doi:10.5477/cis/reis.192.105-124

Existential Concerns and Socio-Emotional Distress. Understanding Post-Pandemic Challenges

Preocupaciones existenciales y malestares socioemocionales. Comprendiendo los desafíos de la pospandemia

Erik Dueñas-Rello

Citation

Dueñas-Rello, Erik (2025). “Existential Concerns and Socio-Emotional Distress. Understanding Post-Pandemic Challenges”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 192: 105-124. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.192.105-124)

Erik Dueñas-Rello: Instituto TRANSOC-Universidad Complutense de Madrid | eduenas@ucm.es

Introduction1

The COVID-19 crisis continues to have a profound impact on our societies. The post-pandemic period has been marked by a fourth wave of escalating mental and emotional health issues among the population. These issues have attracted the attention of numerous researchers in Spain (Tezanos, 2022; Ruiz-Frutos and Gómez-Salgado, 2021; Antonovica, Esteban and Antolín, 2023). Nevertheless, it remains essential for sociologists to fully engage with the available survey data on the pandemic’s effects in order to grasp its impact in all its complexity (Torrado et al., 2023). Surveys such as those conducted by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) (Sociological Research Centre) are a highly valuable tool for understanding and addressing the current mental health crisis. This crisis should not be seen as an exceptional outcome of the pandemic, but as a reflection of a raw, vulnerable situation that has entrenched a series of challenges that still affect us today.

Two effects on the socio-affective structure can be identified. On the one hand, there is an increase in socio-emotional distress, referring to the bodily expression of suffering that affects individuals’ emotional states (Bericat, 2018). On the other hand, there are existential concerns, which reflect fears linked to the questioning of one’s identity and life projects (Martuccelli, 2011: 5; Bengtsson and Flisbäck, 2021: 148). The pandemic crisis intensified these existential concerns by radically disrupting everyday life and forcing a rupture in biographical pathways. While the two concepts are related, they occupy a different level of social reality. Socio-emotional distress involves an evaluative relationship with specific events in the surrounding world, whereas existential concerns seemingly entail a deeper level of subjectivity, which has recently been explored by two contemporary representatives of the Frankfurt School of Critical Theory. According to Axel Honneth (2007), human experience is grounded in a mode of existential concern and emotional affliction that orients human interaction towards the surrounding world and forms the basis for structures of recognition and knowledge. Closely aligned with this view is Hartmut Rosa’s notion of resonance (2019, 2023: 3). This is based on a stance of affective openness towards the world, and refers to a form of relationship in which a subject is moved by a force (whether external or internal) that is imbued with deep meaning, which prompts an emotional response through a relationship whereby both are transformed. For Rosa, the loss or disruption of this form of relationship represents a fundamental existential fear, as it impoverishes individuals’ capacity for responsiveness and jeopardises their very construction as subjects. In short, existential concerns represent a negative form of “existential feelings” (Ratcliffe, 2005, 2020), understood as the ontological sense an individual has of their position in the world, which shapes their relationship with the various spheres of reality.

The main objective of this article is to understand the relationship between this ontological level and socio-emotional distress, looking at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on both levels according to age, sex and education level. The article begins with a review of the main theoretical and empirical contributions on existential concerns produced over the last five years. It synthesises three sociological approaches to the existential dimension in order to retrieve some concepts that are central to the understanding of the relationships between this dimension and socio-emotional distress. I will then present the methodological design. I propose a Structural Equation Model (SEM) in order to understand the structure of the relationships between the various concepts involved. This technique identifies latent constructs based on observed variables and examines the regression and covariance relationships between these constructs and other factors. The article concludes with a discussion of the findings and proposes several avenues for future reflection on these issues, while also acknowledging the limitations of the present study.

A state-of-the-art review

In recent years, existential concerns have gained increasing attention in various areas of European sociology. This has been linked to greater interest in the causes and effects of the rise of socio-emotional problems in Western societies, in a period defined by a succession of crisis situations. A review of the specialist literature shows that there are networks of researchers from various parts of Europe (Spain, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Finland) who have addressed these issues in greater depth, but have not engaged in dialogue among them. This section therefore has two aims: on the one hand, to contribute to the sociological understanding of existential issues and their relationship with socio-emotional problems, highlighting the concepts used in the various studies; and on the other hand, to provide a synthesis of the most recent contributions to this field in order to establish a theoretical framework suited to the challenges of the post-pandemic period.

The main Spanish contributions have resulted from a project that aimed to discover new forms of socio-existential vulnerability structurally occurring in Spanish society (Santiago, 2021). They started from a definition of vulnerability as an exposure to risks and hazards that is constitutive of human beings, on the understanding that these hazards have been historically shaped at the intersection between social and existential issues (Martuccelli, 2021). Their findings showed how individuals construe the problems they experience as personal trials; their struggle to overcome these problems gives rise to existential concerns that hinder them from engaging in a resonant relationship with the world (Santiago, 2024: 15). Precarious conditions are typically conducive to heightened tensions, caused by the difficulties in realising independent life projects in contexts of uncertainty, or the erosion and disintegration of social life due to the collapse of employment security structures. This is particularly true for young people (Álvarez-Benavides and Turnbough, 2022; Castrillo and Vicente, 2021); unemployed individuals over the age of forty-five (Briales and Vidal, 2021; Briales, 2022); and caregivers of dependent family members (Artiaga, Martín and Zambrano-Álvarez, 2021; Terrón and Martín, 2021).

These studies highlighted the importance of the subjective experience of precariousness in exploring new forms of vulnerability, alongside its interpretation from the perspective of care ethics. Subjective precariousness is understood to be the inability to envisage and pursue an autonomous life (Tejerina et al., 2013). It can be seen as an existential concern specific to the sphere of work, as it relates to: a sense of self-questioning in the workplace; a feeling of instability in one’s life trajectory; and a loss of self-esteem resulting from the real or perceived collapse of employment security structures (factors that permeate individuals’ understanding of everyday life) (Linhart, 2009; Castel, 1995; Colombo and Rebughini, 2019). Meanwhile, the contributions of the ethics of care can help us to understand how there is an unequal distribution of threats and distress due to the social and political organisation of vulnerability, despite the constitutive fragility of our species (Paperman, 2020; Tronto, 2017).

Patrick Baert, Marcus Morgan and Rin Ushiyama (2022a), from the Universities of Cambridge and Bristol, UK, recently proposed the development of an “existentialist sociology”, which takes as its object “existential milestones”, socially prescribed events that are individually understood as central to achieving a sense of completeness in their lives (p. 24). Grounded in pragmatism, this approach focuses on how individuals engage in solving the problems of their worlds. It proposes analysing decisions, motivations and agency within individual existences as a privileged site for examining the tangle of arrangements and expectations in the macro order where they are embedded (Baert, Morgan and Ushiyama, 2022b: 109; Outhwaite, 2022). The temporal dimension is essential to this approach, considering that these decisions are governed by their orientation towards events charged with significance, producing a potentiality-for-being directed towards the future that gives a direction to biographical projects (Heidegger, 2012 [1927]: §65). This projection, moreover, feeds into the finitude of existence, forcing individuals to make decisions in light of the irreversibility of biographical time (Baert, Morgan and Ushiyama, 2022a: 9).

This approach was presented in a monographic issue of the Journal of Classical Sociology, with critical contributions from other authors. David Inglis (2022) identified several points of convergence with the traditions of existential sociology and existential anthropology developed in the United States. This approach shares the emphasis on human freedom and the ability to construct meaning within social reality with existential sociology, recognising the mutable nature of a being that is continuously shaped through self-actualisation (Kotarba and Melnikov, 2024; Kotarba and Fontana, 1984). However, whereas American approaches often view emotionality as the driving force behind this process (Douglas and Johnson, 1977), the British perspective places greater emphasis on symbolic construction as the key mechanism for articulating existential milestones. The concept of an “existential imperative” (taken from existential anthropology) may resonate with this approach. This concept urges individuals to emerge from the world into which they are thrown, thus seeking a balance between acting in the world and being traversed by the world’s expectations and norms (Jackson and Piette, 2015: 5; Jackson, 2005: 182). Robin Wagner-Pacifici (2022) also underscored that this perspective could be valuable for examining how crisis events affect specific generations, raising the question of whether a generalised sense of existential incompleteness has emerged due to the loss or devaluation of a series of shared experiences. The theoretical framework developed here therefore offers a highly relevant lens for analysing the existential consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (Turner, 2022).

One of the geographical locations that has proven to be most productive in these research areas is the Nordic countries, where the existential concerns faced by young people entering adulthood have been studied in depth in recent years. Östman, Nyman-Kurkiala and Fischer (2020), from the Finnish Åbo Akademi University, investigated the existential meanings associated with being an emerging adult. They highlighted the psychological risks that this transitional stage entails for young people who must learn to manage the freedom, independence and new responsibilities that come with the production of an adult life project (pp. 13-15). In parallel, a group of researchers at the University of Borås in Sweden studied the existential concerns that affect the liminal period of youth. In particular, Lundvall et al. (2019, 2020) identified a shared fear of being lost in an unknown terrain, which also involved being scared of having one’s identity diluted in the face of social demands when producing their adult life projects. For young women, these concerns have been found to arise from managing and finding meaning in their lives when confronted with a set of objectifying and patriarchal demands, which impose an ideal of how to be a young woman (Lundvall et al., 2019). Young men, for their part, described feeling as though they were in a bottomless pit when coping with the difficulties of creating a home or a space in which to rest and find their own subjective meaning. They experienced forms of vulnerability that they concealed for fear of exposing a fragile existence (Lundvall et al., 2020).

These contributions shared a concern for how individuals deal with situations of vulnerability. The findings of the Spanish researchers highlighted the support resources and care networks that people use to mitigate their problems. In the research from Sweden and Finland, the clash between the expectations of autonomy and the effective capacity for self-development of individuals was identified as one of the sources of existential discomfort and tensions. Although the British approach had no empirical applications, it emphasised the way in which biographical projects are constructed and, with it, the perceived capacities to produce them. Perceptions of agency in and control over one’s life are central to individuals’ “subjective well-being” (Bandura, 1993). Autonomy, understood as the effective capacity to develop and pursue one’s own conception of a life worth living (Anderson and Honneth, 2004: 130), concerns both perceived agential capacities and self-assessments, which emerges as a central ontological dimension for understanding the effects of vulnerability. It is important to move towards a more complex conception of these two ideas that summarise subjective well-being, so as not to reproduce the ideal of an independent and self-sufficient individual: both self-assessment and agency are inherently relational concepts, shaped by the interpersonal networks in which individuals are embedded and by existing structures of inequality.

The effects of these existential concerns on the health of young people are one of the main focuses of much of this research. The anxieties caused by these demands can lead to a deterioration in quality of life and subjective well-being. This could result in life crisis experiences, in which affected individuals question their ability to meet the challenge of accessing adulthood (Lundvall et al., 2022; Castrillo Bustamante and Vicente Olmo, 2021). Different existential borderline situations, such as the transition to adulthood (or to retirement), lead to existential questions which are defined by a re-evaluation of lived trajectories and life projects that may result in a questioning of individual identity (Bengtsson and Flisbäck, 2021: 198). This explains the emphasis given to the study of the transition to adulthood, as it is a liminal period defined by exposure to forms of job insecurity and uncertainty (Furlong et al., 2018; Cuervo et al., 2023) that may bring about existential uncertainties, the structural roots of which must be addressed from within the social sciences.

The relationship between existential concerns and socio-emotional distress is a recurring theme in these studies. The difficulties in building independent life projects give rise to problems in individuals’ relationship with the future, leading either to forms of stress in their everyday lives or to a devaluation of their agential capacities, accompanied by symptoms characteristic of depressive states (Hemberg et al., 2024). All the studies mentioned here seem to agree on a distinction between an existential dimension and an emotional plane. While both are affected by exogenous factors, their impact in terms of the existential dimension is at the deep level of the individual’s self-definitions: the re-evaluation it triggers concerns a person’s sense of their position in the world and the way they relate to it. Therefore, existential concerns, subjective precariousness and subjective well-being are understood as concepts belonging to this existential dimension, insofar as they relate to the ways in which individuals engage with and are oriented towards the world (Honneth, 2007; Rosa, 2019; Ratcliffe, 2005). Socio-emotional effects, on the other hand, refer to their relationship with events in the world (Bericat, 2016) mediated by specific social factors, but also by existential feelings that influence how these events are perceived and acted upon (Stephan, 2012).

Based on this distinction and on the elements shared by the aforementioned approaches, in the methodological section I will propose differentiating between several concepts which will be empirically tested. The qualitative findings that were summarised above will be validated through a quantitative approach to these issues. The aim of this article is to contribute to a stronger distinction between existential and socio-emotional problems typically found in the emerging forms of vulnerability, and to examine whether these problems affect specific social positions in different ways.

Objectives of the study

Drawing on the distinction between issues pertaining to the ontological-existential and the emotional dimensions, the primary aim of the research is to explore the relationships between them. Three objectives are therefore proposed, to be evaluated on the basis of a Structural Equation Model:

Methodology

The objective of the proposed methodology was to explore the structural relationships between existential fears or threats, subjective well-being, and the socio-emotional problems experienced by individuals in Spain. A Structural Equation Model (SEM) was used. This technique analyses the relationships between latent constructs and observed variables, enabling the simultaneous estimation of multiple regression lines. SEM requires the formulation of a structural theory, whereby researchers define theoretically grounded relationships between constructs, in order to then empirically test them for validity using a given set of observations (Hair et al., 2019: 700).

Sample

The study explored whether a set of existential concerns could be identified among the Spanish population and how these relate to socio-emotional distress. Data was used from Study 3298, entitled Efectos y consecuencias del coronavirus (I) (Effects and Consequences of Coronavirus, I), conducted by the CIS in October 2020. The survey included questions on existential concerns, individual self-definitions and socio-emotional distress. It was based on 2,861 interviews with members of the Spanish population aged 18 and over. Although the findings are situated within the exceptional context of the pandemic, the emotional and mental health issues it triggered still persist (Pedreira Massa, 2023), thereby ensuring the continued relevance of the results.

Procedure

The model was based on observable variables drawn from question 3 (fears or concerns derived from the pandemic situation), question 14 (self-perceptions of the interviewees) and question 16 (emotional states) of the aforementioned study. Items were recoded to remove missing values. In question 14, the response category “Neither agree nor disagree” was treated as a missing value, as it was not provided to respondents during the survey (see Table 1). In addition, the response scale of the items in question 16 was inverted, so that the categories reflected the degree of impact of the discomfort they measured in an ascending order. The Confirmatory Factor Analysis technique within the SEM (Bollen, 2014) was used to measure the structure of relationships between the different items, which constituted the following latent constructs:

The inclusion of the last factor required selecting cases involving working-age individuals. This made it possible to explore the interconnections between the increasing fragility of employment security, the perceived threats to existential projects, and the resulting emotional impacts. Thus, after dismissing cases with missing values in any of the variables included in the model, the sample consisted of 1820 cases, of which 49.3 % were women and 50.7 % men. In terms of age, 8.6 % were between 18 and 24, 17.4 % between 25 and 34, 25.3 % between 35 and 44, 26.7 % between 45 and 54, and 22.0 % between 55 and 64 years old. Among the sample, 18.6 % had compulsory education or lower educational attainment (ISCED levels 1-2), 39.5 % had completed the Baccalaureate or a Vocational Training course (ISCED levels 3-5), while 41.9 % had a university education (ISCED levels 6-8).

A structural model was proposed that included socio-emotional distress as the only endogenous construct, which could be explained by the exogenous constructs of subjective well-being, existential concerns and subjective precariousness. Covariance relationships were established between the last three constructs, based on the understanding that autonomy, existential uncertainties and material insecurity operate on the same level of social reality—namely, the dimension concerning individuals’ relationship with, and orientation towards, the world (Honneth, 2007). The three constructs measured different forms of existential feeling, such as the anticipatory structure through which one relates to the world as a space of concrete possibilities (Ratcliffe, 2020: 257): subjective well-being referred to the definition of a person’s situation in their environment, while existential concerns and subjective precariousness captured whether this relationship was perceived in terms of threat and insecurity.

The need to sociologise the existential and emotional dimensions led to the introduction of the socio-demographic factors of age, sex and level of education. Age would capture whether these problems affected any particular biographical period to a greater extent, assessing whether youth was more vulnerable to the problems studied here, as a consequence of presentification and the loss of everyday ontological references (Colombo and Rebughini, 2019). The sex variable would assess whether the greater pressures, demands and obligations imposed on women by the political organisation of vulnerability made them more vulnerable to emotional and existential risks. The survey used did not have an income indicator, so the educational attainment variable was introduced as a proxy for respondents’ socio-economic status, while cultural capital operates as a predictor of their economic situation and status position, which could affect the constructs studied here. It was expected that there would be a negative relationship between subjective well-being and socio-emotional distress, as well as a positive relationship between existential concerns and subjective precariousness with socio-emotional distress.

With the exception of age, none of the variables used in the model were interval variables; therefore, Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimation was employed. This method computes polychoric correlation matrices for polytomous items and tetrachoric matrices for dichotomous items, based on the assumption that the items have an underlying continuous and normally distributed response that shapes the categorical responses observed in the sample (Li, 2021). The analysis of the skewness and kurtosis of the variables indicated an absence of multivariate normality, so it was necessary to use the robust version of this estimation, the Weighted Least Squares Mean and Variance (WLSMV), which adjusts the chi-square to the mean and variance of the statistic. All these analyses were carried out using the Lavaan package of the R environment (Rosseel, 2012).

Analysis

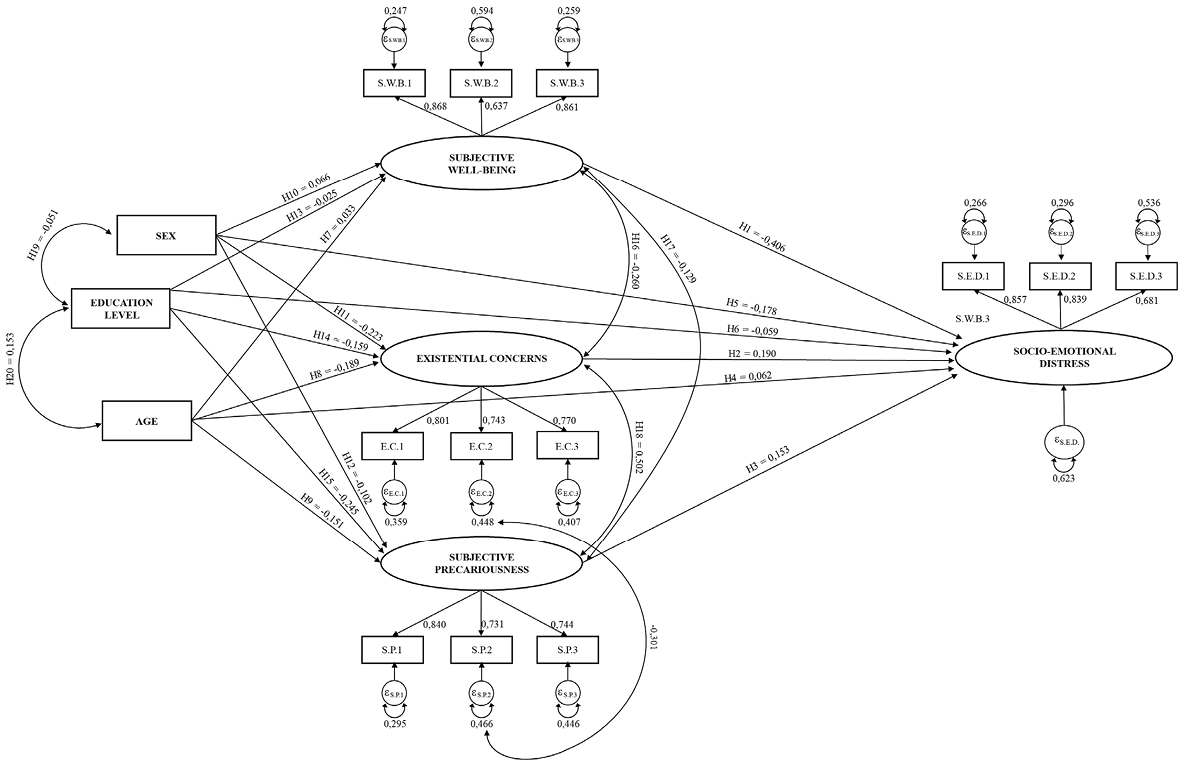

Figure 1 depicts the proposed structural model. This includes the items, the latent constructs and their factor loadings, the covariance and regression relationships, as well as the error terms—both for the items that make up each construct and for the endogenous construct. The standardised estimates of the factor weights and of the covariance and regression relationships, in addition to the variances of the model error terms (represented by bidirectional arrows above each error term) were added. Having checked the modification indices in order to improve the fit, a covariation between the errors of items SED3 and SP2 was included. The model was consistent with the assumption of one-dimensionality for each variable; it grouped the items according to their nature in order to achieve a congeneric model, with three items for each construct. Table 2 details the constructs of the model: all factor loadings were statistically significant and within a range of 0.637-0.868. Annex 1 contains the correlation matrix of the model, which shows that all the correlations between the pairs of items that make up each factor exceeded the value of 0.5; however, higher correlations were found in socio-emotional distress than in existential concerns or subjective precariousness, which is consistent with the nature of each construct. The factors show convergent validity, which presented with an Average Extracted Variance above 0.5. With regard to internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha (ordinal scale items) was calculated from the model’s correlation matrix (Oliden and Zumbo, 2007) and was over 0.8 across all four factors, indicating construct reliability.

The model showed acceptable values for the goodness-of-fit indicators. The χ2 test measured the difference between the observed covariance and that of the estimated model. Due to their sensitivity to sample size, it is recommended to check other incremental fit indices such as TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index) and CFI (Comparative Fit Index), which in the model exceeded the cut-off point of 0.950 (0.991 and 0.987 respectively). The Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) measured the standard deviations of the individual covariances, with its cut-off value at 0.08, above the model value (0.031). Finally, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) indicated how well the model fits the population, correcting for model complexity and sample size, with a cut-off value of 0.5, which indicates that the variables used (and their relationships) were appropriate for the sample used: the model is therefore acceptable (0.028) also under the 90 % confidence index (0.023-0.033).

Table 3 shows the estimates of each relationship between constructs, testing each of the theoretical hypotheses (which are represented in the model by their corresponding acronyms). Most relationships were statistically significant at the α = 0.05 level, with the exception of the covariation relationship between age, sex and education level with subjective well-being. With regard to socio-emotional distress, there was a statistically significant relationship with the three proposed exogenous constructs: there was an inverse relationship with subjective well-being (H1: -0.406), and a positive relationship with existential concerns (H2: 0.190) and subjective precariousness (H3: 0.153). With regard to socio-demographic factors, there was a positive association with age (H4: 0.062), while there was a negative association with sex (H5: -0.178) and education level (H6: -0.059). In total, the explained variance of the factor (R2) was 0.377; this is an acceptable value that shows the explanatory power of the model to understand the relationships between socio-emotional distress and its predictor variables, since they were all statistically significant.

The relationships between the exogenous constructs and the socio-demographic factors were statistically significant, except for their relationships with the subjective well-being construct. Age had an inverse relationship with existential concerns (H8: -0.189), with these fears decreasing as age increased; the same tendency as in their relationship with subjective precariousness (H9: -0.151). With regard to sex, women had more existential concerns than men (H11: -0.223) and higher levels of subjective precariousness (H12: -0.102). Education level also affected both forms of existential fears, both of which decreased as educational level increased (H14: -0.159; H15: -0.245). All the exogenous constructs were statistically associated. The highest association was found to be between existential concerns and subjective precariousness (H18: 0.502), while changes between subjective well-being and existential concerns were negative (H16: -0.260), as was the case between subjective well-being and subjective precariousness (H17: -0.129). Finally, whereas there was no statistically significant relationship between sex and education level (H19, above p-value 0.05), there was an association between age and education level that should be taken into consideration (H20: 0.133).

Discussion

The SEM shows the relationship between the ontological level (or orientation towards the world) and the impact of socio-emotional distress on the Spanish population during the pandemic crisis. The three proposed exogenous constructs measured different aspects of the disposition towards the world that affect the endogenous construct to different extents and may entail a qualitatively different relationship. Subjective well-being, constituted by self-assessment, concerns the agential capacities that people have in their relationship with the world; individuals’ self-perceptions affect the degree of suffering they experience in threatening situations (Bandura, 1993: 133). This accounts for the direct relationship between the two constructs, indicating that higher levels of self-assessment (H1) among respondents are associated with a lower degree of socio-emotional distress. This was also the factor with the greatest explanatory power in the endogenous construct. The lack of effects of socio-demographic factors on this construct (H7, H10 and H13) indicates that a person’s self-efficacy assessment is a self-explanatory factor of a person’s self-efficacy perspectives in their relationship with the world; however, its relationship with the other socio-existential constructs indicates that this disposition is affected by changes in the social environment.

Existential concerns and subjective precariousness constitute a type of non-elemental existential feeling that becomes pathological by negatively affecting the structure of one’s relationship with the world as a whole (Ratcliffe, 2005: 59; Stephan, 2012: 160). According to Hartmut Rosa (2019: 237), the devaluation of the affective-existential structure that we use to orient ourselves towards the world—caused by fears related to a loss of purpose or direction in life trajectories—can lead to an increase in depressive or anxiety-related disorders. In this sense, the greater explanatory power of existential concerns on the socio-emotional distress factor, compared to subjective precariousness, can be understood as the former reflecting a deeper erosion of individuals’ existential structure—one that concerns the relationships they establish with themselves and with the world as a whole (H2), and not with a particular sphere. This does not diminish the central role of the employment sphere and economic insecurity in the impact of socio-emotional distress (H3), insofar as precariousness involves processes of re-articulation and questioning of life trajectories and biographical projects (Carreri, 2022).

The negative relationship between age and these existential feelings (H8 and H9) can be explained by the double social and existential challenge faced by young people in the building and production of independent life projects for their transition to adulthood. This is a task fraught with uncertainties and ontological insecurities (Östman, Nyman-Kurkiala and Fischer, 2020: 13) which, in Spain, is necessarily undertaken amid instability and precariousness. These conditions make the fear of lacking a sense of direction for one’s biographical trajectory all the more pronounced. Women appear to experience these feelings to a greater extent, with existential concerns having a stronger impact (H11) than subjective precariousness (H12). This aligns with recent research that identified the sources of pressure and demands across different spheres—pressures that affect women more directly (Lundvall et al., 2019). Likewise, people with lower levels of education have a higher degree of subjective precariousness (H15) than existential concerns (H14). As cultural capital is closely related to the position in the employment structure, this tendency is explained by the fact that they have fewer resources with which to face economic uncertainty, which can cause them to feel less prepared for the sphere to which this construct refers. The fact that young people, women and individuals with lower levels of education exhibited greater fear of precariousness can be accounted for by the fact that these groups are affected by precarious life trajectories to a large extent (Verd and López-Andreu, 2012: 146).

The fears associated with these two pathological forms of existential feelings can be understood as stemming from self-actualisation or personal change (Douglas and Johnson, 1977; Piette and Jackson, 2015), which turns into an obligation under temporal pressures that impose norms and expectations in order to fulfil socio-biographical demands (Baert, Morgan and Ushiyama, 2022a: 12). This temporal pressure will be navigated differently depending on the resources available (e.g., education); but also according to individuals’ self-definitions, shaped by differences in agential capacity to confront challenges and define a set of meaningful existential milestones that lend purpose to their biographical projects (Baert, Morgan and Ushiyama, 2022b: 110). This explains the negative relationship of subjective well-being with existential concerns (H16) and subjective precariousness (H17). Taken together, the lack of resources to address these fears, as well as the inability to produce meaning that buffers existential fears, is a source of profound socio-emotional distress.

Regarding the relationships between sociodemographic factors and socio-emotional distress, their greater prevalence among women stands out (H5), making it a primary explanatory factor in Spain, as highlighted by recent studies (Pedrera Massa, 2023: 41; González-Sanguino et al., 2021). The fact that these problems had a greater impact on women during the pandemic may reflect the increased demand for forms of care in the absence of institutional support, both in terms of caring for physically dependent people and in terms of a generalised need for emotional support (tasks which may fall to them, as they are more associated with caregiving) (Cheshire-Allen and Calder, 2022: 61). There was a weak association between socio-emotional distress and age and educational level, although it was statistically significant. The greater effect of this distress on respondents with compulsory or primary education attainment can be explained by the fewer resources they have available to cope with shocks such as those caused by the crisis (H6). The increase in distress as age increases (H4) may be due to what Bericat (2018: 321) identified as an “emotional mid-life crisis” in Spanish society, as emotional well-being decreases with increasing age, especially affecting cohorts between forty and sixty years old. However, when considering how age influences negative existential feelings, socio-emotional issues among the young population could be strongly linked to existential concerns.

Conclusions

This study introduces a conceptual distinction between emotional suffering and existential fears, grounded in a model that incorporates an understanding of the ontological dimension—conceived as a fundamental orientation towards the world—which precedes and potentially accounts for such forms of suffering. The relationships between different existential feelings (existential concerns and subjective precariousness) and the perceived autonomy of individuals regarding the suffering related to emotional issues in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis have been addressed. The effects of age, sex and education level on the two dimensions have been studied in order to identify factors that can explain the impact of some problems that became chronic upon experiencing such an exceptional health situation. Although the analysis was limited to a specific period, it allows us to understand the importance of the individual’s relationship with the world on an existential-ontological level when it comes to emotional problems. The SEM technique has enabled each of the objectives to be met:

The implications of these findings require further investigation. In quantitative terms, it is necessary to replicate the structure of relationships proposed in the post-pandemic situation. One possibility would be to replicate the questions in this survey, detaching them from the pandemic context, and to include other items that constitute specific existential concerns of great relevance today, such as concerns about the climate crisis, political polarisation or the risk of nuclear war, among others. The findings of this study could also be complemented by a qualitative approach that addresses the constructs analysed in the proposed model from the life-worlds of the groups most affected by the problems studied here.

In sum, the research presented in this paper is an empirically grounded contribution to a sociology of our relationship to the world that poses existential and emotional questions. As a sample with a large number of observations covering the general Spanish population has been used, the conclusions constitute a validated and reliable reference for further study of the relationships between the two dimensions in the coming years.

Bibliography

Alvarez-Benavides, Antonio and Turnbough, Matthew L. (2024). “Supporting Oneself: The Tensions of Navigating a Prolonged Crisis Among Spanish Youth”. Current Sociology, 72(1): 101-119. doi: 10.1177/00113921221093094

Anderson, Jason and Honneth, Axel (2005). Autonomy, Vulnerability, Recognition, and Justice. In: J. Christman and J. Anderson (eds.). Autonomy and the Challenges to Liberalism: New Essays (pp. 127-149). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Antonovica, Arta; de Esteban Curiel, Javier and Antolín Prieto, Rebeca (2023). “Cambios sociopsicológicos determinantes desde la perspectiva de género durante la pandemia de COVID-19”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 184: 3-22. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.184.3

Artiaga Leiras, Alba; Martín Palomo, M.ª Teresa and Zambrano-Álvarez, Inmaculada (2021). Cuidadoras de la red familiar: procesos de vulnerabilización y autogobierno. In: J. Santiago (ed.). Caras y soportes de la vulnerabilidad (pp. 161-184). Madrid: La Catarata.

Baert, Patrick; Morgan, Marcus and Ushiyama, Rin (2022a). “Existence Theory: Outline for a Theory of Social Behaviour”. Journal of Classical Sociology, 22 (1): 7-29. doi: 10.1177/1468795X21998247

Baert, Patrick; Morgan, Marcus and Ushiyama, Rin (2022b). “Existence Theory Revisited: A Reply to Our Critics”. Journal of Classical Sociology, 22(1): 107-116. doi: 10.1177/1468795X211056080

Bandura, Albert (1993). “Perceived Self-Efficacy in Cognitive Development and Functioning”. Educational Psychologist, 28(2): 117-148. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3

Bengtsson, Mattias and Flisbäck, Marita (2021). “Illuminating Existential Meaning: A New Approach in the Study of Retirement”. Qualitative Sociology Review, 17(1): 196-214. doi: 10.18778/1733-8077.17.1.12

Bericat, Eduardo (2016). “The Sociology of Emotions: Four Decades of Progress”. Current Sociology, 64(3): 591-513. doi: 10.1177/0011392115588355

Bericat, Eduardo (2018). Excluidos de la felicidad. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Bollen, Kenneth A. (2014). Structural Equations with Latent Variables. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Briales, Álvaro (2022). “Temporalities of Vulnerability: Unemployment Tactics During the Spanish Crisis”. Time & Society, 31(4): 584-607. doi: 10.1177/0961463X221122485

Briales, Álvaro and Maira Vidal, M.ª Mar (2021). La crisis de los soportes laborales: experiencias de vulnerabilidad en el desempleo de personas mayores de 45 años. In: J. Santiago (ed.). Caras y soportes de la vulnerabilidad (pp. 85-108). Madrid: La Catarata.

Carreri, Anna (2022). “Imagined Futures in Precarious

Working Conditions: A Gender Matter?”. Current Sociology, 70(5): 742-760. doi: 10.1177/00113921211001089

Castel, Robert (1995). Les Métamorphoses de la question sociale. Paris: Fayard.

Castrillo Bustamante, Concepción and Vicente Olmo, Ana (2021). El futuro es un abismo: jóvenes y proyectos biográficos en tiempos de crisis. In: J. Santiago (ed.). Caras y soportes de la vulnerabilidad (pp. 109-134). Madrid: La Catarata.

Cheshire-Allen, Marie and Calder, Gideon (2022). “’No One Was Clapping for Us’ Care, Social Justice and Family Carer Wellbeing During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Wales”. International Journal of Care and Caring, 6(1-2): 49-66. doi: 10.1332/239788221X16316408646247

CIS (2020). Efectos y consecuencias del coronavirus (I). Study 3298. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. Available at: https://www.cis.es/detalle-ficha-estudio?origen=estudio&idEstudio=14530, access February 1, 2024.

Colombo, Enzo and Rebughini, Paola (2019). Youth and the Politics of the Present. Coping with Complexity and Ambivalence. Abingdon: Routledge.

Cuervo, Hernan; Maire, Quentin; Cook, Julia and Wyn, Johanna (2023). “Liminality, COVID-19 and the Long Crisis of Young Adults’ Employment”. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 58(3): 607-623. doi: 10.1002/ajs4.268

Douglas, Jack D. and Johnson, John M. (1977). Existential Sociology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Furlong, Andy; Goodwin, John; O’Connor, Henrietta; Hadfield, Sarah; Hall, Stuart; Lowden, Kevin and Plugor, Réka (2018). Young People in the Labour Market. Past, Present, Future. London: Routledge.

González-Sanguino, Clara; Ausín, Berta; Castellanos, Miguel A.; Saiz, Jesús and Muñoz, Manuel (2021). “Mental Health Consequences of the Covid-19 Outbreak in Spain. A Longitudinal Study of the Alarm Situation and Return to the New Normality”. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 107, 110219. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110219

Hair Jr, Joseph F.; Black, William C.; Babin, Barry J. and Anderson, Rolph E. (2019). Multivariate Data Analysis. Hampshire: Cengage, eighth edition.

Heidegger, Martin (2012) [1927]. Ser y tiempo. Madrid: Trotta.

Hemberg, Jessica; Sundqvist, Amanda; Korzhina, Yulia; Östman, Lillemor; Gylfe, Sofia; Gädda, Frida; Nystrom, Lisbet; Groundstroem, Henrik and Nyman-Kurkiala, Pia (2024). “Being Young in Times of Uncertainty and Isolation: Adolescents’ Experiences of Well-being, Health and Loneliness During the COVID-19 Pandemic”. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 29(1). doi: 10.1080/02673843.2024.2302102

Honneth, Axel (2007). Reification. A study in recognition theory. Madrid: Katz.

Inglis, David (2022). “Existentialising Existence Theory and Expanding the Sociology of Existential Milestones”. Journal of Classical Sociology, 22(1): 30-48. doi: 10.1177/1468795X211049126

Jackson, Michael (2005). Existential Anthropology: Events, Exigencies and Effects. New York: Berghahn Books. doi: 10.3167/9781571814760

Jackson, Michael and Piette, Albert (eds.) (2015). What Is Existential Anthropology? New York: Berghahn Books. doi: 10.2307/j.ctt9qcthj

Kotarba, Joseph and Fontana, Andrea (1984). The Existential Self in Society. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kotarba, Joseph and Melnikov, Andrii (2024). Existential Sociology. In: H. Wardle, N. Rapport and A. Piette (eds). The Routledge International Handbook Of Existential Human Science (pp. 12-22). Abingdon: Routledge.

Li, Cheng-Hsien (2021). “Statistical Estimation of Structural Equation Models with a Mixture of Continuous and Categorical Observed Variables”. Behavior Research Methods, 53: 2191-2213. doi: 10.3758/s13428-021-01547-z

Linhart, Danièle (2009). “Modernisation et précarisation de la vie au travail”. ECIC Papers, 43. doi: 10.1387/pceic.12241

Lundvall, Maria; Lindberg, Elisabeth; Hörberg; Ulrica; Carlsson, Gunilla and Palmér, Lina (2019). “Lost in an Unknown Terrain: A Phenomenological Contribution to the Understanding of Existential Concerns as Experienced by Young Women in Sweden”. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being,14(1): 1658843. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2019.1658843

Lundvall, Maria; Hörberg, Ulrica; Palmér, Lina; Carlsson, Gunilla and Lindberg, Elisabeth (2020). “Young Men’s Experiences of Living with Existential Concerns: “Living Close to a Bottomless Darkness’’. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 15(1), 1810947. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1810947

Lundvall, Maria; Hörberg, Ulrica; Palmér, Lina; Carlsson, Gunilla and Lindberg, Elisabeth (2022). “Finding an Existential Place to Rest: Enabling Well-Being in Young Adults”. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 17(1). doi: 10.1080/17482631.2022.2109812

Martuccelli, Danilo (2011). “Une sociologie de l’existence est-elle possible?”. SociologieS. doi: 10.4000/sociologies.3617

Martuccelli, Danilo (2021). Vulnerability: Una nueva representación de la vida social. In: J. Santiago (ed.). Caras y soportes de la vulnerabilidad (pp. 43-58). Madrid: La Catarata.

Muñoz Terrón, José María and Martín Palomo, M.ª Teresa (2021). Cuidar (desde) la vulnerabilidad: prácticas, agencias y soportes. In: J. Santiago (ed.). Caras y soportes de la vulnerabilidad (pp. 185-208). Madrid: La Catarata.

Oliden, Paula Elosua and Zumbo, Bruno D. (2008). “Coeficientes de fiabilidad para escalas de respuesta categórica ordenada”. Psicothema, 20(4): 896-901.

Östman, Lillemor; Nyman-Kurkiala, Pia and Fischer, Regina Santamäki (2020). “To Understand the Meaning of Being an Emerging Adult From a Caring Science Perspective-A Phenomenologic Hermeneutic Study”. International Journal for Human Caring, 24(1). doi: 10.20467/1091-5710.24.1.12

Outhwaite, William (2022). “Existence as a Predicament”. Journal of Classical Sociology 22(1): 95-99. doi: 10.1177/1468795X211049240

Paperman, Patricia (2011). Les gens vulnérables n’ont rien d’exceptionnel. In P. Paperman and S. Laugier (eds.). Le souci des autres. Paris: Éditions de l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales. doi: 10.4000/books.editionsehess.11719

Pedreira Massa, José Luis (2023). Mental Health in the Pandemic COVID-19: Towards Post-pandemic. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Ratcliffe, Matthew (2005). “The Feeling of Being”. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 12(8-10): 43-60.

Ratcliffe, Matthew (2020). Existential Feelings. In: T. Szanto and H. Landweer (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Phenomenology of Emotion (pp. 250-261). Abingdon: Routledge.

Rosa, Hartmut (2019). Resonance. A Sociology of the Relationship with the World. Madrid: Katz.

Rosa, Hartmut (2023). “Resonance as a Medio-passive, Emancipatory and Transformative Power: A Reply to My Critics”. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 10(1): 1-16. doi: 10.1186/s40711-023-00195-4

Rosseel, Yves (2012). “lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modelling”. Journal of Statistical Software, 48 (2): 1-36. Available at: http://www.jstatsoft.org/v48/i02/, access February 1, 2024.

Ruiz-Frutos, Carlos and Gómez-Salgado, Juan (2021). “Efectos de la pandemia por COVID-19 en la salud mental de la población trabajadora”. Archivos de Prevención de Riesgos Laborales, 24(1): 6-11. doi: 10.12961/aprl.2021.24.01.01

Santiago, Jose (2021). Caras y soportes de la vulnerabilidad. Madrid: La Catarata.

Santiago, Jose (2024). “Existential Concerns and Supports. An Investigation into Vulnerability”. Papeles del CEIC, 2024(1): 1-7. doi: 10.1387/pceic.25840

Stephan, Achim (2012). “Emotions, Existential Feelings, and their Regulation”. Emotion Review, 4(2): 157-162. doi: 10.1177/1754073911430138

Tejerina, Benjamín; Cavia, Beatriz; Fortino, Sabine and Calderón, Ángel (eds.). Crisis and Precariousness of Life. Valencia: Tirant Lo Blanch.

Tezanos, José Félix (ed.) (2022). Cambios sociales en tiempos de pandemia. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Torrado, José Manuel; Duque-Calvache, Ricardo; Castellano García, Laura and Fernández-Pérez, Ángel (2023). “Fuentes para el estudio de las consecuencias sociales de la COVID-19. Una revisión de las encuestas realizadas en España (2020-2021)”. OBETS. Social Science Journal, 18(1): 209-220. doi: 10.14198/obets.21909

Tronto, Joan (2017). “There is an Alternative: Homines Curans and the Limits of Neoliberalism”. International Journal of Care and Caring, 1(1): 27-43. doi: 10.1332/2393288788217X14866281687583

Turner, Bryan S. (2022). “Vulnerability and Existence Theory in Catastrophic Times”. Journal of Classical Sociology, 22(1): 90-94. doi: 10.1177/1468795X211049303

Verd, Joan Miquel and Lopez-Andreu, Marti (2012). “La inestabilidad del empleo en las trayectorias laborales un análisis cuantitativo”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, (138): 135-48. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.138.135

Wagner-Pacifici, Robin (2022). “At the Intersection of Existence, Events, and Milestones: A Response to ‘Existence Theory’”. Journal of Classical Sociology, 22(1): 85-89. doi: 10.1177/1468795X211048648

1 This article is part of a pre-doctoral research project funded by a grant from the Autonomous Community of Madrid for the recruitment of pre-doctoral research staff in training. I would like to thank Daniel López Roche for his comments on the methodological aspects of the study, which have significantly improved the text.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtoses and recoded scales of the variables used

|

Mean |

S.D. |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

|

Scale 0-Strongly Disagree, 3-Strongly Agree |

||||

|

I generally feel active and vigorous (SWB1) |

2.250 |

0.800 |

-1.001 |

0.678 |

|

Most days I feel I have achieved what I set out to achieve (SWB2) |

1.927 |

0.822 |

-0.559 |

-0.069 |

|

I generally feel good about myself (SWB3) |

2.371 |

0.697 |

-1.069 |

1.334 |

|

Scale 0-Never or hardly ever, 3-Always or nearly always |

||||

|

Felt sad (SED1) |

0.653 |

0.756 |

1.120 |

1.054 |

|

Felt depressed (SED2) |

0.544 |

0.743 |

1.345 |

1.428 |

|

Felt lonely (SED3) |

0.327 |

0.661 |

2.281 |

5.179 |

|

Scale 0-No, 1-Yes |

||||

|

Concern about and fear of the future (EC1) |

0.815 |

0.388 |

-1.624 |

0.639 |

|

Fear of no longer being able to undertake life projects such as emancipation, starting a business or travelling (EC2) |

0.563 |

0.496 |

-0.255 |

-1.936 |

|

Fear of not resuming their life as it was before the pandemic (EC3) |

0.612 |

0.488 |

-0.457 |

-1.792 |

|

Fear of losing one’s job or that a family member might lose theirs (SP1) |

0.674 |

0.469 |

-0.740 |

-1.453 |

|

Concern about losing one’s job or that a family member might lose theirs (SP2) |

0.401 |

0.490 |

0.403 |

-1.838 |

|

Uneasiness about not being able to cover one’s expenses (mortgages, rent, loans, utilities, telephone, etc.) (SP3) |

0.435 |

0.496 |

0.264 |

-1.932 |

Source: Prepared by the author based on CIS Study 3298.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 192, October - December 2025, pp. 105-124

Figure 1. SEM

Source: Prepared by the author based on CIS Study 3298.

Existential Concerns and Socio-Emotional Distress. Understanding Post-Pandemic Challenges

Table 2. Assessment of the latent constructs of the model and goodness-of-fit estimators

|

Estimation (standard error) |

Standardised estimation |

|

|

Subjective Well-being |

||

|

SWB1 |

1.000 (-) |

0.868*** |

|

SWB2 |

0.733 (0.023) |

0.637*** |

|

SWB3 |

0.991 (0.027) |

0.861*** |

|

Cronbach’s alpha = 0.829 |

||

|

Average Extracted Variance = 0.635 |

||

|

Socio-emotional Distress |

||

|

SED1 |

1.000 (-) |

0.857*** |

|

SED2 |

0.978 (0.027) |

0.839*** |

|

SED3 |

0.785 (0.028) |

0.681*** |

|

Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.852 |

||

|

Average Extracted Variance = 0.670 |

||

|

Existential Concerns |

||

|

EC1 |

1.000 (-) |

0.801*** |

|

EC2 |

0.925 (0.047) |

0.743*** |

|

EC3 |

0.960 (0.050) |

0.770*** |

|

Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.831 |

||

|

Average Extracted Variance = 0.624 |

||

|

Subjective Precariousness |

||

|

SP1 |

1.000 (-) |

0.840*** |

|

SP2 |

0.865 (0.046) |

0.731*** |

|

SP3 |

0.881 (0.044) |

0.744*** |

|

Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.828 |

||

|

Average Extracted Variance = 0.624 |

||

|

SED3 error ↔ SP2 error |

-0.137 (0.031) |

-0.301*** |

|

χ2: 174.846, Df: 72, p-value: 0.000 |

||

|

CFI 0.991 |

||

|

TLI: 0.987 |

||

|

SRMR: 0.031 |

||

|

RMSEA: 0.028 (C.I. 90 %: 0.023-0.033) |

||

+p< 0.100; *p< 0.050; **p< 0.010; ***p< 0.001.

Source: CIS Study 3298, author’s calculations using WLSMV estimation.

Table 3: Relations between variables of the model

|

Structural relationship |

Parameter |

Standardised estimation |

|

H1: Subjective Well-being → Socio-emotional Distress |

-0.413 (0.030)*** |

-0.406 |

|

H2: Existential Concerns → Socio-emotional Distress |

0.204 (0.050)*** |

0.190 |

|

H3: Subjective Precariousness → Socio-emotional Distress |

0.157 (0.044)*** |

0.153 |

|

H4: Age → Socio-emotional Distress |

0.004 (0.002)* |

0.062 |

|

H5: Sex → Socio-emotional Distress |

-0.157 (0.028)*** |

-0.178 |

|

H6: Educational level → Socio-emotional Distress |

-0.052 (0.026)* |

-0.059 |

|

H7: Age → Subjective Well-being |

0.002 (0.002) |

0.033 |

|

H8: Age → Existential Concerns |

-0.013 (0.002) *** |

-0.189 |

|

H9: Age → Subjective Precariousness |

-0.011 (0.002)*** |

-0.151 |

|

H10: Sex → Subjective Well-being |

0.057 (0.030)+ |

0.066 |

|

H11: Sex → Existential Concerns |

-0.183 (0.031)*** |

-0.223 |

|

H12: Sex→ Subjective Precariousness |

-0.088 (0.031)** |

-0.102 |

|

H13: Educational level→ Subjective Well-being |

-0.022 (0.027) |

-0.025 |

|

H14: Educational level → Existential Concerns |

-0.131 (0.028)*** |

-0.159 |

|

H15: Educational level → Subjective Precariousness |

-0.211 (0.028)*** |

-0.245 |

|

H16: Subjective Well-being ↔ Existential Concerns |

-0.176 (0.025)*** |

-0.260 |

|

H17: Subjective Well-being ↔ Subjective Precariousness |

-0.093 (0.025)*** |

-0.129 |

|

H18: Existential Concerns ↔ Subjective Precariousness |

0.326 (0.028)*** |

0.502 |

|

H19: Sex and Education level |

-0.051 (0.033) |

-0.051 |

|

H20: Age ↔ Educational level |

1.624 (0.322)*** |

0.133 |

|

R2 of Socio-emotional Distress = 0.377 |

+p< 0.100; *p< 0.050; **p< 0.010; ***p< 0.001.

Source: CIS Study 3298, author’s calculations using the WLSMV estimator.

RECEPTION: May 6, 2024

REVIEW: October 28, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: March 11, 2025

Annex

Table 4. Correlation matrix of the variables of the model

|

SWB1 |

SWB2 |

SWB3 |

SED1 |

SED2 |

SED3 |

EC1 |

EC2 |

EC3 |

SP1 |

SP2 |

SP3 |

Sex |

Age |

Education Level |

|

|

SWB1 |

1 |

||||||||||||||

|

SWB2 |

0.553 |

1 |

|||||||||||||

|

SWB3 |

0.747 |

0.548 |

1 |

||||||||||||

|

SED1 |

-0.359 |

-0.264 |

-0.356 |

1 |

|||||||||||

|

SED2 |

-0.352 |

-0.258 |

-0.349 |

0.719 |

1 |

||||||||||

|

SED3 |

-0.286 |

-0.210 |

-0.283 |

0.583 |

0.571 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

EC1 |

-0.183 |

-0.134 |

-0.181 |

0.283 |

0.277 |

0.225 |

1 |

||||||||

|

EC2 |

-0.170 |

-0.124 |

-0.168 |

0.263 |

0.257 |

0.209 |

0.595 |

1 |

|||||||

|

EC3 |

-0.176 |

-0.129 |

-0.174 |

0.273 |

0.267 |

0.217 |

0.617 |

0.573 |

1 |

||||||

|

SP1 |

-0.093 |

-0.068 |

-0.092 |

0.236 |

0.231 |

0.187 |

0.359 |

0.333 |

0.345 |

1 |

|||||

|

SP2 |

-0.081 |

-0.060 |

-0.080 |

0.205 |

0.201 |

0.163 |

0.312 |

0.290 |

0.169 |

0.614 |

1 |

||||

|

SP3 |

-0.083 |

-0.061 |

-0.082 |

0.209 |

0.204 |

0.166 |

0.318 |

0.295 |

0.306 |

0.625 |

0.544 |

1 |

|||

|

Sex |

0.058 |

0.043 |

0.058 |

-0.220 |

-0.215 |

-0.175 |

-0.172 |

-0.160 |

-0.165 |

-0.075 |

-0.065 |

-0.067 |

1 |

||

|

Age |

0.032 |

0.023 |

0.031 |

0.004 |

0.004 |

0.003 |

-0.135 |

-0.125 |

-0.130 |

-0.099 |

-0.087 |

-0.088 |

- |

1 |

|

|

Education Level |

-0.028 |

-0.021 |

-0.028 |

-0.087 |

-0.085 |

-0.069 |

-0.098 |

-0.091 |

-0.094 |

-0.185 |

-0.161 |

-0.164 |

-0.051 |

-0.133 |

1 |

Source: CIS 3298 Survey, calculated by the author using the WLSM estimator.