The Four Employment Trajectories of Mothers in Spain: Differences by Social Class

and Use of Parental Leaves

Las cuatro trayectorias laborales de las madres en España:

diferencias por clase social y uso de los permisos parentales

Victoria Bogino and Teresa Jurado-Guerrero

|

Key words

Sequence Analysis

- Work-life Balance

- Social Stratification

- Maternity

- Parental Leaves

- Employment Trajectories

|

Abstract

This article analyses the employment trajectories of the 1968-1978 cohorts of mothers, the factors influencing their employment relationship during family formation and their occupation towards the end of their fertile stage. The 2018 Fertility Survey provided the basis for a sequence analysis that revisited earlier findings on the polarisation of women in Spain and yielded four types of employment trajectories: secure employment, uncertain employment, intermittent employment and withdrawal from employment. As we were able to include partner characteristics in the regression models, we observed a social stratification of these trajectories by educational attainment and homogamous matching, which produced a social scarring effect. Greater access to maternity leave did not prevent this effect, but it decreased the likelihood of intermittent employment trajectories.

|

|

Palabras clave

Análisis de secuencias

- Conciliación

- Estratificación social

- Maternidad

- Permisos parentales

- Trayectorias laborales

|

Resumen

Este artículo analiza las trayectorias laborales de las cohortes de madres de 1968-1978, los factores que influyen en su vinculación laboral durante la formación familiar y en su ocupación hacia el final de la etapa fértil. La Encuesta de Fecundidad de 2018 permite realizar un análisis de secuencias que revisa los hallazgos previos de la polarización de las mujeres en España y arroja cuatro tipos de trayectorias laborales: vinculación segura, incierta, intermitente y desvinculación. Al poder incluir las características de la pareja en los modelos de regresión, observamos una estratificación social de esas trayectorias según el nivel educativo y un emparejamiento homógamo, que producen un efecto cicatriz de clase social. El mayor acceso al permiso de maternidad no evita este efecto, pero disminuye la probabilidad de tener trayectorias laborales intermitentes.

|

Citation

Bogino, Victoria; Jurado-Guerrero, Teresa (2025). “The Four Employment Trajectories of Mothers in Spain: Differences by Social Class and Use of Parental Leaves”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 192: 67-86. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.192.67-86)

Victoria Bogino: Universidad Complutense de Madrid | victoria.bogino@ucm.es

Teresa Jurado-Guerrero: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia | tjurado@poli.uned.es

Introduction

Sociological research has demonstrated that motherhood marks a turning point in the life course and negatively affects women’s relationship with employment. Many mothers encounter significant challenges in balancing work and family life, often reducing their working hours or exiting the labour market altogether (Sánchez-Mira and O’Reilly, 2019; Anxo et al., 2007). This, in turn, heightens the risk of in-work and child poverty in households with minors (Lanau and Lozano, 2024). Examining women’s working lives in relation to motherhood is crucial for understanding how they manage to balance work and family responsibilities over the long term.

In Spain, longitudinal analyses of employment trajectories remain scarce. Among the few studies available, the article by Davia and Legazpe (2014) is particularly noteworthy. Their study used sequence analysis applied to data from the 2006 Fertility Survey, which focused solely on Spanish-born mothers. It traced their trajectories from the age of sixteen to the age of thirty-five, only identifying the categories of “employed”, “non-employed” and “number of children”. Additionally, several pieces of research can be found based on cross-sectional data and constructed fictitious cohorts (Garrido, 1993; Dueñas-Fernández and Moreno-Mínguez, 2017), alongside research examining employment transitions after motherhood (Quinto, 2020; Lapuerta, 2012; Gutiérrez-Domènech, 2005). These studies highlighted that the extent to which motherhood affects employment trajectories depends on both individual factors (particularly, educational attainment) and institutional factors (such as parental leave policies). However, they did not consider immigrant mothers or employment trajectories before motherhood.

Although research has examined the impact of maternity on women’s employment trajectories, there remains a significant gap in our understanding of how work-life balance trajectories differ by social class, and whether this factor, in turn, shapes the social stratification of mothers towards the end of their childbearing years, when caregiving responsibilities tend to decrease. The class-based dimension of work-family balance is beginning to receive attention in studies on the organisation of paid and unpaid work within couples (Pailhé, Robette and Solaz, 2013; Sánchez-Mira, 2020; Deuflhard, 2023; López-Rodríguez and Gutiérrez-Palacios, 2023), yet it is still relatively underexplored in the literature. Most extant studies in Spain on employment transitions or sequences around motherhood have considered the mother’s level of education or occupation, but not those of her partner (Gutiérrez-Domènech, 2005; Lapuerta, 2012; Dueñas-Fernández and Moreno-Mínguez, 2017; Davia and Legazpe, 2014). There is also little research exploring the relationship between the use of parental leave and the types of employment trajectories followed by mothers (Kunze, 2022).

The aim of this analysis is to review the existing knowledge about the types of employment trajectories of mothers throughout their fertile period in Spain and to analyse the factors that influence their employment relationship and their occupation at the end of this stage. This was done by using retrospective data from the 2018 Fertility Survey to look at mothers born between 1968 and 1978 from the age of twenty to the age of forty. The following questions were asked: 1) What are the employment trajectory patterns of these mothers?; 2) How are they associated with their and their partners’ education level?; 3) To what extent does the use of parental leave policies allow for a stronger employment relationship?; 4) Which occupations do mothers enter after relatively uninterrupted employment trajectories, and how do their partners’ occupation influence this?

The added value of adopting a longitudinal methodological perspective and a multi-level theoretical approach (which encompasses the individual, the partner and the broader normative context) in this study is fourfold. First, it revisits previous findings on women’s working-life courses during the core years of family formation, incorporates immigrant mothers and uncovers a wider range of employment trajectories, beyond mere continuity in or withdrawal from employment. Second, it includes data on both mothers’ and their partners’ educational attainment, highlighting how this factor shapes the social stratification of mothers’ employment trajectories. Third, it investigates the relationship between the use of maternity leave, reduced working hours and childcare leave of absence, on the one hand, and mothers’ ability to sustain a more or less stable employment relationship, on the other. Lastly, it analyses occupational stratification towards the end of mothers’ childbearing years, in light of their employment trajectories and their partners’ occupations.

Theoretical framework and hypotheses

Some of the theories that seek to explain the division of labour between men and women are concerned with the relevance of “absolute and relative resources”, whereas others focus on how we construct “gender” (Domínguez-Folgueras, 2022). According to the former, employment and fertility choices are made on the basis of human capital and its current or expected returns, which shape the opportunity cost of withdrawing from employment. According to the second, gender-differentiated socialisation processes begin to operate in childhood, reinforced by cultural mandates in everyday interaction; hence, gender relations are constructed based on what each person thinks is expected of them as a man or a woman. On the whole, the performance of personal resources in the labour market depends not only on their purely transactional value, but also on how gender relations are constructed within couples or in the family environment in the case of single-parent families. Thus, women’s employment relationship is influenced not only by job opportunities, but also by maternal and paternal expectations about how to care for a child. The way families combine and divide work-family responsibilities may therefore differ among women depending on whether they have higher or lower educational attainment, based on their arrangements with their partner and also according to their cultural and institutional context (Grunow and Veltkamp, 2016; Castro et al., 2018).

Socially stratified patterns of work-life balance

Difficulties in securing stable employment and accessing housing can delay emancipation and family formation in Spain. This is the case both for people living in situations of precariousness and for those in privileged social groups, although the gap between the desired number of children and actual fertility is a problem only for the middle classes (Castro-Torres and Ruiz-Ramos, 2024). Other studies on the transition to the first child have shown the importance of these relationships between employment, housing and family formation (Alderotti et al., 2021; González and Jurado-Guerrero, 2006), as well as the significance of access to employment in relation to economic independence for women of more recent generations compared to women from previous generations (Rey, Grande and García-Gómez, 2022). Additionally, the delay in the average age at first and second births, as well as infertility, is becoming more uniform across educational strata, as women from middle- and lower-income backgrounds are also deferring childbirth until later in life or foregoing it entirely (Reher and Requena, 2019).

When previous analyses have addressed the situation upon the birth of the first child, they have identified patterns of polarisation in mothers’ employment trajectories. In the context of Spain, these patterns have been referred to as “two women’s biographies” (Garrido, 1993), the “exit or full-time model” (Anxo et al., 2007) or the “polarised model” (Sánchez-Mira and O’Reilly, 2019). These studies found that low educational attainment correlated with work-life balance trajectories characterised by long-term withdrawal from employment and high fertility rates, but also with low labour market participation and low fertility trajectories (Davia and Legazpe, 2014). Both trajectories were more prevalent among less educated women, as they had a lower opportunity cost of withdrawing from employment than more educated women.

The segmentation of the Spanish labour market also led to “balkanised” patterns of work-life balance in 2007 and 2012, characterised by higher rates of withdrawal from employment among women employed in semi-skilled or unskilled manual occupations, in agricultural work, or among those with no prior work experience (Sánchez-Mira, 2020). Similarly, immigrant women with low levels of education were particularly affected by this type of segmentation, as they were more likely than native-born women to be economically inactive or to interrupt their employment to take on domestic tasks, and less likely to engage in part-time work or to outsource care to relatives or private professional services (Sánchez-Domínguez and Guirola, 2021).

Within couples, a more traditional division of labour has also been observed among men and women when both have a lower level of education, as well as in cases where the man has a higher level of education or occupational status than their partner (Pailhé, Robette and Solaz, 2013, López-Rodríguez and Gutiérrez-Palacios, 2023). However, women with higher human capital were more likely to remain in employment throughout the life cycle, regardless of their partner’s level of education (Pailhé, Robette and Solaz, 2013). Thus, the dual family model, in which both partners are in paid employment, has been growing in recent years (Sánchez-Mira, 2020; González, 2023). The main leap towards this model, both quantitatively and qualitatively, was taken by women born between 1971 and 1975 (López-Rodríguez and Gutiérrez-Palacios, 2023). The likelihood of belonging to a household in which both partners work full-time has been found to double for women who are small business owners, managers or professionals, and even to increase significantly for those employed as technicians or clerical staff. However, this decreased for female manual workers and for those whose partner was a manual worker (Sánchez-Mira, 2020). Along these lines, Deuflhard’s (2023) research showed that social class increasingly influenced gendered decisions about paid and unpaid work, because the increase in jobs with atypical hours is concentrated among working-class couples, which reinforces the gendered specialisation of work. The effect of the need for family income is subject to the opportunity cost effect, as the potential wage does not cover the costs of childcare and discourages mothers’ continuity of employment (England, 2010).

Access to and use of parental policies

The institutional and cultural context also influences employment opportunities, the balance between work and care, and the hegemonic moral imperatives directed at women and men. In Spain, the 1960s cohorts were little affected by the initial implementation of parental policies. In contrast, access to employment for women born from the 1970s onwards coincided with the development of some work-life balance measures in the late 1990s and early 2000s, and with the approval of the Ley de Igualdad (Equality Act) in 2007 (López-Rodríguez and Gutiérrez-Palacios, 2023).

Parental leave policies are initiatives aimed at helping workers achieve a better balance and joint responsibility between paid work and care duties (Castro et al., 2018). In practice, these measures have had a strong gender bias, as they have primarily been aimed at promoting employment among mothers, given their historically low labour market participation and the career gaps caused by maternity (Burnett et al., 2010). Employment conditions and gender values can also profoundly influence access to and use of these policies. Mothers with precarious jobs and low wages often face major difficulties in accessing these policies. Conversely, mothers in higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs potentially have greater access, but they may be reluctant to use parental leave in the private sector due to pressures to conform to work expectations (Moran and Koslowski, 2019).

The design of maternity leave has affected mothers’ employment, particularly depending on its length: very short and very long leave discourages mothers from returning to employment (Kunze, 2022). Women who make use of maternity leave in Spain tend to do so for the entire legally prescribed duration, which amounts to approximately 113 days (16.1 weeks) for women receiving contributory benefits, and 42.5 days (6.1 weeks) for those receiving non-contributory benefits (Meil, Romero-Balsas and Rogero-García, 2020). However, not all mothers who were active in the labour market have been able to avail themselves of maternity leave. Some are not eligible for this benefit, such as women who are self-employed or who work as employees in the private sector and, above all, those who are employed on a temporary contract or without a contract at all. These circumstances are also more common among those mothers with lower levels of education and income (Meil, Romero-Balsas and Rogero-García, 2020). The uptake of paternity leave by men also constitutes a significant factor: as the use of paternity leave increases, the motherhood penalty decreases (Gorjón and Lizarraga, 2024; Dearing, 2016).

Leave of absence and reduced working hours for childcare are also measures to support mothers to remain in employment, but these are not accompanied by a loss of earnings allowance. Most mothers in Spain who take a childcare leave of absence do so after their maternity leave and for up to one year, at which point the employer is obliged to offer them a job of equivalent status. Reduced working hours for care purposes allows workers to reduce their working hours (from one eighth to half) until their child reaches the age of twelve, while keeping their job. Data show that most mothers use this leave for a period of 36 months, with a reduced daily time of 2.6 hours on average (Meil, Romero-Balsas and Rogero-García, 2020; Domínguez-Folgueras, González and Lapuerta, 2022). However, only certain employees are able to use them: mainly mothers with higher education who are on a full-time permanent contract, with a longer period of service, higher income and working in the public sector or in large companies, who enjoy high levels of protection thanks to collective bargaining agreements. Reduced working hours are also often used by those who have more favourable attitudes towards childcare versus paid work and have a partner with a stable job (Lapuerta 2012; Meil, Romero-Balsas and Rogero-García, 2020).

Among mothers who take leave from full-time employment, half tend to return to full-time employment (55 %), a smaller proportion reduce their working hours (35 %), and an even a smaller proportion leave or are made redundant (10 %), with the corresponding negative consequences for their income, career, contribution record and future pension. In contrast, among mothers who opt for reduced working hours, the majority tend to return to full-time employment (72 %), around a quarter leave employment (22 %) and an even smaller proportion seek part-time employment (7 %) (Meil, Romero-Balsas and Rogero-García, 2020: 317).

Based on the contributions found in the literature review, we propose to examine three main hypotheses. First, we assume that (H1) mothers without tertiary education are less likely to follow continuous employment trajectories, regardless of the education level of their partners (prevalence of individual resources). Secondly, we deduce that (H2) mothers who do not have continuous employment trajectories make less use of parental policies, as a result of a vicious circle whereby they have more barriers to access and this, in turn, makes it more difficult for them to have continuity of employment (Matthew effect). Finally, we aim to understand whether employment trajectories during the family formation stage (from the ages of twenty to forty years old) generate inequalities in occupational stratification towards the end of the fertile period (from forty to fifty years of age); and, more specifically, whether a social scarring effect occurs, in the sense that (H3) employment trajectories without a continuous employment relationship are more likely to result in lower occupational categories, and whether these categories are more commonly associated with women whose partners are working class.

Data and methods

The analysis uses data from the 2018 Fertility Survey (EF2018) of the National Statistics Institute (INE). This survey is nationally representative and has comprehensive information on the fertility, relationship and work histories of women of childbearing age. The opportunity to understand the education level and occupation of the respondent’s partner is one of its main advantages compared to similar surveys with longitudinal information. This study focuses on biological or adoptive mothers born between 1968 and 1978 who were observed on a monthly basis from their twenties to their forties. The final sample was made up of 3649 mothers.

The 2018 Fertility Survey allows for the reconstruction of employment trajectories on the basis of respondents’ employment status at two points in time. On the one hand, in 2018 and, on the other hand, the year when the respondent had her first job and the four subsequent jobs, if any. Thus, it provides fairly precise information on the timing of entry into the labour market and the subsequent years, as well as on the employment status in 2018 and the preceding years. This makes it possible to reconstruct employment trajectories both “forwards” (towards 2018) and “backwards” (from 2018 back), as the survey questionnaire collects data on when each employment status began. This reconstruction poses two challenges. First, information is only available for six jobs per mother at most, because the past employment history was limited to five (and the job held in 2018 was added). Second, questions were only asked about jobs of at least one year’s duration, except for the first job and the current job. If respondents had had more than five jobs prior to 2018, they were asked to indicate the first (of any duration) and the next four jobs of longer duration (at least one year). Information on employment status around each birth was used to better understand employment trajectories where information was missing, and the category “employed for less than twelve months or economically inactive” was created to cover information “gaps”. In this way, a clear distinction can be made between stable and more precarious employment trajectories, overcoming the employed/non-employed dichotomy presented by Davia and Legazpe (2014).

The methodological strategy consisted of two steps. Firstly, a sequence and cluster analysis was carried out to identify a typology of mothers’ employment trajectories. Secondly, multinomial logistic regression models were run to examine the factors influencing these trajectories during the family formation stage and in employment towards the end of the respondents’ childbearing life.

Step 1: Sequence and cluster analysis

A sequence analysis, based on the Optimal Matching Analysis (OMA) technique, and a cluster analysis, which used the Partitioning Around Medoids method (PAM) (Raab and Struffolino, 2022), were conducted to identify the different types of employment trajectories.

An employment status was assigned to each month of observation. For each job there were five possible statuses; however, by combining all available information, nine distinct statuses could be identified within the employment trajectories: 1) self-employed with employees; 2) self-employed with no employees; 3) salaried with a permanent contract; 4) salaried with a temporary contract equal to or longer than twelve months; 5) salaried without a contract; 6) unemployed (in 2018 and the previous months since its start); 7) always outside the labour force; 8) training or economic inactivity before first employment; and 9) employed for less than twelve months or economic inactivity.

Step 2: Multinomial logistic regression

After summarising the employment trajectories in the clusters, three multinomial logistic regression models were estimated. The first model estimated the probability of belonging to the clusters based on the education level of the mothers and their partners (lower secondary or below, upper secondary or vocational training, and university), controlling for the mother’s age at birth or adoption of the first child (under 25, 25 to 34, or 35 and over); the number of children (one, two, or three or more); and the country of birth (native-born, immigrants from countries with a higher GDP per capita than Spain, and immigrants from countries with a lower GDP per capita than Spain). The second model added the rate of mothers’ use of maternity leave (was not active; was active and did not take maternity leave; or was active and took maternity leave), and whether or not they took maternity leave or reduced their working hours to care for their child. It also controlled for the year of birth of the first child (before 1994; between 1995 and 2006; or in 2007 or later), in order to discern whether there was a difference between women who had become mothers before and after the implementation of the 1994 General Social Security Act and the 2007 Equality Act. Finally, the third model differed from the previous ones because it took the occupation of the mothers in 2018 (six occupational categories, unemployed, or out of the labour force) as a dependent variable and related it to the clusters of the different employment trajectories of the mothers, the occupation of their partner in 2018 (six occupational categories), or whether they were single parents; also controlling, as before, for the country of birth, the age of the mother at birth or adoption of the first child, the year of birth of the first child and the number of children. The descriptive data of the clusters according to the independent variables can be found in Table 1 in the Annex.

Results

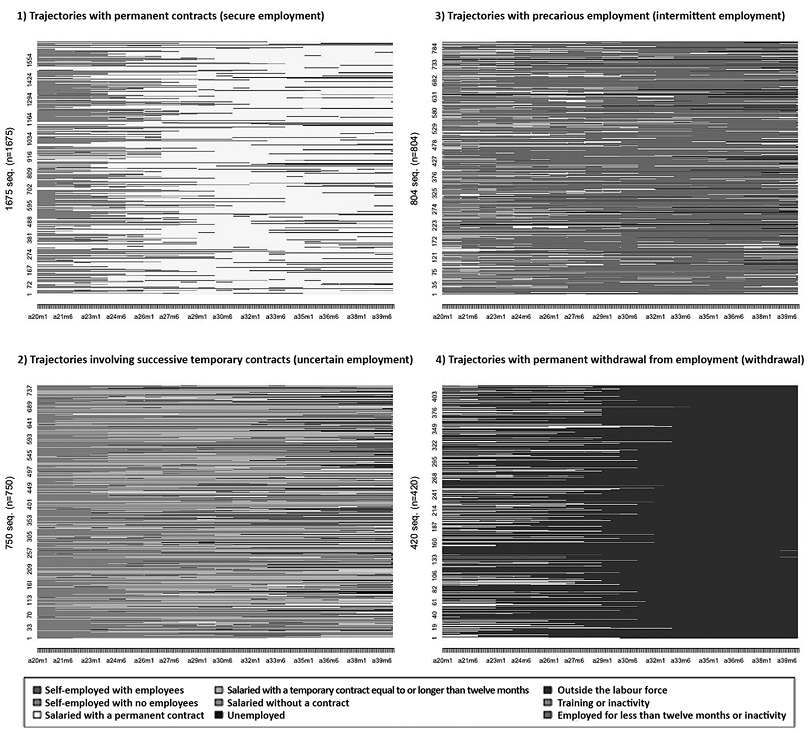

Figure 1 shows the graphs with the mothers’ employment trajectories represented as stacked horizontal bars. Each of these bars indicates a trajectory for each woman. The cluster analysis yielded four groups of trajectories. The first cluster contains trajectories where permanent contracts prevailed (“secure employment”, 45.9 %); the second cluster reflects trajectories with a succession of temporary contracts (“uncertain employment”, 20.6 %); the third cluster includes trajectories with greater job insecurity (“intermittent employment”, 22 %); and, finally, the fourth cluster contains trajectories of permanent withdrawal from employment up to 2018 (“withdrawal from employment”, 11.5 %).

In each of the graphs, the vertical axis shows the number of mothers belonging to each group and the horizontal axis indicates the age of the sequence, from twenty to forty years old. All the graphs show that most of the mothers had a period of training or economic inactivity before their first job, although there were also some cases of mothers who started working at a very young age or had always been outside the labour force.

As for the differences between the clusters, it can be seen that there are two fairly clear clusters (cluster 1 and 4) and two more diversified clusters (cluster 2 and 3). Among the first group, located at each end, cluster 1 includes mothers who combined a period of training with a period of permanent employment (lasting an average of thirteen years). In contrast, the last cluster reflects women who had withdrawn from the labour market for almost the entire observation period (around sixteen years on average). Among the clusters with the highest variability, cluster 2 includes women who, despite having been longer in training or economic inactivity before their first job (for six years on average), had long temporary contracts (for eight years on average); and cluster 3 contains women who mostly had a succession of short-term temporary contracts (for eleven years on average).

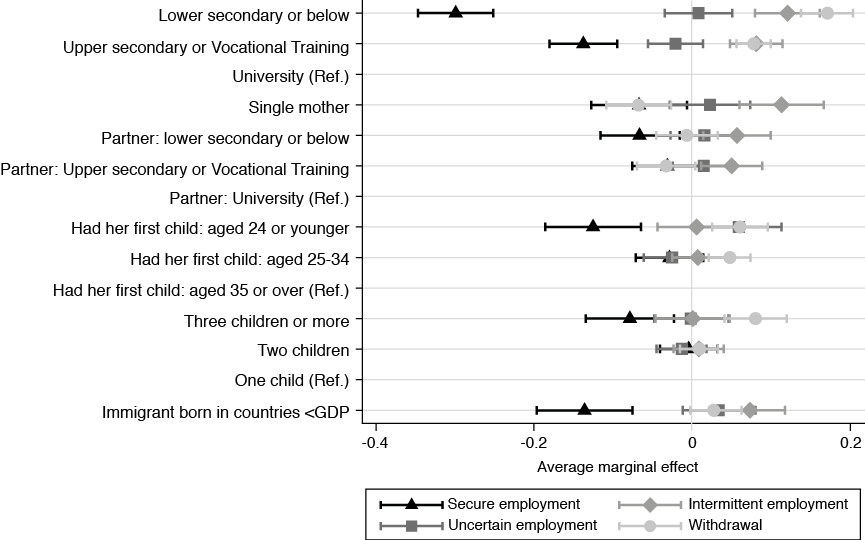

The results of the multinomial regression analysis are presented in terms of mean marginal effects with a 95 % confidence interval (Figures 2, 3 and 4). The first two multinomial regression models included the clusters of employment trajectories as the dependent variable. Mothers with continuous employment trajectories and a secure contractual relationship (secure employment) were chosen as the reference category, because we were interested in the characteristics of mothers who were less likely to have maintained employment over the twenty years of observation.

Figure 2 shows the results of the first model. This shows that mothers with uncertain employment trajectories, due to the chain of long-term temporary contracts, were the least distinguishable from those with secure employment trajectories with respect to the factors analysed, as shown by their positioning around 0 on the horizontal axis for almost all independent variables. It also highlights that the largest differences, between 7 and 30 percentage points on average (0.3 on the axis equals 30 %), were associated with mothers’ educational attainment. Compared to “university-educated” mothers, mothers with “lower secondary education or below” showed a significantly lower mean probability of having had secure employment (-30 %) and a higher mean probability of having had intermittent employment (12 %) or a trajectory marked by withdrawal from employment (17 %). Those with “upper secondary or vocational training” did not show as many differences from “university-educated” women in terms of the degree of their employment relationship; however, they had a lower mean probability of having secure employment (14 %) and a higher mean probability (8 %) of withdrawal from employment or of having had intermittent employment. The education level of their partner had less of an impact on mothers’ employment trajectories; particularly if their partner had “lower secondary education or below”, mothers were less likely to have had secure employment (-7 %) and more likely on average to have had an intermittent employment trajectory (6 %), compared to those with “university-educated” partners. This intermittent trajectory was also more likely to be found among mothers who had a partner with an education level of “upper secondary or vocational training” (5 %) and even more so among mothers who were single parents (11 %), compared to mothers whose partner was a “university graduate”. In turn, other events in the family cycle were seen to have significantly shaped employment trajectories. One of them was “first child born at age 24 or younger”, which decreased the mean probability of secure employment (-12 %) and increased the probability of withdrawal from employment (6 %) compared to “late first parenthood at age 35 or older”. Having three or more children also decreased the mean probability of secure employment p (-8 %) and increased the mean probability of withdrawal from employment (8 %), compared to having had “one child”. There were no significant differences between the number of children and the other types of employment trajectories when controlling for educational attainment, as in this model. “Having been born in a foreign country with a lower GDP per capita” than Spain also significantly reduced the mean probability of having had secure employment, compared to “similar native-born and foreign respondents” (-14 %). However, its average effect was smaller than having “lower secondary education or below” (-30 %). In this respect, there were certainly immigrants who compensated for the disadvantages that migration entails by having high levels of education or other relevant individual assets.

To sum up, among the factors included in this analysis, the most influential on mothers’ employment outcomes was the level of education they had attained. In relation to the first hypothesis, mothers without tertiary education were significantly less likely to follow “secure employment” trajectories than their more educated counterparts, regardless of their partners’ educational attainment. The latter factor decreased the likelihood of mothers having secure employment trajectories, and differed from the other types of trajectories, if their partner’s education level was “lower secondary or below” versus having “a university degree”. This confirmed the importance of individual opportunity costs.

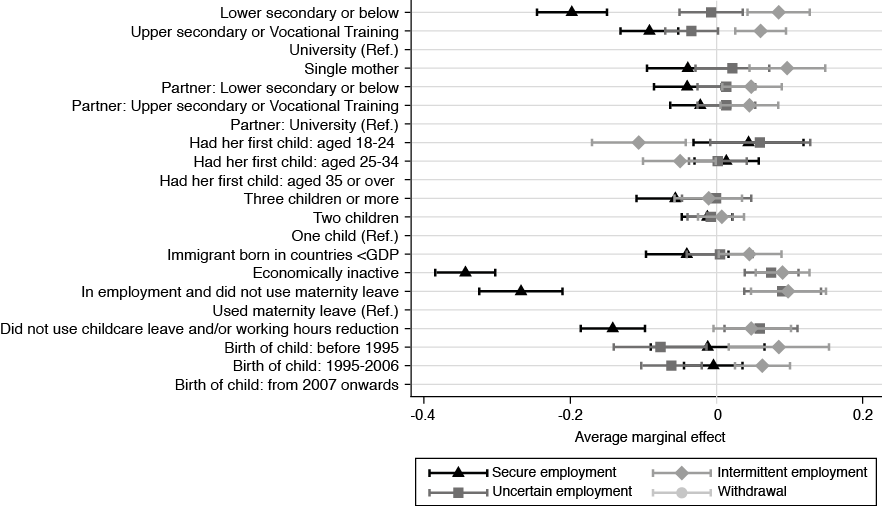

Figure 3 shows the results of the second model. It associates the context of parental leave policies and their use with different employment trajectories. The variables from the previous model were maintained, so their explanatory power increased (from Pseudo R2 0.062 to 0.13). Comparing the two models, the results for the common independent variables were similar, except that the effects of mothers’ educational attainment and country of birth diminished once variables on the periods when use and advancement of parental policies were introduced. Mothers who had their first child before and after the Ley General de la Seguridad Social (1994 Social Security Act) were more likely to have had intermittent employment trajectories (8.2 % and 6.2 % respectively), compared to mothers who had their first child after the 2007 Equality Act. This may be because it was more difficult to meet the previous contribution requirements for maternity leave. Among those who were economically active because they were employed or receiving unemployment benefit at the time of having their first child, some were unable to use maternity leave and this correlated with a significantly lower probability of having a secure employment trajectory (-27 %), but also with a higher probability of having an uncertain or intermittent employment trajectory or a withdrawal from employment trajectory (between 8-10 %), controlling for all other factors. The effect of not having used leave or reduced working hours for childcare was smaller and was especially related to a lower probability of having had a secure employment trajectory (-14 %).

In summary, in line with the second hypothesis, not having made use of parental leave was less closely associated with secure employment trajectories. This may reflect a bidirectional relationship, because mothers with trajectories characterised by greater withdrawal from employment found it more difficult to access work when they had their first child, and this in turn hindered them from continuing in the labour market.

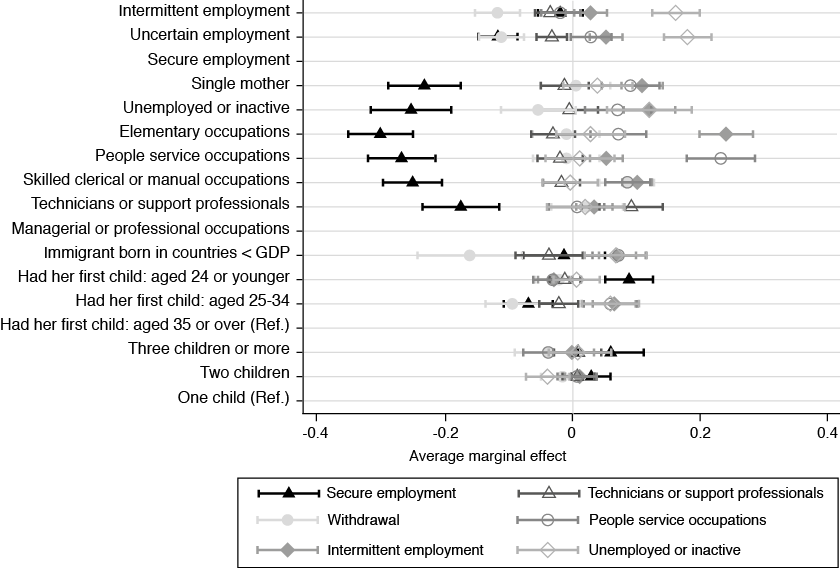

Figure 4 shows the results of the third model. This analysed whether employment trajectories during the family formation stage, from the ages of twenty to forty, generated inequalities in occupational stratification towards the end of the fertile period, when these mothers were between forty and fifty years old in 2018, and whether the mothers’ occupation was also influenced by their partner’s occupation, as shown in previous cross-sectional studies (Sánchez-Mira, 2020). To this end, we estimated the probability of mothers being in different occupations according to their type of employment trajectory, the occupation of their partner, or whether they were a single mother, also controlling for place of birth, age at first birth and number of children. Mothers with trajectories characterised by withdrawal from employment were not included, as they were all economically inactive in 2018.

First, regarding the type of employment trajectory, taking secure employment as a reference, mothers with “intermittent employment” or “uncertain employment” were more likely to be unemployed or economically inactive (16 % or 18 %, respectively) or in an “elementary occupation” (3 % or 5 %) towards the end of their childbearing life. Second, the effects of their partner’s job showed a remarkable occupational homogamy at that stage of the family cycle, because having a partner in “elementary occupations” increased the probability of also being in an “elementary occupation” (24 %) and so on for “people service occupations” (23 %) or “technical occupations” (9 %), all compared to having a partner in a “managerial or professional occupation”. Taking the latter category as a reference, it was also found that “single motherhood” was more related to “elementary occupations” and “people service occupations” (10 % and 9 %), which was in line with the increase in single motherhood among women with lower education levels (Garriga and Cortina, 2017). If a woman’s partner was unemployed or economically inactive, she was also more likely to be unemployed or economically inactive (12 %), which brings us back to the problem of poverty in households with minor children (Lanau and Lozano, 2024). The only exception to this occupational homogamy relationship was observed for couples in “skilled clerical or manual occupations”, which correlated with the woman being in the same occupation, but also in an “elementary occupation” or in “people service occupations” (8 %), which may have compensated for the low earnings of mothers in the latter occupations. Third, if the mother was born in a foreign country with a lower GDP than Spain, she was more likely to be in an “elementary occupation”, “unemployed” or “economically inactive” (7 %) in 2018, regardless of the employment trajectory she had followed. Four, the mother having had her first child under the age of twenty-five was also associated with her being in an “elementary occupation”, “unemployed” or “economically inactive” (9 %). Finally, if the mother had three or more children, she was more likely to hold a managerial or professional occupation (5 %), which shows an alternative pathway to inactivity in order to have a large family (not included in this model).

In summary, in relation to the third hypothesis, a “social scarring effect” was observed in mothers with “intermittent or uncertain” employment trajectories, in the sense that they were more likely to be in “elementary occupations”, in “people service occupations”, “unemployed” or “outside the labour force”. Moreover, these mothers, more often than not, had partners in “elementary occupations” or in “people service occupations” and, to a lesser extent, who were “unemployed” or “inactive”, or they themselves were single mothers.

Conclusions

This article has analysed the patterns of mothers’ employment trajectories in Spain, the factors that influenced their employment relationship during family formation and their occupation towards the end of their childbearing years. Retrospective data from the 2018 Fertility Survey were used to look at mothers born between 1968-1978 when they were between the ages of twenty to forty years old.

The results of the sequence and cluster analysis revealed four types of employment trajectories. The first group included trajectories with permanent contracts (“secure employment”, 45.9 %), the second reflected a chain of temporary contracts (“uncertain employment”, 20.6 %), the third showed trajectories of job insecurity (“intermittent employment”, 22 %) and the fourth group was characterised by trajectories of permanent withdrawal from employment (“withdrawal from employment”, 11.5 %).

Among the factors influencing mothers’ employment relationship, educational attainment was the strongest predictor of employment trajectories. The first hypothesis of the “prevalence of individual resources” was only partially validated, in terms of the high predictive capacity of their educational attainment on their employment trajectories. In relation to the first hypothesis, mothers without tertiary education were significantly less likely to have had “secure employment” trajectories than their more educated peers, regardless of their partners’ educational attainment. By contrast, having a partner with lower secondary education or below did have an influence compared to having a partner with a university degree. The opportunity cost therefore outweighed the effect of the need for household income (England, 2010). In addition, having three or more children, becoming a mother at an early age, and being an immigrant from a country with a lower GDP than Spain predicted trajectories of withdrawal from employment, regardless of education level.

The second hypothesis, concerning the Matthew Effect of parental policies, was fully confirmed: mothers who were in employment at the time of their first child’s birth but did not make use of maternity leave, leave of absence or reduced working hours for childcare were less likely to follow secure employment trajectories. This may indicate a bidirectional relationship, as mothers who experienced greater withdrawal from employment likely faced more barriers to employment when they had their first child, which in turn made it more difficult for them to remain in the labour market. This relationship was less pronounced among mothers who had their first child after the 2007 Equality Act was passed, as they benefited from improved access to maternity leave and from the use of childcare leave or reduced working hours, regardless of their educational attainment. This underlines the role of statutory leave—particularly maternity leave—in facilitating work-family balance. Additionally, the relatively short duration of maternity leave in Spain did not appear to discourage mothers from returning to work (Kunze, 2022).

The third hypothesis was partially corroborated. There was a “social scarring effect” for mothers with intermittent or uncertain employment trajectories as they approached the end of their childbearing years (between the ages of forty and fifty) in 2018, because they were at high risk of being unemployed or outside the labour force, or of having elementary or people service occupations. Similarly, these occupational categories to which mothers belonged were associated with having the same occupational categories as their partners. An exception to this relationship of occupational homogamy occurred when these mothers’ partners were employed as clerical or skilled manual workers. However, having an unskilled, working class partner was the determinant that most increased the likelihood that the mother was also in this class. This may indicate that, apart from educational attainment and parental leave policies, the couple’s work schedules were very important. When they had long or atypical working hours, they conflicted with children’s school times, made work-life balance even more difficult and restricted mothers’ participation in the labour market. This may therefore reinforce the sexual division of labour, as Deuflhard (2023) showed for the case of Germany. Another important finding was the high probability of having had intermittent employment trajectories for mothers without a partner and of being in elementary and people service occupations in 2018, which made the high risk of child poverty in single-mother families understandable.

It can therefore be concluded that parental policies and work schedules should be modified simultaneously to facilitate work-life balance across all social classes and family circumstances. On the one hand, there is a need to reduce the barriers to parental leave in general, and to maternity leave in particular, for certain employment situations: self-employment, domestic service, precarious jobs that do not allow for appropriate social security payments, unemployment without contributory benefits and informal jobs. Although the contribution requirements have been relaxed, it is still necessary to further ease the criteria in order to include these types of employment as equivalent to being registered with the Social Security System, thereby facilitating access to maternity leave. On the other hand, there is a need to improve ways of synchronising employment and care times and to ensure wages that avoid in-work poverty. This would enable a move towards a dual-earner-dual-carer model (Gornick and Meyers, 2003) between mothers and fathers from different social strata, thus decreasing economic and time poverty for care.

Finally, this study has certain limitations. The influence of the use of parental leave on the type of employment relationship cannot be accurately estimated, since its cause, as indicated above, is likely to be bidirectional. The 2018 Fertility Survey also prevented longitudinal analyses in general from being more precise. It did not include jobs held for less than one year and did not distinguish between part-time and full-time employment. Moreover, it only recorded the employment and unemployment status in 2018, but failed to capture it systematically over the whole observation period. Although the dataset included information on the number of months mothers had taken maternity leave and childcare-related leave of absence for each of their children, it did not contain data regarding reduced working hours for caregiving purposes. It also did not make it possible to monitor the specific start and end month in which mothers had taken parental leave. Hopefully, the next Fertility Survey will overcome these limitations. Nevertheless, this study has provided evidence on the importance of paying attention to social class and the use of parental leave policies when analysing mothers’ long-term employment relationships.

Bibliography

Alderotti, Giammarco; Vignoli, Daniele; Baccini, Michela and Matysiak, Anna (2021). “Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A meta-analysis”. Demography, 58(3): 871-900. doi: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Anxo, Dominique; Fagan, Colette; Cebrian, Inmaculada and Moreno, Gloria (2007). “Patterns of Labour Market Integration in Europe - A life Course Perspective on Time Policies”. Socio-Economic Review, 5(2): 233-260. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwl019

Burnett, Simon; Gatrell, Caroline; Cooper, Cary and Sparrow, Paul (2010). Fatherhood and Flexible Working: A Contradiction in Terms? In: S. Kaiser; M. J. Ringlstetter; M. Pina e Cunha and D. R. Eikhof (eds.). Creating Balance? International Perspectives on the Work-Life Integration of Professionals. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer.

Castro, Teresa; Martín, Teresa; Cordero, Julia and Seiz, Marta (2018). The Challenge of Low Fertility in Spain. In: Informe España 2018 (pp. 165-232). Cátedra José María Martín Patino de la Cultura del Encuentro.

Castro-Torres, Andrés and Ruiz-Ramos, Carlos (2024). “Clases sociales y transición a la vida adulta en España”. Perspectives Demogràfiques, 34: 1-4. doi: 10.46710/ced.pd.esp.34

Davia, María and Legazpe, Nuria (2014). “Female Employment and Fertility Trajectories in Spain: An Optimal Matching Analysis”. Work, Employment and Society, 28(4): 633-650. doi: 10.1177/0950017013500117

Dearing, Helene (2016). “Gender Equality in the Division of Work: How to Assess European Leave Policies Regarding Their Compliance with an Ideal Leave Model”. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(3): 234-247. doi: 10.1177/09589287166429

Deuflhard, Carolin (2023). “Who Benefits from an Adult Worker Model? Gender Inequality in Couples’ Daily Time Use in Germany Across Time and Social Classes”. Socio-Economic Review, 21(3): 1391-1419. doi: 10.1093/ser/mwac065

Dueñas-Fernández, Diego and Moreno-Mínguez, Almudena (2017). “Mujeres, madres y trabajadoras. Incidencia laboral de la maternidad durante el ciclo económico”. Revista de Economía Laboral, 14(2): 66-103. doi: 10.21114/rel.2017.02.04

Domínguez-Folgueras, Marta (2022). “It’s About Gender: A Critical Review of the Literature on the Domestic Division of Labour”. Journal of Family Theory Review, 14(1): 79-96. doi: 10.1111/jftr.12447

Domínguez-Folgueras, Marta; González, M. José and Lapuerta, Irene (2022). “The Motherhood Penalty in Spain: The Effect of Full- and Part-Time Parental Leave on Women’s Earnings”. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 29(1): 164-189.

England, Paula (2010). “The Gender Revolution”. Gender & Society, 24(2): 149-166. doi: 10.1177/0891243210361475

Fasang, Anette and Aisenbrey, Silke (2021). “Uncovering Social Stratification: Intersectional Inequalities in Work and Family Life Courses by Gender and Race”. Social Forces, 101(2): 575-605. doi: 10.1093/sf/soab151

Garrido, Luis (1993). Las dos biografías de la mujer en España. Madrid: Instituto de la Mujer.

Garriga, Anna and Cortina, Clara (2017). “The Change in Single Mothers’ Educational Gradient over Time in Spain”. Demographic Research, 36: 1859-1888. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.61

González, María José and Jurado-Guerrero, Teresa (2006). “Remaining Childless in Affluent Economies: A Comparison of France, West Germany, Italy and Spain, 1994-2001”. European Journal Population, 22: 317-352. doi: 10.1007/s10680-006-9000-y

González, María José (2023). Patriarchy, Power and Women’s Independence: The Transformation of Marriage and Families in Spain, 1976-2020. In: L. E. Delgado and E. Ledesma (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Twentieth- and Twenty-First Century Spain: Ideas, Practices, Imaginings. Routledge.

Gorjón, Lucía and Lizarraga, Imanol (2024). Family-friendly policies and Employment Equality: An Analysis of Maternity and Paternity Leave Equalization in Spain. ISEAK Working Paper, 2024/3.

Gornick, Janet and Meyers, Marcia (2003). Families That Work: Policies for Reconciling Parenthood and Employment. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Grunow, Daniela and Veltkamp, Gerlieke (2016). Institutions as Reference Points for Parents-to-be in European Societies: A Theoretical and Analytical Framework. In: D. Grunow and M. Evertsson (eds.). Couples’ Transitions to Parenthood. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gutierrez-Domènech, María (2005). “Employment Transitions after Motherhood in Spain”. Review of Labour Economics & Industrial Relations. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9914.2005.00313.x

Kunze, Astrid (2022). “Parental Leave and Maternal Labor Supply”. IZA World of Labor.

Lanau, Alba and Lozano, Mariona (2024). “Pobres con empleo: un análisis de transiciones de pobreza laboral en España”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 186: 83-102. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.186.83-102

Lapuerta, Irene (2012). Employment, Motherhood, and Parental Leaves in Spain. González López, María José (dir.), Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. [Doctoral thesis]. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10803/81708, access January 10, 2025.

López-Rodríguez, Fermín and Gutiérrez-Palacios, Rodolfo (2023). “Cambios en la composición educativa y equilibrios de empleo de las parejas en España”. Revista Española de Sociología, 32(3), a180. doi: 10.22325/fes/res.2023.180

Meil, Gerardo; Romero-Balsas, Pedro and Rogero-García, Jesús (2020). “Los permisos para el cuidado de niños/as: evolución e implicaciones sociales y económicas”. Spain 2020 Report. Madrid: Universidad Pontificia Comillas, J. M. Martín Patino Chair.

Moran, Jessica and Koslowski, Alison (2019). “Making Use of Work-Family Balance Entitlements: How to Support Fathers with Combining Employment and Caregiving”. Community, Work & Family, 22(1): 111-128. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2018.1470966

Pailhé, Ariane; Robette, Nicolas and Solaz, Anne (2013). “Work and Family Over the Life Course. A Typology of French Long-lasting Couples Using Optimal Matching”. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 4(3): 196-217. doi: 10.14301/llcs.v4i3.250

Quinto, Alicia de; Hospido, Laura and Sanz, Carlos (2020). “The Child Penalty in Spain”. Banco de España, Occasional Paper.

Raab, Marcel and Struffolino, Emanuela (2022). Sequence Analysis. Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences. New York: SAGE.

Reher, Davis and Requena, Miguel (2019). “Childlessness in Twentieth-Century Spain: A Cohort Analysis for Women Born 1920-1969”. European Journal Population, 35: 133-160. doi: 10.1007/s10680-018-9471-7

Rey, Alberto del; Grande, Rafael and García-Gómez, Jesús (2022). “Transiciones a la maternidad a través de las generaciones. Factores causales del nacimiento del primer hijo en España”. Revista Española de Sociología, 31(2), a108. doi: 10.22325/fes/res.2022.108

Sánchez-Domínguez, María and Guirola, Luis (2021). “The Double Penalty: How Female Migrants Manage Family Responsibilities in the Spanish Dual Labour Market”. Journal of Family Research, 33(2): 509-540. doi: 10.20377/jfr-497

Sánchez-Mira, Núria (2020). “Work-family Arrangements and the Crisis in Spain: Balkanised Gender Contracts?”. Gender, Work & Organization, 27(6): 944-970. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12417

Sánchez-Mira, Núria and O’Reilly, Jaqueline (2019). “Household Employment and the Crisis in Europe”. Work, Employment and Society, 33(3): 422-443. doi: 10.1177/0950017018809324

ANNEX

Table 1. Descriptive data of clusters according to independent variables (%)

|

Independent variables

|

Secure employment relationship

|

Uncertain employment relationship

|

Intermittent employment relationship

|

Withdrawal from employment

|

N Total

|

|

Age at birth of first child

|

|

Under 25 years old

|

9.8

|

22.5

|

20.7

|

30.3

|

640

|

|

From 25 to 34 years old

|

64.0

|

55.8

|

61.5

|

60.8

|

2,230

|

|

35 years old and over

|

26.2

|

21.7

|

17.7

|

8.9

|

779

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,649

|

|

Mother’s education level

|

|

Lower secondary or below

|

15.2

|

30.2

|

35.1

|

52.5

|

953

|

|

Upper secondary or vocational training

|

38.1

|

37.0

|

43.4

|

37.2

|

1,379

|

|

University

|

46.7

|

32.8

|

21.5

|

10.3

|

1212

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,544

|

|

Partner’s education level

|

|

Lower secondary or below

|

24.2

|

32.8

|

35.9

|

49.5

|

1,113

|

|

Upper secondary or vocational training

|

34.7

|

33.0

|

33.4

|

28.1

|

1,180

|

|

University

|

31.0

|

21.3

|

14.6

|

14.5

|

834

|

|

Single mother

|

10.2

|

12.9

|

16.1

|

7.9

|

417

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,544

|

|

Type of country of birth

|

|

Native-born and immigrant born >= GDP Spain

|

94.5

|

89.4

|

88.0

|

87.2

|

3,232

|

|

Immigrants born in countries

< GDP Spain

|

5.5

|

10.6

|

12.0

|

12.8

|

312

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,544

|

|

Number of children

|

|

One child

|

32.7

|

32.1

|

31.1

|

23.4

|

1,105

|

|

Two children

|

57.3

|

53.7

|

56.2

|

53.0

|

1,979

|

|

Three or more children

|

10.0

|

14.1

|

12.7

|

23.6

|

460

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,544

|

|

Use of maternity leave for 1st child

|

|

Mother in employment and took it

|

80.5

|

47.4

|

42.6

|

15.8

|

2,057

|

|

Mother in employment and did not take it

|

5.9

|

12.9

|

13.7

|

11.1

|

341

|

|

Mother did not take it as she was not in employment

|

13.6

|

39.7

|

43.7

|

73.2

|

1,146

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,544

|

|

Use of other statutory leaves for 1st child

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Used childcare leave of absence or reduced working hours

|

25.2

|

8.5

|

7.8

|

*

|

545

|

|

Did not use childcare leave of absence or reduced working hours

|

74.8

|

91.5

|

92.2

|

97.5

|

2,999

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

97.5

|

3,544

|

|

Year of birth of first child

|

|

Before 1995

|

7.0

|

14.8

|

15.4

|

21.4

|

428

|

|

1995-2006

|

52.6

|

51.6

|

61.5

|

63.3

|

1,969

|

|

2007 or later

|

40.5

|

33.5

|

23.1

|

15.3

|

1,147

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,544

|

|

Mother’s occupation in 2018

|

|

Managerial, professional

|

25.6

|

19.6

|

9.7

|

-

|

637

|

|

Technicians, support professionals

|

10.6

|

6.3

|

6.2

|

-

|

267

|

|

Clerical, skilled manual

|

29.1

|

15.0

|

15.4

|

-

|

704

|

|

People services occupations

|

14.7

|

14.4

|

19.9

|

-

|

500

|

|

Elementary occupations

|

7.0

|

12.9

|

16.1

|

-

|

333

|

|

Unemployed or inactive

|

13.1

|

31.7

|

32.6

|

-

|

697

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

-

|

3,138

|

|

Partner’s occupation in 2018

|

|

Managerial, professional

|

22.6

|

16.1

|

12.3

|

13.5

|

583

|

|

Technicians, support professionals

|

10.4

|

7.8

|

6.5

|

4.4

|

278

|

|

Clerical, skilled manual

|

29.6

|

25.0

|

27.6

|

29.1

|

880

|

|

People services occupations

|

11.2

|

10.9

|

11.9

|

9.6

|

355

|

|

Elementary occupations

|

10.4

|

16.1

|

14.6

|

20.2

|

400

|

|

Unemployed or inactive

|

5.5

|

11.3

|

11.0

|

15.3

|

257

|

|

Single mother

|

10.2

|

12.9

|

16.1

|

7.9

|

385

|

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

100.0

|

3,138

|

|

N of clusters

|

1675

|

750

|

804

|

420

|

3,649

|

|

% of clusters

|

45.9

|

20.6

|

22

|

11.5

|

100

|

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the 2018 Fertility Survey (EF 2018).