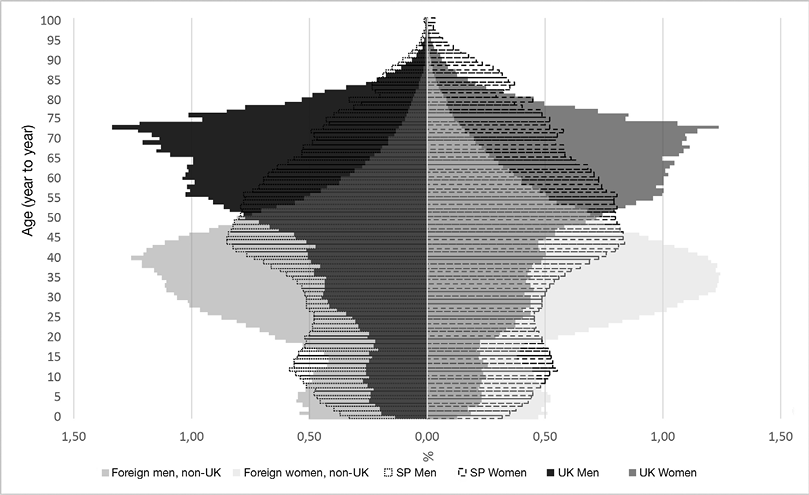

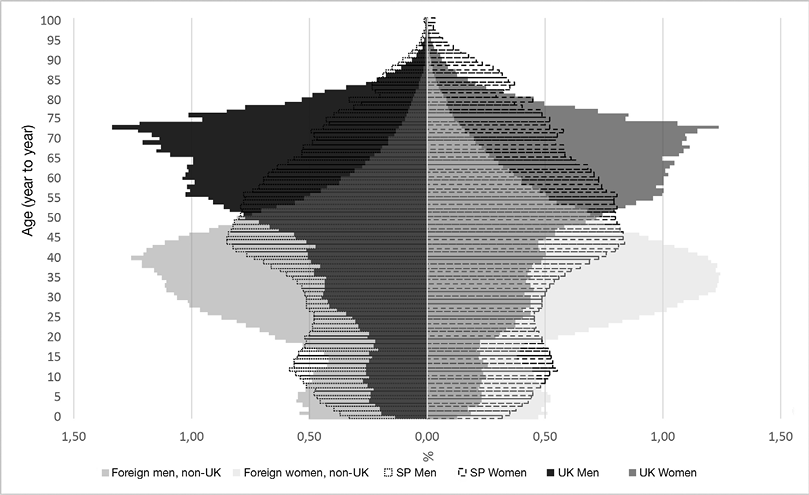

Figure 1. British, Spanish and foreign (non-British) population pyramids, 2021

Source: INE, Continuous Registry Statistics.

doi:10.5477/cis/reis.191.43-62

The Impact of Brexit on The Mobility of Older British Residents in Spain

El impacto del Brexit en la movilidad de los residentes británicos mayores

en España

Raquel Huete, Jordi Giner-Monfort, Alejandro Mantecón, Kelly Hall

and Raquel Gil-Monllor

|

Key words Brexit

|

Abstract This study examines the impact of Brexit on the residential mobility of British residents aged 55 and over in Spain. It focuses on changes in their residential patterns and transnational lifestyles. Using a methodological approach which combines quantitative analysis of population registers and a survey along with qualitative interviews, a change in the daily lives of this demographic group is identified. However, there is no significant evidence of a return to the UK. The results indicate a clear separation between registered and unregistered individuals, which has been exacerbated by new post-Brexit legislation. Furthermore, the gender dimension is emphasised as a critical factor. Women, especially those who have taken on transnational caregiving roles, encounter specific challenges that alter their life projects. |

|

Palabras clave Brexit

|

Resumen Este estudio aborda la incidencia del Brexit en la cohorte de residentes británicos de cincuenta y cinco años y más en España, enfocándose en las alteraciones de sus pautas residenciales y estilos de vida transnacionales. Mediante un enfoque metodológico que combina el análisis cuantitativo de registros poblacionales y una encuesta junto con entrevistas cualitativas, se identifica una alteración en la cotidianidad de este grupo demográfico, aunque no se evidencia un retorno significativo al Reino Unido. Los resultados señalan una marcada separación entre personas empadronadas y no empadronadas, exacerbada por la nueva legislación posbrexit. Además, se destaca la dimensión de género como un factor crucial, donde las mujeres, particularmente aquellas que han asumido roles de cuidadoras transnacionales, enfrentan desafíos específicos que reconfiguran sus proyectos vitales. |

Citation

Huete, Raquel; Giner-Monfort, Jordi; Mantecón, Alejandro; Hall, Kelly; Gil-Monllor, Raquel (2025). “The Impact of Brexit on The Mobility of Older British Residents in Spain”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 191: 43-62. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.191.43-62)

Raquel Huete: Universidad de Alicante | r.huete@ua.es

Jordi Giner-Monfort: Universitat de València | jordi.giner@uv.es

Alejandro Mantecón: Universidad de Alicante | alejandro.mantecon@ua.es

Kelly Hall: University of Birmingham | k.j.hall@bham.ac.uk

Raquel Gil-Monllor: Universidad de Alicante | raquel.gil1@ua.es

Introduction1

The British population is the fifth largest foreign nationality in Spain (INE, 2024). This group of migrants comes seeking a better life through the consumption of leisure experiences in safe environments, attaining a standard of living that is favorable to their purchasing power and is well valued from a climatological point of view as well as in terms of access to leisure, health and transport infrastructures (Huete 2009; O’Reilly, 2000; Rodríguez, 2008). In this way, it differs from other migratory movements having labor motivations.

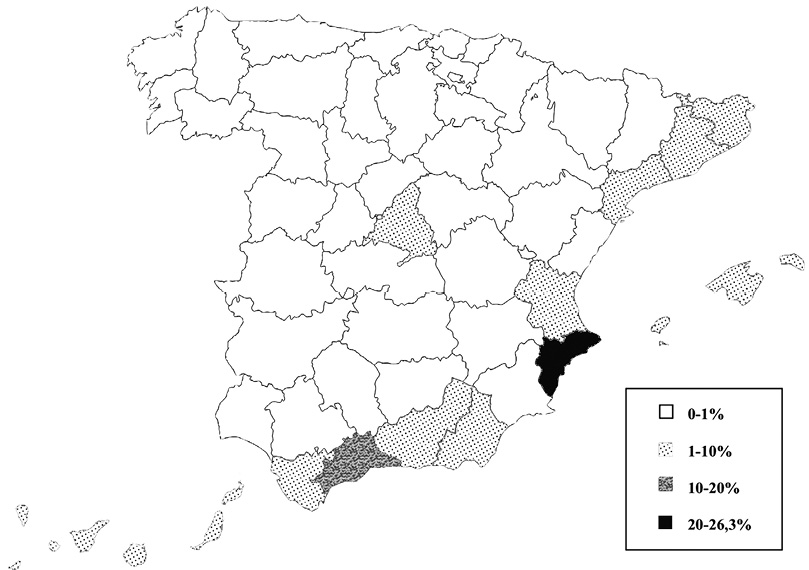

The mobility of British citizens to Spain is integrated in a complex residential system in which the boundaries between migration and tourism are often blurred (López de Lera, 1995; Rodes and Rodríguez, 2021). The consequences of the British presence are clearly evident in the southern and southeastern regions of this country, where most of this population lives (OPI-SGAM, 2024). This is where many British migrants aged fifty-five and over are concentrated, accounting for 58 % of all Britons living in this country (INE, 2024). Therefore, in provinces such as Alicante or Malaga, society is intensely influenced by their ways of life (Huete and Mantecón, 2012; Simó-Noguera, Herzog and Fleerackers, 2013).

Within this context, Brexit burst into the scene in 2016, altering relations between the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK), with varying effects being seen between some countries and others depending on the established links (Benson and O’Reilly, 2022). In the south of Spain, Brexit caused great uncertainty in the residential dynamics. It has affected the evolution of real estate markets, the demand for care in public and private healthcare and the financing needs of local administrations (Giner-Monfort and Huete, 2021; O’Reilly, 2020).

The objectives of this work are the following: a) to assess the impact of Brexit on the decision to return to the UK by British residents aged fifty-five and over who reside in Spain; and b) to attempt to understand how the British resident from the aforementioned age group interpret the influence of Brexit on their residential projects.

These issues deserve to be investigated. Their repercussions are essential to understanding the transformations taking place in Spanish society, especially with regard to the changes that Brexit is producing with respect to the residential mobility systems of the Mediterranean regions. The proposed analysis seeks to clarify the reconfiguration of a context in which social actors with diverse interests are involved.

Brexit as a determinant

of transnational lifestyles

The British population residing in Spain is characterized by the following: a) its large size (for years now it has been the third largest foreign collective in the country), b) being one of the groups having the oldest mean age (in the compared age and sex pyramid –Figure 1– differences with the Spanish population and the other nationalities are evidenced), c) its high spatial concentration around the provinces of Alicante and Malaga, spreading from these provinces to other regions of the Mediterranean strip2 (clear concentration in the fifty-five and older age group) and d) being a predominantly retired population, with 9.9 % of the active population among residents aged fifty-five and over, as compared to 23.9 % among Spaniards in that same age group. As for educational level, 55 % of British people aged fifty-five or over have primary school education and 25 % received higher education, as compared to 30 % and 16 % in the Spanish population.

According to the existing literature, it is understood that the British population aged fifty-five and older residing in Spain constitutes a migratory group characterized by the predominance of motivations that are more closely related to consumption than to production (Huete, 2009; Rodríguez, Lardiés and Rodríguez, 2010). Their relationship with the local populations tends to be conditioned by their limited Spanish language skills and their daily lifestyle, which is focused on a dense associative network, formed with their compatriots (O’Reilly, 2009; Olsson and O’Reilly, 2017; Simó-Noguera, Herzog and Fleerackers, 2013).

The residential links and strategies that they establish outside of their country give rise to a variety of biographical projects, in which the number of days spent in Spain each year fluctuates depending on the life stage, family circumstances and changing social context. In addition to tourism activity, a diversity of cases can be recognized which range between situations of permanent and semi-permanent residence (Huete, 2009; Huete and Mantecón, 2012; Rodes and Rodríguez, 2021).

To offer a more comprehensive perspective of these realities, John Urry (2007) developed a new explanatory paradigm capable of transcending the usual theoretical schemes, in which tourism and migration tend to be considered separate categories within which a multitude of typologies are identified. Urry advocated the usefulness of conceiving the different forms of mobility, with their temporal and spatial specificities, as part of a continuum of unstable situations influenced by a complexity of psychosocial, economic, cultural, political and environmental factors. He suggested that the voluntariness of the displacement, the influence of material versus immaterial aspects and the relationship between individual and structural reasons only makes sense if we assume that reality extends beyond these types of approaches. This requires an epistemological reorientation, as already mentioned for the study of return migrations (Ruben, Houte and Davids, 2009). Therefore, authors such as De Haas (2014) and Piguet (2018) emphasized the need to promote research that analyzes how expectations of improved quality of life which are found in diverse displacements may be modulated by gender relations, moral commitments or emotional ties established with different places at the same time, taking into account that these elements are sensitive to broader social changes.

Brexit redefines the rules governing the possibilities of carrying out a transnational lifestyle. The impact of the so-called 90/180-day rule is of special interest in this respect. In December of 2020, the Spanish Official State Gazette (BOE) published Royal Decree-Law 38/2020 approving measures to adapt the UK of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the status of third state following the end of the transitional period provided for in the Agreement on its withdrawal from the EU (BOE, 2020). According to the new legal framework, as of 1 January 2021, nationals of the UK who travel to the EU and the Schengen area will be treated as third-country nationals and are therefore subject to controls at the Schengen area borders. This implies that stays in the EU states cannot exceed ninety days (not necessarily consecutive) in any 180-day period, considering the Schengen area to be an integrated area of free mobility and, therefore, applying the rule on a supranational scale. So, it does not matter which country is the source of entry into the Schengen area for the days of possible stay to begin to be counted. In the simplest situation, it may be summed up by saying that after spending three full months in Spanish territory, it is necessary to leave the Schengen area and wait another three months before re-entering. Violation of this rule places the person in an irregular situation, exposing him/her to economic sanctions or, in exceptional cases, to an expulsion process. The rule applies equally to those who own real estate, although if their property was acquired after 2014 for a value of at least five hundred thousand euros, the procedures for requesting a residence permit are facilitated by acquiring the Golden Visa. For this visa, the basic renewal requirements are to maintain the initial investment and visit Spain at least once a year (BOE, 2013). This path encourages the acceptance of a privileged class in an international setting (Holleran, 2021).

Given this situation, uncertainty is on the rise regarding the reaction of British residents and, especially, with respect to abandoning their life project in Spain. The option of returning to the UK would be justified by the sense that the obligations derived from staying in Spain, as well as the rights in their country of origin, are becoming blurred (Giner-Monfort and Huete, 2021; Giner-Monfort and Hall, 2024). Application of the 90/180-day rule may be incompatible with the maintenance of certain transnational lifestyles.

As a guiding hypothesis for the research, it is suggested that the scenario derived from Brexit may favor an increase in return migrations of Britons aged fifty-five and older, and at the same time, an increase may be seen in both their direct intentions and their return plans.

To determine the extent to which Brexit has caused the return of British residents, a quantitative methodology is proposed using two distinct approaches. On the one hand, there is the Residential Variation Statistic (EVR), which was created by the National Statistics Institute based on changes in the census registry due to change of address. Access to the microdata from this source allows us to observe people who arrive from abroad and those who emigrate to other countries, in addition to the variables of age, sex, territory of origin and destination. The reliability of this source has been questioned, especially for the British community, which has historically been reluctant to register. During the 2012-2014 period, a purge took place which affected the European communities (including the British one), raising doubts as to their reliability (González-Ferrer and Moreno-Fuentes, 2017). But the legislative changes resulting from the Brexit may have modified this situation. Since 2020, with the end of the Withdrawal Agreement, there has been an increasing interest in registering among those residing in Spanish territory, even by those who had not registered prior to Brexit coming into force. Thus, the departures of the British population in the EVR have been analyzed from 2016 to 2021. This analysis results in a file with seventeen columns (one for each variable, including age, sex, nationality, etc.) and 120 274 lines, (one line for each departure made by a British citizen abroad). If only considering those aged fifty-five and over, there are 65 249 lines.

On the other hand, a self-completed electronic questionnaire has been designed. This technique is being increasingly used to investigate populations (such as the one discussed here) having a high permeability to new technologies due to their transnational nature (Díaz de Rada, Domínguez and Pasadas, 2019). The URL link was distributed via different channels to attain a sufficiently large response base: social networks, British organizations, opinion leaders and advertisements in the English press published in Spain. A total of 826 responses were collected from British nationals residing in Spain. In this work, the 643 responses corresponding to individuals aged fifty-five or older have been analyzed3. Questions focused on potential causes triggering a return, the impact of Brexit and COVID-19, and other return-related issues explored in previous analyses that required follow up. The survey took place over a month and a half during 2020. Assuming that it represented a population of 145 800 British people aged fifty-five and over who resided in Spain at the time, its margin of error would be 3.9 % in an assumed P=Q=0.5, with a confidence level of 2σ. Table 1 presents data on the sample4.

To delve deeper into the meanings given by Britons aged fifty-five or over with respect to the impact of Brexit on their residential projects, a qualitative approach based on the application of semi-structured interviews has been followed. A flexible script with common themes is proposed, although during the interviews, certain questions have been interspersed to better understand the arguments developed in each case. The following are some of the common themes: their reasons for moving to Spain; a description of their experience in the country; a comparison between their life in the UK and their life in Spain; an assessment of the changes that have taken place in their life (and in their self-perception) as a result of this move; a description of their family life; an explanation and assessment of their social relationships; the influence of gender on their residential experience; the effects of COVID-19 on their transnational project; and the effects or potential effects of Brexit on their lives, paying special attention to its possible impact on their residential plans. This text focuses on the arguments expressed regarding the effects of Brexit, with the previously addressed topics serving as facilitators of a reflection that leads to an assessment of what is considered to be the essential question.

The sample was selected by snowball sampling, guided by the search for the profile under study. The initial contacts were six British members of distinct foreign resident associations in different municipalities (coastal and inland) of the Alicante province. Thanks to these contacts, the first interviewees were found. Subsequently, various interview chains were created, avoiding the risk of falling into group encapsulation dynamics that would create an overly homogeneous sample. The province of Alicante was the focus of the qualitative part of the study for practical reasons. The research team understood that the existing literature confirms that the attitudes and behaviors of British people aged fifty-five and over who have settled more or less permanently in this region are typologically representative of the lifestyles of members of this group in many other Mediterranean locations (Gustafson, 2009; King, Warnes and Williams, 2000; Rodríguez, Lardiés and Rodríguez, 2010).

The interviews were conducted between March and October of 2022 in cafeterias, cultural centers, city halls and homes. They were conducted in English by a bilingual team of interviewers. After guaranteeing the participants’ anonymity and requesting permission, all interviews were recorded. The average duration of the interviews was fifty-three minutes. The transcribed textual material was reordered according to the topics discussed, gender and residential location of the interviewees. This was followed by a stage of successive readings, accompanied by notes that systematically characterize the interviewees’ assessments for each topic, associating ideas and checking reasoning, until recognizing lines of argument. This procedure responds to the general logic of qualitative analysis and is repeated until patterns of discursive regularity are found (Conde, 2009). Following the recommendations of Miles and Huberman (1994) with respect to the need to establish internal verification procedures in qualitative analyses, all of the research team members went over the consistency of the identified topics and their potential interpretations several times, until agreeing on a final report.

The sample size has been determined using the principle of discursive saturation for the main topics addressed: upon reaching the thirty-fifth interview, it is found that the information collected in the last interviews is redundant and that there is a very low probability of encountering new arguments. Therefore, the fieldwork comes to an end. This sample consists of eighteen women and seventeen men, having a mean age of 69.3 years.

Illustrative fragments are included in the presentation of the results to facilitate the understanding of the identified discourse. Because this is a qualitative study, statistical representativeness is not a goal. The selected fragments were translated into Spanish by the authors.

The effect of Brexit

on residential mobility:

a quantitative approach

Analysis of the census registry leaves little doubt about the movement of the British population following the approval of Brexit. After 2016, the number of registered residents continued to grow (see Table 3). In the period under study, the population rate only declined in 2016, which should be understood as the continuation of a prior period (2012-2015) during which tens of thousands of registered residents who had not confirmed their residence in Spain were deregistered. The increase taking place between 2020 and 2021 may be interpreted as the result of migrations, but also as the consequence of regularizations made by individuals living in Spain without being registered there. It should be noted that they can only stay for a maximum of one hundred and eighty days per year, regardless of their status as homeowners or tenants. Thus, it is worth noting that the British are the foreign group that has purchased the most homes in Spain over recent years (Álvarez, Blanco and García-Posada, 2020). The increases taking place in 2021 and 2022 may be attributed to new registrations, either through Golden Visas, or non-lucrative visas (between 2020 and June of 2023, a total of 35 675 residence permits were issued to British citizens by via this channel, 66 % only in 2020). However, a portion of the registrations from 2021 may still fall under the conditions stipulated by the Withdrawal Agreement (i.e. individuals demonstrating their residence in Spain before 31 December 2020).

Table 3. British nationals in the census registry (2016-2022)

|

Year |

N |

N+1-N |

|

2016 |

256,501 |

-15,716 |

|

2017 |

240,785 |

149 |

|

2018 |

242,837 |

2,052 |

|

2019 |

250,392 |

7,555 |

|

2020 |

262,885 |

12,493 |

|

2021 |

282,124 |

19,239 |

|

2022 |

293,171 |

11,047 |

Source: INE, Continuous Registry Statistics.

The EVR data allow us to analyze the returns produced by voluntary withdrawal from the census registry or from administrative removal. The former are the least numerous, since it requires that the individual actively request removal from the system. There is no clear motivation for this (for example, being a requirement for subsequent registration in the UK). On the other hand, the second group is larger since the removal is processed by the administration itself when verifying that the residence permit has not been renewed. Therefore, the number of removals taking place during the study period reached 126 198, of which 68 531 correspond to individuals aged fifty-five and over. Only 9.9 % of these removals were registered as returns to the UK, 10.1 % when considering the data from the population aged fifty-five and over. Portugal, France and the United States are the main destinations of the few re-emigrations registered during this period. This would mean that the post-retirement migration experience would continue in third countries having characteristics similar to Spain (at least Portugal and France, with respect to climate and reception of the British population).

Therefore, the annual return or exit rate (returns from the total population) would be between 5 and 6.5 per 100 British residents, with the exception of 2016 and 2017, when it was 11.6 and 12.1. This does not appear to be a very high rate, although the difficulty in controlling a group with a marked transnational character, together with the limitations of the Spanish registration system, hinders estimation making.

Regarding British women, registry data show percentages below 50 % of the total returns, although the variations by gender are small and barely distinguish between different behaviors, except for a reduction in the return of women over the age of 85 as compared to men of that age (see Table 5).

In order to better understand the reality of the British community, a survey was conducted to estimate the following: a) direct intent to return to the UK; and b) the future expectation to return. Regarding the question of whether they had considered returning to the UK, 87.4 % confessed that they had not planned to, although when asking about the future, 42.6 % affirmed that it is something that may happen, while 5.8 % said that it is a step that they have already planned in their migration process. With regard to the direct intention to return as collected from the survey, the differences are not statistically significant when comparing the responses of men and women (χ²=5.142; df=3; sig=0.162). However, in the future return forecast, significant gender-based differences are observed (χ²=6.086; df=2; sig=0.048), suggesting a greater expectation amongst women as compared to men, something that contradicts that which has been observed for other national groups in which women present a lower intent to return (King and Lulle, 2022).

Considering direct intention to return as a binomial variable (intending or not intending to return to the UK) and comparing it with the survey’s main independent variables (see Table 7), no significant relationship is seen with age, sex, educational level, place of residence, monthly income or even support for Brexit. However, a significant relationship is found with civil status, being or not being registered in Spain and having properties in the UK. The same procedure yields different results, when considering the so-called return forecast, as opposed to direct return intention. The relationships with the variables sex, year of arrival, owning a home in Spain and having knowledge of Spanish are once again significant and marital status is not. Specifically, women reveal a significantly higher future return forecast than men. The same occurs amongst those revealing weaker ties to Spanish society: those that are not registered, those who do not own property in Spain, those having property in the UK and those with less knowledge of the Spanish language.

A likelihood ratio test was carried out for direct intention to return and for expectation to return, including five variables with some a priori relationship with the return and with Brexit as independent variables: being married; not being registered; having a mortgage in Spain; owning a property in the UK; and being happy with the results of the Brexit referendum (see Table 8). For direct intent to return, four of the categories have a significant weight in the improvement of the intersection model over the null model, with the exception of the question about Brexit, such that the model would predict 88.6 % of the result of the dependent variable. As for future return expectation, with just the variables of not being registered in the census registry and owning property in the UK, it was possible to predict 62.1 % of the results of the independent variable. It may be said that ties with the country of origin (and the lack of ties with the host country) are decisive in understanding future return.

The meanings of Brexit from a qualitative perspective

The widening gap between registered and non-registered residents

The dominant discourse, shared by men and women, interprets Brexit as a problematic reality that has a different severity depending on the type of link established with Spain. The interviewed individuals who are both registered and not registered understand that the most disturbing impacts on daily life affect the latter group. Thus, the registered individuals recognize undesirable changes that are perceived as acceptable. They do not significantly modify their social life or the assessment of their migratory experience.

The impact of Brexit has not been as bad as we expected. There are some little things, such as some foods […] But there is no problem with Spanish food, which is great […] But there are some things that… are more difficult to achieve since Brexit. But nothing truly important that we cannot have in Spain (E32).

We do not view ourselves as ex-pats; we consider ourselves immigrants. We came here to live. I suppose it affects us in one or two ways, but nothing major. If our children come to see us, the administrative procedures have changed slightly. But they are not terrible changes. We spend a lot of time helping lots of other Britons for whom Brexit has meant a major change (E13).

However, in the case of non-registered residents, the legislative changes resulting from Brexit have led to a reorganization of their life plans. The application of the 90/180-day rule is the main cause of this. The implications of this regulation have led to problems, and, in addition to their opinion of Brexit, their interests have focused on the legal modifications. In fact, many of the interviewees do not hesitate in being more critical of Brexit than of COVID-19, directing their irritation towards the British, Spanish and European political institutions (focusing the responsibilities on one or the other, depending on the interviewee), whom they accuse of not being involved in finding solutions to their problems. Regarding this, possessing real estate is viewed by this group as a distinctive element that should justify privileged treatment by the administrations.

It has been worse for those of us who own property in Spain and are not registered as residents. We spend less than six months a year here, and there are many people in our situation. I think they have not taken us into account […]. Those of us who live in the UK and own property here would have liked to be given freedom of movement within the Schengen area, to be allowed to stay in Spain for up to six months without changing residence […]. That would be an improvement, but they must have the will to do it. Otherwise, it would be frustrating (E26).

The new situation not only highlights the different administrative status between residents, but it also produces symbolic markers loaded with moral connotations. Thus, the accentuation of administrative differences is accompanied by invisible walls within the British community.

Sometimes they don’t understand our problems, they look at us as if we were illegals […]. Really, it is like a division in our country, and you are on one side or on the other, and here either you are 100 % resident, registered in Spain or you are a part-timer. Those who are registered are very unkind to us since they assume that we are here illegally (E2).

We did all the paperwork and administrative procedures to make sure everything was legal. Taxes, everything. There were people living here who we knew were not doing it, who were hiding it, and who had property in England, Scotland or wherever. They did not declare anything. And they pretended to be registered, and they were not. So now, those are the ones asking for help from organizations, because they are scared. They have been panicking since Brexit, you know. I don’t like them (E32).

The new legislative framework alters the mobility patterns of non-registered residents, but it also impacts on the emotional well-being of the registered individuals, since it interrupts emotional ties or modifies the type of relationship that they can have with their relatives.

My children have decided not to come since Brexit […]. Now they can only stay for ninety days at most; the trip costs them more money and the routes are not the same […]. Normally my children would come to see me, and also friends from England, but over the last two and a half years I have had no one. I feel a bit isolated. Also, many of my friends had a second home here and have sold it (E27).

Both COVID-19 and Brexit have a clearly critical nature, although discursive variations appear. All of the registered individuals referred to the pandemic as the most dramatic crisis. The interviewees stressed its global impact, the deaths caused, the drastic restrictions experienced on mobility and the interruption of recreational activities that structure their lives in Spain. However, as the interview advanced, the same interviewees often experienced an emotional reflectivity process which led them to define the COVID-19 crisis as a dramatic event but one that had taken place in the past. On the other hand, Brexit, although not perceived as a process producing critical impacts on their daily lives, did generate a persistent feeling of disaffection. This feeling is motivated by the permanent nature of Brexit, the distrust of its reversibility over the medium term and, ultimately, by how it questions identity and emotional ties, both with Europe and with their country of origin.

It is just annoying. Because small problems arise, new administrative procedures […]. The country is no longer in the European Union. People simply no longer have European citizenship […]. Everyone is very disappointed, as if our country has let us down. And that means that the bond you had with the country where you were born or lived has been broken. It is almost as if you no longer trust it (E33).

The impact of Brexit (with all of its practical concerns) on the biographical projects of non-registered people tends to overshadow other assessments. This does not mean to suggest that these people have no conflicting feelings about the identity implications of Brexit, although given their immediate concerns, they barely expressed them.

The emotional cost of becoming a long distance grandparent

The different relationship that men and women establish with their children conditions their experience with their country of origin and with Spain.

British men don’t feel as connected to their families […]. I think that men are more motivated than women to live here since the women miss their families more (E35).

When becoming grandmothers, women are more likely than their husbands to question their residential project. The arrival of grandchildren brings to light the different meanings that men and women give to family, as well as the unequal importance that it has compared to other areas of life. This gives rise to different emotional and practical commitments which, ultimately, may lead to the rethinking of one’s lifestyle.

A British woman told me: “Oh, we are going back to England”. And I told her: “Oh, why are you going back?” –“I miss my grandchildren” […]. They believe that their grandchildren are always going to be little kids. Whereas the men think “Well, I have done my time in England, I want to be here”. I think that sometimes it is female sensitivity, this connection that women have with the family, especially with grandchildren […]. Just as I left England, so did my friends. You are dreaming if you think you are going to return to England and find the life that you left there twenty-three years ago (E30).

When asked about the reasons that might redefine their ties with Spain, the interviewees referred to the death of a partner, an unexpected deterioration in their financial or administrative situation, or health problems. Men and women tend to have a common belief about what an unsustainable situation would be with regard to these issues, but the same does not occur with the meanings that they assign to their status as grandparents. The assessment of grandchildren attractors that encourages grandmothers to end or interrupt their residence in Spain contrasts with the lower inclination of men to consider this fact as a justification for questioning their chosen way of life.

The different perception of the practical effects associated with the family bond is inserted in a context which, in the case of men, appears to be a double discourse. A redundant element among the male and female interviewees is an admiration for the importance of the family in Spanish society. They come to this conclusion by regularly observing the presence of individuals of different generations, especially grandparents and grandchildren, in public leisure spaces. This is praised by the Britons as a positive value. At the same time, the interviewees regret that family relationships have weakened in the UK over the last few decades. In line with this definition of the situation, women admit their desire to participate more actively in raising their grandchildren, even if this means ending (or transforming) their life in Spain. However, the same men who admire the close relationship between Spanish grandparents and their grandchildren do not share the same willingness as their wives to modify their lifestyle.

A bit of a disagreement with my daughters. They probably expect me to spend more time in the UK, but they work so much that I would not see them very much anyway […]. The “holidays” in the summer, you don’t have this in the UK. The groups… everyone goes together… In the UK, the custom is to simply stick the old people in nursing homes. Here they are more integrated with their families (E24).

We know a lot of people who left at more or less the same time and ultimately, they have returned to the UK. For their grandchildren, that is probably the most common reason: young daughters who have children and need the grandmother to be there, or the grandmother thinks that they really need to be there […]. We certainly wouldn’t think about returning […]. We love how the Spanish embrace everyone, from babies in the crib to grandparents. They grow up wanting to maintain those traditions. It is something that, in the UK, in most places, has been lost (E34).

In fact, the men’s double discourse expresses: a) their praise of family life and strong intergenerational ties; b) nostalgia for a time gone by when family relationships in the UK were structured by other values; and c) their refusal to change their present situation. It is this last point that marks the difference with the women interviewed. When men weigh the pros and cons, the balance tips towards maintaining their happiness that comes with a lifestyle under the sun.

Becoming grandparents does not create a bifurcation in the meanings assigned by men and women to the family. It is an event which, in the post-employment stage, reveals the ongoing division of roles that is internalized throughout life. Although at this stage of life, men view their role as resource providers as declining. Women, however, continue to affirm their role as family caregivers. The arrival of grandchildren brings about a renewed expression of the implications of this divide.

What British women find most difficult is that when they have grandchildren, women want to spend more time with them, whereas men don’t… That is something that would make a retired British couple return to the UK […]. Traditionally, for men that have worked from 9 to 5… the household is not their responsibility, if they were not responsible for those activities with their children… (E28).

The consequences of the differences between male and female roles are made increasingly evident by Brexit. Restrictions on travel and length of stay make it difficult to carry out transnational biographical projects, where residence becomes a fluid reality, and is not fixed to a specific territory. Following Brexit, and in the absence of a legislative framework that supports this flexibility, many women are unwilling to pay the emotional cost of spending long periods of time away from their families. As the interviewees mention, this cost is much lower in the case of men. From the male perspective, the difficulties faced with respect to seeing their families form part of a series of acceptable inconveniences.

It does not really affect me because I decided to move permanently. I wanted to be here full time, not just ninety days, that’s why I became a resident. However, my children were affected by this ninety-day restriction […]. I think that the people I know who are based here, often the women go back to the UK for longer periods. I think it is mainly for family reasons, because what they miss the most is the family they have in the UK. I always worked when I lived there, so my friends were mainly from work, from social gatherings […]. Once I discovered the advantages of being here, how easy it is to find groups of people, to socialize… that is what you want when you get older (E18).

Brexit is a fundamental event in the recent history of Europe. The full extent of its impact will only be clearly understood in a few years, with the effects varying greatly from one country to another. Regarding Spain, this work presents an approach to understanding how this event has influenced the lifestyles of British citizens aged fifty-five and older, who are permanent or semi-permanent residents of Mediterranean regions. When comparing migration to mere residential mobility, this community is more inclined to base its lifestyle on leisure-based motivations, as opposed to productivity. Their residential strategies and lifestyles condition the dynamics of many towns located in southern Europe and, especially, southern Spain.

As for the possible impact of Brexit on the return of British residents aged fifty-five or over to the UK, the analyzed data do not suggest that it has been a relevant event. In any case, the departures that may have occurred due to Brexit have been offset by new arrivals, with no change in trend being perceived. However, when considering the gender variable, important nuances are evident: men and women return in similar proportions, although women express a greater desire to return in the future. The same occurs with those having weaker bonds with Spain. In order to gain a deeper understanding of these findings that have been identified in the quantitative work, a qualitative study has been conducted on the meanings with which the target population interprets Brexit in relation to their life in Spain. This delves into sociological issues associated with gender and the type of ties that are established by the British.

The post-Brexit context accentuates the difference between registered and non-registered Britons, highlighting the separation between the administrative status of each group and highlighting mutual perceptions that are laden with moral judgements. Respondents take a negative view of the changes resulting from Brexit, although the effects on their lives vary widely. Non-registered Britons view their multi-residential lifestyle as being compromised and they do not understand why home ownership does not provide them with an administrative status similar to that enjoyed by registered Britons. Registered residents, on the other hand, consider the ways in which their social relationships (with friends and family) are affected.

Restrictions on mobility have increased in various ways, and, within this scenario, the gender variable has been found to be decisive. Brexit has amplified the tensions existing between how men and women view their family responsibilities. The difficulties posed by Brexit with respect to the integration of life in Spain within a flexible residential project have led to an increased emotional cost for women. Although statistics do not record different behavior between the two sexes, our research does identify a perception of daily experience conditioned by gender. This is in line with the results obtained with similar populations by Ahmed (2015), Croucher (2014), Dixon (2021) and Lundström and Twine (2011). Becoming grandparents is an event that may cause tension in the couple. Regardless of whether it alters their residential behavior, it makes women question their life plan in Spain. This explanation coincides with other studies on the different feelings of attachment that British residents in Spain express towards their families, especially towards their grandchildren (Hall, Betty and Giner, 2017; Repetti and Calasanti, 2020).

With the arrival of grandchildren in the post-work life stage, the restrictions generated by Brexit may bring to light the effects of a socialization that is structured by gender roles, based on the “male provider” and “female caregiver” dichotomy. On the other hand, the unequal impact of Brexit on the British community favors controversies arising from the aspiration of non-registered Britons to acquire a status that facilitates privileges related to the possession of specific capital (linked to the interests of the real estate business).

Recognition of this situation helps in the understanding of the social dynamics of the British population living in Spain and to the understanding of how Brexit affects the emotional well-being and daily life of groups that are rarely considered by sociological research. The evidence presented also helps to conceptualize new forms of residential mobility. Therefore, it may be interpreted in light of the proposals for theoretical reorientation outlined above (Urry, 2007).

Despite the limitations of this study, its conclusions have implications at an institutional level, given the challenges posed to the management of residential mobility in the EU and the dissemination of the problems affecting the British population. It also has implications with respect to the creation of gender-sensitive public policies. This suggests potential future lines of research considering other national groups having a large presence in Spain and the role of gender in their migratory trajectories.

Ahmed, Anya (2015). Retiring to Spain. Bristol: Policy.

Álvarez, Laura; Blanco, Roberto and García-Posada, Miguel (2020). “La inversión extranjera en el mercado inmobiliario residencial español entre 2007 y 2019”. Boletín Económico/Banco de España, 2/2020. Available at: https://repositorio.bde.es/bitstream/123456789/12381/1/be2002-art14.pdf, acceso 10 de marzo de 2024, access March 10, 2024.

Benson, Michaela and O’Reilly, Karen (2022). “Reflexive Practice in Live Sociology: Lessons from Researching Brexit in the Lives of British Citizens Living in the EU-27”. Qualitative Research, 22(2): 177-193. doi: 10.1177/1468794120977795

Boletín Oficial del Estado (2013). Ley 14/2013, de 27 de septiembre, de apoyo a los emprendedores y su internacionalización. Available at: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2013/BOE-A-2013-10074-consolidado.pdf, access March 8, 2024.

Boletín Oficial del Estado (2020). Real Decreto-ley 38/2020, de 29 de diciembre. Available at: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2020/12/30/pdfs/BOE-A-2020-17266.pdf, access March 8, 2024.

Conde, Fernando (2009). Análisis sociológico del sistema de discursos. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Croucher, Sheila (2014). The Gendered Spatialities of Lifestyle Migration. In: M. Janoschka and H. Haas (eds.). Contested Spatialities, Lifestyle Migration and Residential Tourism. London: Routledge.

De Haas, Heine (2014). Migration Theory. Quo Vadis? International Migration Institute Working Papers. Paper 100, November. Available at: https://www.migrationinstitute.org/publications/wp-100-14, access February 26, 2024.

Díaz de Rada, Vidal; Domínguez, Juan and Pasadas, Sara (2019). Internet como modo de administración de encuestas. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Dixon, Laura (2021). Gender, Sexuality and National Identity in the Lives of British Lifestyle Migrants in Spain. London: Routledge.

Giner-Monfort, Jordi; Hall, Kelly and Betty, Charles (2016). “Back to Brit: Retired British Migrants Returning from Spain”. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(5): 797-815. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1100068

Giner-Monfort, Jordi and Huete, Raquel (2021). “Uncertain Sunset Lives: British Migrants Facing Brexit in Spain”. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(1): 74-79. doi: 10.1177/0969776420972148

Giner-Monfort, Jordi and Hall, Kelly (2024). “Older British Migrants in Spain: Return Patterns and Intentions Post-Brexit”. Population, Space and Place, 30(1): e2730. doi: 10.1002/psp.2730

González-Ferrer, Amparo and Moreno-Fuentes, Francisco (2017). “Back to the Suitcase? Emigration during the Great Recession in Spain”. South European Society and Politics, 22(4): 447-471. doi: 10.1080/13608746.2017.141305

Huete, Raquel (2009). Turistas que llegan para quedarse. Una explicación sociológica sobre la movilidad residencial. Alicante: Universidad de Alicante.

O’Reilly, Karen (2000). The British on the Costa del Sol. London: Routledge.

Simó-Noguera, Carles; Herzog, Benno and Fleerackers, Jolien (2013). “Forms of Social Capital among European Retirement Migrants in the Valencian Community”. Migraciones Internacionales, 7(1): 131-163. doi: 10.17428/rmi.v6i24.712Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity.

Urry, John (2007). Mobilities. Cambridge: Polity.

1 Recognition of the funding of the project: The relationship between quality of life migration and the tourist dynamics of destinations (Ciconia) (PID2020-117459RB-C21), Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.

2 The shapes of the population pyramid and the provincial distribution resemble those existing prior to the 2016 referendum (Giner-Monfort, Hall and Betty, 2016).

3 The comparison of the sample distribution with similar probability samples (subsample of 829 people aged fifty-five and over from the 2021 ECEPOV) offers a similar territorial distribution, although some provinces are underrepresented (Balearic Islands, Las Palmas, Santa Cruz de Tenerife and Murcia) while others are overrepresented (Alicante, Malaga, Almeria, Cadiz, Granada and Valencia). Others fit very well with the observed distribution (Avila, Badajoz, A Coruña, Huesca, Jaen, Lugo, Madrid and Zaragoza). The mean age in the analyzed sample is 67.6 years, as compared to 68.4 in the ECEPOV subsample. Distribution by sex is also similar (47.5 % male in the ECEPOV as compared to 48.1 % in our sample).

4 Regarding education level, this sample reveals different characteristics with respect to those mentioned at the beginning of section 2.

Figure 1. British, Spanish and foreign (non-British) population pyramids, 2021

Source: INE, Continuous Registry Statistics.

Figure 2. Provincial distribution of the British population aged fifty-five and over (percentage of total Britons, 2021)

Source: INE, Continuous Registry Statistics.

Table 1. Survey sample

|

Sex |

48 % women; 52 % men |

|

Mean age |

67.6 years of age |

|

Year of arrival |

44.5 % between 2000 and 2009 |

|

Civil status |

65.8 % married; 13.2 divorced or separated; 11.4 widows/widowers |

|

Education level |

9.1 % primary school education, 53 % secondary education; 37.9 % university studies |

|

Territory |

34.1 % Malaga; 28.8 % Alicante |

|

Place of residence |

34.8 % Scattered; 32.4 % housing developments; 32.9 % city center |

|

Property |

84.3 % property in Spain; 15.7 % rent |

|

Property in UK |

20.1 % property in the UK; 79.9 % do not have property |

|

Knowledge of Spanish |

62.2 % do not speak Spanish fluently; 37.8 % speak Spanish |

|

Household income |

57 % earn less than 2000£/month; 2.3 % up to 500£/month |

|

Agrees with Brexit |

80.6 % no; 19.4 % yes |

Source: The author’s own creation.

Table 2. Sample of qualitative interviews

|

Interviewed |

Gender |

Age |

Registered |

Years in Spain |

|

E1 |

Male |

72 |

Yes |

21 |

|

E2 |

Female |

69 |

No |

20 |

|

E3 |

Female |

81 |

Yes |

30 |

|

E4 |

Female |

69 |

Yes |

20 |

|

E5 |

Female |

77 |

No |

11 |

|

E6 |

Male |

78 |

Yes |

12 |

|

E7 |

Female |

69 |

Yes |

10 |

|

E8 |

Male |

66 |

Yes |

9 |

|

E9 |

Female |

75 |

Yes |

27 |

|

E10 |

Female |

74 |

Yes |

27 |

|

E11 |

Male |

79 |

Yes |

21 |

|

E12 |

Female |

71 |

Yes |

20 |

|

E13 |

Male |

78 |

Yes |

14 |

|

E14 |

Female |

76 |

Yes |

16 |

|

E15 |

Female |

66 |

No |

18 |

|

E16 |

Male |

66 |

No |

12 |

|

E17 |

Male |

78 |

Yes |

17 |

|

E18 |

Male |

73 |

Yes |

9 |

|

E19 |

Female |

62 |

No |

14 |

|

E20 |

Male |

56 |

No |

18 |

|

E21 |

Female |

57 |

No |

8 |

|

E22 |

Male |

56 |

No |

16 |

|

E23 |

Female |

55 |

No |

16 |

|

E24 |

Male |

58 |

No |

16 |

|

E25 |

Male |

67 |

No |

32 |

|

E26 |

Male |

66 |

No |

17 |

|

E27 |

Female |

79 |

Yes |

20 |

|

E28 |

Female |

63 |

Yes |

10 |

|

E29 |

Female |

68 |

Yes |

17 |

|

E30 |

Male |

70 |

Yes |

23 |

|

E31 |

Female |

64 |

Yes |

11 |

|

E32 |

Male |

75 |

Yes |

14 |

|

E33 |

Male |

72 |

Yes |

20 |

|

E34 |

Male |

72 |

Yes |

17 |

|

E35 |

Female |

68 |

No |

21 |

Source: The author’s own creation.

Table 4. Departures of British residents from Spain (2016-2021)

|

Toward UK |

Unknown destinations |

Re-emigrations |

Total |

|||||

|

Year |

Total |

55 years and older |

Total |

55 years and older |

Total |

55 years and older |

Total |

55 years and older |

|

2016 |

2,007 |

1,161 |

27,638 |

15,350 |

169 |

61 |

29,814 |

16,572 |

|

2017 |

2,926 |

1,505 |

26,113 |

13,920 |

167 |

55 |

29,206 |

15,480 |

|

2018 |

1,962 |

1,140 |

13,794 |

7,099 |

163 |

63 |

15,919 |

8,302 |

|

2019 |

1,682 |

886 |

12,743 |

6,405 |

164 |

50 |

14,589 |

7,341 |

|

2020 |

1,742 |

967 |

11,417 |

6,516 |

152 |

45 |

13,311 |

7,528 |

|

2021 |

2,142 |

1,240 |

21,041 |

12,002 |

176 |

66 |

23,359 |

13,308 |

|

Total 2016-2021 |

12,461 |

6,899 |

112,746 |

61,292 |

991 |

340 |

126,198 |

68,531 |

Source: INE, EVR.

Table 5. Percentage of potential British female returnees (returnees plus residential changes with unknown destinations)

|

% 55 years and older |

% 85 years and older |

% of total, to the UK |

% of total, unknown destination |

|

|

2016 |

49.50 |

48.34 |

48.15 |

49.58 |

|

2017 |

49.26 |

45.19 |

49.83 |

49.93 |

|

2018 |

48.92 |

45.65 |

50.09 |

49.39 |

|

2019 |

49.75 |

44.99 |

48.98 |

48.63 |

|

2020 |

48.37 |

45.88 |

49.02 |

50.69 |

|

2021 |

46.83 |

47.09 |

49.76 |

49.58 |

Source: INE, EVR.

Table 6. Intent and expectation to return

|

Direct intent to return |

Men |

Women |

|

I am thinking of returning over the next few months/years |

4.87 % |

4.50 % |

|

I am thinking of returning but I don’t know when |

6.49 % |

6.91 % |

|

I am thinking of emigrating to another country |

2.27 % |

0.30 % |

|

I am not thinking about returning |

86.4 % |

88.29 % |

|

Future expectation to return |

||

|

It is something expected |

4.55 % |

6.91 % |

|

It is something that could happen |

38.96 % |

45.95 % |

|

It is something that will never happen |

56.49 % |

47.15 % |

Source: The author’s own creation.

Table 7. Chi square between intent and return expectation (binomial) and main independent variables

|

Intent to return |

Expect to return |

|||||

|

χ2 |

df |

p |

χ2 |

df |

p |

|

|

Sex |

0.000 |

1 |

0.985 |

5.597 |

1 |

0.018* |

|

Age (>75) |

0.000 |

1 |

0.997 |

0.313 |

1 |

0.576 |

|

Civil status |

11.622 |

4 |

0.020*º |

1.062 |

4 |

0.900 |

|

Education level |

8.574 |

5 |

0.127º |

10.736 |

5 |

0.057 |

|

Urban/scattered area |

0.902 |

2 |

0.637 |

2.678 |

2 |

0.262 |

|

Census registration |

15.264 |

1 |

0.000*º |

15.425 |

1 |

0.000*º |

|

Year of arrival |

5.437 |

6 |

0.489 |

15.174 |

6 |

0.019* |

|

Property in Spain |

4.356 |

2 |

0.113 |

8.223 |

2 |

0.016*º |

|

Property in UK |

17.185 |

1 |

0.000*º |

43.856 |

1 |

0.000*º |

|

Knowledge of Spanish |

1.564 |

3 |

0.667 |

24.014 |

3 |

0.000*º |

|

Monthly income |

2.835 |

4 |

0.586 |

5.107 |

4 |

0.276 |

|

In favor of Brexit |

2.174 |

3 |

0.537 |

3.754 |

3 |

0.289 |

* Significant relationship.

º Significant relationship controlled by sex (women).

Source: The author’s own creation.

Table 8. Likelihood ratio test for intent and expectation to return

|

Intent to return |

Expect to return |

|||||||

|

-2 Log likelihood of the reduced model |

Chi square |

df |

Sig. |

-2 Log likelihood of the reduced model |

Chi square |

df |

Sig. |

|

|

Interception |

54.209 |

0.000 |

0 |

60.012 |

0.000 |

0 |

||

|

Being married |

65.915 |

11.705 |

1 |

0.001 |

60.359 |

0.347 |

1 |

0.556 |

|

Not being registered |

61.207 |

6.997 |

1 |

0.008 |

69.940 |

9.928 |

1 |

0.002 |

|

Mortgage in Spain |

58.645 |

4.436 |

1 |

0.035 |

60.275 |

0.263 |

1 |

0.608 |

|

Property in UK |

67.958 |

13.748 |

1 |

0.000 |

99.002 |

38.990 |

1 |

0.000 |

|

Happy with Brexit results |

55.555 |

1.346 |

1 |

0.246 |

62.328 |

2.315 |

1 |

0.128 |

Source: The author’s own creation.

RECEPTION: April 2, 2024

REVIEW: July 11, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: December 2, 2024