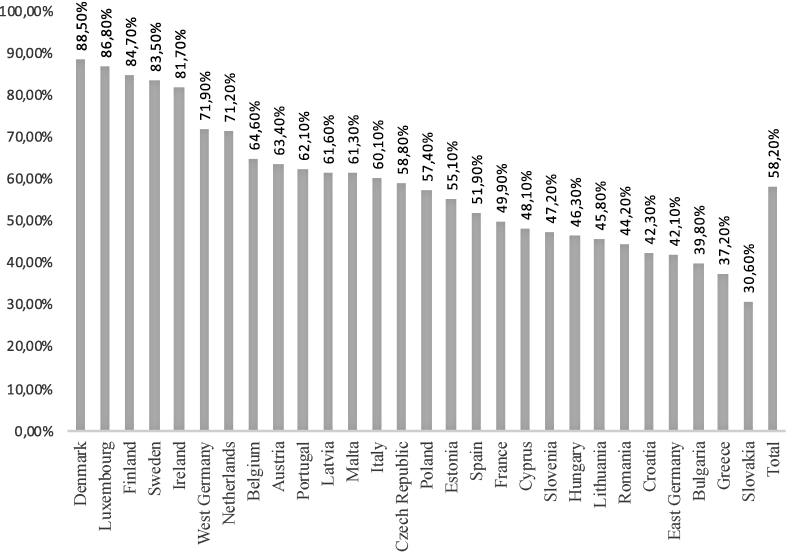

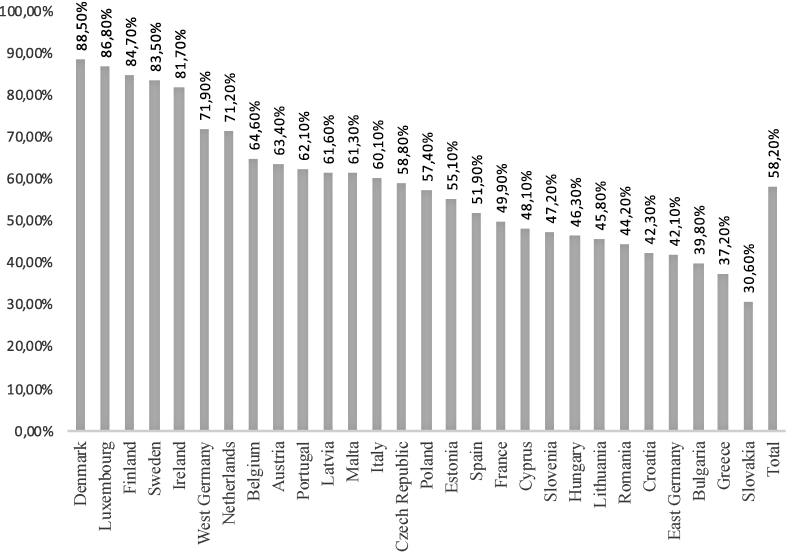

Graph 1. People who are SWD in the EU countries

Source: Author’s own creation.

doi:10.5477/cis/reis.192.47-66

Fake News and Factors of Discontent with Democracy. The Opinion of European Citizens

Fake news y factores de descontento con la democracia.

Opinión de los ciudadanos europeos

Antón Álvarez Sousa, María Andrade Suárez and Iria Caamaño Franco

|

Key words Institutional Quality

|

Abstract Over the 21st century, fake news (FN) and a lack of media freedom due to political and economic pressures have eroded citizen satisfaction with democracy (SWD). Discontent with democracy (DWD) has also been influenced by FN, media restrictions and social, economic and political factors. This study referred to data from the Eurobarometer. The technique of generalized structural equation modeling (GSEM) was used. The results indicate that variations in SWD among citizens may be explained by traditional factors (economic, social, and political) as well as by this novel element, fake news, which affects DWD both directly and indirectly through other variables such as political polarization. |

|

Palabras clave Calidad institucional

|

Resumen En el siglo xxi, las fake news (FN) y la falta de libertad de los medios de comunicación por presiones políticas y económicas erosionan la satisfacción de la ciudadanía con la democracia (satisfaction with democracy, SWD). El descontento con la democracia (disaffection with democracy, DWD) no solo está condicionado por las FN y por la falta de libertad de los medios, sino también por factores sociales, económicos y políticos. Se emplearon datos del Eurobarómetro y se aplicó la técnica de ecuaciones estructurales generalizadas (GSEM). Los resultados señalan la existencia de diferencias de SWD entre los ciudadanos que pueden explicarse por los factores clásicos (económicos, sociales y políticos), pero también por un nuevo factor que son las FN, las cuales influyen significativamente en el DWD de forma directa y a través de otras variables como la polarización política. |

Citation

Álvarez Sousa, Antón; Andrade Suárez, María; Caamaño Franco, Iria (2025). “Fake News and Factors of Discontent with Democracy. The Opinion of European Citizens”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 192: 47-66. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.192.47-66)

Antón Álvarez Sousa: Universidade da Coruña | antonio.alvarez@udc.es

María Andrade Suárez: Universidade da Coruña | maria.andrade@udc.es

Iria Caamaño Franco: Universidade da Coruña | Iria.caamano@udc.es

Introduction

The objective of this research is to analyze the importance of exposure to fake news (FN) on citizen satisfaction/dissatisfaction with democracy in European Union (EU) countries. The following questions are addressed: What factors influence the decline in satisfaction with democracy (SWD)? In addition to socioeconomic and political factors, does the lack of media freedom and exposure to FN influence this decline? Do individual and contextual factors also have an influence? Distinct organizations and scholars have suggested that a new societal crisis that is caused by FN may occur in the future and that it will most likely affect SWD (World Economic Forum, 2024; Foa et al., 2020; Mounk, 2018; Snyder, 2018; Runciman, 2019; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018).

Numerous analyses have been carried out on citizen dissatisfaction with democracy and a process of growing discontent (Foa et al., 2020). Some authors have referred to the death of democracies (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018). Classic analyses have examined citizen satisfaction and dissatisfaction with democracies based on distinct factors (Bobbío, 1986; Maravall, 1997; Molino and Montero, 1995; Montero et al., 1998). But a novel factor may be added to the classic ones: FN and the process of political polarization and institutional crisis. The World Economic Forum (WEF, 2024) has suggested that, over the coming years, the greatest global destabilization risk facing governments and companies is disinformation, an issue that is even more relevant than the climate crisis, armed conflicts and others.

To analyze the topic, writings such as that of Adam Przeworski (2019) on the crisis of democracy are especially relevant. He asked where this institutional wear and tear and polarization might lead. In response to the question “How do democracies die?” Levitsky and Ziblatt (2018), attempted to respond to this question of how do democracies die? They consider that our democracies are in danger, not because of a military coup or revolution, but because of the slow institutional weakening (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018). Discourse is produced by authoritarian leaders based on FN that results in a more polarized society, delegitimizing critics who denounce their strategies, engaging in control of communication and propaganda based on this FN to shape public opinion. They also discredit “unloyal” press that they are unable to control, in order to extend their attacks and their FN and persecute journalists.

But what is FN? Throughout history, the concept of truth has generated intense philosophical debates; no consensus exists as to the actual meaning of FN (Aïmeur, Amri and Bassard, 2023). For this study, we rely on the distinction proposed by McIntyre (2022) and Au, Ho and Chiu (2022). They differentiated between unintentional misinformation and intentional fake news. This definition allows us to more precisely analyze the impact of FN on discontent with democracy, without losing sight of the fact that, in the academic literature, there continue to be nuances and diverse approaches to the term. McIntyre differentiated between three forms of subverting the truth: error, willful ignorance and lying. “Error” refers to unintentionally saying things that are not true, without the intention of lying. “Willful ignorance” is when we do not really know if something is true, but we say it out of laziness, without checking if our information is correct. Finally, to “lie” is to “tell a falsehood with the intention of deceiving” but disguised as the truth (McIntyre, 2022: 37). For practical purposes, error and willful ignorance may be referred to as misinformation, while intentional lies disguised as the truth may be called FN. According to Au, Ho and Chiu:

From an academic perspective, disinformation can be understood as any misinformation, while fake news refers to news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false and misleading (2022: 1332).

Many authors agree that FN is “a key problem for contemporary democratic societies” (Sádaba and Salverría, 2023: 17). Therefore, distinct initiatives have been launched to combat them. Various publications on this issue have been drafted around the world and in the countries of the European Union (EU) and in Spain in particular. This is a symbol of the interest that it has sparked (Bak, Walter and Bechmann, 2023; Blanco-Herrero and Arcila-Calderón, 2019; Masip, Suau and Ruiz-Caballero, 2020; Figueruelo Burrieza and Martín Guardado, 2023; Cabrera Altieri, López García and Campos-Domínguez, 2024; Baptista and Gradim, 2022).

Factors influencing DWD

Not everyone has the same opinions about satisfaction or dissatisfaction with democracy. Individual responses vary depending on personal and contextual factors. SWD is related to socioeconomic and political factors, a lack of media freedom, and FN. The general idea is that individuals who are better positioned in the system (highly educated, well-off, with fewer financial difficulties, etc.) are more likely to display SWD than those who are less fortunate (Anderson and Gillory, 1997; Norris, 1999). In addition, exposure to an unfree media and FN are both influencing DWD (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018).

In addition to individual factors, it is also necessary to consider contextual factors. The spatial context:

May serve as a shortcut to information or heuristic content, since individuals living in the same context have common experiences which mold their political opinions and behaviors (Vasilopoulou and Talving, 2024: 1497).

These contextual factors may include habitat, the welfare state model, political polarization, institutional quality and political stability.

Montero et al. (1998) differentiated between legitimacy, discontent and disaffection. The term “discontent” refers to “the expression of frustration arising from the comparison of what one has and what one should have” (p. 18). Its components are “the effectiveness of the system and political satisfaction” (p. 18), such that individuals feel satisfied with democracy if it is effective at resolving their problems and, otherwise, there is a resulting deception and the corresponding discontent.

“Effectiveness” refers to a democracy’s ability to solve problems that are considered important by its citizens (Dahl, 1971; Morlino and Montero, 1995). This includes having a good job, a salary that allows you to avoid difficulties, having your voice heard by those who govern, living in a state that covers your basic needs, etc. When democracy does not satisfy these desires, individuals feel discontent as opposed to satisfaction.

Economic factors are very important for SWD (Lipset, 1959), therefore, their redistribution should be considered, specifically to ensure that no one has difficulties in making ends meet (Przeworski et al., 2000; Przeworski, 1997; Rose and Mishler, 1997; Pérez-Nievas et al., 2013). But it is also important to note that the evaluation of political attitudes “is also conditioned by political factors, and not only economic ones” (Pérez-Nievas et al., 2013: 193). Thus, “feelings of impotence and confusion with respect to politics” (Montero et al., 1998: 28) which may be reflected in a lack of discussion about political issues, feelings of helplessness or confusion about political ideologies, etc., are influencing society’s satisfaction/discontent with the democracy. The government is expected to resolve socioeconomic problems while simultaneously permitting political participation by listening to citizens (Christmann, 2018). Discussion on political issues is an indicator of democracy, beyond representative democracy (Contreras and Montecinos, 2019; Rabasa Gamboa, 2020; Bromo, Pacek and Radcliff, 2024). Although the concepts of participatory and deliberative democracy share the goal of extending beyond representative democracy, they respond to distinct processes. Participatory democracy refers mainly to direct citizen involvement in political decision-making (with participation through voting or mechanisms such as referendums, participatory budgets, etc.). In contrast, deliberative democracy emphasizes the quality of the deliberative process. In other words, it refers to a reasoned, rational, and respectful exchange between informed citizens with the goal of making fairer and more legitimate collective decisions.

Ideally, society would rely on the principles of deliberative democracy, where decisions are based on informed debate and collective reflection. Our analysis, which is conditioned by the limitations of the instrument used, does not accurately capture the deliberative dimension. Therefore, the question “Do you believe that your voice counts in your country?” should be considered, since it refers to a conception of participatory democracy relating to the perception of citizen influence in political processes, although it does not allow for an assessment of whether this influence is exercised through deliberative practices per se.

Factors such as the absence of a political ideology, discussion about relevant issues or the consideration that citizens are not being heard are leading to a weakening of democracy. David Van Reybrouck (2017) referred to this as “democratic fatigue syndrome”.

Currently, FN hiding large political and economic interests is another concerning factor that may directly and indirectly impact discontent with democracy (Herreras, 2021). Over recent years, various studies have reflected on a democratic crisis associated with FN. There is a general consensus that FN erodes the foundations of democracy (Farkas and Schou 2019; Monsees, 2023; Carson and Wright, 2022; Hurcombe and Meese, 2022; Habermas, 2023; Mounk, 2018; Snyder, 2018; Runciman, 2019; Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018).

Today’s society is one of “infocracy”, in which information determines social, economic and political processes (Han, 2022). With digitalization and the ease of issue of FN, a transformation of the public space has taken place, impacting politics and threatening democracy. Today, an apparent freedom exists, but information tends to be manipulated to produce destructive effects on opposition groups, giving rise to “undesirable consequences on democracy and social stability” (Au, Ho and Chiu, 2020: 1331). According to the postulates of the political economy of communication (Mosco, 2009), this information is controlled by those possessing political and economic power. This control represents a crisis for democracy (Bergés, 2010). The major communication platforms are in the hands of a few conglomerates that control the majority of the market (González Pazos, 2019).

A shift has taken place in the production and transmission of FN between classic and current media (McNair, 2018). Throughout history, political and economic powers have used propaganda and disinformation to influence individuals and public opinion. But with the arrival of the Internet and social media, this fake news is being manufactured and spread quickly and on a large scale. Han (2022) explains the difference between mediocracy and infocracy, and how information warfare is waged in infocracy. It is suggested that when television was the predominant medium, there was a media dramatization war, with television serving as a political stage. In infocracy, instead of media dramatization, information wars prevail. These are fought with great technical means. For example, the United States and Canada, where:

Voters are called by robots and are flooded with false news. Armies of trolls intervene in election campaigns by deliberately spreading fake news and conspiracy theories. Bots, automated fake social media accounts, impersonate real people and post, tweet, and disseminate false information, giving likes and sharing the same. They spread fake news, defamation and hateful comments (Han, 2022: 39).

It is no longer humans, but rather, huge machines, controlled by political and economic powers (García Calderón and Olmedo Neri, 2019) which transmit the FN and disinformation that may be damaging democracy, resulting in discontent amongst the population (Farkas and Schou, 2019; Herreras, 2021; World Economic Forum, 2024; Benítez, 2023; Knoll, Pitlik and Rode, 2023).

In contrast to those who view communication from an essentialist point of view, supporters of the political economy of communication consider that the media must be observed as part of society’s economic and political processes (Mosco, 2009: 111; Knoll, Pitlik and Rode, 2023). Economic power “affects the media, thus conditioning the production of public discourse... it allows some actors, and not others, to exercise power” (Bergés, 2010: 244). Regarding economic power, the power of the State is that of “producer, distributor, consumer and regulator of communication” (Mosco, 2009: 116).

With the advance of globalization and the expansion of the power of Western companies and countries, there has been an increased growth of media controlled by the great powers. This has led to the so-called “media imperialism” (Vaquerizo Domínguez, 2020). New actors have emerged in this imperialist control (Google, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, etc.). They control the global digital information flow, transmitting news that is of interest to those in power, many of which is FN. Certain alternative proposals are made by citizens and independent media in an attempt to transmit information that is beyond the control of the great powers. However, it is impossible to achieve this (Copley, 2018; Hachten, 1999; Nitrihual and Ulloa, 2022; McChensney, 2000; Mosco, 2009; Marwick and Lewis, 2024; Amorós García, 2018; Wardle and Derakhshan, 2017).

Different strategies are available to combat fake news and its effects. For example, Azzimonti and Fernandes (2023) analyzed the influence of bots on disinformation and social polarization. One strategy used to curb the effect of these bots is the use of counterbots. However, it has been concluded that these counterbots use may contribute to increased polarization. Therefore, the authors propose that the best strategy is to reduce the number of bots’ followers by “training people to identify fake news” (Azzimonti and Fernandes, 2023: 23). But this training is not a simple or fast job to carry out. Among other factors, it is associated with a high level of education of the population (Monsees, 2023; Stitzlein, 2023; European Commission, 2018; Hameleers and Meer, 2023). This type of educating may take years to complete. Education creates a more analytical and rational approach which is known as critical thinking. It allows us to question the underlying message and, thus, identify fake news (Lewandowsky, Ecker and Cook, 2017).

Contextual factors influencing DWD include habitat, the welfare state model of the country where one lives, political polarization, institutional quality, and political security.

People living in rural areas tend to feel abandoned by politicians (Sevilla, 2021; Collantes, 2020; Browne, 2001; Anderson and Valenzuela, 2008) and this is reflected in the DWD. Regarding the welfare state model, individuals living in more advanced welfare states have less dissatisfaction (Rhodes-Purdy, Navarre and Utych, 2023) and more SWD (Vargas Chanes and González Núñez, 2013). As Morlino and Montero (1995) suggested, when the state meets the basic needs of the population, individuals are more satisfied.

At a contextual level, political polarization is currently a highly concerning problem. When it is very high, political adversaries are not viewed as rivals, but rather as enemies to be defeated, thus weakening the rules of democracy. Where there is high polarization, there is an increased focus on blocking governments as opposed to attempting to cooperate between different parties to resolve problems. This makes citizens believe that democratic institutions do not represent them and, therefore, they display discontent with them, instead of satisfaction. This produces a social fragmentation leading to discontent with democratic institutions that are ultimately undermined, and that are dying. The weakness of our democratic norms is rooted in “an extreme partisan polarization. And if anything has become clear from the study of democratic failures over history, it is that extreme polarization can destroy democracy” (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018: 18). Democracies “erode slowly, in barely noticeable steps” (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018: 11). Runciman (2019) also suggests something similar in How Democracy Ends. Using the metaphor of a midlife crisis, the author states that, although democracy is not on the verge of death, it is in a certain state of exhaustion. In short, FN leads to polarization and a resulting DWD (Waisbord, 2020; McCoy, 2019; Osmundsen et al., 2021; Au, Ho and Chiu, 2022).

FN also weaken institutional quality (Bennett and Livingston, 2018) increasing discontent with democracy (Norris, 2011). People living in countries with high institutional quality tend to be more satisfied with democracy than those in countries of low institutional quality. If we want to increase SWD, we must improve the quality of institutions (Diamond, 1999). Otherwise, the judicial system, parliament or the media will lose the trust of the population.

Regarding the path leading to an unfree media, FN and polarization, Au, Ho and Chiu (2022) suggest that several sequential stages exist: “The mechanism begins with malicious intentions” (Au, Ho and Chiu, 2022: 1345) caused by political and economic incentives. These malicious intentions are followed by disinformation and online and even traditional media FN. This causes vigorous debates and, simultaneously, the polarization of society, the loss of institutional quality, and political stability. All of this makes citizens dissatisfied with democracy. In our analysis, we will discuss the political and economic intentions that exert pressure by curtailing media freedom, their influence on FN, and FN’s influence on polarization, the loss of institutional quality, political stability, and, finally, DWD.

Although not as analytically detailed, this sequencing was also indicated by Amorós García (2018). He believes that fake news divides society, thus the title of Chapter 20 of his book: Fake news divides: you’re one of mine, right? Many rulers use FN and “seek to focus the discourse on a clear division between those who think like them and those who are against them” (Amorós García, 2018: 93). In this environment of polarization, instead of seeking dialogue with those who think differently, as should occur in a democratic environment, people attempt to lock themselves in the “echo chamber”. This FN may go viral within their own circle, not relating to those who think differently and amplifying the news “by going viral within a closed circle where different views are censored” (Amorós García, 2018: 93).

In short, DWD is expected to be conditioned by classic individual socioeconomic and political factors. Currently, these factors are being compounded by FN, which is conditioned by political and economic powers.

Contextual factors are also important, such as the welfare state model and, consequently, the provision of necessary services to the population, the political polarization of the country in which they live, and the loss of institutional quality and security. These variables are, in turn, conditioned by FN, which exerts a direct influence on DWD and an indirect influence through polarization, the loss of institutional quality, and political stability.

Methodology and source

of data

For the dependent variable DWD and for the individual independent variables, the data have been taken from Eurobarometer 98.2 (2023). The reference question for the dependent variable is: “Generally speaking, would you say that you are very satisfied, rather satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with the functioning of democracy in your country?”. For bivariate and multivariate analyses, this variable was recoded in two categories: satisfied (very satisfied and rather satisfied) and dissatisfied (not very satisfied, not at all satisfied and the Don’t know/No comment).

The following questions are considered to be “individual independent variables” related to FN, socioeconomic and political factors:

The following independent contextual variables have been taken into account: size of the community where they live, the welfare state model of the country where they live, political polarization, institutional quality and political stability.

The “political polarization” variable (Polarizacionpol) was based on data from the V-dem 2023, specifically, the question “Is the society in which you live polarized into antagonistic political camps?”. Possible responses range from “0, not at all polarized” to “4, very polarized”.

The “institutional quality” variable (Calidadinst) corresponds to the WGIs of the European Quality of Government Index. For this variable, the higher the score, the higher the institutional quality.

The “political stability” variable (Estabilpolit) comes from the World Bank. It measures perceptions regarding the likelihood of political instability and/or politically motivated violence, including terrorism. The percentile value was taken, with 0 being the lowest range of political stability and 100 being the highest range.

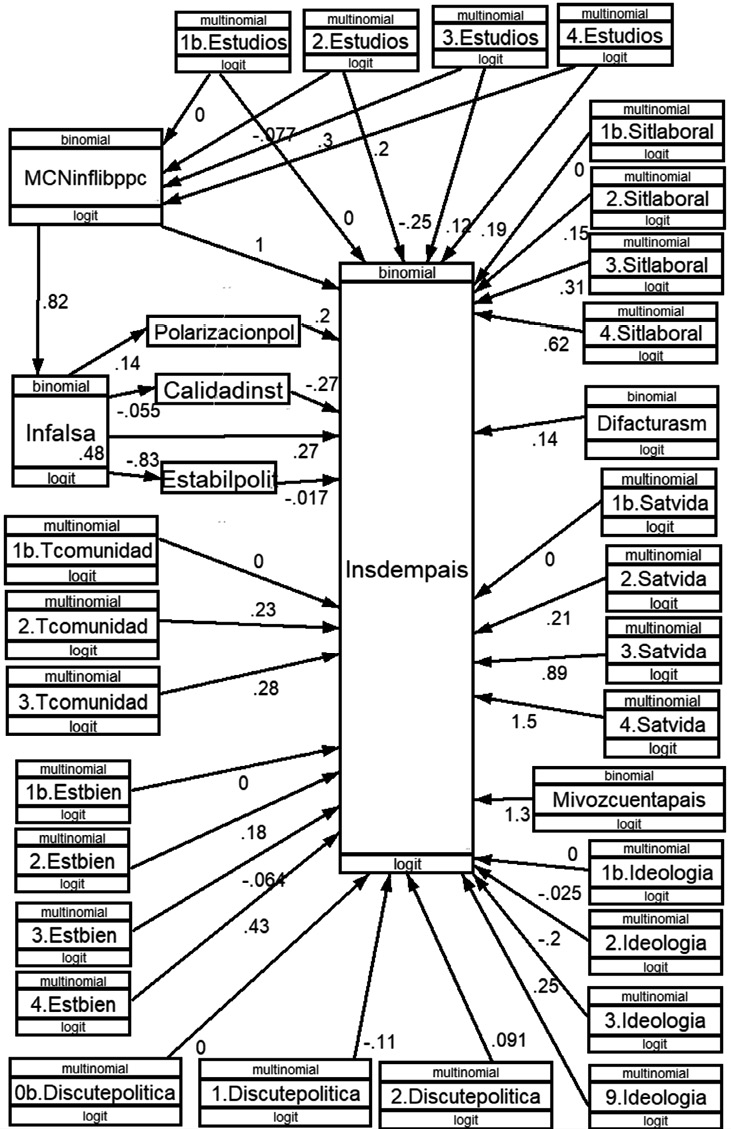

For the bivariate analysis, contingency tables were created (percentages and chi-square values). For the multilevel analysis, the Generalized Structural Equation Model (GSEM) was used as well as Stata software. The coefficients were transformed into Odds Ratio (OR), analyzing the significance of z (P>z) taking into account the variables that were statistically significant (value 0.05 or lower) in the final model.

In the GSEM model, all variables that were significant at the bivariate level were initially included. Those that were no longer significant in all categories were then eliminated. A third step analyzed the appropriateness of continuing or not maintaining variables for which only some categories were significantly associated. For this, fit tests were performed using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian (or Schwarz) information criterion (BIC)2. Thus, for some variables that were significant in certain categories but not in others, the AIC and BIC were determined, to see if the model fit better with or without them. Finally, the model having the best fit was selected.

Results

“SWD in the country” only attained an average of 58.2 % for the EU citizens (Chart 1) but major differences were found between countries. Between 88.5 % and 81.7 % in Denmark, Luxembourg, Finland, Sweden and Ireland. Between 71.9 % and 71.2 % in West Germany and the Netherlands. Between 64.6 % and 60.10 % in Belgium, Austria, Portugal, Latvia, Malta and Italy. Between 58.8 % and 51.9 % in the Czech Republic, Poland, Estonia and Spain. France, Cyprus, Slovenia, Hungary, Lithuania, Romania, Croatia, and East Germany are in the 40 % percentile range. Bulgaria, Greece, and Slovakia are in the 39.8 % to 30.6 % range.

SWD in the country. Bivariate analysis

The consideration of individuals who “are exposed to FN” is influencing DWD (Table 1), with discontent rising from 35.4 % for those who disagree with being exposed to FN to 44.7 % for those who consider that they are exposed to FN. Therefore, if individuals consider that they are exposed to FN, it is more likely that they will display DWD.

Another factor influencing DWD is the consideration of whether the “mass media offers information that is free (or not free) of political and commercial pressure”. This influence is very high, with the DWD increasing from 26.6 % for those who consider that the media offer information free of such pressures, to 56.7 % for those who believe that the media are not free, and that pressure is exerted by political and economic powers on the information that is broadcast.

The ability to “identify FN” reduces dissatisfaction with democracy. Amongst those who believe they can identify FN, 39.4 % express dissatisfaction. However, amongst those who believe they are unable to identify FN, 45.5 % express dissatisfaction. However, we must take into account other variables that may influence the ability to identify fake news. Based on the survey results, we can affirm that an individual’s educational level helps them to identify fake news (Table 2). As education level decreases, so does the belief that they are able to identify fake news, decreasing from 69.7 % in those having a high education level to 64.5 % in those currently studying, 61.3 % in those with an average education level, and 45.2 % in those with a low or non-existent education level. This suggests that we should pay close attention to the results of the multivariate analysis to determine whether the ability to identify fake news continues to have an impact after including educational level or if its influence is no longer significant. Educational level also influences opinions on media freedom: the higher the educational level, the more likely to believe that the media is free.

With the current change in communication caused by FN, democracy is at risk of crumbling. One of the strategies undertaken to solve this is public debate (Montero et al., 1998; Habermas, 2023). As a result, individuals who “debate politics” are less likely to demonstrate discontent with democracy than those who do not debate: 52.0 % of those who never debate, 41.3 % of those who sometimes debate, and 36.9 % of those who frequently debate declared to be DWD.

Politicians taking into account the voices of citizens serves as an indicator of participatory democracy. This is reflected in the question “Does my voice count in my country?”. Discontent ranges from 24.3 % (in my country, my voice counts) to 66.8 % (my voice doesn’t count in my country). Therefore, it is very important to take people’s opinions into account if we want them to display SWD.

Satisfaction or dissatisfaction with democracy is also influenced by one’s level of educational, occupational, or economic capital. Those having a high educational level display low levels of dissatisfaction with democracy (accounting for 34.2 %), as compared to those with an average education level (46.7 %) and those with a low or non-existent education level (50.7 %).

The individual’s “work situation” also has a significant influence. As we go from a very good employment situation to a bad one, dissatisfaction increases. Of those having a very good employment situation, DWD percentages were 27.7 %, those with a good situation, 37.7 %, a rather bad situation, 56.0 %, and a very bad one, 68.0 %. The individual’s economic situation is also influential: those who do not have difficulties paying their bills at the end of the month accounted for 35 % of the total DWD percentages, as opposed to 53.8 % for those having difficulties.

As for “ideology”, while right-wing individuals are slightly more dissatisfied than those on the left, the greatest discontent is found amongst those who do not know which ideology they identify with, or those who refuse to identify with any of them.

Regarding contextual variables, in the case of the “community size” variable, individuals living in cities accounted for lower levels of DWD (38 %) as compared to those living in towns (43.2 %) and rural areas (43.3 %).

The welfare state model also has a very important influence on DWD in the country, accounting for 14.8 % in the Nordic model, 36.9 % in the Continental + Ireland model, 44.7 % in the Mediterranean model and 50.9 % in the Eastern European countries that belonged to the former Soviet Union.

Political polarization, institutional quality, and political stability also have a significant influence: greater political polarization results in higher DWD. When institutional quality increases, DWD decreases and when political stability increases, DWD also decreases.

Multivariate explanation

of DWD

An initial GSEM analysis was performed with all of the variables that were significant at the bivariate level. Upon introducing these variables into the model, the ease of identifying fake news was no longer significant. This led us to perform a second GSEM analysis without this variable. The result is a model in which all variables are significant and, furthermore, the influence of almost all categories is also significant, as seen in the P>z in Table 2, with almost all values being lower than 0.05. Debating politics was the one that was associated with the lowest strength at the multivariate level (not all categories were significantly associated). Therefore, it was removed from the model and a test was performed with a third GSEM model without this variable. But when analyzing the AIC and BIC of both models, it was found that if this variable was not taken into account, the fit is weaker. Therefore, we decided to also consider the “debating politics” variable into account in the final model (Graph 2 and Table 3).

When people believe that they are exposed to FN, their probability of being DWD increases. For every hundred people displaying discontent who do not believe that they are being exposed to FN, there are 131 who display DWD and do believe that they are exposed to FN.

When people believe that the media are not free from political and commercial pressures, their probability of displaying DWD in their countries increases from 100 individuals among those who consider that the media offer free information, to 273 among those who consider that the media do not offer free information.

Economic, labor, and training factors also have a very important influence on DWD, which is associated with people having a bad “work situation, difficulties paying their bills” at the end of the month and few “studies”. For every hundred people displaying DWD who have high studies, there are 113 having average studies and 121 with few or no studies. Regarding the work situation, for every hundred people who display discontent and have a very good work situation, there are 116 with a good situation, 136 with a relatively bad situation and 185 with a very bad situation. As for those with difficulties paying their bills at the end of the month, for every hundred people displaying DWD who do not have difficulties, there are 115 who do have difficulties.

The “life satisfaction” variable has a high weight. When people are satisfied with their life, they are less DWD. For every hundred people who display DWD who are very satisfied with their lives, there are 123 who are somewhat satisfied, 244 who are not very satisfied and 440 who are not at all satisfied.

Variables related to “ideology” and the belief that “they are heard” in democracy (“my voice counts in this country”) also have a significant influence. When citizens perceive that their voice does not count in their country, they display great dissatisfaction with democracy: for every hundred who believe they are heard and are dissatisfied, there are 375 DWD who believe they are not heard. People on the right are less DWD than those on the left, although the greatest dissatisfaction is found among those who refuse to identify with an ideology or who do not respond.

Contextual variables have a significant influence. As community size decreases, DWD increases. For every hundred people living in cities who express discontent, there are 126 who live in towns and 132 who reside in rural areas.

As for the influence of the welfare state, for every hundred people who are DWD and live in Nordic countries, there are 120 from the continental model and Ireland, and 154 from Eastern Europe.

Political polarization also has a significant influence, with DWD increasing as political polarization increases. Institutional quality has an inverse influence, such that as institutional quality increases, DWD decreases. Political stability has a similar influence: as political stability increases, DWD decreases.

But in our analysis with GSEM, in addition to the direct influence of the variables on the DWD, we also analyzed a number of other effects. FN directly influences DWD, but it also has an indirect influence on it, since it simultaneously affects other variables that influence DWD, such as political polarization, institutional quality, and political stability.

Conclusions

The “probability of displaying DWD” is influenced by a variety of factors, both individual and contextual. Of the individual factors, various aspects are influential: socioeconomic, employment, academic, or political. The influence of FN, a specific factor that we sought to analyze in this research, is also fundamental, as is the lack of freedom of the media. Likewise, contextual factors related to the habitat, the welfare state model of the country where they live and other factors such as political polarization, institutional quality and political stability have a significant influence.

For the socioeconomic, employment and education variables, the winners and losers hypothesis from the system created by Anderson and Gillery (1997) has been verified. In other words, the more the individuals are considered “winners”, the higher the SWD and the more they are considered “losers” (lower education level, worse employment situation, more difficulties in paying bills at the end of the month, lower satisfaction with life), the higher the DWD.

Political participation also plays a relevant role. When people lack a defined ideology, refrain from political debate, and believe that their voice is not heard in their country’s decision-making, they are more likely to display DWD. When citizens’ voices are lacking, politicians may prioritize their own interests or those of economic elites, without considering those of society. In the face of a direct government of elected leaders, when citizens feel that their voice is heard, they are more likely to display SWD. Some authors have suggested that there is a lack of citizen interest in a representative democracy (Rabasa Gamboa, 2020: 353). David van Reybrouck (2017) coined this “democratic fatigue syndrome”.

The thesis of Vasilopoulou and Talving (2024), which emphasizes the need to consider contextual effects, has also been verified.

Individuals living in rural areas are more dissatisfied and feel less heard with respect to democratic decision-making. Development is focusing on urban areas to the detriment of rural areas, which tend to lack services and appeal to stay there (Seville, 2021). Living in a country with a high welfare state also significantly influences SWD.

The image of lack of freedom in the media, which is subject to political and financial powers, undermines satisfaction with democracy in two ways: directly and through the perception that one is exposed to FN. The thesis of the political economy of communication is fulfilled (Mosco, 2009; Knoll, Pitlik and Rode, 2023).

Exposure to FN directly affects DWD. And it also indirectly affects it through other variables. FN leads to political polarization, a loss of institutional quality, and political stability (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2018). This is endangering democracy, which may slowly die.

With the influence of certain variables on others until reaching the DWD, the theory of Au, Ho and Chiu (2022) and Amorós García (2018) on the process of influence of FN on DWD is fulfilled. It begins with political and economic interests. FN is produced and directly influences DWD. However, in turn, FN influences political polarization, institutional quality and political stability, all of which condition DWD. Thus, there is a direct influence of FN on DWD, as well as an indirect one.

To further expand the analysis, over the coming years, the Eurobarometer should include more specific questions on media literacy, participatory democracy, and the independent nature of disinformation caused by error or ignorance. We will look into ways to implement this suggestion.

Bibliography

Aïmeur, Esma; Amri, Sabrine and Brassard, Gilles (2023). “Fake News, Disinformation and Misinformation in Social Media: A Review”. Social Networks Analysis and Mining, 13(30): 1-36. doi: 10.1007/s13278-023-01028-5

Amorós García, Marc (2018). Fake News. La verdad de las noticias falsas. Barcelona: Plataforma Editorial.

Anderson, Christopher J. and Guillory, Christine A. (1997). “Political Institutions and Satisfaction with Democracy: A Cross-national Analysis of Consensus and Majoritarian Systems”. American Political Science Review, 91(1): 66-81. doi: 10.2307/2952259

Anderson, Kym and Valenzuela, Ernesto (2008). Estimates of Global Distortions to Agricultural Incentives, 1955 to 2007. Washington: World Bank.

Au, Cheuk H.; Ho, Kevin K.W. and Chiu, Dickson K.W. (2022). “The Role of Online Misinformation and Fake News in Ideological Polarization: Barriers, Catalysts, and Implications”. Information Systems Frontiers, 24: 1331-1354. doi: 10.1007/s10796-021-10133-9

Azzimonti, Marina and Fernandes, Marcos (2023). “Social Media Networks, Fake News, and Polarization”. European Journal of Political Economy, 76, 102256: 1-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2022.102256

Bak, Petra D. P.; Walter, Jessica G. and Bechmann, Anja (2023). “Digital False Information at Scale in the European Union: Current State of Research in Various Disciplines, and Future Directions”. New Media and Society, 25(10): 2800-2819. doi: 10.1177/14614448221122146

Baptista, Joao Pedro and Gradim, Anabela (2022). “A Working Definition of Fake News”. Encyclopedia, 2(1): 632-645. doi: 10.3390/encyclopedia2010043

Benítez, Ricardo (2023). “Michael Sandel”. Telos, 122: 26-34.

Bennett, Lance and Livingston, Steven (2018). “The Disinformation Order: Disruptive Communication and the Decline of Democratic Institutions”. European Journal of Communication, 33(2): 122-139.

Bergés Saura, Laura (2010). “Poder político, económico y comunicativo en la sociedad neoliberal”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 65: 244-254.

Blanco-Herrero, David and Arcila-Calderon, Carlos (2019). “Deontology and Fake News: A Study of the Perceptions of Spanish Journalists”. Profesional de la información, 28(3): 1-13.

Bobbio, Norberto (1986). El futuro de la democracia. México: Fondo de la Cultura Económica.

Bromo, Francesco; Pacek, Alexander C. and Radcliff, Benjamin (2024). “Varieties of Democracy and Life Satisfaction: Is There a Connection?”. Social Science Quarterly, 105(4): 1152-1163.

Browne, William P. (2001). The Failure of National Rural Policy: Institutions and Interests. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Cabrera Altieri, Daniel H.; López García, Guillermo and Campos-Domínguez, Eva (2024). “Desinformación y mediatización. Desafíos de la investigación en comunicación política”. Zer: Revista de estudios de comunicación, 29(56): 13-16. doi: 10.1387/zer.26415

Carson, Andrea and Wright, Scott (2022). “Fake News and Democracy: Definitions, Impact and Response”. Australian Journal of Political Science, 57(3): 221-230. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2022.2080014

Christmann, Pablo (2018). “Economic Performance, quality of Democracy and Satisfaction with Democracy”. Electoral Studies, 53: 79-89. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.04.010

Collantes, Fernando (2020). “Tarde, mal y... ¿quizá nunca? La democracia española ante la cuestión rural”. Panorama social, 31: 15-32.

Contreras, Patricio and Montecinos, Egon (2019). “Democracia y participación ciudadana: Tipología y mecanismos para la implementación”. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 25(2): 178-191.

Copley, Fernanda (2018). “El camino de las TIC: del Nuevo Orden Mundial al imperio del Big Data”. Alcance, 7(15): 45-66.

Dahl, Robert A. (1971). Polyarchy. Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Diamond, Larry (1999). Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

European Commission (2018). Action Plan Against Disinformation. December 5. Brussels. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/b654235c-f5f1-452d-8a8c-367e603af841_en?filename=eu-communication-disinformation-euco-05122018_en.pdf, access July 1, 2024.

Farkas, Johan and Schou, Jannick (2019). Post-Truth, Fake News and Democracy. New York: Routledge.

Figueruelo Burrieza, Ángela and Martín Guardado, Sergio (2023). Desinformación, odio y polarización (I). Navarra: Thomson Reuters Aranzadi.

Foa, Roberto S.; Klassen, Anna; Slade, Michael; Rand, Alexander and Collins, Rachel (2020). The Global Satisfaction with Democracy Report 2020. Bennett Institute for Public Policy: University of Cambridge.

García Calderón, Carola and Olmedo Neri, Raúl A. (2019). “El nuevo opio del pueblo: apuntes desde la Economía Política de la Comunicación para (des)entender la esfera digital”. Iberoamérica Social: Revista-red de estudios sociales, 7(12): 84-96.

González Pazos, Jesús (2019). Medios de comunicación. ¿Al servicio de quién? Barcelona: Icaria.

Habermas, Jürgen (2023). A New Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere and Deliberative Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hachten, William A. and Scotton, James F. (2012). The World News Prism: Changing Media, Clashing Ideologies. Iowa: Iowa State University Press.

Hameleers, Michael and Meer, Toni van der (2023). “Striking the Balance Between Fake and Real: Under what Conditions can Media Literacy Messages that Warn About Misinformation Maintain Trust in Accurate Information?”. Behaviour and Information Technology: 1-13. doi: 10.1080/0144929X.2023.2267700

Han, Byung-Chul (2022). Infocracia: La digitalización y la crisis de la democracia. Buenos Aires: Taurus.

Herreras, Emilio (2021). Lo que la posverdad esconde: medios de comunicación y crisis de la democracia. Barcelona: MRA Ediciones.

Hurcombe, Eliza and Meese, James (2022). “Australia’s DIGI Code: What Can We Learn from the EU Experience?”. Australian Journal of Political Science, 57(3): 297-307. doi: 10.1080/10361146.2022.2080013

Knoll, Benjamin; Pitlik, Hans and Rode, Martin (2023). “TV Consumption Patterns and the Impact of Media Freedom on Political Trust and Satisfaction with the Government”. Social Indicators Research, 169(1): 323-340. doi: 10.1007/s11205-023-03073-3

Levitsky, Steven and Ziblatt, Daniel (2018). Cómo mueren las democracias. Barcelona: Ariel.

Lewandowsky, Sthepan; Ecker, Ullrich K. H. and Cook, John (2017). “Beyond Misinformation: Understanding and Coping with the «Post-Truth» Era”. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4): 353-369. doi: 10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Lipset, Seymour (1959). Algunos requisitos sociales de la democracia: desarrollo económico y legitimidad política. In: A. Batlle (ed.). Diez textos básicos de ciencia política. Madrid: Editorial Ariel.

Maravall, José M. (1997). Regimes, Politics and Markets. Democratization and Economic Change in Southern and Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marwick, Alice and Lewis, Rebecca (2024). Media Manipulation and Dis-information Online. Data and Society. Available at: https://datasociety.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/Manipulacao-da-midia-e-desinformacao-online.pdf, access February 14, 2025.

Masip, Pere; Suau, Jaume and Ruiz-Caballero, Carlos (2020). “Percepciones sobre medios de comunicación y desinformacaión: ideología y polarización en el sistema mediático español”. Profesional de la Información, 29(5): 1-13. doi: 10.3145/epi.2020.sep.27

McChesney, Robert W. (2000). “The Political Economy of Communication and the Future of the Field”. Media, Culture and Society, 22(1): 109-116.

McCoy, Jennifer (2019). “La polarización perjudica a la democracia y la sociedad”. Por la paz, 36: 1-7. Available at: https://www.icip.cat/perlapau/es/articulo/la-polarizacion-perjudica-a-la-democracia-y-la-sociedad/, access February 15, 2025.

McIntyre, Lee (2022). Posverdad. Madrid: Cátedra.

McNair, Brian (2017). Fake News: Falsehood, Fabrication and Fantasy in Journalism. London: Routledge.

Monsees, Lise (2023). “Information Disorder, Fake News and the Future of Democracy”. Globalizations, 20 (1): 153-168. doi: 10.1080/14747731.2022.2072894

Montero, José R.; Gunther, Richard; Torcal, Mariano and Menezo, José C. (1998). “Actitudes hacia la democracia en España: legitimidad, descontento y desafección”. REIS, 83: 9-49.

Morlino, Leonardo and Montero, José R. (1995). Legitimacy and Democracy in Southern Europe. In: R. Gunther; P. N. Diamandouros and H.-J. Puhle (eds.). The Politics of Democratic Consolidation. Southern Europe in Comparative Perspective. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mosco, Vicent (2009). La Economía Política de la Comunicación. Reformulación y Renovación. Barcelona: Bosch.

Mounk, Yascha (2018). El pueblo contra la democracia: por qué nuestra libertad está en peligro y cómo salvarla. Barcelona: Paidós.

Nitrihual Valdebenito, Luis and Ulloa Galindo, Claudio (2022). “Economía Política de la Comunicación y estudio de las hegemonías discursivas: Fundamentos para comprender lo social”. Revista Internacional de Comunicación y Desarrollo (RICD), 4(16):1-15. doi: 10.15304/ricd.4.16.8421

Norris, Pippa (1999). Institutional Explanations for Political Support. In: P. Norris (ed.). Critical Citizens. Global Support for Democratic Governance. New York: Oxford University Press.

Norris, Pippa (2011). Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Osmundsen, Mathias; Bor, Alexander; Vahlstrup, Peter B.; Bechmann, Anja and Petersen, Michael B. (2021). “Partisan Polarization is the Primary Psychological Motivation Behind Political Fake News Sharing on Twitter”. American Political Science Review, 115(3): 999-1015.

Pérez-Nievas, Santiago; García Albacete, Gema; Martín, Iván; Montero, José R.; Sanz, Amparo; Lorente, Jesús and Mata, Tomás (2013). “Los efectos de la crisis económica en la democracia española: legitimidad, insatisfacción y desafección”. Proyecto de Investigación del Departamento de Ciencia Política y Relaciones Internacionales, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Available at: https://portalcientifico.uam.es/es/ipublic/item/2823413, access February 10, 2025.

Przeworski, Adam (1997). “Una mejor democracia, una mejor economía”. Claves de Razón Práctica, 70: 2-9

Przeworski, Adam (2019). Crisis of Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Przeworski, Adam; Alvarez, Michael E.; Cheibub, José A. and Limongi, Fernando (2000). Democracy and Development Political Institutions and Well-being in the World 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rabasa Gamboa, Emilio (2020). “La democracia participativa, respuesta a la crisis de la democracia representativa”. Cuestiones Constitucionales, 43: 351-376.

Rhodes-Purdy, Matthew; Navarre, Raúl and Utych, Stephen (2023). The Age of Discontent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, Richard and Mishler, William (1997). “Trust, Distrust and Skepticism: Popular Evaluations of Civil and Political Institutions in Post-Communist Societies”. The Journal of Politics, 59(2): 418-451. doi: 10.2307/2998170

Runciman, David (2019). Así termina la democracia. Barcelona: Paidós.

Sádaba, Charo and Salaverría, Ramón (2023). “Tackling Disinformation with Media Literacy: Analysis of Trends in the European Union”. Revista Latina de Comunicación Social, 81: 17-32. doi: 10.4185/RLCS-2023-1552

Sevilla, Jordi (2021). The Divide Between the Rural and the Urban World. TheSocialObservatory. Available at: https://elobservatoriosocial.fundacionlacaixa.org/en/-/the-divide-between-the-rural-and-the-urban-world, access Februay 20, 2025.

Snyder, Timothy (2018). El camino hacia la no libertad. Barcelona: Galaxia Gutemberg.

Stitzlein, Sarah (2023). “Teaching Honesty and Improving Democracy in the Post-Truth Era”. Educational Theory, 73(1): 51-73. doi: 10.1111/edth.12565

Van Reybrouck, David (2017). Contra las elecciones: Cómo salvar la democracia. Madrid: Taurus.

Vaquerizo Domínguez, Enrique (2020). “Medios de comunicación y flujos culturales internacionales: la vigencia actual del informe McBride”. Revista de Comunicación de la SEECI, 51: 43-62. doi: 10.15198/seeci.2020.51.43-62

Vargas Chanes, Delfino and González Núñez, Juan C. (2013). “Los determinantes de la satisfacción con la democracia, desde el enfoque de un modelo multinivel”. EconoQuantum, 10(2): 55-75.

Vasilopoulou, Sofia and Talving, Liisa (2024). “Euroscepticism as a Syndrome of Stagnation? Regional Inequality and Trust in the EU”. Journal of European Public Policy, 31(6): 1494-1515. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2023.2247961

Waisbord, Silvio (2020). “¿Es válido atribuir la polarización política a la comunicación digital? Sobre burbujas, plataformas y polarización afectiva”. Revista SAAP, 14 (2): 249-279.

Wardle, Claire and Derakhshan, Hossein (2017). Information disorder: Toward an Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policymaking. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

World Economic Forum (2024). The Global Risks Report 2024. Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

1 To avoid constantly repeating “You often find news or information that you believe distorts reality and even is false”, we will simply say fake news or FN, with the understanding that we are referring to those that are false or that distort reality.

2 When working with nominal or ordinal variables, we must use the GSEM model instead of the SEM model. The AIC and BIC are the fit criteria indicated for GSEM models, which are not used to judge fits in absolute terms, but rather, to compare the best-fitting model, which is the one having the smallest values.

Graph 1. People who are SWD in the EU countries

Source: Author’s own creation.

Table 1. Satisfaction-dissatisfaction with democracy according to exposure to FN and other socioeconomic and political variables

|

Satisfied |

Dissatisfied |

||

|

Mass media offer information that is free of political and commercial pressures (MCNinflibppc) |

Yes |

73.4 |

26.6 |

|

No |

43.3 |

56.7 |

|

|

You often find news or information that you believe distorts reality and is even fake (Infalsa) |

Disagree or others |

64.6 |

35.4 |

|

Agree |

55.3 |

44.7 |

|

|

It is easy for you to identify news or information that you believe |

Disagree or others |

54.5 |

45.5 |

|

Agree |

60.6 |

39.4 |

|

|

Debates politics (Discutepolitica) |

Frequently |

63.1 |

36.9 |

|

Sometimes |

58.7 |

41.3 |

|

|

Never |

48.0 |

52.0 |

|

|

Difficulties paying bills at the end of the month (Difacturasm) |

No |

65.0 |

35.0 |

|

Yes |

46.2 |

53.8 |

|

|

Education level (Estudios) |

High |

65.8 |

34.2 |

|

Studying |

68.0 |

32.0 |

|

|

Average |

53.3 |

46.7 |

|

|

Low or no studies |

49.3 |

50.7 |

|

|

Personal work situation (Sitlaboral) |

Very good |

72.3 |

27.7 |

|

Good |

62.3 |

37.7 |

|

|

Relatively bad |

44.0 |

56.0 |

|

|

Very bad |

32.0 |

68.0 |

|

|

Satisfaction with lifestyle (Satvida) |

Very satisfied |

71.2 |

28.8 |

|

Somewhat satisfied |

61.9 |

38.1 |

|

|

Not very satisfied |

33.7 |

66.3 |

|

|

Not at all satisfied |

17.4 |

82.6 |

|

|

Ideological position |

Left |

60.6 |

39.4 |

|

Center |

60.7 |

39.3 |

|

|

Right |

58.7 |

41.3 |

|

|

Reject |

41.0 |

59.0 |

|

|

My voice is heard in my country |

Yes |

75.7 |

24.3 |

|

No |

33.2 |

66.8 |

|

|

Community size (Tcomunidad) |

Cities |

62.0 |

38.0 |

|

Towns |

56.8 |

43.2 |

|

|

Rural |

56.7 |

43.3 |

|

|

Welfare State Model (Estbien) |

Nordic |

85.2 |

14.8 |

|

Continental + Ireland |

63.1 |

36.9 |

|

|

Mediterranean |

55.3 |

44.7 |

|

|

Eastern Europe |

49.1 |

50.9 |

|

|

Political polarization (Polarizacionpol) |

2.0 |

2.3 |

|

|

Institutional quality (Calidadinst) |

2.7 |

2.6 |

|

|

Political stability (Estabilpolit) |

68.8 |

65.8 |

|

|

Total |

58.2 |

41.8 |

|

Source: Author’s own creation.

Table 2. Influence of educational level on the identification of fake news and opinions on media freedom

|

It is easy for you to identify news or information that you believe distorts reality or is even fake |

Total |

National media provide information that is free from political and commercial pressures |

Total |

||||

|

Disagree or others |

Agree |

No |

Yes |

||||

|

Education level |

High |

30.3 ٪ |

69.7 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

29.6 ٪ |

70.4 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

|

Studying |

35.5 ٪ |

64.5 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

29.0 ٪ |

71.0 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

|

|

Average |

38.7 ٪ |

61.3 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

41.0 ٪ |

59.0 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

|

|

Low |

54.8 ٪ |

45.2 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

39.6 ٪ |

60.4 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

|

|

Total |

37.1 ٪ |

62.9 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

35.5 ٪ |

64.5 ٪ |

100.0 ٪ |

|

Source: Author’s own creation.

Graph 2. GSEM diagram with coefficients

Source: Developed by the authors.

Table 3. DWD in the country where you live according to the GSEM model

|

Coef. |

OR |

P>z |

[95 % Conf. Interval] |

||||

|

Insdempais <- |

|||||||

|

INDIVIDUAL VARIABLES |

|||||||

|

MCNinflibppc (The mass media offers information that is free from political and commercial pressure) |

Yes |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

No |

1.004 |

2.73 |

0.000 |

0.934 |

1.074 |

||

|

Infalsa (You often find news |

Disagree |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Agree |

0.274 |

1.31 |

0.000 |

0.195 |

0.352 |

||

|

Education (Education level) |

High |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Studying |

-0.253 |

0.78 |

0.001 |

-0.406 |

-0.100 |

||

|

Average |

0.120 |

1.13 |

0.003 |

0.041 |

0.198 |

||

|

Low or without studies |

0.191 |

1.21 |

0.005 |

0.058 |

0.325 |

||

|

Discutepolítica (Debate politics) |

Frequently |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Sometimes |

-0.106 |

0.90 |

0.007 |

-0.184 |

-0.029 |

||

|

Never |

0.091 |

1.10 |

0.130 |

-0.027 |

0.209 |

||

|

Sitlaboral (Personal work situation) |

Very good |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Good |

0.149 |

1.16 |

0.004 |

0.049 |

0.249 |

||

|

Somewhat bad |

0.307 |

1.36 |

0.000 |

0.181 |

0.433 |

||

|

Very bad |

0.616 |

1.85 |

0.000 |

0.440 |

0.792 |

||

|

Difacturasm (Difficulties in paying |

No |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Yes |

0.142 |

1.15 |

0.000 |

0.065 |

0.220 |

||

|

Satvida (Satisfaction with lifestyle) |

Very satisfied |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Somewhat satisfied |

0.207 |

1.23 |

0.000 |

0.111 |

0.303 |

||

|

Not very satisfied |

0.890 |

2.44 |

0.000 |

0.758 |

1.022 |

||

|

Not at all satisfied |

1.481 |

4.40 |

0.000 |

1.205 |

1.756 |

||

|

Ideology |

Left |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Center |

-0.025 |

0.98 |

0.579 |

-0.111 |

0.062 |

||

|

Right |

-0.199 |

0.82 |

0.000 |

-0.296 |

-0.103 |

||

|

Don’t know/No Comment |

0.248 |

1.28 |

0.000 |

0.115 |

0.380 |

||

|

Mivozcuentapais (My voice is heard in my country) |

Yes |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

No |

1.322 |

3.75 |

0.000 |

1.250 |

1.395 |

||

|

CONTEXTUAL VARIABLES |

1.00 |

||||||

|

Tcomunidad (Size of the community of residence) |

Cities |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Towns |

0.234 |

1.26 |

0.000 |

0.149 |

0.318 |

||

|

Rural |

0.280 |

1.32 |

0.000 |

0.194 |

0.367 |

||

|

Estbien (Welfare State Model) |

Nordic |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Continental + Irl |

0.180 |

1.20 |

0.027 |

0.021 |

0.339 |

||

|

Mediterranean |

-0.064 |

0.94 |

0.510 |

-0.253 |

0.126 |

||

|

Eastern Europe |

0.430 |

1.54 |

0.000 |

0.254 |

0.606 |

||

|

Polarizacionpol (Political polarization) |

0=not at all - 4=yes |

0.204 |

1.23 |

0.000 |

0.120 |

0.288 |

|

|

Calidadinst (Institutional quality) |

Less to more quality |

-0.270 |

0.76 |

0.028 |

-0.511 |

-0.029 |

|

|

Estabilpolit (Political stability) |

0=plus b - 100=plus a |

-0.017 |

0.98 |

0.000 |

-0.022 |

-0.012 |

|

|

INTERVENING VARIABLES |

|||||||

|

Infalsa <- |

|||||||

|

MCNinflibppc |

Yes |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

No |

0.824 |

2.28 |

0.000 |

0.768 |

0.881 |

||

|

Polarizacionpol <- |

|||||||

|

Infalsa (You often find news or information that is… fake) |

Disagree |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Agree |

0.142 |

1.15 |

0.000 |

0.126 |

0.158 |

||

|

Calidadinst <- |

|||||||

|

Infalsa (You often find news or information that is… fake) |

Disagree |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Agree |

-0.055 |

0.95 |

0.000 |

-0.061 |

-0.049 |

||

|

Estabilpolit <- |

|||||||

|

Infalsa (You often find news or information that is… fake) |

Disagree |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Agree |

-0.835 |

0.43 |

0.000 |

-1.048 |

-0.622 |

||

|

MCNinflibppc <- |

|||||||

|

Studies |

High |

0.000 |

1.00 |

||||

|

Studying |

-0.077 |

0.93 |

0.147 |

-0.182 |

0.027 |

||

|

Average |

0.303 |

1.35 |

0.000 |

0.247 |

0.359 |

||

|

Low |

0.202 |

1.22 |

0.000 |

0.114 |

0.289 |

||

Source: Author’s own creation.

Table 3. DWD in the country where you live according to the GSEM model (Continuation)

RECEPTION: September 9, 2024

REVIEW: January 16, 2025

ACCEPTANCE: April 7, 2025