this leave model in 2012. In May 2018, Unidos Podemos launched a bill, also supported by all groups. Just eight months later, in March 2019, the Royal Decree Law came into force while there was a coalition government of the PSOE and Unidos Podemos. While in opposition, the Partido Popular lodged an appeal against the fact that this measure was processed through the urgency procedure, but not against the measure itself. Ultimately, this highlights the speed with which the reform was processed and the absence of debate and alternative proposals from the opposition parties.

This consensus contrasts with the intense debates held in other countries that reformed parental leave entitlement. In the 2020 reform in Iceland, there were some arguments that advocated a higher quota for fathers with the aim of encouraging their involvement in childcare and decreasing discrimination against women in the labour market; on the other hand, there were other arguments that emphasised the appropriateness of breastfeeding until an infant is twelve months old, the risk of losing unused leave time allocated to fathers, discrimination against single-parent families, freedom of family choice, maternal attachment and the extension of maternity leave to two years (Arnalds, Eydal and Gíslason, 2022). The lack of a similar debate in Spain is surprising, given that making paternity leave equal to maternity leave has led to a significant increase in public spending on men (Escobedo, 2022). This increase, however, has been offset by a significant drop in the birth rate, which has not improved after the parental leave reform.

Among the main non-institutional political actors that drove the current legislation was the Platform for Equal and Non-transferable Birth and Adoption Leave (PPiiNa), an association that was born in 2005. In 2011, eight years before the implementation of the Royal Decree Law, a sub-committee was created within the Equality Commission to address parental leave entitlement and the need to make maternity and paternity leave equal, thus partially adhering to the proposal made by the PPiiNa (Meil et al., 2022). The current parental leave system is almost identical to the original PPiiNa demand, except for the number of compulsory weeks after childbirth. Currently, they are calling for a reduction of this period (from six to two weeks), so that fathers can look after infants on their own for longer —not simultaneously with mothers—. The central arguments made by the platform have been that making maternity and paternity leave equal by increasing non-transferable paternity leave would increase joint responsibility of men in childcare, as well as decrease the labour discrimination experienced by women. For this platform, it was essential for the extension to be 100 % paid as an economic incentive for fathers to use the leave, a measure that was finally maintained.

On the other hand, mothers’ groups, breastfeeding groups and health professionals called for the extension of the minimum maternity leave to six months (exclusive breastfeeding period), but there was no group that made an alternative policy proposal to the model proposed by PPiiNa. In 2018, a group of mothers formed PETRA Maternidades Feministas, a state-wide association that took a stand against the Bill and, subsequently, against the Royal Decree Law. This association argued that the current leave model has not been the result of a social demand, as was the case with the extension of the maternity leave. Furthermore, PETRA held the view that the new legislation failed to consider infants’ needs and mothers’ sexual and reproductive processes, such as pregnancy, childbirth, postpartum, breastfeeding and postnatal period, as needs and processes that need protection through extended paid leave for mothers. PETRA Maternidades Feministas called for the extension of parental leave and the transferability of most of the weeks, so that it can be adapted to the individual situation of each family. They also called for parental leave to be universal, as access to parental leave is subject to parents being registered as being employed at the time of birth and to minimum periods of contribution to the social security system, which means that a third of mothers and a quarter of fathers do not qualify for parental leave (Farré et al., 2024). Among its many policy proposals, the association has called for a universal childcare allowance; pre-birth leave from the thirty-sixth week of gestation; and postpartum leave, of at least eight weeks after childbirth, separate from the current parental leave, to facilitate recovery from and protection for the processes associated with childbirth.

Although most studies have associated equality and non-transferability of parental leave with the left and with feminism (thus linking the extension of maternity leave to conservative sectors), we cannot ignore that this debate is framed in a historical conflict between the feminism of equality and of difference4. This has given rise to a distinction between women’s liberation through employment and access to the public sphere, and through the recognition of differences. In addition, there has historically been a difficult relationship between feminism and motherhood, which has led some currents to consider motherhood and its processes as the cause of women’s oppression, the maintenance of traditional roles and essentialism (Cañero-Ruiz, 2022). While there is consensus among feminists on the need to address the gender gap in employment and the care crisis, the solutions proposed, mainly in the early childhood stage, have been divergent. Rooted in an institutional form of feminism aligned with the equality movement, Spain’s public policies on work-life balance have focused on outsourcing childcare through free nursery schools for children aged 0–3 and encouraging shared parental responsibility via paid parental leave entitlements. On the other hand, a study that used data from several countries (Gribble et al., 2023) pointed out how these actions, aimed at promoting equality by reducing care for mothers and increasing quotas for fathers, have not taken into account the reproductive and labour rights of mothers, nor the health of children, and therefore may violate women’s human rights. Gribble et al (2023) noted that there is a need to differentiate between non-sexed care (such as domestic chores) and sexed care, more related to early childhood (such as breastfeeding), and argued that the latter cannot be reduced or delegated in the same way. The associations PPiiNa and PETRA Maternidades Feministas embody these differing perspectives: PPiiNa prioritises shared responsibility and gender equality in the labour market, while PETRA Maternidades Feministas places a stronger focus on the rights of the mother–baby dyad, emphasising the need to provide rights and resources for sexed, non-transferable childcare and parenting.

Given the political context —marked by a lack of social debate, prior studies, and political opposition— and the swift enactment of the reform, three hypotheses can be proposed regarding preferences toward the parental leave system and how these have been crystallised. Firstly, the reform neglected the preference for longer leave entitlement for the mother, as reflected in the fertility survey conducted by the National Institute of Statistics in 2018. More recent studies have corroborated these results and have shown that half of men and women consider Spanish paternity leave entitlement to be too long (Fundación Cepaim, 2023). Taken together, these data anticipate that there may be low levels of acceptance of the current system of equal, non-transferable parental leave (H1). In a similar vein, we also postulate that there will be a majority acceptance of an alternative system of pre- and postpartum leave entitlement (H2), which would grant more paid leave time to expectant mothers and fits the preferences observed in the INE and Fundación Cepaim data.

Secondly, the absence of political debate in public institutions, as well as the lack of media coverage described above, means that the public has been unable to contrast arguments for and against the current parental leave system, or compare this system with other alternatives. Unlike in countries, such as Iceland, where an extensive parliamentary debate has taken place prior to the reform of parental leave, the Spanish public is probably unclear about the employment and economic implications of this new parental leave arrangement for families, or has misperceptions about the consequences of the reform. This context leads us to propose a third hypothesis: that preferences regarding the current leave system are weakly formed, with potential inconsistencies across various aspects of the reform, including transferability, equality, and the alternative pre- and post-partum leave structure (H3).

Uses, barriers and preferences regarding parental leave entitlement

The current use of parental leave entitlements and reduction in working hours due to childcare responsibilities will now be examined. Both aspects seek to extend care time and may therefore be indicators of mothers’ and fathers’ preferences regarding the extension of parental leave. Building on previous research, employment and socio-economic barriers to the use of parental leave will also be analysed below, together with attitudinal and ideological factors that might influence preferences regarding the parental leave system.

Firstly, men usually make a residual use of unpaid leave of absence and reduced working hours to engage in childcare. In 2023, unpaid leave of absence for the care of minors leave amounted to 84 % for women and 16 % for men (Seguridad Social, 2024). Also, 45 % of mothers who did not qualify for parental leave took unpaid leave, compared to 6 % of fathers (Fundación Cepaim, 2023). Regarding reduced working hours, 92.5 % of the requests were made by women (INE, 2022). Although the take-up rate of paternity leave has steadily increased, which suggests greater acceptance of non-transferable paternity leave, the take-up rate of maternity leave by fathers before the leave entitlement was made equal (when there was a transferable part) remained below 2 % (Flaquer and Escobedo, 2014), suggesting a low demand for extended paternity leave among men. Despite the low level of use of maternity benefit by fathers, most were willing to use it (Escot et al., 2012).

The shift to gender-equal parental leave has not had an impact on the gender gap regarding leave of absence. In 2021 and 2022, parental leave-taking behaviour remained unchanged, with 14.6 % of mothers using their leave entitlement (15.0 % in 2020), compared to only 1 % of fathers (0.9 % in 2020) (Gorjón and Lizarraga, 2024). Additionally, the total percentage of unpaid leave of absence taken by women increased by 10 % in 2023 (Seguridad Social, 2024). Mothers’ motivations for increasingly requesting unpaid leave often included extending childcare time at home and breastfeeding (Baken, 2022). The maternity leave entitlement in Spain is less than the six months recommended by the AEP, WHO, and UNICEF for exclusive breastfeeding. This is despite the fact that return to work is one of the factors contributing to the abandonment of this practice, due to the lack of public policies such as paid maternity leave (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2023).

Overall, mothers’ continued use of leave, including holidays and other unpaid resources to extend care time at home, suggests that many mothers prefer to extend their stay with their babies and would prioritise the extension of maternity leave over the gender-equal distribution of leave. In contrast, the high rates of paternity leave take-up by Spanish fathers indicate that men are probably more satisfied with the current system of equal leave than women. Our fourth hypothesis foresees the existence of a gender gap with respect to the preference for the equal duration of parental leave (H4)5.

Secondly, employment status and socio-economic status may influence preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave, as previous literature has linked these factors to barriers to their use. In particular, self-employed (male and female) workers are less likely to use leave (Romero-Balsas, 2012), as are employees with temporary contracts or those employed in the private sector (Escot, Fernández-Cornejo and Poza, 2014). Recent evidence has suggested that sectors with a higher concentration of occupations with low education requirements have a shorter average duration of parental leave (Castellanos Serrano et al., 2024; Twamley and Schober, 2019). Escobedo (2022) has argued that a certain degree of transferability in leave would guarantee the necessary flexibility for families to overcome these barriers, and that this would be particularly beneficial for those with greater economic vulnerability or job insecurity. These results have implications for preferences regarding the parental leave system. Specifically, we postulate that mothers and fathers with a lower socio-economic profile or a more vulnerable employment situation will prefer a higher degree of transferability of leave (H5).

Finally, we will analyse the impact of attitudinal and ideological factors on preferences regarding the leave system, given that the existing literature has linked attitudes towards gender roles to the use of paternity leave. In particular, rates of paternity leave use are higher among men who express egalitarian attitudes towards joint responsibility for childcare (Romero-Balsas, 2012; Brandth et al., 2022; Lammi-Taskula, 2008), and the same attitudes also influence the (lower) likelihood that the mother may take full parental leave, in the case of longer and more transferable leave entitlements (McKay and Doucet, 2010). Moreover, given that the Royal Decree was an initiative taken by left-wing parties, in particular Podemos, which identifies itself as feminist, we believe that people who define themselves as left-wing or feminist would be more likely to prefer the current leave system6. Therefore, our final hypothesis is that egalitarian attitudes, left-wing ideology and identification with feminism are associated with greater acceptance of equal, non-transferable leave (H6).

To analyse preferences regarding the parental leave system, we designed a survey that was conducted in October 20227. The total sample consisted of 3100 mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2022, of whom a statewide sample of 2700 participated online through Netquest. Due to the specific nature and restrictions of the sample required for this study, netquest could not guarantee its representativeness through quotas. Previous studies have indicated that online surveys in general, and the Netquest panel in particular, are biased towards university-educated and upper-middle income profiles (Hernández et al., 2021). In order to validly weight the sample and ensure greater representativeness, we simultaneously conducted the same survey with four hundred mothers and fathers from low socio-economic backgrounds. Respondents in this group met the following criteria: a) they did not hold a university degree and b) they lived in a low-income neighbourhood in the Metropolitan Area of Barcelona (MAB). In this case, the interviews were conducted face-to-face in children’s playgrounds located in the MAB8.

To analyse preferences regarding the current leave system, we looked at two key aspects: equality and transferability of leave entitlements. With regard to gender-equal leave, the following question was asked: “Do you think that parental leave should be... ...of equal length for mothers and fathers, as it is at present; ...longer for mothers; ...longer for fathers?”. To identify preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave, we asked the following question: “Do you think that parental leave should be... non-transferable, as it is at present, so that neither the leave, in full or in part, can be transferred to the other parent; ...transferable, so that parents can decide how to divide the total number of weeks of leave between them; or ...mixed, with some weeks reserved for each parent and the rest of the weeks transferable between parents?”

In addition to the transferability and equality of the leave system, we asked respondents about their preferences regarding two additional leave entitlements, as proposed by the association PETRA Maternidades Feministas: a pre-natal leave and a post-natal leave. The questions were: “Regardless of the current childbirth and childcare leave, would you be in favour of paid leave.... 1) ...for health protection during the last four weeks of pregnancy? 2) ...to facilitate recovery during the first eight weeks after childbirth?” Respondents could answer “yes” or “no” to both questions.

Among the explanatory factors, we include a battery of standard questions extracted from the European Social Survey on gender roles in care, where factors such as agreement with parental caring capacity or co-responsibility, among others, stood out. We also asked about attitudes towards feminism: “Regarding feminism, do you consider yourself a person...? Responses ranged from “Very supportive of feminism” to “Very opposed to feminism” on a scale of one to five. Political ideology was measured on a scale from 0, extreme left, to 10, extreme right. In addition, the analyses included variables for gender, age, educational level and income. Finally, the birth year of the youngest child was included. The preferences regarding the parental leave system are analysed below, according to the hypotheses formulated.

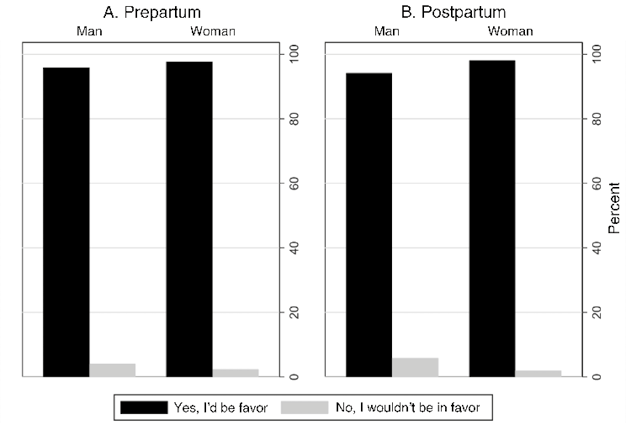

First, a descriptive analysis was conducted about respondents’ attitudes towards parental leave. These were related to preferences as to a gender-equal, transferable leave (H1), the alternative system of pre-partum and post-partum leave (H2), and whether these preferences are strongly or weakly formed (H3). According to the first hypothesis, there is a low level of acceptance of the current leave system, as shown in Table 1: only 10.04 % of the total sample preferred equal and non-transferable leave between parents. Regarding the key aspects of the parental leave system, its non-transferability and equal distribution of weeks, the percentages in Table 1 indicate that 1) transferability, whether in full or in part, was the preferred option for almost 90 % of the sample; and 2) equal distribution of leave was the preferred option for 51 % of the sample, followed by longer leave for the mother, which was favoured by 48.2 % of participants. Table 1 also provides empirical support for the second hypothesis. The alternative proposal by PETRA Maternidades Feministas for pre-partum and post-partum leave for mothers was widely accepted by 97 % of respondents.

To analyse the internal consistency of preferences regarding equality, transferability and the alternative system of pre- and post-partum leave entitlements (H3), the relationship between these preferences in Tables 1 and 2 was examined. Table 1 shows the internal contradictions in preferences regarding the two key aspects of the current leave system: 37.9 % of the total sample preferred having a parental leave of equal duration for both mothers and fathers, but one which is transferable or mixed. However, this was an inconsistency, since introducing transferability would allow for unequal distribution of parental leave entitlement. Table 2 (Column A) shows the rates of acceptance of a new pre-partum leave and agreement with the preference for equal leave. Among those who would support this new specific leave for mothers, only half expressed a consistent preference, i.e. a longer leave for mothers (49.4 %). Half of the sample had contradictory preferences, as they expressed support for both a leave for mothers and gender-equal leave. The contingency table between post-partum leave and equality shows very similar results (see Table 2, column B). These contradictory results suggest that preferences regarding the parental leave system are weakly formed, in line with the third hypothesis.

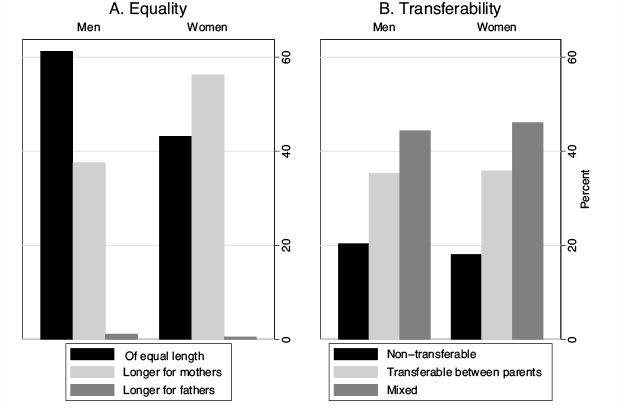

To analyse the gender gap in preferences (H4), Figure 1 shows the distribution of preferences regarding equality and transferability according to sex. As can be seen in Panel A, a significant difference was found between mothers and fathers regarding preferences regarding equal distribution of leave between parents, with the majority of new mothers preferring longer leave for themselves, while the majority of fathers surveyed indicated a preference for leave of equal length. Support for longer parental leave was marginal (<5 % in all cases). Panel B shows that a mixed system (a model that is common in other European countries) was the most preferred type, while the current system of non-transferable leave was the least popular, both among new mothers and new fathers. In short, gender structured preferences regarding the distribution of leave entitlement (equal length or longer for mothers) but not the preference for transferability, which pointed to partial support for the fourth hypothesis.

The descriptive results indicated a wide variation in preferences, which gives grounds to study the effects of socio-economic, occupational and attitudinal factors that determined preferences, in line with the last two hypotheses (H5 and H6). To analyse preferences regarding equal leave distribution, we first fitted logistic regression models on the likelihood of preferring equal leave versus extended leave for mothers9. Table A2 in the Appendix shows the results from three logistic regressions: the first includes socio-demographic factors; the second, attitudinal factors; and the third, both types of explanatory factors that allowed us to compare their impact on preferences regarding parental leave equality. Socio-demographic factors had no explanatory power for preferences regarding equal leave. With respect to gender, mothers were 20 % more likely to prefer longer leave entitlements for themselves (58 % vs. 38 % among men), and this effect held even when socio-economic and attitudinal factors were controlled for, which provided a more robust indication of the gender gap in preferences (H4).

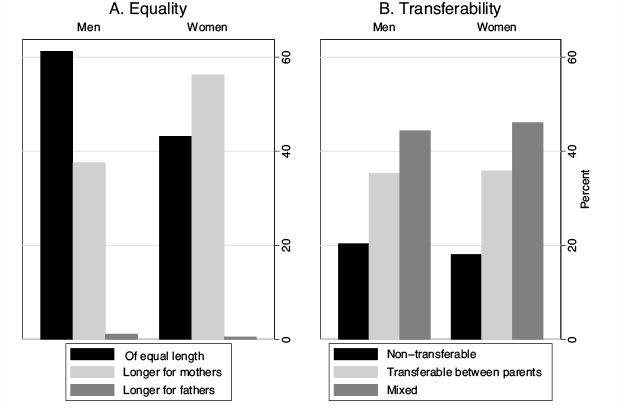

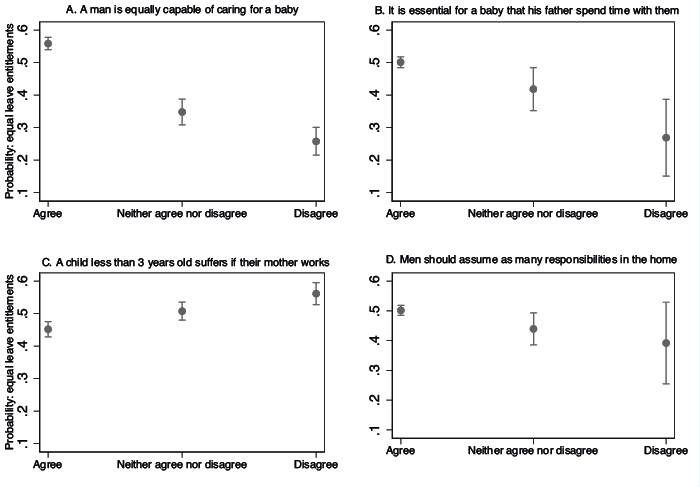

Figure 2 shows the effects of gender attitudes towards parenting on preferences regarding equal parental leave entitlements (effects estimated based on Model 3 in Table A2, controlling for socio-demographic differences, political ideology and attitudes towards feminism). A positive attitude towards men’s caring skills increased the probability of preferring equal leave by 30 % (panel A). Considering it important for fathers to spend time with their babies (Panel B) also raised this probability, although to a lesser degree: 18 % (p<0.05). However, the attitude towards responsibility for childcare shared between men and women (Panel D) had no statistically significant effect on preferences, which contradicts previous studies (Romero-Balsas, 2012; Brandth et al., 2022; Lammi-Taskula, 2008). Educational level had no effect on preferences regarding equal distribution of parental leave either, in contrast with previous studies on the use of equal and non-transferable leave (Castellano Serrano et al., 2024). Furthermore, in line with the third hypothesis, people who expressed agreement with the statement “a younger child suffers if their mother works” had a 40 % probability to advocate for equal length of leave (Panel C). This may be a contradiction, as the current design of equal leave entitlements causes the mother to return to employment early.

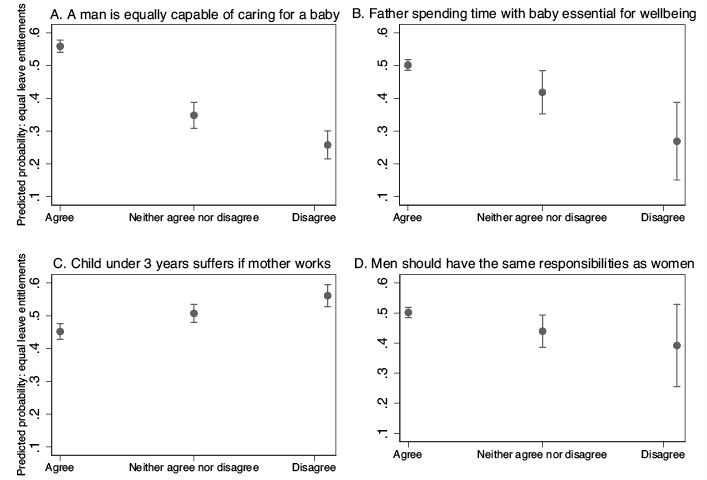

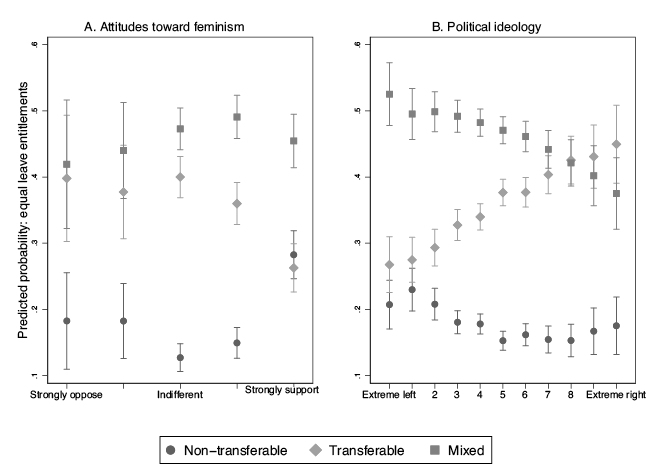

Figure 3 shows the effects of two more attitudinal factors: attitudes towards feminism and political ideology. As seen in Panel A, feminism does not have a clear effect on equality preferences, possibly due to the opposing positions within the different feminist currents around the parental leave system. Panel B shows that the effect of political ideology goes in the expected direction but its magnitude is relatively weak: people who identified with the extreme left had a 0.55 probability of preferring equal leave entitlements; while those who identified with the extreme right had a 0.40 probability (p<0.05). This narrow gap between two such extreme ideological poles may be due to the lack of a clear political opposition by the Spanish right to current parental leave entitlements. Overall, with respect to the equal distribution of parental leave, a statistically significant effect of attitudinal and ideological factors was seen, especially related to gender attitudes and to a lesser extent to ideological positioning (H6). Regarding attitudes towards feminism, hypothesis H6 was not empirically supported.

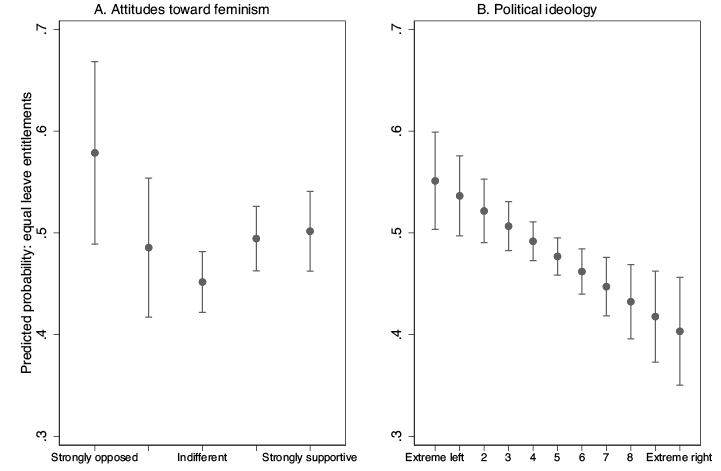

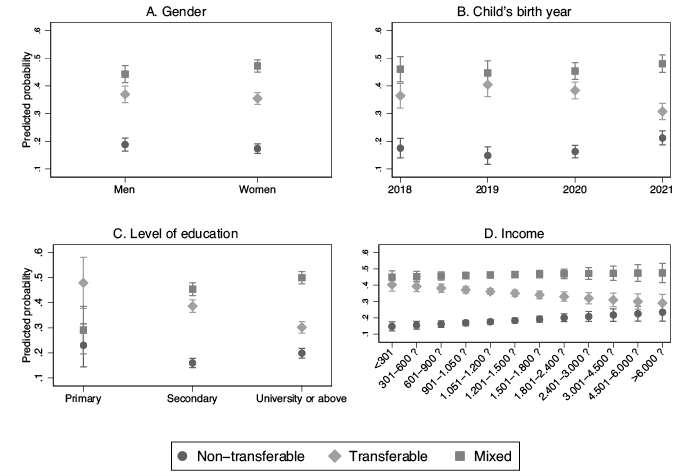

Finally, the preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements using multinomial regressions to model preferences regarding three types of leaves were analysed: non-transferable, transferable or mixed. Table A3 in the Appendix shows the results from three multinomial regressions: the first includes socio-demographic factors; the second, attitudinal factors; and the third, both types of explanatory factors. The different probabilities of preferring each parental leave system are depicted in Figures 5-6. First, we found very low acceptance levels of the current non-transferable parental leave entitlement in Spain (below 20 %), which confirmed the descriptive analyses. The regression results also indicated that there were no groups where this policy was the preferred one. Among mothers and fathers of different socio-economic and ideological profiles, non-transferable leave was the least desired. Instead, mixed parental leave entitlements were the preferred option among all profiles.

In contrast to preferences regarding equal leave, no significant differences for transferability between mothers and fathers were observed (Panel A, Figure 4). In contrast, socio-economic status was found to influence preferences regarding transferability, in line with H5. Mothers and fathers with low incomes and low levels of education expressed a greater preference for mixed leave entitlements, closely followed by fully transferable leave (Panels C and D of Figure 4). As education and purchasing power levels rose, the median preference for non-transferable leave also rose, although it did not exceed 20 % (p<0.05). In contrast, preferences regarding mixed parental leaves did not vary with level of education or income, and remained the most desired option among different socio-economic profiles. Looking at the variation in preferences by year of birth of the child (Panel B), non-transferable leave gained some popularity among parents of children born in 2021 (p<0.05), although preferences regarding mixed parental leave entitlements remained in the majority. This finding suggests that policy changes may have influenced preferences, making the type of parental leave entitlement currently in place somewhat more popular. However, the reform has not changed the preference for mixed leave, which continues to be in the majority and remains stable10.

After providing a literature review, we identified a notable lack of studies on the preferences of mothers and fathers prior to Royal Decree Law 6/2019, which established a non-transferable leave entitlements of equal duration for mothers and fathers. This study provides data on the preferences of new parents after the implementation of the reform. The results reveal a mismatch between current public policies on parental leave entitlements and parental preferences. Only 10.4 % of respondents preferred the system of equal and non-transferable leave, while 89.6 % preferred a different system, with non-transferability being the least desired option. There was a notable gender gap, as mothers tended to prefer a longer leave for themselves, unlike fathers. These results question whether a supposedly feminist policy really meets the needs and preferences of most mothers.

In terms of explanatory factors, it was found that the preference for equality was related to attitudes about fathers’ childcare ability, but not to shared responsibility, which these parental leave entitlements seek to promote. Moreover, political ideology and feminist attitudes did not categorically structure preferences. This result questions the apparent consensus within feminism and the left on the current leave model and reveals that the debate on equality and non-transferability is still open and divergent; a debate that should have taken place before the implementation of the Royal Decree. It also reflects the lack of political opposition, embodied in the preferences of people voting for left and right, respectively.

Our results indicate that families in vulnerable situations request more flexibility through increased transferability of parental leave. This policy could be accompanied by other measures, such as universal leave or paid care leave, which would provide a great deal of financial support to these families. However, there is no institutional proposal Spain-wide for paid care leave (Escobedo, 2022), and the current leave system does not guarantee the necessary flexibility and universal coverage for the most vulnerable families.

We also observed inconsistencies in preferences: half of the sample simultaneously indicated a preference for equal leave, but supported the extension of leave for mothers through pre- and post-natal leave and expressed a preference for transferable or mixed leave. These inconsistencies reflected that preferences are weakly formed due to the context in which Royal Decree Law 6/2019 was passed: via an urgent legislative procedure, without political opposition or media debate, and with apparent social consensus, despite the existing demand for an extension of the maternity leave. Moreover, policies that seek neutrality can lead to inequality by failing to consider the biological differences between motherhood and fatherhood, and the socio-occupational status of women relative to men (Escobedo, 2022).

The broad support for a new leave to protect the health of both the mother and baby (pre- and post-partum) showed that the equality objective of the current model may not meet the expressed preferences of mothers and fathers. There is a proven relationship between leave from work and a mother’s physical and mental health (Hewitt, Strazdins and Martin, 2017; Heshmati, Honkaniemi and Juárez, 2023), especially for those in precarious or single-parent situations (Bütikofer, Riise and Skira, 2021), which should be considered in the design of these policies. Additionally, a notable percentage of respondents who favoured equal parental leave entitlements expressed concern about the impact of a mother’s return to work on the baby’s emotional wellbeing. This suggests that pro-equality reforms may have overlooked the needs of infants, a group to be advocated for in terms of these policies (Moss, 2018; Escobedo, 2022; Gribble, 2023).

Our results provide information to be taken into account for future reforms of the parental leave system in Spain that are aligned with the preferences of mothers and fathers, who, together with babies, are the group most affected by these measures. Parental leave entitlements, as well as all other public policies to support parenting, should be reformulated through a new model that fits the preferences and needs of families.

Arnalds, Ásdís A.; Eydal, Guðný B. and Gíslason, Ingólfur V. (2022). “Paid Parental Leave in Iceland: Increasing Gender Equality at Home and on the Labour Market”. In: C. De La Porte; G. B. Eydal; J. Kauko; D. Nohrstedt; P. ’T Hart and B. S. Tranøy (eds.). Successful Public Policy in the Nordic Countries: Cases, Lessons, Challenges (pp. 370-387). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blum, Sonja; Dobrotić, Ivana; Kaufman, Gayle; Koslowski, Alison and Moss, Peter (2023). 19th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2023.

Brandth, Berit; Bungum, Brita and Kvande, Elin (2022). Fathers, Fathering and Parental Leaves. In: I. Dobrotic, S. Blum and A. Koslowski (eds.). Research Handbook on Leave Policy (pp. 172-184). Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bütikofer, Aline; Riise, Julie and Skira, Meghan M. (2021). “The Impact of Paid Maternity Leave on Maternal Health”. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 13(1): 67-105.

Cañero Ruiz, Julia (2022). “Feminismo andaluz y maternidades: Una aproximación desde los feminismos decoloniales”. Antropología Experimental, 22: 57-78.

Castellanos Serrano, Cristina; Recio Alcaide, Adela; Jiménez, Javier A. and Vega Martínez, Celia (2024). La reforma del sistema de permisos parentales: formas de uso y expectativas de influencia en la corresponsabilidad. Madrid: UNED.

Escobedo, Anna (2022). “Una oportunidad de ampliación y mejora del sistema español de licencias remuneradas parentales y por cuidados familiares”. IgualdadES, 7: 611-628.

Escot, Lorenzo; Fernández-Cornejo, Jose A.; Lafuente, Carmen and Poza, Carlos (2012). “Willingness of Spanish men to take maternity leave. Do firms’ strategies for reconciliation impinge on this?”. Sex Roles, 67: 29-42.

Escot, Lorenzo; Fernández-Cornejo, Jose A. and Poza, Carlos (2014). “Fathers’ Use of Childbirth Leave in Spain. The Effects of the 13-day Paternity Leave”. Population Research and Policy Review, 33: 419-453.

Farré, Lídia; González, Libertad; Hupkau, Claudia and Ruiz-Valenzuela, Jenifer (2024). “¿Qué sabemos sobre el uso de los permisos de paternidad en España?”. Estudios Seguridad Social. Available at: https://portaldatos.seg-social.gob.es/estudios/-/study_report/52542, access August 1, 2024.

Flaquer, Lluís and Escobedo, Anna (2014). “Licencias parentales y política social de la paternidad en España”. Cuadernos de Relaciones Laborales, 32(1): 69-99.

Fundación Cepaim (2023). Estado de las paternidades y cuidados en España. Plan Corresponsables. Madrid: Ministerio de Igualdad.

Gorjón, Lucía and Lizarraga, Imanol (2024). “Family-friendly Policies and Employment Equality: An Analysis of Maternitiy and Paternity Leave Equalization in Spain”. ISEAK Working Paper 2024/3.

Gribble, Karleen. D.; Smith, Julie P.; Gammeltoft, Tine; Ulep, Valerie; Van Esterik, Penelope; Craig, Lyn; Pereira-Kotze, Catherine; Chopra, Deepta; Siregar, Adiatma Y. M.; Hajizadeh, Mohammad and Mathisen, Roger (2023). “Breastfeeding and Infant Care as ‘Sexed’ Care Work: Reconsideration of the Three Rs to Enable Women’s Rights, Economic Empowerment, Nutrition and Health”. Frontiers in Public Health, 11.

Hernández, Enrique; Galais Gonzàlez, Carolina; Rico, Guillem; Muñoz, Jordi; Hierro, María José; Pannico, Roberto; Barbet, Berta; Marinova, Dani and Anduiza Perea, Eva (2021). POLAT Project. Spanish Political Attitudes Panel Dataset (Waves 1-6). Dipòsit Digital de Documents de la UAB.

Heshmati, Amy; Honkaniemi, Helena and Juárez, Sol P. (2023). “The Effect of Parental Leave on Parents’ Mental Health: a Systematic Review”. The Lancet Public Health, 8: 57-75.

Hewitt, Belinda; Strazdins, Lyndall and Martin, Bill (2017). “The Benefits of Paid Maternity Leave for Mothers' Post-partum Health and Wellbeing: Evidence from an Australian Evaluation”. Social Science & Medicine, 182: 97-105.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2022). Encuesta de Población Activa (EPA). Available at: https://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/index.htm?padre=5497, access August 1, 2024.

Lammi-Taskula, Johanna (2008). “Doing Fatherhood: Understanding the Gendered Use of Parental Leave in Finland”. Fathering, 6: 133-148.

Li, Qi; Knoester, Chris and Petts, Richard J. (2022). “Attitudes about Paid Parental Leave in the United States”. Sociological Focus, 55(1): 48-67.

Meil, Gerardo and Escobedo, Anna (2018). “Igualdad de Género y Permisos Parentales”. Revista Española de Sociología, 27(3 Supl.): 9-12.

Meil, Gerardo; Rogero-García, Jesús and Romero-Balsas, Pedro (2020). Los permisos para el cuidado de niños/as: evolución e implicaciones sociales y económicas. In: A. Blanco Martín; A. M. Chueca Sánchez; J. A. López Ruiz and S. Mora Rosado (coords.). Informe España 2020. Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas de Madrid.

Meil, Gerardo; Romero-Balsas, Pedro and Rogero-

García, Jesús (2018). “Parental Leave in Spain: Use, Motivations and Implications”. RES. Revista Española de Sociología, 27(3): 27-43.

Meil, Gerardo; Wall, Karin; Atalaia, Susana and Escobedo, Anna (2022). Trends towards De-gendering Leave Use in Spain and Portugal. In: I. Dobrotić; S. Blum and A. S. Koslowski (eds.). Research Handbook on Leave Policy: Parenting and Social Inequalities in a Global Perspective. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

McKay, Lindsey and Doucet, Andrea (2010). “Without Taking Away her Leave’: A Canadian Case Study of Couples’ Decisions on Fathers’ Use of Paid Leave”. Fathering, 8: 300-320.

Merino, Patricia (2017) Maternidad, igualdad y fraternidad: las madres como sujeto político en las sociedades poslaborales. Madrid: Clave Intelectual.

Moss, Peter (2018). “Parental Leave and Beyond: Some Reflections on 30 Years of International Networking”. Revista Española de Sociología, 27(3): 15-25.

Olsson, María I.T.; Grootel, Sanne van; Block, Katharina; Schuster, Carolin; Meeussen, Loes; Laar, Colette van and Martiny, Sarah E. (2023). “Gender Gap in Parental Leave Intentions: Evidence from 37 Countries”. Political psychology, 44(6): 1163-1192.

Pérez-Escamilla, Rafael; Tomori, Cecília; Hernández-

Cordero, Sonia; Baker, Phillip; Barros, Aluisio J. D; Bégin, France; Chapman, Donna J.; Grummer-Strawn, Laurence M.; McCoy, David; Menon, Purnima; Ribeiro Neves, Paulo A.; Piwoz, Ellen; Rollins, Nigel; Victora, Cesar G. and Richter, Linda (2023). “Breastfeeding: Crucially Important, but Increasingly Challenged in a Market-driven World”. The Lancet, 401(10375): 472-485.

Philipp, Marie-Fleur; Büchau, Silke; Schober, Pia S. and Spieß, C. Katharina (2023). “Parental Leave Policies, Usage Consequences, and Changing Normative Beliefs: Evidence From a Survey Experiment”. Gender & Society, 37(4): 493-523.

Romero-Balsas, Pedro M. (2012). “Fathers Taking Paternity Leave in Spain: Which Characteristics Foster and Which Hampers the Use of Paternity Leave?”. Sociologia E Politiche Sociali, 15(3): 106-131. doi: 10.3280/SP2012-SU3006

Saarikallio-Torp, Miia and Miettinen, Anneli (2021). “Family Leaves for Fathers: Non-users as a Test for Parental Leave Reforms”. Journal of European Social Policy, 31(2): 161-174.

Seguridad Social (2024). Revista de la Seguridad Social. Secretaría de Estado de la Seguridad Social y Pensiones. Available at: https://revista.seg-social.es, access August 1, 2024.

Twamley, Katherine and Schober, Pia (2019). “Shared Parental Leave: Exploring Variations in Attitudes, Eligibility, Knowledge and Take-up Intentions of Expectant Mothers in London”. Journal of Social Policy, 48(2): 387-407.

Figure A2. Determinants of preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements: gender attitudes towards parenting

Note: Estimates based on Model 2 presented in Table A2.

Table A2. Preferences regarding equal parental leave entitlements: logistic regression

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

|

|

Socio-demographic |

Attitudinal |

Full model |

|

|

Socio-demographic factors |

|||

|

Age |

-0.01+ |

-0.01 |

|

|

(0.01) |

(0.01) |

||

|

Mother |

-0.80*** |

-0.83*** |

|

|

(0.09) |

(0.10) |

||

|

Year of birth (ref. 2018) |

|||

|

2019 |

0.03 |

-0.04 |

|

|

(0.13) |

(0.15) |

||

|

2020 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

|

(0.12) |

(0.13) |

||

|

2021 |

0.01 |

0.01 |

|

|

(0.12) |

(0.13) |

||

|

Educational level (ref. Primary) |

|||

|

Secondary |

0.25 |

0.15 |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.27) |

||

|

University |

0.19 |

0.12 |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.28) |

||

|

Income (ref. <€300/month) |

|||

|

€ 301-600 |

-0.43* |

-0.44* |

|

|

(0.19) |

(0.23) |

||

|

€ 601-900 |

-0.30+ |

-0.29 |

|

|

(0.17) |

(0.20) |

||

|

€ 901-1.050 |

-0.24 |

-0.26 |

|

|

(0.18) |

(0.20) |

||

|

€ 1.051-1.200 |

0.12 |

0.26 |

|

|

(0.16) |

(0.18) |

||

|

€ 1.201-1.500 |

-0.13 |

-0.13 |

|

|

(0.16) |

(0.17) |

||

|

€ 1.501-1.800 |

-0.17 |

-0.22 |

|

|

(0.17) |

(0.19) |

||

|

€ 1.801-2.400 |

-0.02 |

-0.07 |

|

|

(0.16) |

(0.18) |

||

|

€ 2.401-3.000 |

0.04 |

0.03 |

|

|

(0.21) |

(0.23) |

||

|

€ 3.001-4.500 |

-0.17 |

-0.15 |

|

|

(0.27) |

(0.30) |

||

|

€ 4.501-6.000 |

0.49 |

0.65 |

|

|

(0.60) |

(0.60) |

||

|

More than € 6.000 |

-0.87 |

-0.90 |

|

|

(0.63) |

(0.59) |

||

|

Attitudinal factors |

|||

|

Male equally capable (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

-0.86*** |

-0.81*** |

|

|

(0.12) |

(0.12) |

||

|

Disagree |

-1.28*** |

-1.33*** |

|

|

(0.14) |

(0.15) |

||

|

Father essential for well-being (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0.08 |

0.04 |

|

|

(0.17) |

(0.19) |

||

|

Disagree |

-0.40 |

-0.09 |

|

|

(0.37) |

(0.38) |

||

|

Child suffers if mother works (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0.15 |

0.13 |

|

|

(0.09) |

(0.10) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.33** |

0.30** |

|

|

(0.10) |

(0.11) |

||

|

Men same responsibilities (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

-0.15 |

-0.24+ |

|

|

(0.14) |

(0.15) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.13 |

-0.21 |

|

|

(0.41) |

(0.43) |

||

|

Feminism (ref. Strongly opposed) |

|||

|

Somewhat opposed |

-0.49+ |

-0.49+ |

|

|

(0.26) |

(0.27) |

||

|

Indifferent |

-0.73** |

-0.62** |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.23) |

||

|

Somewhat supportive |

-0.62** |

-0.42+ |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.24) |

||

|

Strongly supportive |

-0.71** |

-0.48+ |

|

|

(0.25) |

(0.25) |

||

|

Political ideology |

-0.07*** |

-0.07** |

|

|

(0.02) |

(0.02) |

||

|

Constant |

0.84* |

1.07*** |

1.76*** |

|

(0.38) |

(0.27) |

(0.53) |

|

|

N |

3,097 |

2,869 |

2,854 |

Note: Data from an original survey and weighted by educational level and sex. Logistic regression coefficients and standard errors in brackets + p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Source: Data from an original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Table A3. Preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements: Multinomial regression (reference: non-transferable parental leave entitlements)

|

(1) |

(2) |

(3) |

|

|

Socio-demographic |

Attitudinal |

Full model |

|

|

Transferable (ref. non-transferable) |

|||

|

Age |

0.01 |

-0.00 |

|

|

(0.01) |

(0.01) |

||

|

Year of birth (ref. 2018) |

|||

|

2019 |

0.28 |

0.30 |

|

|

(0.20) |

(0.22) |

||

|

2020 |

0.13 |

0.11 |

|

|

(0.17) |

(0.18) |

||

|

2021 |

-0.35* |

-0.30+ |

|

|

(0.17) |

(0.18) |

||

|

Educational level (ref. Primary) |

|||

|

Secondary |

0.28 |

-0.22 |

|

|

(0.28) |

(0.39) |

||

|

University |

-0.00 |

-0.46 |

|

|

(0.29) |

(0.40) |

||

|

Income (ref. € 601-900 monthly) |

|||

|

Less than €300 |

0.05 |

0.45 |

|

|

(0.25) |

(0.30) |

||

|

€ 301-600 |

0.13 |

0.21 |

|

|

(0.29) |

(0.34) |

||

|

€ 901-1.050 |

0.18 |

0.20 |

|

|

(0.27) |

(0.30) |

||

|

€ 1.051-1.200 |

-0.06 |

-0.12 |

|

|

(0.24) |

(0.26) |

||

|

€ 1.201-1.500 |

0.01 |

0.07 |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.25) |

||

|

€ 1.501-1.800 |

-0.07 |

0.08 |

|

|

(0.25) |

(0.26) |

||

|

€ 1.801-2.400 |

-0.67** |

-0.53* |

|

|

(0.24) |

(0.25) |

||

|

€ 2.401-3.000 |

-0.73* |

-0.63* |

|

|

(0.30) |

(0.31) |

||

|

€ 3.001-4.500 |

-0.69+ |

-0.47 |

|

|

(0.37) |

(0.40) |

||

|

€ 4.501-6.000 |

0.11 |

0.16 |

|

|

(0.75) |

(0.75) |

||

|

More than € 6.000 |

1.85+ |

1.88 |

|

|

(1.08) |

(1.15) |

||

|

Female |

-0.12 |

-0.05 |

|

|

(0.13) |

(0.14) |

||

|

Attitudinal factors |

|||

|

Male equally capable (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0.26 |

0.26 |

|

|

(0.17) |

(0.17) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.46* |

0.53** |

|

|

(0.20) |

(0.20) |

||

|

Father essential for well-being (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

-0.14 |

-0.12 |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.24) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.19 |

0.13 |

|

|

(0.50) |

(0.55) |

||

|

Child suffers if mother works (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

-0.03 |

0.02 |

|

|

(0.14) |

(0.14) |

||

|

Disagree |

-0.48** |

-0.36* |

|

|

(0.15) |

(0.15) |

||

|

Men same responsibilities (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0.21 |

-0.01 |

|

|

(0.19) |

(0.20) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.32 |

0.03 |

|

|

(0.64) |

(0.64) |

||

|

Feminism (ref. Strongly opposed) |

|||

|

Somewhat opposed |

-0.00 |

0.01 |

|

|

(0.36) |

(0.37) |

||

|

Indifferent |

0.46 |

0.44 |

|

|

(0.30) |

(0.31) |

||

|

Somewhat in favour |

0.22 |

0.30 |

|

|

(0.31) |

(0.32) |

||

|

Strongly in favour |

-0.66* |

-0.57+ |

|

|

(0.32) |

(0.33) |

||

|

Political ideology |

0.04 |

0.04 |

|

|

(0.03) |

(0.03) |

||

|

Constant |

0.56 |

0.51 |

0.88 |

|

(0.52) |

(0.35) |

(0.71) |

|

|

Mixed (ref. Non-transferable) |

|||

|

Age |

0.01 |

0.00 |

|

|

(0.01) |

(0.01) |

||

|

Year of birth (ref. 2018) |

|||

|

2019 |

0.12 |

0.21 |

|

|

(0.19) |

(0.21) |

||

|

2020 |

0.02 |

0.04 |

|

|

(0.16) |

(0.17) |

||

|

2021 |

-0.19 |

-0.15 |

|

|

(0.16) |

(0.17) |

||

|

Educational level (ref. Primary) |

|||

|

Secondary |

0.87** |

0.37 |

|

|

(0.31) |

(0.41) |

||

|

University |

0.84** |

0.36 |

|

|

(0.31) |

(0.42) |

||

|

Income (ref. € 601-900 monthly) |

0.01 |

0.44 |

|

|

Less than €300 |

(0.25) |

(0.29) |

|

|

€ 301-600 |

-0.11 |

0.12 |

|

|

(0.29) |

(0.33) |

||

|

€ 901-1.050 |

0.07 |

0.19 |

|

|

(0.27) |

(0.29) |

||

|

€ 1.051-1.200 |

0.07 |

0.08 |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.25) |

||

|

€ 1.201-1.500 |

0.04 |

0.08 |

|

|

(0.22) |

(0.24) |

||

|

€ 1.501-1.800 |

-0.00 |

0.14 |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.25) |

||

|

€ 1.801-2.400 |

-0.31 |

-0.17 |

|

|

(0.22) |

(0.24) |

||

|

€ 2.401-3.000 |

-0.38 |

-0.28 |

|

|

(0.27) |

(0.29) |

||

|

€ 3.001-4.500 |

-0.53 |

-0.27 |

|

|

(0.33) |

(0.36) |

||

|

€ 4.501-6.000 |

-0.20 |

-0.01 |

|

|

(0.72) |

(0.74) |

||

|

More than € 6.000 |

0.59 |

0.72 |

|

|

(1.27) |

(1.28) |

||

|

Female |

0.08 |

0.09 |

|

|

(0.12) |

(0.13) |

||

|

Attitudinal factors |

|||

|

Male equally capable (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0.24 |

0.24 |

|

|

(0.16) |

(0.17) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.33+ |

0.34+ |

|

|

(0.20) |

(0.20) |

||

|

Father essential for well-being (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

-0.40+ |

-0.39+ |

|

|

(0.23) |

(0.24) |

||

|

Disagree |

-0.31 |

-0.31 |

|

|

(0.52) |

(0.54) |

||

|

Child suffers if mother works (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

0.10 |

0.13 |

|

|

(0.13) |

(0.13) |

||

|

Disagree |

-0.27+ |

-0.23+ |

|

|

(0.14) |

(0.14) |

||

|

Men same responsibilities (ref. Agree) |

|||

|

Neither agree nor disagree |

-0.14 |

-0.17 |

|

|

(0.18) |

(0.20) |

||

|

Disagree |

0.28 |

0.09 |

|

|

(0.67) |

(0.66) |

||

|

Feminism (ref. Strongly opposed) |

|||

|

Somewhat opposed |

0.04 |

0.00 |

|

|

(0.35) |

(0.35) |

||

|

Indifferent |

0.42 |

0.36 |

|

|

(0.30) |

(0.30) |

||

|

Somewhat in favour |

0.25 |

0.19 |

|

|

(0.30) |

(0.31) |

||

|

Strongly in favour |

-0.48 |

-0.57+ |

|

|

(0.31) |

(0.32) |

||

|

Political ideology |

-0.04 |

-0.04 |

|

|

(0.03) |

(0.03) |

||

|

Constant |

-0.15 |

1.09** |

0.70 |

|

(0.52) |

(0.33) |

(0.68) |

|

|

N |

3,102 |

2,880 |

2,866 |

Note: Data from an original survey and weighted by educational level and sex. Multinomial regression coefficients and standard errors in brackets + p < 0.10; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

Source: Data from an original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

1 This change was reflected in the terminology: maternity and paternity leave were renamed childbirth and childcare leave; breastfeeding leave became infant care leave; and an allowance for joint responsibility for infant care was introduced.

2 Other European countries have separate maternity leave, followed by paid and partially transferable parental leave, in line with existing European directives. Maternity leave is thus designed to protect maternal and child health and paternal co-responsibility is encouraged through non-transferable parental leave quotas or bonuses (Saarikallio-Torp and Miettinen, 2021). In countries such as Sweden, there is only extensive and partially transferable parental leave.

3 The parental leave reform ignored demands for extended maternity leave from mothers’ groups, breastfeeding and parenting groups, as well as healthcare professionals. La Leche group of Seville had asked for this extension since 1999. In 2004, Vía Láctea in Zaragoza held rallies calling for a six-month maternity leave and one-month paternity leave. In 2007 there was also a Popular Legislative Initiative, initiated by female health workers in Fuensalida (Toledo) and endorsed by breastfeeding support groups, but it failed to obtain the number of signatures required for the Initiative to succeed. FEDALMA has also called for the extension of maternity leave to six months, ideally to twelve months.

4 This is in addition to other currents that are also part of the debate, such as ecofeminism.

5 This expectation is in line with studies from other countries (Gribble et al., 2023; Philipp et al., 2023; Li, Knoester and Petts, 2022; Olsson et al., 2023).

6 This expectation is consistent with previous studies linking ideological conservatism to lower demand for parental leave (Li, Knoester and Petts, 2022).

7 The survey was funded within the project “Longer paternity leave, fairer labour markets? Evidence from the paternity leave reform in 2021 in Spain FAIRLEAVE” (R&D&I 2020 “Knowledge Generation” Project PID2020-119226GA-I00, PI: Marinova). The survey was approved by the Commission on Ethics in Animal and Human Experimentation of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona in May 2022.

8 In addition to socio-economic characteristics, some difficulties were encountered in obtaining a gender-balanced sample. Only 35 % of online respondents were male. This percentage was even lower in the face-to-face interviews, totalling only 28 %, despite having prioritised approaching men in children’s playgrounds. The results of all regression models presented below were weighted by educational attainment and gender, according to official statistics (see Table A1 in the Appendix).

9 Only twenty people chose the option “longer for fathers”. These responses were excluded due to lack of statistical power.

10 Further analyses in the Appendix show the relationship between gender attitudes, feminist attitudes and political ideology, on the one hand, and preferences regarding parental leave transferability, on the other hand (Figures A2-3). While gender attitudes around parenting and feminism do not clearly structure preferences regarding the parental leave system, people of conservative ideology prefer full transferability the most (with a 40 % probability), followed by the mixed system. Within left-wing ideology, non-transferable leave entitlements were the least preferred option, ranking even lower than fully transferable leave entitlements. Mixed parental leave entitlements were the most favoured choice, with a substantial preference margin of over 50 %. In short, the current non-transferable parental leave was the least desired among all ideological profiles, with no statistically significant differences being observed between the left and the right in preferences for this system.

Table 1. Preferences regarding equality and transferability of parental leaves

|

Transferability |

Equality |

|||

|

Longer for the mother |

Of equal length |

Longer for the father |

Total |

|

|

Non-transferable |

229 (7.6 %) |

343 (10.4 %) |

1 (0.1 %) |

573 (18.0 %) |

|

Transferable |

602 (20.0 %) |

479 (15.7 %) |

11 (0.4 %) |

1,092 (36.0 %) |

|

Mixed |

766 (23.5 %) |

703 (22.2 %) |

8 (0.4 %) |

1,477 (46 %) |

|

Total |

1,597 (48.2 %) |

1,525 (51.0 %) |

20 (0.8 %) |

3,142 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Table 2. Preferences regarding new parental leaves. A. Pre-partum and B. Post-partum, and preferences regarding equality

|

Equality |

Pregnancy protection leave |

Leave to facilitate recovery from childbirth |

||

|

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

|

Of equal length |

1,489 (47.2 %) |

38 (1.1 %) |

1,475 (47.1 %) |

47 (1.3 %) |

|

Longer for mothers |

1,546 (49.4 %) |

52 (1.6 %) |

1,531 (49.3 %) |

54 (1.6 %) |

|

Longer for fathers |

18 (0.7 %) |

2 (0.1 %) |

18 (0.01 %) |

2 (0.01 %) |

|

Total |

3,053 (97.3 %) |

92 (2.75 %) |

3,024 (97.1 %) |

103 (2.93 %) |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Figure 1. Preferences for A. Equality and B. Transferability of Entitlements, by sex

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Figure 2. Determinants of preferences regarding equal parental leave entitlements: gender attitudes towards parenting

Note: Predicted probabilities based on Model 3 in Table A2.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Figure 3. Determinants of preferences regarding equal parental leave entitlements: attitudes towards feminism and political ideology

Note: Predicted probabilities based on Model 3 in Table A2.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Figure 4. Determinants of preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements: Socio-demographic factors

Note: Predicted probabilities based on Model 1 in Table A3.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

RECEPTION: March 07, 2024

REVIEW: June 28, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: October 11, 2024

Source: Data from an original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Figure A1. Preferences regarding new leave Entitlements A. Prepartum and B. Postpartum, by sex of parent

Source: Data from an original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Figure A3. Determinants of preferences regarding equal parental leave entitlements: attitudes towards feminism and political ideology

Note: Estimates based on Model 2 presented in Table A3.

Table A1. Weighting of the sample by gender and educational level

|

In the population |

In the sample |

|||

|

Women, 25-44 |

Men, 25-44 |

Women |

Men |

|

|

Primary education or below |

24.2 |

34.5 |

11.4 |

19.7 |

|

Secondary education |

23.2 |

24 |

19.5 |

21.7 |

|

University degree or above |

52.6 |

41.6 |

69.1 |

58.5 |

Source: Population statistics from the Spanish Ministry of Education. Available at: https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/servicios-al-ciudadano/estadisticas/laborales/epa.html

Source: Data from an original survey of mothers and fathers of children born between 2018 and 2021. N=3100.

Table A2. Preferences regarding equal parental leave entitlements: logistic regression (Continuation)

Table A3. Preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements: Multinomial regression (reference: non-transferable parental leave entitlements) (Continuation)

Table A3. Preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements: Multinomial regression (reference: non-transferable parental leave entitlements) (Continuation)

Table A3. Preferences regarding the transferability of parental leave entitlements: Multinomial regression (reference: non-transferable parental leave entitlements) (Continuation)