Figure 1. Theoretical expectation of the effects of transparency policies

Source: Authors’ own creation.

doi:10.5477/cis/reis.191.63-80

What Do Citizens Understand by Transparency? The Punitive Component of Transparency

¿Qué entienden los ciudadanos por transparencia?

El componente punitivo de la transparencia

Lluís Medir Tejado, Jaume Magre Ferran and Esther Pano Puey

|

Key words Trust

|

Abstract This work sheds light on the determinants of citizens’ conception of transparency. Based on theoretical analysis and empirical evidence from focus groups and citizen surveys, the results confirm that citizens with lower levels of institutional trust view transparency as a policy for controlling governments. The causal hypothesis of transparency policies assumes that their fundamental goal is to increase citizen trust in the functioning of political institutions. However, if willingness to control and low prior trust are found to be determinants of citizens’ understanding of transparency, the explanations for the origins of transparency policies may vary, opening up new, less optimistic avenues for interpreting the actual effects of transparency on citizens. |

|

Palabras clave Confianza

|

Resumen Este trabajo arroja luz sobre los determinantes de la concepción ciudadana de la transparencia. A partir del análisis teórico y de la evidencia empírica basada en grupos de discusión y encuestas, los resultados confirman que los ciudadanos con menor nivel de confianza institucional perciben la transparencia como una política de control de los Gobiernos. La hipótesis causal de las políticas de transparencia asume que su objetivo fundamental es incrementar la confianza ciudadana en el funcionamiento de las instituciones políticas. Sin embargo, si la voluntad de control y la baja confianza previa aparecen como determinantes para su comprensión, las explicaciones sobre el origen de las políticas de transparencia pueden variar, abriendo nuevas vías menos optimistas para interpretar los efectos reales de la transparencia sobre los ciudadanos. |

Citation

Medir Tejado, Lluís; Magre Ferran, Jaume; Pano Puey, Esther (2025). «What Do Citizens Understand by Transparency? The Punitive Component of Transparency». Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 191: 63-80. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.191.63-80)

Lluís Medir Tejado: Universidad de Barcelona | lluismedir@ub.edu

Jaume Magre Ferran: Universidad de Barcelona | jmagre@ub.edu

Esther Pano Puey: Fundación Carles Pi i Sunyer | epano@ub.edu

Since the 1980s, transparency has become one of the most recognised remedies for the main dysfunctions in political and administrative systems (Hood and Heald, 2006). The implementation of a transparency policy is seen as a key institutional design principle that helps governments and public administrations achieve a broad range of objectives, including building citizens’ trust in the operation of their institutions, reducing political corruption and enhancing institutional performance (Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2017; Hood, 2010; Hood and Heald, 2006; Meijer, 2013). However, while it is true that the principal target group of transparency is made up of institutions, the primary objective is to improve citizens’ perceptions of those institutions. Transparency is thus intended to change the behaviours of both institutions and citizens: the objectives referring to government and administration are related to making them more competitive, open and functional; whereas the objectives referring to citizens are linked to increasing trust in institutions through greater accountability, participation and citizen control (Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2017).

The rationale that connects citizens and institutions within transparency policies is closely linked to the influential ability of third parties who watch an individual’s or an institution’s operations, thus gauging their performance. This goes beyond the vast opportunities provided by technology for the dissemination and processing of information. In historical terms, the conviction that citizens behave appropriately when they know they are being watched and monitored can be traced back to Bentham’s “panopticon”. Villoria, in a similar vein, pointed out that the idea of control and oversight is at the core of transparency and publicity in government activity: “Checks are insufficient: in comparison with publicity, all other checks are of small account” (Villoria, 2015: 65).

The evolution of transparency policies has been strongly marked by the progressive emergence of political liberalism, which advocated greater control of governments’ operations (Erkkilä, 2012; Hood, 2006). Since then, transparency has become a cornerstone of Western-style liberal democracy and this type of legislation is being adopted in a wide variety of countries around the world (Roberts, 2006; Dragos, Kovač and Marseille, 2019). Apart from the proactive publication of information, the latest developments in transparency appear alongside the right of access (both individual and collective), which takes the form of citizens’ demand for public information. This evolution in the legal framework suggests a gradual strengthening of institutional transparency devices, potentially driven by evidence that the anticipated shift in citizens’ perceptions has not materialised. This paper aims to investigate citizens’ basic understanding of what transparency is at this time of great institutional impact.

This article seeks to explore the concept of transparency as first identified by citizens in a series of focus groups and then followed by a survey in which citizens were asked about their understanding of transparency. The focus groups helped us to identify potential hypotheses and avenues of research, incorporating innovative perspectives on how individuals analyse transparency and situate it personally in relation to the functioning of the institutional system. A questionnaire was designed and distributed to a representative sample of citizens in Catalonia in order to contrast their degree of agreement with different conceptions of transparency linked to institutional trust.

We subsequently focused on local governments to facilitate better allocation of political responsibility, given their proximity and the public’s generally favourable assessment of them. Using municipal governments as the political reference point enabled a clearer identification of responsibilities and, consequently, streamlined the proposed methodological approach.

The aim of this paper is to explore the idea of control as a punitive component in the use of, and demand for, institutional transparency in the face of a lack of trust. The research question guiding this paper can therefore be formulated as: does a lack of trust by citizens lead to a punitive conception of transparency?

This article is structured as follows: The theoretical framework is explained following the introduction. This includes a definition of the concept of transparency to be used; discusses the key theoretical expectations regarding the effects of transparency on citizens; and reviews the major contributions to the relationship between trust and transparency. The main expectations, the data and the methodology employed are then presented. This is followed by the main results of the empirical study and a general discussion, including the ensuing theoretical and practical implications of the research.

The concept and causal construction of transparency policies

According to the main definitions of the concept of transparency, it can be characterised as an institutionalised relationship between public bodies and citizens, based on the provision and exchange of information and data. Bauhr and Nasiritousi (2012) understood it as the disclosure of information that is relevant for evaluating institutions; Cotterrell (2000) conceptualised it as not only the availability of information, but as the ability to engage in participation and use it to create knowledge; Grimmelikhuijsen and Welch (2012), similarly to Meijer (2013), relied on the two dimensions of the concept mentioned above and described transparency as the availability of information about an organisation that allows an external actor to monitor and evaluate its performance.

Based on the above definitions and on the existing legal frameworks, some core aspects can be identified to characterise the foundations of transparency as a public policy. Firstly, and most notably, it is compulsory for most public bodies (institutions and organisations), but with varying levels of coercion. Secondly, it is founded on the requirement that public information held by public bodies be made available (either actively or reactively). Thirdly, this publicity requirement must allow for the basic functioning of the public body in question to be controlled, monitored and understood (mainly by citizens). In other words, the duty of public bodies to provide information on how they operate is primarily based on the principle that citizens (or any stakeholder) can “appraise” and “understand” their operations. The causal construction of policy is thus based on forcing institutional change (openness) to increase citizens’ ability to appraise the performance and workings of public administrations on the basis of the information that they make available. The mere existence of this appraisal exerts pressure on institutions to work better. Finally, the causal construction of policy indicates that the result of the improved performance shaped by transparency may generate citizens’ perception of political institutions as being more trustworthy and legitimate, thus increasing trust.

In general, the emergence of transparency regulations and policies seems to be associated with periods when perceptions of government mismanagement have led to demands for change. In the United States, three particularly important periods can be identified (Roberts, 2006, 2015): the first one covers the two decades preceding World War I, when the popular outcry against political corruption led to a call for greater openness in legislative processes, campaign financing and election administration; the second period was the mid-twentieth century, when the rapid expansion of government bureaucracy resulted in a demand for openness in administrative processes; and the third was the mid-1970s, when the debate over the Vietnam War in the United States of America, the misconduct of federal intelligence agencies and President Nixon’s abuses of power gave rise to another set of reforms to create a more transparent government. Undoubtedly, transparency was clearly seen from the outset as an antidote to corruption (Castellanos, 2022). The idea of control in transparency epitomises both the fight against corruption and against any abuse of power and inefficiency.

At this point, it is relevant to note a certain parallel with the Spanish case, since the enactment of the Spanish legislation on transparency—one of the most recent in the EU—was closely linked to the context of the economic and political crisis that had begun in 2008. With a view to promoting institutional improvement, Law 19/2013 combined three fully complementary aspects: transparency, access to information and good governance. These were accompanied by a significant number of obligations and requirements applicable to the public sector as a whole (Magre et. al., 2021; Medir et. al., 2021). According to Villoria and Izquierdo (2015), the ultimate goal of these legal provisions is to achieve good governance, which is understood as a form of governance that upholds the core values of transparency (accountability, effectiveness, coherence and participation, among others) in both formal and informal institutions. A recent report that emanated from the discussions of the working subgroup for the reform of the Spanish transparency law clearly identified the need to incorporate a stronger open government paradigm across all transparency regulations, especially basic State legislation. Moreover, the multi-tiered nature of the Spanish State has generated a proliferation of regional regulations that has had a significant impact on the public sector (Ballester, 2015). Dabbagh (2015) used data from the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) to analyse citizens’ perceptions and the initial impact of Spanish transparency regulations, concluding that the results had been limited at that time.

Current political rhetoric also assumes that there is a strong relationship between transparency and accountability, with an ensuing increase in trust (Fox, 2007). However, there are sound academic arguments to substantiate that this relationship is neither so obvious nor so direct (for an extensive review, see Villoria, 2021; Michener, 2019; Pozen, 2020; Wang and Guan, 2022). Generally speaking, the expectations about the contribution that transparency makes to increasing institutional trust on the part of citizens are extremely high, whereas the academic understanding of this relationship remains limited.

Interestingly, the analysis proposed by Wang and Guan (2022) can be used to situate the various positions in the literature regarding the possible effects of transparency on trust. They differentiated between models that predicted positive outcomes on trust, those that anticipated negative effects, and those that concluded that there should be no negative effects. The first group of models included the theories of rational choice and deliberative democracy. Models of procedural justice could also justify this positive relationship, although they could in turn identify reasons for increased frustration. Along the same lines of increased frustration and disappointment were the theories that foresaw transparency as having a negative impact on trust. Authors who were doubtful as to the possible benefits of transparency (Byung-Chul Han, 2013; O’Neill, 2002; Etzioni, 2016; Pozen, 2019) were also included in this group. In particular, O’Neill argued back in 2002 that, despite having more information than ever before, transparency may produce results contrary to those expected. In fact, she stated that the most genuine trust is based on the absence of information or on having “no need” to have it. She also noted that it is not surprising for public distrust to have increased during the years in which openness and transparency became more firmly established. While transparency destroys secrecy, it does not constrain deception and deliberate misinformation which subvert relations of trust:

Transparency and openness may not be the unconditional goods that they are fashionably supposed to be. By the same token, secrecy and lack of transparency may not be the enemies of trust (O’Neill, 2002: 18).

Other authors have related the demand for transparency to more ideological aspects. Thus, Etzioni (2016, 2018) considered that transparency is a concept that can be used as a pretext for deregulation. She also agreed with O’Neill that transparency may not produce the expected results and that it often harbours hidden ideological biases. Byung-Chul Han (2013) highlighted the perversity of transparency in the sense that, in his view, it is the opposite of trust: where transparency arises, it is because there is no trust. Pozen (2020) contended that there is a need for a sociological turn in our understanding of the effects of transparency policies to date. He concluded that transparency is not in itself a coherent normative ideal, nor does it have a direct instrumental relationship to any primary objective of governance.

However, it has been accepted by much of the contemporary literature that trust is often treated as a beneficial by-product of transparency policies, based on the assumption that they are mutually reinforcing concepts (Brown, Vandekerckhove and Dreyfus, 2014). Indeed, many transparency and freedom of information laws are legitimised by, and build their causal expectation on, an expected increase in trust.

Most studies on the relationship between trust and transparency have yielded similar results, which are largely inconclusive and highly dependent on context and individual characteristics. In one of the first papers published on the subject, Parent, Vandebeek and Gemino (2005) examined the extent to which e-government initiatives have succeeded in increasing voters’ trust and external political efficacy. They noted that individuals with an a priori trust in government and with high levels of internal efficiency have their trust in government reinforced through electronic interaction with their governments. They also described the opposite situation: individuals with low self-efficacy will not increase their trust, regardless of the medium of interaction and the level of transparency. A few years later, Piotrowski and Van Ryzin (2007) studied the effects of transparency on local government in the United States. The article acknowledged the contextual challenges and classified individuals on the basis of their satisfaction with the services provided by the local government. They hypothesised that citizens who viewed the government’s workings favourably may have less reason to demand that the government be transparent (effectively paving the way for a model of transparency based on control and punishment). The results generally suggested that those citizens who considered government to be already sufficiently open demanded less transparency, while those who described it as opaque tended to demand more. People who were politically engaged and often interacted with the government also tended to demand greater transparency. In other words, the greater citizens’ trust in their local governments was, the lower their interest in transparency regarding certain specific matters. Villoria noted that transparency was itself an effect of distrust in political and economic power (Villoria, 2019: 17).

In later studies, Grimmelikhuijsen (2010) noted that prior trust played an important role in the perception of trust in (local) politics, and therefore perceived levels of trust in local government were largely determined by pre-existing impressions of government. In a later paper, Grimmelikhuijsen hypothesised (Grimmelikhuijsen, 2012) that emotional shortcuts were determinants of trust, but that their influence could be moderated by the effect of transparency. Again, the results were inconclusive, as prior attitudes and predispositions towards government appeared to be more important than the effect of transparency in itself. In a similar vein, Grimmelikhuijsen, Porumbescu, Hong and Im (2013) analysed the effect of transparency on citizens’ trust, but in two completely different national cultures: the Netherlands and South Korea. The paper tested the effects of a particular type of transparency: transparency in decision-making, transparency of information about specific policies, and transparency in policy outcomes and effects. They concluded that transparency seemed to have more negative than positive effects on trust in government and appeared to produce lower impacts in the short term.

Finally, Mabillard and Pasquier, in a more recent study (2015), investigated the endogenous character of transparency in relation to trust. Their starting point was that, if trust in government was most often seen as a positive effect of transparency, it could also be perceived as a factor that influences citizens’ perception of transparency. Their results for the Swiss case led them to question the commonplace assumption that there is a positive correlation between transparency and the production of trust in government. In their conclusions, they stressed that any study on this topic should give considerable attention to the factor of “initial or prior trust” in institutions, as it may play a highly significant role in the observed relationship.

Overall, the meta-analysis conducted by Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen (2017) concluded that, in terms of results, there appeared to be a greater propensity for transparency to improve the quality of financial management and reduce the levels of public-sector corruption than to improve trust, legitimacy and accountability, which had less conclusive results (Cucciniello, Porumbescu and Grimmelikhuijsen, 2017). Their meta-analysis clearly showed that contextual conditions were important, since transparency could contribute positively to accountability in some circumstances but not in others. This review revealed some of the factors that condition the effect of transparency identified so far, which included national culture and values, the type of political issue and participation, the form of government, and the method used to improve transparency. Similarly, another meta-analysis carried out by Wang and Guan (2022) concluded that transparency seemed to indicate a positive impact on trust, but identified numerous nuances depending on the type of transparency involved (including the mechanism, timing, object, as well as the models and methodological strategies used). Villoria (2021) also stressed the significance of the conditional nature of contextual factors in understanding the individual effects of transparency policies.

The analysis of the relationship between transparency and trust, both in terms of theoretical approaches and possible empirical evidence, yielded vastly different results. In addition to the aforementioned moderating factors, it is essential to consider the various elements that may influence how citizens define and perceive transparency. On a general and aggregate basis, the study that comes closest to the approach taken in this article is that by Mabillard and Pasquier (2016), which focused on the relationship between transparency and trust in ten countries during the period from 2007 to 2014. Their research did not confirm a positive relationship between transparency and trust in government. However, it was the first (and almost the only) empirical study that was based on an expectation such as the one in this article: that transparency results from the absence of trust. Indeed, Mabillard and Pasquier found that transparency and trust did not have a linear relationship, and that a certain degree of uncertainty was necessary for trust to exist.

The theoretical framework described above outlines a somewhat inconclusive set of results, leaving room for further contributions to this field. The main results of studies of citizen-oriented effects of, or demands for, transparency—particularly in relation to the connection between transparency and trust in government—were significantly more diverse and heterogeneous than the results of studies analysing the effects on governments.

The theoretical framework indicates that the relationship between trust in government and institutional transparency is not clear-cut and may be influenced by a number of factors. In fact, several of the aforementioned studies highlighted the importance of prior trust both in the perception and assessment of transparency, and in the value of transparency. Thus, when citizens have low levels of trust, both in diffuse and specific terms, they are more likely to view institutional transparency as a control mechanism rather than as a means to trust in or improve a government. Transparency is largely perceived as an instrument of control and oversight of the government apparatus when individual trust is either non-existent or badly eroded, rather than the other way around.

It is plausible, then, that part of the “latent” social demand for transparency is actually punitive and distrustful of the public sector. It is therefore feasible that the results published to date are contradictory because they have not taken into consideration this “latent” or “undisclosed” aspect of transparency. This article seeks to provide an alternative view that can complement the existing ones, based on a model that includes citizens’ perspectives and takes into account the prior trust reservation in order to understand what citizens mean when they demand transparency. Contextual factors and, in particular, prior individual trust are shown to be a determining factor within this framework, as they shape the way in which individuals conceive transparency, including its effects and assessment.

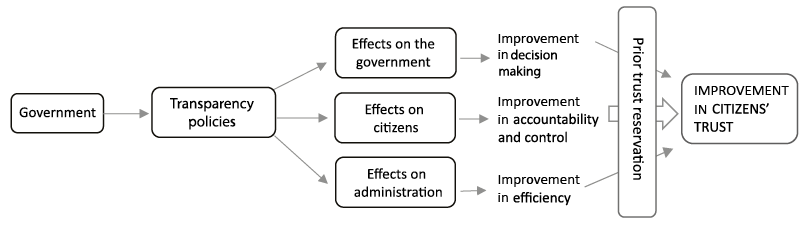

The relationship between transparency policies and trust is based on a causal expectation that the effects of government and public administration transparency would generate an increase in citizens’ trust in the functioning of a government apparatus. This is graphically represented in Figure 1 below.

However, our approach takes into account that prior trust acts as a mediating or conditioning element of transparency policy outcomes. This contribution is based on the assumption that prior trust affects individuals’ perception of transparency, such that a lack of trust changes the way in which individuals conceive and assess the functions and effects of transparency. Prior trust might be a distorting element in the potentially linear, direct and positive relationship between the two concepts. In other words, the causal expectation that increased transparency leads to greater trust would primarily apply to citizens who initially had higher levels of trust, but not to those who lacked such trust from the outset. Thus, the causal mechanisms outlined above are conditioned by whether individuals previously had trust in public institutions.

This alternative explanation means that the prior trust reservation has an effect on citizens’ perception of transparency. The model shown is visually akin to the previous one and operates similarly, but considers the effect of transparency to be mediated by individuals’ prior trust. The mechanism described here may provide a clearer explanation for the commonly observed link between transparency and trust: a transparency policy tends to reinforce or amplify existing levels of trust in individuals who already possess a certain degree of trust; however, it has little impact on individuals with low levels of trust.

The main expectation of this article is that the conception of transparency, understood as the monitoring of public officials by citizens, is generated by the absence of trust. Our working hypothesis, then, connects trust and transparency in such a way that the independent variable—citizens’ prior institutional trust—has an impact on the dependent variable of interest, which is the variation in the conception of institutional transparency. Thus, the main hypothesis is that the lower the level of institutional trust, the higher the probability of considering transparency as an instrument of control rather than as an instrument of institutional improvement, accountability and participation.

Qualitative techniques (focus groups) were used in the initial, more exploratory phase of the study, in order to better delimit the link to be explored and the possible analysis techniques to be employed at a later stage1. In these groups a clear interaction between the variables of trust and transparency was observed, suggesting a certain degree of reciprocal influence.

The results of the focus groups showed that the demand for transparency seemed to be more linked to distrust than to trust, and that trust appeared to be more relevant than other aspects such as efficiency, proximity, prestige and recognised social value. In fact, it was clear from the discussion that institutional transparency was not deemed to be necessary if there was trust. Some participants did not see transparency either as being a necessary component or as having an impact on their level of trust in institutions, while others saw transparency as a requirement in the context of a total lack of trust. In light of these results, it was decided to carry out a survey of a representative sample of citizens in Catalonia to gain a deeper understanding of how they perceive institutional transparency.

The survey was carried out on a sample of 1603 individuals over the age of sixteen2. The dependent variable—the concept of transparency—was operationalised using the following closed question “What does transparency primarily mean to you?”. The response options corresponded to the three main functions of transparency:

We identified the first option as a mechanism for improving accountability and the information available; the second is what we consider to be an oversight device, with no desire to improve the political system other than strictly for control purposes; and the third option is linked to the possibility of enhancing the individuals’ influence on political action. The difficulty in measuring transparency as a negative concept is obvious, particularly considering that a direct question was used. In this case, we analysed the perception of transparency essentially as a mechanism for the control and scrutiny of public officials, as opposed to other perspectives that emphasise a less control-oriented relationship between the governing and the governed. It should be noted that, although the term “control” refers to one of the classic functions of transparency, it still has a connotation that presupposes that citizens have a specific position and relationship to public institutions. If the option of increased participation could be seen as positive, and accountability as proactive monitoring dependent on political will, the term “control” is more negatively loaded, and refers to a vision of strict surveillance and permanent scrutiny that involves distrust almost by default.

The survey also included indicators about trust in institutions. A decision was made to ask participants about the degree of trust in the city council because this is the most highly regarded public institution among citizens and the one that is least rejected, as well as being the most easily identifiable. The main socio-economic variables—age and level of education—were included in the multivariate models, together with the size of the municipality. The degree of trust in the city council was measured on a scale from 0 to 10; municipalities were grouped into four size categories; the respondents’ level of education was classified into three levels; and age was grouped into four intervals.

The methodological strategy sought to assess the relationship between individuals’ levels of trust and the way in which they conceive transparency as an institutional mechanism. A multinomial logistic regression model was selected for the analysis to examine the determining factors that influenced the perception of transparency among the group that viewed it as a control and monitoring policy, compared to those who did not consider control to be the primary characteristic of transparency.

The main indicator of what citizens mean by transparency, therefore, was a closed question designed to test the dimensions that are commonly reported to be part of this concept. The responses were distributed across one third of the study population. Although the options show slight differences, the response that we considered to be the most neutral, reflecting the idea of accountability, was the one that would be placed as the first option.

TablE 1. What does transparency mean to you?

|

Total |

|

|

Proposition 0: What makes it possible to control government. |

30.0 |

|

Proposition 1: What allows citizens to participate. |

29.5 |

|

Proposition 2: What allows government officials to explain what they are doing. |

33.7 |

|

Na-Nk |

3.3 |

Source: Authors’ own creation.

The structure of the question meant that respondents were asked to choose a single answer from the three provided. Running three independent logic models implicitly entailed that the respondent first decided whether they agreed or disagreed with answer 0, repeated the process for answer 1, and then repeated the same process for answer 2. In this way, it might be assumed that the individual would be making three independent decisions when answering the question and could potentially choose more than one alternative. However, the wording of the question did not allow for this answer structure. Each individual was required to choose only one of the alternatives and make a decision in which all three alternatives were considered at the same time. For this reason, the most appropriate model to analyse respondents’ behaviour in this case was a multinomial logistic regression, which allows decisions with more than two alternatives to be modelled.

This model required that one of the responses be defined as a reference point. In this way, the model would provide information on how the probability of choosing the other options with respect to the base alternative changes depending on the value taken by the different explanatory variables. Logically, the reference point was the idea of transparency as an instrument for citizens’ control over those governing them, since the interest of the research lies in establishing the relationship between the degree of institutional trust and the concept of transparency that focuses strictly on oversight.

The active variables in the model are as follows:

The results of the model are shown in Table 2.

TablE 2. Results of the models

|

1 Participation |

2 Accountability |

|

|

Trust of 5-7 |

0.382** (0.151) |

0.559*** (0.144) |

|

Trust of 8-10 |

0.841*** (0.212) |

1.051*** (0.203) |

|

[Ref.: Trust from 0-4] |

||

|

Age: 16-29 |

-0.225 (0.221) |

-0.618*** (0.203) |

|

Age: 30-44 |

-0.562** (0.220) |

-0.774*** (0.200) |

|

Age: 45-59 |

-0.507** (0.216) |

-1.101*** (0.203) |

|

[Ref.: Age: over 59] |

||

|

Municipality size |

-0.198 (0.208) |

-0.337* (0.199) |

|

Municipality size 10,000-100,000 |

-0.294 (0.234) |

-0.170 (0.218) |

|

Municipality size 100,000-500,000 |

-0.119 (0.225) |

-0.246 (0.214) |

|

[Ref.: Mun. +500,000] |

||

|

No formal education |

-0.119 (0.470) |

-0.00413 (0.519) |

|

Compulsory education |

-0.591 (0.474) |

-0.128 (0.521) |

|

Post -compulsory education |

-0.682 (0.473) |

-0.243 (0.520) |

|

Post -compulsory vocational |

-1.246*** (0.468) |

-0.405 (0.513) |

|

[Ref.: Higher education] |

||

|

Constant |

0.931* (0.528) |

0.907 (0.563) |

|

Observations |

1,526 |

1,526 |

Source: Authors’ own creation.

Table 2 shows how the probability of choosing the alternative that regards transparency as a participatory tool for citizens (first column of the model) or the alternative that characterises transparency as a means for better accountability and information (second column of the model) varied with respect to the response of primary interest (base alternative), which is citizens’ oversight ability.

As can be seen in Table 2, the variables of age and institutional trust showed a significant effect on how participants understood transparency. Looking at the first column of the model, an individual declaring a confidence level of between 5-7 (compared to another with a reported confidence level of between 0-4) was associated with an increase in their probability of choosing alternative 1, i.e. enhanced influence of civic participation (compared to choosing alternative 0). When a comparison was made between an individual with a trust level of between 8-10 and one with a trust level of between 0-4, this was also associated with an increase in the probability of choosing alternative 1 over alternative 0. The structure was similar with the age variable: its increase was associated with a decrease in the probability of choosing this alternative with respect to 0, linked to overseeing public institutions. The results exhibited the same trend when analysing column 2 (which compares the effect of the variables age and trust on the probability of choosing alternative 2 with respect to alternative 0).

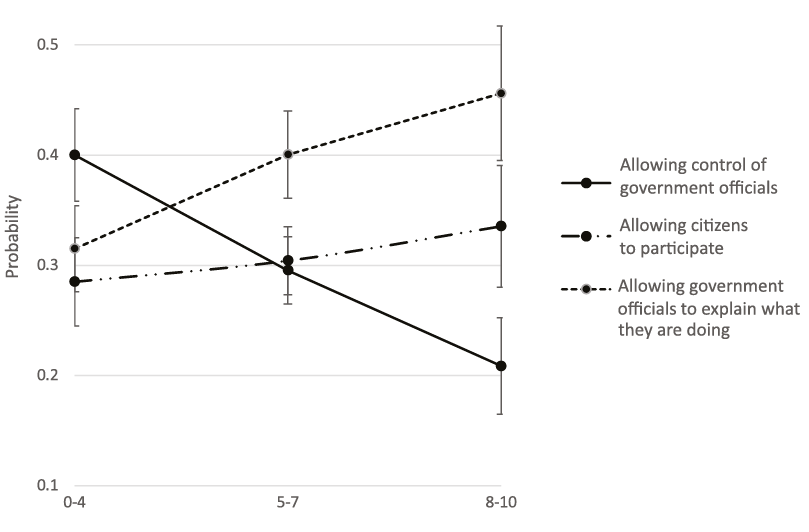

The results indicated that a low level of institutional trust was associated with a higher probability of choosing the response that referred to government oversight. In other words, less institutional trust contributed to seeing transparency as an instrument of control of government officials, thus giving rise to the concept of punitive transparency as a mechanism for penalising lack of trust.

These results revealed the direction of the effect, while the strength of the coefficients obtained from the model indicated its trend; a positive coefficient implies an association with an increased probability, whereas a negative coefficient suggests the opposite. Table 3 completes this information and depicts the marginal effects of the variable measuring the degree of institutional trust. It indicates the number of percentage points by which the probability of choosing each of the response alternatives varied according to citizens’ degree of trust, thus measuring the magnitude. The base category was low institutional trust (ratings of 0-4). The three response alternatives—or the key theoretical dimensions underpinning the concept of transparency—demonstrated distinct relationships with institutional trust. These differences enable the identification of two diverging pathways. Generally speaking, a rise in the degree of institutional trust increased the perception of transparency as a mechanism for accountability, while a decrease in the degree of trust on the part of citizens increased the likelihood of perceiving transparency as a mechanism for controlling public officials.

According to these results, an individual with a trust level of between 7-8 was 10.45 percentage points less likely to choose transparency as a control mechanism than an individual with a trust level of between 0-4. The effect was even more evident when comparing respondents with a higher level of trust (between 8-10), as the probability of choosing the answer linked to the oversight of government officials was almost twenty percentage points lower (19.13 points). Therefore, it is not only the direction of the relationship that indicated a negative association between trust and the perception of transparency as a control mechanism; it is also the magnitude of this relationship that strongly confirmed its validity.

Conversely, trust was linked to a greater likelihood of viewing transparency as a means for enhanced accountability. More specifically, an individual whose trust level was between 5 and 7 was 8.5 % more likely to conceive transparency in this way, compared to someone whose trust level was between 0 and 4. Furthermore, an individual with a trust level of 8 to 10 was 14.1 % more likely to select this answer than someone with a trust level of 0 to 4.

The above description is clearly illustrated in Figure 3, which depicts the percentage change in the probability of selecting a given response according to the respondents’ level of trust.

Finally, it is also interesting to note that the probability of choosing the response linked to greater citizen participation did not seem to be affected by the level of trust (the coefficients were positive, but not significant).

Discussion of results

and conclusions

This paper aims to shed light on the relationship between trust and institutional transparency, an area which, despite being one of the most extensively studied, still has room for further contributions. We have shown that there is not enough clear empirical evidence to have an accurate and robust understanding of the relationships between these two variables. Furthermore, we have noted that, from a theoretical perspective, the conception of transparency’s functions can be traced back to an origin that could be characterised as “punitive”. This goes beyond what has been demonstrated in the literature, as it not only involves a link between transparency and distrust (Villoria, 2019), but also entails that transparency can be instrumentalised as an aggrieved mechanism if there is no prior trust.

Bearing in mind the measurement limitations that we have acknowledged, our results suggest that many of the demands for transparency may be traced back to the perception that something is not operating properly or, more generally, to a need for control based on a lack of trust, as highlighted by some of the theoretical contributions cited above. These findings confirm the results obtained in the focus groups in which citizens who showed greater trust in institutional workings did not believe that there was a need for increased transparency. In contrast, those who had lower trust clearly demanded a more transparent operation.

The quantitative analysis shows a negative relationship between the variables of interest: the perception of transparency related to a will to control public officials increases as trust in institutions decreases. A greater distrust of institutions involves seeing transparency as a means of prioritising oversight over other functions and, in particular, over the most obvious one: accountability. This dynamic suggests an intention to employ transparency as a tool driven by a somewhat punitive rationale.

This finding may help address the difficulties identified in the literature (which were reported in our analysis of the state of the question) in terms of establishing a clear relationship between the two variables (trust and transparency); and it challenges the idea that this relationship is merely linear and direct. While we cannot assert that greater transparency necessarily leads to greater trust, these results indicate that higher levels of distrust tend to drive the use of transparency in a manner that could be seen as having a punitive purpose; the objective does not seem to be greater accountability or avenues for participation, but rather stronger oversight and scrutiny.

The models also show other interesting relationships, particularly those linked to age, since as age increases, the likelihood of viewing transparency as punitive or controlling seems to increase. Similarly, more educated citizens are also more likely to view transparency as an instrument for controlling the government.

Likewise, those participants who do not perceive transparency as an instrument for controlling public officials characterise it as an instrument to increase participation or make it easier for government officials to explain their performance, which increases with trust in a statistically significant way. This reinforces the notion that the objective of control in transparency becomes more pronounced in contexts where distrust exists. Given their lack of trust, citizens attempt to compensate for their misgivings using instruments that allow for increased control; but this does not entail that the mere existence of such mechanisms will ensure the repair or reconstruction of the damaged relationship.

While these results are preliminary, in general terms they open up an interesting avenue for further research in this area. In response to the empirically unfounded optimism that assumes an almost automatic relationship between transparency policies and increased citizen trust in the institutional system, some caution should be applied regarding the potential influence of preexisting levels of trust or distrust on the hypothetical effects of transparency. This oversight-driven logic can readily be associated with a punitive intent that uses transparency as a sanction-based mechanism for strict scrutiny, which is driven by mistrust.

Ballester, Adrián (2015). «Administración Electrónica, Transparencia y Open Data como generadores de confianza en las Administraciones Públicas». Telos: Cuadernos de comunicación e innovación, 100: 120-126.

Brown, Alexander J.; Vandekerckhove, Wim and Dreyfus, Suelette (2014). The Relationship between Transparency, Whistleblowing, and Public Trust. In: P. Ala’i and R. G. Vaughn (eds.). Research Handbook on Transparency (pp. 30-58). Cheltenham/Camberley/Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Byung-Chul, Han (2013). La sociedad de la transparencia. Barcelona: Herder.

Castellanos, Jorge (2022). «Transparencia y participación ciudadana: la lucha contra la corrupción como eje vertebrador del proceso democrático». Revista Española de la Transparencia, 15: 107-129.

Cotterrell, Roger (1999). «Transparency, Mass Media, Ideology and Community». Journal for Cultural Research, 3(4): 414-426.

Cucciniello, Maria; Porumbescu, Gregory A. and Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephan (2017). «25 Years of Transparency Research: Evidence and Future Directions». Public Administration Review, 77(1): 32-44.

Dabbagh Rollán, Víctor Omar (2016). «La Ley de Transparencia y la corrupción. Aspectos generales y percepciones de la ciudadanía española». Aposta. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 68: 83-106.

Dragos, Dacian C.; Kovač, Polonca and Marseille, Albert T. (eds.) (2019). The Laws of Transparency in Action: A European Perspective. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Etzioni, Amitai (2016). Is Transparency the Best Disinfectant?. Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2731880, access 23 September 2023.

Etzioni, Amitai (2018). The Limits of Transparency. In: E. Alloa and T. Dieter (eds.). Transparency, society and subjectivity (pp. 179-201). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Erkkilä, Tero (2012). Government Transparency: Impacts and Unintended Consequences. Heidelberg/New York: Springer.

Fox, Jonathan (2007) «The Uncertain Relationship between Transparency and Accountability». Development in practice, 17(4-5): 663-671.

Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephan G. (2010). «Transparency of Public Decision-making: Towards Trust in Local Government?». Policy & Internet, 2(1): 5-35.

Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephan G. and Welch, Eric W. (2012). «Developing and Testing a Theoretical Framework for Computer-mediated Transparency of Local Governments». Public Administration Review, 72(4): 562-571.

Grimmelikhuijsen, Stephan; Porumbescu, Gregory; Hong, Boram and Im, Tobin (2013). «The Effect of Transparency on Trust in Government: A Cross-national Comparative Experiment». Public Administration Review, 73(4): 575-586.

Hood, Christopher (2010). «Accountability and Transparency: Siamese Twins, Matching Parts, Awkward Couple?». West European Politics, 33(5): 989-1009.

Hood, Christopher and Heald, David (2006). «Transparency: The Key to Better Governance?». Series: Proceedings of the British Academy, 135. Oxford: Oxford University Press for The British Academy.

Mabillard, Vincent and Pasquier, Martial (2015). «Transparency and Trust in Government: A Two-way Relationship». Yearbook of Swiss Administrative Sciences, 6: 23-34. doi: 10.5334/ssas.78

Mabillard, Vincent and Pasquier, Martial (2016). «Transparency and Trust in Government (2007-2014): A Comparative Study». NISPAcee Journal of Public Administration and Policy, 9(2): 69-92.

Magre, Jaume; Medir, Lluís; Pano, Esther; Vallbé, Joan-Josep and Martínez-Alonso, José Luis (2021). La Implementación y los efectos de la normativa de transparencia en los Gobiernos locales de mayor población. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Administraciones Públicas.

Medir, Lluís; Pano, Esther; Vallbé, Joan-Josep and Magre, Jaume (2021). «La implementación de las políticas de transparencia en los municipios españoles de mayor población: ¿path dependency o shock institucional?». Gestión y Análisis de Políticas Públicas, 27: 6-29.

Meijer, Albert (2013). «Understanding the Complex Dynamics of Transparency». Public Administration Review, 73(3): 429-439.

Michener, Gregory (2019). «Gauging the Impact of Transparency Policies». Public Administration Review, 79(1): 136-139.

Nozick, Robert (2014). Anarquía, Estado y utopía. New York: Editorial Innisfree.

O’neill, Onora (2002). A Question of Trust: The BBC Reith Lectures 2002. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Parent, Michael; Vandebeek, Christine. A. and Gemino, Andrew C. (2005). «Building Citizen Trust through E-government». Government Information Quarterly, 22(4): 720-736.

Piotrowski, Suzanne J. and Ryzin, Gregg Van G. (2007). «Citizen Attitudes Toward Transparency in Local Government». The American Review of Public Administration, 37(3): 306-323.

Pozen, David E. (2020). «Seeing Transparency more Clearly». Public Administration Review, 80(2): 326-331.

Roberts, Alasdair (2006). Blacked out: Government Secrecy in the Information Age. Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, Alasdair (2015). Transparency in Government. In: T. Bovaird and E. Loeffler (eds.). Public Management and Governance. London: Routledge.

Villoria, Manuel (2015). «Ética en las administraciones públicas: de los principios al marco institucional». Pertsonak eta Antolakunde Publikoak Kudeatzeko Euskal Aldizkaria, Revista Vasca de Gestión de Personas y Organizaciones Públicas, 9: 8-17.

Villoria, Manuel (2019). «El reto de la transparencia». Anuario de Transparencia Local 2018, 1: 15-41. Madrid: Fundación Democracia y Gobierno Local.

Villoria, Manuel (2021). «¿Qué condiciones favorecen una transparencia pública efectiva?». Revista de Estudios Políticos, 194: 213-247.

Villoria, Manuel and Izquierdo, Agustín (2015). Ética pública y buen gobierno. Madrid: Tecnos.

1 Two two-hour long focus groups with seven and eight members, respectively, were held, as this methodology allows for the exchange of views and ideas and helps to build a better understanding of participants’ motivations and perceptions. The following variables were taken into account:

2 Technical note: uniform sample allocation in four territorial areas (the city of Barcelona, the rest of the Metropolitan Area, the rest of the Metropolitan Region and the rest of Catalonia), stratified by districts in the city of Barcelona and by municipality size in the rest. Random selection of interviewees using interlocking quotas for sex and age. In order to obtain overall results, the data were weighted according to the real weight of each of the territorial areas. The sampling error was ± 2.5 % for the total sample, with a confidence level of 95.5 % and p=q=0.5. For each of the territorial areas, the sampling error was ± 5.0 %. The fieldwork was conducted between January 21 and January 28, 2022.

Figure 1. Theoretical expectation of the effects of transparency policies

Source: Authors’ own creation.

figure 2. Alternative expectation of the effects transparency policies

Source: Authors’ own creation.

TablE 3. Marginal effects of the variable that measures the level of institutional trust

|

dy/dx |

Delta-method std. err. |

Z |

P>|z| |

[95 % conf. Interval] |

||

|

Trust 0-4 |

(base outcome) |

|||||

|

Trust 5-7 _predict Proposition 0 Proposition 1 Proposition 2 |

-0.1045379 0.0191289 0.085409 |

0.0279162 0.026669 0.0277859 |

-3.74 0.72 3.07 |

0.000 0.473 0.002 |

-0.1592526 -0.0331414 0.0309496 |

-0.0498232 0.0713991 0.1398684 |

|

Trust 8-10 _predict Proposition 0 proposition 1 Proposition 2 |

-0.191346 0.0503309 0.1410151 |

0.033918 0.0359109 0.0376705 |

-5.64 1.40 3.74 |

0.000 0.161 0.000 |

-0.257824 -0.0200531 0.0671823 |

-0.1248679 0.1207149 0.2148478 |

Source: Authors’ own creation.

FIGURE 3. Marginal effects of the degree of institutional trust

Source: Authors’ own creation.

RECEPTION: February 23, 2024

REVIEW: September 24, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: December 02, 2024