The Plurality of Information Consumption

Habits on Digital Social Networks.

Are All Media Agents Equally Polarising?

La pluralidad de hábitos de consumo de información en las redes sociales digitales. ¿Todos los agentes polarizan por igual?

Pedro Vivo Filardi and José Manuel Robles Morales

|

Key words Echo Chambers

|

Abstract Various studies have noted the proliferation of information channels in the digital society. Theories of selective exposure and echo chambers on social networks characterise some of the dynamics that have emerged in these new information environments. This research examined the information exposure preferences of a sample of politicised users on the social network Twitter. The variable of interest was the different agents in the information landscape, ranging from traditional media to new opinion leaders (“influencers”). The results revealed the existence of strong partisan polarisation, mainly along the left-right axis. It was also observed that new digital agents had more polarised audiences than traditional ones, which could be an incentive for adopting more radical political positions. |

|

Palabras clave Cámaras de eco

|

Resumen Diversos estudios señalan la proliferación de canales de información en la sociedad digital. Las teorías de la exposición selectiva y las cámaras de eco en las redes sociales caracterizan algunas dinámicas que surgen en estos nuevos entornos informacionales. En esta investigación se han estudiado las preferencias de exposición informativa de una muestra de usuarios politizados en la red social Twitter. La variable de interés es los distintos agentes presentes en el entorno informativo, que van desde los medios tradicionales hasta los nuevos líderes de opinión (influencers). Los resultados revelan una fuerte polarización partidista, principalmente en torno al eje izquierda-derecha. También se ha observado que los nuevos agentes digitales tienen audiencias más polarizadas que los tradicionales, lo que podría ser un incentivo para adoptar posiciones políticas más radicales. |

Citation

Vivo Filardi, Pedro; Robles Morales, José Manuel (2025). «The Plurality of Information Consumption Habits on Digital Social Networks. Are All Media Agents Equally Polarising?». Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 191: 113-128. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.191.113-128)

Pedro Vivo Filardi: Universidad Complutense de Madrid | pedroviv@ucm.es

José Manuel Robles Morales: Universidad Complutense de Madrid | jmrobles@ucm.es

The political consequences of the increasing availability and variety of opinion and information sources have been the object of study since the emergence of cable television (Hopkins and Ladd, 2013; Webster, 2005). Phenomena such as the fragmentation and polarisation of audiences are the result of a trend towards progressively more personalised content. From the consumer perspective, this incursion of choices has given rise to the study of psychosocial processes of selective exposure or consumption (Stroud, 2017). It has been observed that individuals show a preference for content that is either in line with or confirms their already established beliefs. In addition to the partisan preference, the concentration of audiences around politically-defined channel clusters could also imply an avoidance of anything that does not coincide with their way of thinking. It is this possibility that has raised the most concern, as this supposed isolation would challenge some of the principles of dialogue and encounter that had been established as democratic ideals decades before (Habermas, 1991).

Linked to political polarisation studies, theories of selective exposure have found the Internet to be a unique space to further explore the relationship between political behaviour and exposure to an increasingly varied supply of information (Garrett, 2009). Examples of these new possibilities include the rise in political blogs with a clear political polarisation (Adamic and Glance, 2005). The absence of relationships between people participating in different discussion spaces has therefore led to talk of genuine virtual ghettos (Johnson, Bichard and Zhang, 2009). The concept of cyberbalkanisation is very much on the rise, particularly within the context of digital social networks. Individuals tend to organise themselves into opposing political communities, only responding to opinions and information that do not challenge their views. Intergroup contacts are scarce and, if any, they are characterised by an undemocratic spirit (Sunstein, 2018). Even during the age of hyperconnectivity, individuals have the ability to filter and select which messages, people or content they wish to interact with, actively building a personal public sphere (Light, 2014). Whether or not these spheres are in fact ideological bubbles is one of the debates of our time (Pariser, 2012). Specifically, within the realms of political communication studies, the “echo chambers” metaphor has been employed to account for the process of reinforcement and amplification of beliefs as a result of a reverberation structure.

Based on this diagnosis, this article introduces the “structure and composition” of the digital communication space as a study variable. We are specifically interested in understanding the role of the different agents in the digital public space, how these agents play a polarising function and what positions they occupy in the public debate. In other words, we focus on the different media and agents that lead social and political communication on Twitter, from traditional to emerging. The study of this conglomerate of actors, known as the “information environment”, will enable us to delve further into the processes of the fragmentation and polarisation of audiences, introducing a differential element in the study of exposure to information. In order to do so, our research is structured as follows: Firstly, we will review the theoretical discussion surrounding the concepts of selective exposure (Festinger, 1957), echo chambers and polarisation. We will then go on to review the characteristics of the media ecosystem and communication agents in digital social networks, taking into consideration the potentialities, transformations and challenges to which the incursion of digital spaces has given rise. Lastly, we will examine the polarisation of exposure to these agents in a case study on Twitter.

Managing abundance: digital social network content curation

The ability to choose is a key aspect of how digitalisation is characterised. In recent decades, our options for accessing information have grown exponentially. While this media incursion has been celebrated with optimism, there have also been warnings issued concerning the risks involved: individual choice could entail mechanisms that would ultimately alienate citizens from the dynamics of deliberation (Aelst et al., 2017). Since pioneering studies such as those by Klapper (1960), the approach to media no longer arises from mass effects but from certain microsociological foundations, including individual predispositions, psychological biases, decision theories, the study of rationality and group norms. This shift towards individual-centred research has been exacerbated by the importance of individual motivations within the context of the drastic increase in digital content choice opportunities (Prior, 2005). Therefore, from a “content curation” perspective, the individual is seen as a manager of the various information flows that intersect them; while they choose and reinforce specific contents, they block, censor or discard others (Thorson and Wells, 2016). Curation as an administration of abundance is not the free and indeterminate exercise of choice over equally-likely flows, but rather, as is the case with all actions, it is subject to both social and psychological mechanisms and structural constraints. Thus, the phenomenon of selective exposure (Stroud, 2017), the tendency to consume related content and echo chambers, i.e. the generation of closed systems of information circulation between different communities, have been the subject of academic study.

Selective exposure and avoidance

Various mechanisms have been suggested regarding selective exposure which could perhaps explain this phenomenon. These have included the reduction of the stress involved in exposure to cognitive conflicts (Festinger, 1957), the attribution of credibility and a tendency to rely more on information that is aligned with our beliefs (Metzger, Hartsell and Flanagin, 2020), among others. Within the context of this research, the predisposition to systematically select content that reinforces pre-existing beliefs—whatever the cause or basis—is of interest only insofar as it can generate additional potentially harmful consequences such as polarisation under certain conditions. As an individual phenomenon, selective exposure, whether considered on the basis of the theories of psychological biases or of decision heuristics, can be understood as a perfectly expected and interpretable fact. It comes as no surprise that evidence of its existence has been found (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2011; Peterson, Goel and Iyengar, 2021; Stroud, 2008). Nevertheless, some interpretations of this theory could be erroneous. While selective exposure implies an information bias, it does not necessarily indicate the complete absence of other communicative practices that include alternative sources, even if they are less common.

This is of particular relevance, as the lack of exposure to alternative sources is precisely the main issue to be taken into account in contexts of democratic communication (Mutz, 2002). It has in fact been argued that access to selective information has become over-dimensioned and that, in practice, many users do not avoid discordant information, notwithstanding the fact that they generally opt for the most related media (Garrett, 2009; Garrett, Carnahan and Lynch, 2013).

However, some of the limitations of selective exposure studies within the context of our research are linked to the scope of application. As regards digital social networks, our object of study, exposure patterns are far removed from the traditional scenario of the television or radio consumer. Within these virtual spaces, information consumption is, in part, a community experience and is conditioned by ties that are both created and unravelled. The social network approach makes it possible to represent how the circulation of and access to information and opinions of different agents is modulated by the presence of communities, often formed by links based on homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin and Cook, 2001). Thus, on social networks, exposure to information itself is inseparable from a connection with and disconnection from other users. This community dimension of exposure acquires political relevance when the assortativity concerning the formation of links is conditioned by processes of affective polarisation and situations of conflict between groups.

However, the potential of digital social networks to foster echo chambers or disconnected communities can be further nuanced by another network phenomenon—the so-called weak ties and their capacity to disseminate information via social networking platforms (Granovetter, 1973). A distinction can therefore be made between selective and forced exposure (Dahlgren, 2022), the latter referring to exposure that is not voluntarily sought, but is instead the result of its circulation by way of communities.

Digital social networks echo chambers

Some authors have studied the presence of “echo chambers” on digital social networks and have faced ongoing challenges as regards their conceptualisation and measurement (Spohr, 2017). It has been observed that digitally mediated debates present significant biases with respect to the dissemination of information related to the presence of communities (Cinelli et al., 2021). The intensity of this polarity between communities on Twitter also depends on the nature of the debate but, in general, partisan bias can be identified in relation to the dissemination of both opinion and information (Barberá et al., 2015). Even on social networks such as Instagram, which is in principle less politicised than Twitter or Facebook, the phenomenon of selective avoidance of rival political leaders has been found to be widespread (Parmelee and Roman, 2020). The presence of echo chambers in scientific controversies has also been highlighted (Quattrociocchi, Scala and Sunstein, 2016; Williams et al., 2015).

In terms of assessing the existence of the echo chamber phenomenon, there is a diverse range of methodologies and approaches that ultimately impact the outcome. A systematic review has demonstrated how research with survey data does not support their existence, while most studies of digital behaviours do account for both of these processes of fragmentation and polarisation (Terren and Borge-Bravo, 2021).

Within the latter, interaction networks are often used as a means to assess the level of clustering and the absence of ties that intersect different communities (Aragón et al., 2013; Valle and Bravo 2018; Grömping, 2014). Some investigations have relativised the importance of these echo chambers (Conover et al., 2011). They have demonstrated that, despite the polarisation observed in the retweet network on Twitter, individuals are relatively exposed to the other extreme through mentions. Similarly, some researchers have suggested that, even when a bipolar structure has been identified, the poles of the public debates studied remain sufficiently connected (Bruns, 2017; Weeks, Ksiazek and Holbert, 2016). Finally, duplicate networks have been employed in order to show the overlap between communities (Dokuka et al., 2018). Along the lines discussed earlier, critical observations of the echo chamber concept from the perspective of social network analysis point to the role of both weak ties and bridges between communities (Bakshy, Messing and Adamic, 2015; Garimella et al., 2018).

In short, the study of echo chambers shows significant disparities in terms of results, which can be explained by differences in methodologies, measures and objects of study. The detachment from the rigid way in which the concept is often perceived is a good starting point. Therefore, both the absence of clustering and the total lack of communication between communities are fictitious scenarios, and thus not particularly compatible with human sociability (Geiß et al., 2021).

Political and affective polarisation

Just as cable television was optimistically welcomed, the expansion of the Internet was celebrated as an opportunity to develop new means of democratic participation (Hacker and Dijk, 2000). However, some critical voices began to warn of the risks posed by these new spaces for citizen participation, with political polarisation being the phenomenon that has come to arouse the most interest and concern (Gentzkow and Shapiro, 2011). Despite its long tradition, the emergence of the Internet contributed to resituating the study of this socio-political process. In particular, as within the digital context, new forms of fragmentation and confrontation have emerged as a result of the specific characteristics imposed by these digital communication and participation spaces. In this sense, Sunstein (2018) stated that, on the Internet, citizens are organised around homogeneous communities in which there is an exposure to related information and a dynamic reinforcement and normative adjustment. The group-based and identity nature of the phenomenon has been studied from the perspective of what has been called affective polarisation; pointing to a climate of intergroup hostility and aversion to the other, beyond agreement or disagreement with specific policies (Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes, 2012). This attitudinal and emotional entrenchment has two consequences as regards public debate: communication between communities is decreasing and, when it occurs, it unfolds by way of uncivil discourse (Lee, Liang and Tang, 2019). Lastly, it has been observed that users who are driven by feelings of animosity often block or break ties with political opponents (Merten, 2021). This type of analysis has been successfully applied in Spain to highlight the important role of affective polarisation in the context of Spanish political debate (Garrido, Martínez and Mora, 2021; Miller, 2023; Martín et al., 2024).

Media and information environment: from the mainstream to the new digital agents

One of the key concepts in understanding the structure of information networks and their relationship with selective exposure and polarisation processes is the information environment (Skovsgaard, Shehata and Strömbäck, 2016; Aelst et al., 2017). This environment can be described as the network of information processes and agents in which individuals are inserted, where they contribute to both maintenance and transformation by way of their own actions and beliefs. In this sense, digital social networks such as Twitter are characterised by a significant heterogeneity of information disseminating agents; in these spaces, ordinary citizens, media, organisations and political parties (among others) coexist. As regards the media, it is important to highlight the rise of digital native media, i.e. those whose original means of support is the internet (Negredo et al., 2020). Despite traditional media having also been digitised, there could be differences regarding the nature of their audiences. However, we must pay attention to the emergence of digitally native media, as is the case with populist digital media, which generate audience niches and are assiduously consulted by certain related sectors on the political spectrum (Müller and Schulz, 2021).

On the other hand, in addition to traditional and digital native agents, the phenomenon of disintermediation has enabled certain citizens to achieve significant levels of influence and centrality, without the need to affiliate with institutions or media (Robles and Córdoba, 2019). Although these users are not as popular as traditional agents in terms of “followers”, they play a very active role as opinion leaders (Bastos and Mercea 2016; Dubois and Gaffney, 2014). Finally, the journalist is a figure that straddles traditional and alternative agents. It has been observed that, while new digital journalists are generally professionally linked to media outlets, they try to build a more approachable profile on social networks, dispensing with the ideal of objectivity and seeking to connect with their audience, creating a personal brand of their own (Molyneux, 2015). The basic typology of the actors within the digital information environment encompasses native media, digital journalists and new digital leaders, alongside political leaders and traditional media. This study, which incorporates the information environment as an innovative aspect for the analysis of polarisation processes, uses these five categories as analytical reference points.

The position occupied in this information area and the processes that emerge are not only an ex novo product of digital activity, as offline dynamics also play a role. In this regard, the concept of audience fragmentation generated predictions regarding reduced inequality in the media, i.e. a change in the power law distribution that characterises these audiences, in which a few media outlets monopolise the majority of the audience. Promising a horizontal structure, the emergence of new actors on digital social networks might generate balance. This contrasts with some evidence suggesting that such unequal distribution persists. Thus, as a result of their popularity, traditional agents continue to play an essential role in virtual spaces (Webster and Ksiazek, 2012).

The concept of the information environment is therefore connected with the notions of selective exposure, echo chambers and polarisation. When “media” is used as an umbrella term, the ability to discern how various agents engage in this virtual arena—each with different inertias, positions, incentives and diverse impacts as they interact with users—is lost.

In line with the above, we will study the extent to which the contexts of political polarisation are related to structures of exposure to information transmitted by different types of agents. In other words, we will examine whether or not there are significant partisan biases in the consumption of and exposure to information, to wit:

RQ1. What is the structure of information exposure in the context of this research?

RQ2. What is the role that the different communication agents play in the structure of information exposure?

Our hypothesis is that, unlike studies that do not disaggregate the analysis of exposure to political information on digital social networks by typology of agents, the diversity and complexity of this type of information environment will lead to different patterns of information consumption being identified. This could present nuances between some of the extreme positions we have observed as regards the existence of exposure polarisation and echo chambers.

This article takes the public debate on digital social networks (Twitter) in Spain as a case study. The polarised nature of public and political opinion in Spain makes this case study a test bed for our hypotheses. Additionally, Twitter was selected because it is the social network chosen by citizens and institutions in Spain to engage in discussion and tendentiously polarise public debate.

To select the period for analysis, we decided to download data for a timeline that did not coincide with electoral or institutionally relevant processes. Our interest was focused on how the digital public sphere is structured in Spain, and not so much on the digital debate during a particular electoral campaign. For this reason, the download was carried out during the months of February-April 2023.

This research is located within the context of the Spanish political system, namely the presence of four major parties that monopolise partisan affiliation and support. Two of the parties, Vox and Unidas Podemos-Sumar, situated at the extreme right and the extreme left, respectively, emerged as an alternative to the two-party political system which prevailed in the first four decades of democracy in Spain (PP and PSOE). The raw data of this research are the preferences of politicised citizens and supporters of the respective parties as regards access to opinion and information. This division, which is more subtle than the one normally observed between the left and the right, will enable us to introduce another level of analysis: the difference between traditional and alternative parties. However, it has been observed that Spanish online political communication demonstrates that there is a polarised structure in two large blocks, particularly in major debates (Robles et al., 2019). The divisions on both sides of the political spectrum therefore do not appear to have their own substance in transversal debates.

Echo chambers and selective exposure patterns as found on Twitter have been studied by using different data sources. This social network enables several types of public relationships, which can be classified as follows:

- Support: “re-Tweet” and “like”.

- Dialogue/Controversial: “reply” and “mention”.

- Exposure and friendship: “follow”.

Within the context of polarisation studies, retweet networks have often been used in order to locate users in communities and determine cluster communication. On the other hand, “replies” and “mentions” are useful in terms of assessing the actual interaction between different parties and their nature, especially in relation to uncivil behaviour.

We have chosen the “follow” relationship because it involves a deliberate action that is coherent with the concept of selective exposure. It also reflects patterns of content avoidance and curation, either because a user decides not to follow another or because they end the relationship by unfollowing. Following another user involves being exposed to their digital output, which will appear in the “feed”, without taking into consideration the degree of support or affinity. There are other means of accidental and forced exposure, such as friends’ interactions with other users, or those recommended by the algorithms. However, the “follow” relationship allows the collection of information regarding the conscious choices or revealed preferences of individuals.

The first step was to obtain the sample of politicised users, the size of which was limited by the Twitter API restrictions in terms of providing data regarding “follows”. We considered the re-Tweets (RTs) of tweets by political leaders of the four parties to be a sign of political support or affinity. Of all the users, those whose description contained terms suggesting a relationship of militancy or holding public office, such as “mayor”, “congress”, etc., were eliminated. Lastly, a sample of 1000 users from each party was obtained through random selection. The complete friendship network from each of the 4000 users was downloaded. In other words, all the users they “followed”. Thus, our research started from politically located users and their preferences as regards the accounts they followed.

Information environment agents

Next, in order to obtain the main agents of social and political communication, we put together the top-500 ranking of the accounts that were most followed by users supportive of each party. In total, given that there were overlaps, 1469 users were obtained. Subsequently, these accounts were manually classified according to the following criteria (other types of profiles were discarded):

- Traditional media: accounts originating from television, radio or print media.

- Digital native media: digital native media.

- Traditional opinion leader: accounts belonging to individuals who regularly participated in the media, such as journalists, editors, communicators and talk-show hosts.

- Political leaders: users who occupied or had previously occupied institutional political positions.

- Traditional parties.

- Centre-Right: Partido Popular (People’s Party).

- Centre-Left: Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party).

- New political parties.

- Left: Unidas Podemos.

- Right: Vox.

- Traditional parties.

- Digital opinion leaders: users who generated political opinion with no link to institutions or media, such as “influencers”, “YouTubers”, etc.

In order to meet the objectives of this research, a methodological approach organised in a series of steps was used.

- Firstly, an analysis was undertaken by means of duplication networks in which:

The nodes represented the media and communication agents of our information environment.

The edges represented that at least one user in our sample simultaneously followed two agents.

- Secondly, each of the media outlets (node) was assigned the colour corresponding to the major political ideology of its “followers” (the plus sign if they followed the PSOE, a circle if they followed Unidas-Podemos, a triangle if they followed the Partido Popular and a star if they followed Vox).

- Thirdly, the degree of exposure to non-affinity content in ideological terms was measured using the right-left graph partition.

- Fourthly, a colour was allocated to the nodes that represented the type of agent belonging to the information environment (traditional media, digital native media, journalists, political leaders and digital leaders).

- Fifthly and finally, the analysis was refined by undertaking duplication networks filtering by type of agent, only including the most relevant nodes.

This structure enabled us to offer information which further facilitated a step-by-step exploration of the structure of the information environment in our case study. It also contributed to enhancing our understanding of how this environment is key to grasping processes such as political polarisation.

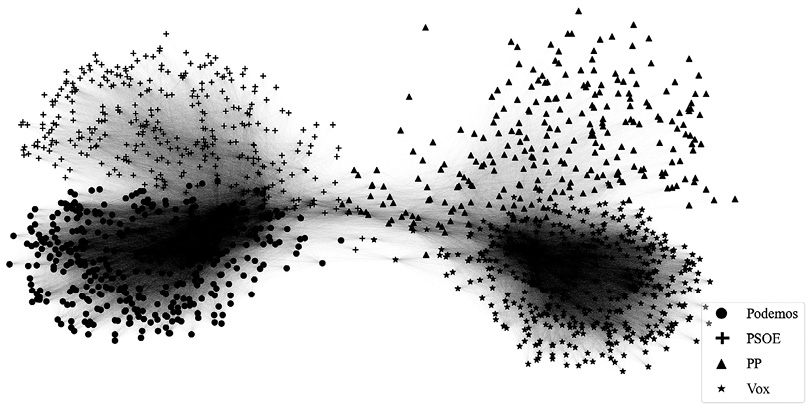

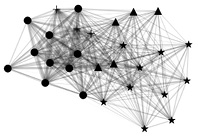

Phases 1 and 2: Duplication networks and ideological contribution to audiences

In order to represent the structure of the exposure, we used duplication or “co-follow” networks. In this type of network, each media outlet constitutes a node, while an arc between two agents indicates that at least one user in our sample simultaneously followed the two nodes. The weighting of the arc is thus the percentage of these users that incur this type of “co-following”.

For ease of understanding, colours were assigned to the nodes in the figure according to the largest partisan source of “followers”. That is to say, if the majority of the audience for a media outlet came from supporters (“followers”) of the PSOE, that media outlet will take the form of a plus sign; and so on as explained above. Therefore, the shape of our network makes sense; the four blocks that appear in the network correspond to groupings of agents for whom there was a partisan “co-follow” bias. Intuitively, the nodes that appeared more in the centre were those with more egalitarian audiences, while those located at the extremes had unequal audiences, in which most of their components corresponded to a single party. On the other hand, the presence of the two large constellations of nodes corresponded to the parties on the left and right. Delving deeper, the nodes (medium) located in the centre of each block represented those which have left- or right-leaning audiences, but without a specific partisan bias.

Phase 3: Exposure to non-affinity content

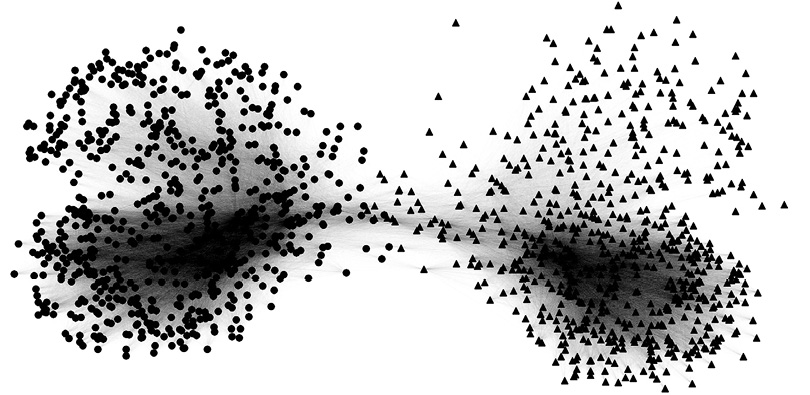

The External-Internal index (E-I index) and the Isolation Index were used to quantify the degree of exposure to non-affinity content. Given the specific nature of the Isolation Index, the assumption for calculation purposes is that the set of media and agents is split in two. However, so far we have not made any assumptions regarding the political orientation of the media, other than allocating colours to them according to their maximum audience source for illustrative purposes. The literature demonstrates that these partitions are often undertaken manually or by way of surveys that ask citizens about the ideological orientation of the different media. Having included agents of various types, some less popular, manual or survey-based classification methods would give rise to errors that could potentially taint the results. In our case, a community analysis using Louvain’s method was undertaken in order to classify the nodes, in line with the network approach implemented. This technique yielded two clearly defined blocks, the one on the left (represented with circles) and the one on the right (represented with triangles).

The E-I index was defined as shown below, where EF is the total “follows” of users in line with a party x to the agents of the opposite party, and IF is the total number of “follows” for agents of the partition to which they belong. For example, the index for Vox would be calculated by measuring the exposure of users with values in line with Vox to the nodes of the partition represented with circles as seen in Figure 2, versus the exposure to the nodes of the partition represented with triangles. An interpretation can be immediately made: it ranges from -1 (if all users of a party follow only users of their political orientation) to 0 (if it is even). This index was therefore calculated for each political party.

__9.png)

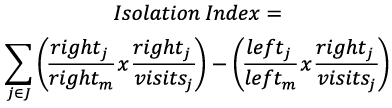

The Isolation Index has already been employed in a comparable context (Peterson). It does not assume any particular orientation of the agents; rather, it presupposes a two-way partition of the users who consume the media, namely those who follow them.

In order to construct the partition of the users, they were simply grouped into two different blocks, left and right, according to their political party. This index was calculated for each type of communication agent. J therefore represents the set of agents of one type, right and left, the total number of “follows” of each agent from right- or left-wing users, while visits consists of the sum of both. Lastly, right and left represent the total number of “follows” of all types of agents in question. The index ranges from 0 (when all users follow the same agents equally) and 1 (when there is no common exposure). Conversely, this index was calculated across the entire network or set of relationships, and was therefore a good measure of the polarisation of exposure to the network.

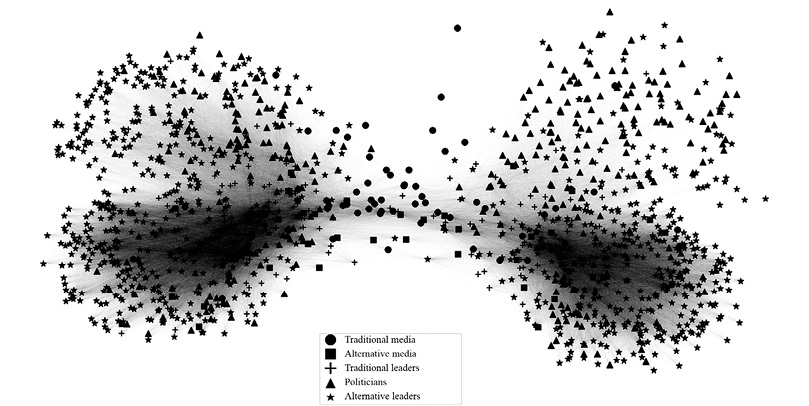

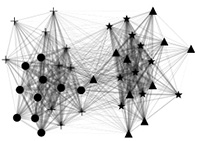

Phase 4: Agent typology

When all communication agents were considered, as shown in Figure 2, two poles can be observed, right and left. However, a further division can be seen in each of them which consists of constellations related to the two parties, traditional (PP and PSOE) and new (Vox and Unidas Podemos) on each end of the political spectrum. The double-key shape of the network is related to the presence of two bridges: that which mediates between the two large blocks and, in each one, the links between traditional and new parties. The lesser development of the traditional right-wing block indicates that it has less substantivity of its own community terms.

Interestingly, the overview of Figure 2 shows how the nexus between the two large poles is predominantly triangles (centre-right) and circles (centre-left). Therefore, agents with diverse and less polarised audiences are preferred by supporters of Spain’s two-party system. But who are the agents at the centre of the network, bridging the gap? In order to answer this question, the same network was used, but this time the nodes were assigned a colour according to the type of communication agent. Figure 3 indicates that it was the traditional media that predominated in this centre of convergence between opposite poles. In other words, these media outlets are those that are used simultaneously and most assiduously by individuals from across the political spectrum. Although they may have disparate political orientations, the media outlets that appear in the centre of Figure 3 continue to play a role characteristic of mass communication culture. That is, less as a source of reinforcement of ideological positions and more as a source of information.

On the other hand, it is interesting that traditional journalists or opinion leaders occupy a bridging position, not between the two main poles, but between the political parties present at each pole (between the two parties on the right and the two parties on the left). Therefore, with the exception of some who occupy more central positions, these opinion leaders appear to be located at one pole or the other, but with no clear affiliation; their niche is more ideological than partisan. Finally, a clear partisan bias can be observed in politicians and digital leaders. Specifically, these agents are those who give our network a bone or double-key shape. However, it is important to note that the agents who occupy the most polarised positions are by far the opinion leaders closest to the new parties (Unidas Podemos bottom left and Vox bottom right).

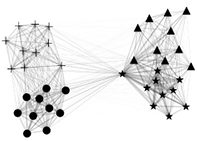

Phase 5: Duplication by type of agent

Duplication networks were used in order to delve deeper into these regularities, but this time they were filtered by type of agent, taking into consideration only the 10 most important nodes in terms of audience for each partisan fraction of the sample. Additionally, we calculated the E-I indexes with the left-right axis, according to the clustering proposed prior in Figure 1 and the Isolation Index for each category. This detailed analysis demonstrated that each type of agent presented a different exposure pattern. Firstly, the media outlets were separated into traditional and digital media, according to the criteria specified. There was barely any evidence of a bipolar structure in the traditional media. A strong cohesion was present between the media, with a political orientation that was predominantly leaning towards either PSOE or PP. On the other hand, a bipolar structure was already evident in the digital media network, in addition to the presence of predominantly circles and stars nodes. This was evidence of the alignment between the alternative parties and the digital media. As regards the previous network, a certain centre and periphery structure could be detected: a few nodes appeared very well connected, the most popular and centred, while a periphery was displayed around them, which in the case of digital media presented a more accentuated bipolarity.

In the case of digital opinion leaders, polarisation was much more evident: in this network there was no longer a populated centre. There were journalists who, as a result of their significant popularity, were closer to the opposite poles, presenting a large number of “co-follows”. Additionally, as we had anticipated, no significant partisan division in the respective poles was found. Lastly, both significant bipolarity and a grouping between political parties in the network of political and opinion leaders could be observed.

The aim of this paper was to analyse the ways in which the extent and degree of polarisation and echo chambers in online public discussions is closely related to the structure and roles of the agents participating in the information environment. In this paper we introduced a yet little-explored variable in the study of the processes of degeneration in political communication: the role of digital native agents (digital leaders and digital media) and those who have traditionally occupied the political space (mass media, political leaders and journalists). Our research question was based on citizens’ access to diverse or related sources of information. In line with previous studies, we have aimed to study whether, in a media environment in which different actors try to spread their messages, citizens mainly consume those that are in line with their own ideology or, on the contrary, they are open to non-related sources.

Our analysis has shown that the answer to this question must be nuanced. As expected, not all agents generated the same type of adherence. Traditional media agents, the mass media, are resources shared by citizens from a plural ideological spectrum. Not only are they predominantly positioned at the centre of Figure 3, but when the duplication by agents is analysed (Table 1), there are no clearly distinguishable poles. On the contrary, the main traditional media agents have both shared and heterogeneous audiences. At the opposite pole, we can observe digital leaders, agents that are followed, mostly or exclusively, by citizens who not only share ideological positions but also partisan affinity.

We therefore consider that four strategies of information source consumption could be established in the information environment analysed. The first of them, characteristic of mass media contexts, is based on the consumption of news and, therefore, is ideologically charged. This consumption is shared by people with diverse ideological positions and would call into question the thesis of selective or similar consumption on social networks, as highlighted in the theoretical framework of this paper. Secondly, there is a consumption of information linked to the new media that is markedly more ideologised than the present one in traditional media. Duplication networks and polarisation values demonstrate that, despite the existence of a significant interrelation, there are in fact some media outlets with clearly partisan audiences. Thus, some of these new digital media are used because they generate politically-related media coverage.

However, upon moving from organisations to subjects, from media outlets—whether traditional or digital—to politicians, journalists or digital leaders—, there was a change in content consumption and exposure to content. Political and media leaders (whether journalists or digital leaders) are followed, to a greater extent, with the aim of strengthening the starting points of citizens. This is evident in the clearly partisan bias of their audiences, ultimately suggesting both selective exposure and avoidance. If so, their communicative strategies are highly successful, as they attract the attention of those who seek to improve both their positions and starting points. This distinction between organisations and individuals leads us to consider a nuance to the perspectives of selective exposure; while information can circulate through the networks, what is relevant in terms of understanding the processes of polarisation and echo chambers could be the way in which that information is received, developed and interpreted within a social group, with the aforementioned leaders as key actors in this process.

As regards the different leaders we have considered, it was to be expected that political leaders would occupy a similar position, i.e., that their “followers” would be aligned with the politician’s ideology. However, it is interesting to note the position of journalists acting as a bridge between the parties at each end of the ideological spectrum. The position of this type of agents is very much polarised but centred; they are ideologically situated to the right or to the left, but without clearly positioning themselves around a specific party. Unlike some digital leaders, journalists put forward ideological opinions that are followed by people who share their same political position, but without clearly taking a stance in support of a specific party. For their part, digital leaders such as “influencers”, “YouTubers”, etc., have a more extreme ideological position.

This being so, we can consider that the plurality of information consumption in digital spaces also generates an important heterogeneity of information consumption habits. More focused when it comes from traditional media, more ideological when the information originates from political leaders or journalists is consumed and, definitely, much more polarised when it is created by new leaders born from digital environments. This plurality of ways of accessing information delivers key insights into interpreting the processes of polarisation and echo chambers. As indicated by our results, it seems that polarisation and echo chambers are related to information acquisition processes arising from digital spaces. Thus, while traditional media and actors maintain a certain degree of centrality, “influencers” or “YouTubers” are references for more partisan positions.

This paper has enabled us to further our understanding of the polarisation and echo chamber processes that take place in online political debates. Unlike previous studies, our study has made it possible to qualify some conclusions that are still open to debate. Firstly, we have observed that there are significant differences in terms of how polarisation processes are configured, depending on the different types of actors in the information environment. Finally, we have seen how polarisation could be more related to opinion than mere information, which consequently leads us to question the importance of selective exposure. Thus, we consider that it would be fruitful to shift the focus from exposure or selective (dis)connection to the group and affective dimension of polarisation.

Adamic, Lada A. and Glance, Natalie (2005). The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 US Election: Divided they Blog. In: Proceedings of the 3rd international workshop on Link discovery (pp. 36-43).

Aelst, Peter van; Strömbäck, Jesper; Aalberg, Toril; Esser, Frank; De Vreese, Claes; Matthes, Jörg; Hopmann, David; Salgado, Susana; Hubé, Nicolas; Stępińska, Agnieszka; Papathanassopoulos, Stylianos; Berganza, Rosa; Legnante, Guido; Reinemann, Carsten; Sheafer, Tamir and Stanyer, James (2017). “Political Communication in a High-choice media Environment: a Challenge for Democracy?”. Annals of the International Communication Association, 41(1): 3-27.

Aragón, Pablo; Kappler, Karolin Eva; Kaltenbrunner, Andreas; Laniado, David and Volkovich, Yana (2013). “Communication Dynamics in Twitter during Political Campaigns: The Case of the 2011 Spanish National Election”. Policy & internet, 5(2): 183-206.

Bakshy, Eytan; Messing, Solomon and Adamic, Lada A. (2015). “Exposure to Ideologically Diverse News and Opinion on Facebook”. Science, 348(6239): 1130-1132.

Barberá, Pablo; Jost, John T.; Nagler, Jonathan; Tucker, Joshua A. and Bonneau, Richard (2015). “Tweeting from Left to Right: Is Online Political Communication more than an Echo Chamber?”. Psychological science, 26(10): 1531-1542.

Bastos, Marco T. and Mercea, Dan (2016). “Serial Activists: Political Twitter beyond Influentials and the Twittertariat”. New Media & Society, 18(10): 2359-2378.

Bruns, Axel (2017). Echo Chamber? What Echo Chamber? Reviewing the Evidence. In: 6th Biennial Future of Journalism Conference (FOJ17).

Cinelli, Matteo; De Francisci Morales, Gianmarco; Galeazzi, Alessandro; Quattrociocchi, Walter and Starnini, Michele (2021). “The Echo Chamber Effect on Social Media”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(9): e2023301118.

Conover, Michael; Gonçalves, Bruno; Flammini, Alessandro and Menczez, Filippo (2012). “Partisan Asymmetries in Online Political Activity”. EPJ Data Science, 1(6): 1-19.

Dahlgren, Peter M. (2022). “Forced versus Selective Exposure: Threatening Messages Lead to Anger but not Dislike of Political Opponents”. Journal of Media Psychology: Theories, Methods, and Applications, 34(3): 150.

Dokuka, Sofia; Koltcov, Sergei; Koltsova, Olessia and Koltsov, Maxim (2018). Echo Chambers vs Opinion Crossroads in News Consumption on Social Media. In: International Conference on Analysis of Images, Social Networks and Texts (pp. 13-19).

Dubois, Elizabeth and Gaffney, Devin (2014). “The Multiple Facets of Influence: Identifying Political Influentials and Opinion Leaders on Twitter”. American behavioral scientist, 58(10): 1260-1277.

Festinger, Leon (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (Vol. 2). California: Stanford university press.

Garimella, Kiran; De Francisci Morales, Gianmarco; Gionis, Aristides and Mathioudakis, Michael (2018). Political Discourse on Social Media: Echo Chambers, Gatekeepers, and the Price of Bipartisanship. In: Proceedings of the 2018 world wide web conference, (pp. 913-922).

Garrett, R. Kelly (2009). “Echo Chambers Online?: Politically Motivated Selective Exposure among Internet News Users”. Journal of computer-mediated communication, 14(2): 265-285.

Garrett, R. Kelly; Carnahan, Dustin and Lynch, Emily K. (2013). “A Turn toward Avoidance? Selective Exposure to Online Political Information, 2004-2008”. Political Behavior, 35(1): 113-134.

Geiß, Stefan; Magin, Melanie; Jürgens, Pascal and Stark, Birgit (2021). “Loopholes in the Echo Chambers: How the Echo Chamber Metaphor Oversimplifies the Effects of Information Gateways on Opinion Expression”. Digital Journalism, 9(5): 660-686.

Gentzkow, Matthew and Shapiro, Jesse M. (2011). “Ideological Segregation Online and Offline”. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4): 1799-1839.

Grömping, Max (2014). “‘Echo Chambers’ Partisan Facebook Groups during the 2014 Thai Election”. Asia Pacific Media Educator, 24(1): 39-59.

Habermas, Jurgen (1991). The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT press.

Hacker, Kenneth L. and Dijk, Jan van (2000). Digital Democracy: Issues of Theory and Practice. New York: Sage Publishing.

Hopkins, Daniel J. and McDonald Ladd, Jonathan (2013). “The Consequences of Broader Media Choice: Evidence from the Expansion of Fox News”. SSRN 2070596.

Iyengar, Shanto; Sood, Gaurav and Lelkes, Yphtach (2012). “Affect, Not Ideologya Social Identity Perspective on Polarization”. Public opinion quarterly, 76(3): 405-431.

Johnson, Thomas J.; Bichard, Shannon L. and Zhang, Weiwu (2009). “Communication communities or ‘cyberghettos?’: A Path Analysis Model Examining Factors that Explain Selective Exposure to Blogs”. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15(1): 60-82.

Klapper, Joseph T. (1960). The Effects of Mass Communication. New York: Free Press.

Lee, Francis; Hai Liang, LF and KY Tang, Gary (2019). “Online Incivility, Cyberbalkanization, and the Dynamics of Opinion Polarization during and after a Mass Protest Event”. International Journal of Communication, 13: 20.

Light, Ben (2014). Disconnecting with Social Networking Sites. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

McPherson, Miller; Smith-Lovin, Lynn and Cook, James M. (2001). “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks”. Annual review of sociology, 27: 415-444.

Merten, Lisa (2021). “Block, Hide or Follow–personal News Curation Practices on Social Media”. Digital Journalism, 9(8): 1018-1039.

Metzger, Miriam J.; Hartsell, Ethan H. and Flanagin, Andrew J. (2020). “Cognitive Dissonance or Credibility? A Comparison of Two Theoretical Explanations for Selective Exposure to Partisan News”. Communication Research, 47(1): 3-28.

Molyneux, Logan (2015). “What Journalists Retweet: Opinion, Humor, and Brand Development on Twitter”. Journalism, 16(7): 920-935.

Müller, Philipp and Schulz, Anne (2021). “Alternative Media for a Populist Audience? Exploring Political and Media Use Predictors of Exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co.”. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2): 277-293. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2019.1646778

Mutz, Diana C. (2002). “Cross-cutting Social Networks: Testing Democratic Theory in Practice”. American Political Science Review, 96(1): 111-126.

Negredo, Samuel; Martínez-Costa, María-Pilar; Breiner, James and Salaverría, Ramón (2020). “Journalism Expands in Spite of the Crisis: Digital-native News Media in Spain”. Media and communication, 8(2): 73-85.

Pariser, Eli (2012). The Filter Bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding From You. London: Penguin.

Parmelee, John H. and Roman, Nataliya (2020). “Insta-echoes: Selective Exposure and Selective Avoidance on Instagram”. Telematics and Informatics, 52: 101432. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101432

Peterson, Erik; Goel, Sharad and Iyengar, Shanto (2021). “Partisan Selective Exposure in Online News Consumption: Evidence from the 2016 Presidential Campaign”. Political science research and methods, 9(2): 242-258.

Prior, Markus (2005). “News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political knowledge and Turnout”. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3): 577-592.

Quattrociocchi, Walter; Scala, Antonio and Sunstein, Cass R. (2016). “Echo Chambers on Facebook”. SSRN 2795110.

Robles, José Manuel; Atienza, Julia; Gómez, Daniel and Guevara, Juan Antonio (2019). “La polarización de ‘La Manada’: el debate público en España y los riesgos de la comunicación política digital”. Tempo Social, 31(3): 193-216. doi: 10.11606/0103-2070.ts.2019.159680

Skovsgaard, Morten; Shehata, Adam and Strömbäck, Jesper (2016). “Opportunity Structures for Selective Exposure: Investigating Selective Exposure and Learning in Swedish Election Campaigns Using Panel Survey Data”. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 21(4): 527-546. doi: 10.1177/1940161216658157

Spohr, Dominic (2017). “Fake News and Ideological Polarization: Filter Bubbles and Selective Exposure on Social Media”. Business information review, 34(3): 150-160.

Stroud, Natalie Jomini (2008). “Media Use and Political Predispositions: Revisiting the Concept of Selective Exposure”. Political Behavior, 30(3): 341-366.

Stroud, Natalie Jomini (2017). 531Selective Exposure Theories. In: The Oxford Handbook of Political Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sunstein, Cass R. (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Terren, Ludovic and Borge-Bravo, Rosa (2021). “Echo Chambers on Social Media: a Systematic Review of the Literature”. Review of Communication Research, 9: 99-118.

Thorson, Kjerstin and Wells, Chris (2016). “Curated Flows: A Framework for Mapping Media Exposure in the Digital Age”. Communication Theory, 26(3): 309-328. doi: 10.1111/comt.12087

Valle, Marc Esteve del and Borge Bravo, Rosa (2018). “Echo Chambers in Parliamentary Twitter Networks: The Catalan Case”. International journal of communication, 12: 21.

Webster, James G. (2005). “Beneath the Veneer of Fragmentation: Television Audience Polarization in a multichannel World”. Journal of Communication, 55(2): 366-382.

Webster, James G. and Ksiazek, Thomas B. (2012). “The Dynamics of Audience Fragmentation: Public Attention in an Age of Digital Media”. Journal of Communication, 62(1): 39-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01616.x

Weeks, Brian E.; Ksiazek, Thomas B. and Holbert, R. Lance (2016). “Partisan Enclaves or Shared Media Experiences? A Network Approach to Understanding Citizens’ political News Environments”. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 60(2): 248-268.

Williams, Hywel TP; McMurray, James R.; Kurz, Tim and Lambert, F. Hugo (2015). “Network Analysis Reveals open Forums and Echo Chambers in Social Media Discussions of Climate Change”. Global environmental change, 32: 126-138.