doi:10.5477/cis/reis.189.23-42

Gender Ideologies in Spain:

A Latent Class Approach

Ideologías de género en España: Un análisis de clases latentes

Marta Domínguez-Folgueras

|

Key words Gender Ideology

|

Abstract Attitudes towards gender equality are often described as either “traditional” or “egalitarian”, depending on support for separate or joint spheres. Recent research suggests that ideologies are more complex and include multiple dimensions. Using data from the 2018 Fertility Survey, we apply a Latent Class Analysis to study the different dimensions of gender egalitarianism in Spain. We contribute to the literature by considering the role of “family centrality” and by including several indicators that allow us give greater nuance to the interpretation of certain dimensions. The analysis shows that there are five profiles of respondents with different understandings of gender egalitarianism. We also study the sociodemographic characteristics of each of these profiles, showing that sex, age, education, and religiosity are the main variables associated with gender ideology. |

|

Palabras clave Ideología de género

|

Resumen Las actitudes hacia la igualdad de género se suelen describir como tradicionales o igualitarias, dependiendo del acuerdo con la idea de esferas separadas o comunes. Investigaciones recientes sugieren que las ideologías son más complejas e incluyen varias dimensiones. Utilizando los datos de la Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018, se utiliza un análisis de clases latentes para estudiar las diferentes dimensiones del igualitarismo de género en España. De esta forma, se contribuye a la literatura, considerando el papel de la «centralidad de la familia» e incluyendo indicadores adicionales que permiten matizar la interpretación de algunas dimensiones. El análisis muestra que hay cinco perfiles ideológicos, con diferentes concepciones de la igualdad de género. También se estudian las características sociodemográficas de estos perfiles, mostrando que el sexo, la edad, la educación y la religiosidad son las principales variables asociadas a la ideología de género. |

Citation

Domínguez-Folgueras, Marta (2025). «Gender Ideologies in Spain: A Latent Class Approach». Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 189: 23-42. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.189.23-42)

Marta Domínguez-Folgueras: Sciences Po, Centre de Recherche sur les Inégalités Sociales (Paris) |

marta.Domínguezfolgueras@sciencespo.fr

Introduction1

Spanish society has undergone significant changes in the last 50 years, including a move towards more gender equality. Often portrayed as a Southern European country with familistic and traditional values, this description needs greater nuance in light of the very rapid changes in women’s position in society (Jurado-Guerrero, 2007), especially when we observe the behavior of younger cohorts, with rates of economic activity close to the EU average and with values and family formation behaviors that are now less traditional (Moreno Mínguez, 2021; Seiz et al., 2022). Previous research has also revealed a high level of agreement with gender egalitarianism in Spain (Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018).

At the individual level, attitudes towards gender equality, or gender ideologies, have been defined as “the level of support for a division of paid work and family responsibilities that is based on the belief of gendered separate spheres” (Davis and Greenstein, 2009). These ideologies are often characterized along a spectrum in which one extreme would be traditional -if the individual supports a gendered division of work with women specializing in the private sphere and men specializing in paid work- and the other one egalitarian -if the individual supports joint spheres. Recently, some scholars have criticized this approach, arguing that gender ideologies can be more complex (Barth and Trübner, 2018; Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018; Knight and Brinton, 2017; Scarborough, Sin and Risman, 2018; Damme and Papadopoulos, 2023; Yu and Lee, 2013). This scholarship advances the idea that there are multiple dimensions to gender ideology: for instance, someone might agree with women’s participation in paid work on an equal footing with men, but also think that women are better at caring for children.

The above-mentioned scholars approach gender ideologies by highlighting their multiple dimensions. In particular, they take into account three (agreement with gender equality in the public sphere, in the private sphere, and emphasis on free choice), use value surveys (that include Spain), and apply Latent Class Analysis (LCA) to describe the different gender ideologies that can be found in the countries they analyze, finding four or five gender ideologies. Two ideologies correspond to the traditional and egalitarian types, but the others are multidimensional.

This paper contributes to the literature in several ways. We apply LCA to a more recent Spanish dataset, the 2018 Fertility Survey [Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018] (EF), which includes rich data on gender attitudes and allows the use of additional indicators that provide a more fine-grained description of gender ideologies. We also consider an additional dimension that seems relevant in this specific case: family-centrality (familism). After estimating the classes, we analyze the sociodemographic profiles that can be associated with the gender ideology types. The results validate the existence of five profiles but provide additional nuance to their interpretation and point to the need to include other indicators in future surveys and studies.

Different theoretical approaches to gender include beliefs and ideas about gender as central aspects to understand gender inequalities in society. For instance, Ridgeway and Correll (2004) consider that “gender beliefs” contribute to defining the behaviors expected from men and women. Risman (2017) considers gender ideologies as cultural components at the micro and macro levels of gender understood as a social structure. Gender ideologies have also been identified as moderating factors in family and work transitions (Davis and Greenstein, 2009), and are expected to play a role in the adoption and impact of gender equality policies (Campbell, 2012).

Different terminology has been used to refer to attitudes and values toward gender equality, for instance: “gender egalitarianism”, “attitudes towards gender roles”, or “gender ideologies”. These attitudes and values focus mostly on men’s and women’s roles in society, and more specifically in the private and public spheres, although some researchers include additional aspects, for instance, support for state intervention in gender equality (Jakobson and Kostadam, 2010). In this study, we follow Davis and Greenstein (2009) and use the expression “gender ideology” to characterize individuals’ “levels of support for a division of paid work and family responsibilities that is based on the belief in gendered separate spheres”.

Gender ideologies are often described as a scale, where the two extremes are traditionalism and egalitarianism. Individuals with traditional ideologies or beliefs would agree with the idea of gendered spheres, assigning men to the public sphere of paid work, and women to the family sphere and in charge of domestic and care work. People with egalitarian ideologies would not agree with these separate spheres, seeing men and women as equally able to develop activities in both (joint spheres). In quantitative research, to locate individuals on this scale, researchers often use survey items that require respondents to declare their level of agreement with statements about the two spheres. Some examples of statements used in surveys are: “A child will suffer if the mother works” and “Both men and women should contribute to domestic work”. Responses to these items can be aggregated to construct an index, which is then used to place individuals on the traditional-egalitarian continuum.

Multidimensional approaches to gender ideology

Some recent research has criticized this approach to measure gender ideologies because it relies on a single dimension, joint versus separate spheres. Yu and Lee (2013) pointed out that agreement with women’s employment does not necessarily imply agreement with sharing the domestic sphere and separated the two dimensions in their comparative analysis. Following this strategy, Knight and Brinton (2017) introduced an additional element, the idea that different logics could justify women’s assignation to the family sphere and that these justifications were relevant elements to differentiate gender ideologies. Individuals might agree with gender equality in the labor market but also with women taking charge of the domestic sphere if they perceive women as more interested or skilled in this domain. Acknowledgement of these gendered traits has been described as “gender essentialism” (Cotter, Hermsen and Vanneman, 2011). Alternatively, individuals can agree with women’s specialization in the domestic sphere based on personal choice. The importance of women’s “free choice” was highlighted by Charles and Bradley (2009) to explain the persistence of gender segregation in educational tracks. Another dimension added by Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018) is “intensive parenting”. This dimension factors in the spread of intensive motherhood ideology (Hays, 1996), which conflicts with mothers’ working outside the home, as well as the idea that fathers’ are not expected to only be breadwinners; they also need to have an important presence in the home (Wall, 2010), hence the label of “intensive parenthood” and not specifically intensive motherhood.

The multidimensional approach has found evidence of two unidimensional ideologies (traditional and egalitarian), as well as two or more multidimensional ideologies (Barth and Trübner, 2018; Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018; Knight and Brinton, 2017; Scarborough, Sin and Risman, 2018; Damme and Papadopoulos, 2023). Some comparative studies have included the Spanish case. Knight and Brinton (2017) analyzed data from European and World Values Surveys using LCA and considered the role of choice as well as the idea of gendered traits. They defined four gender ideologies. The two unidimensional types, which they labeled “traditional” and “liberal egalitarian”, as well as two multidimensional ideologies. One multidimensional ideology was “egalitarian familist”, with support for equality in the workplace but also a normative imperative for the domestic sphere for women, and the second one was “flexible egalitarian”, which rejected normative imperatives and would agree with any domestic division of work if it was the result of personal choice.

Building on this, Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018) carried out an analysis of the 2011 European Values Study integrating another dimension, intensive parenting. They found five classes, two of which are unidimensional, a traditional and an egalitarian class. Regarding the three multidimensional ideologies, they describe a “moderate traditional class” (belief in separate spheres but less so than the traditional class), an “egalitarian essentialist” class that is very similar to Knight and Brinton’s “egalitarian familists”, and an “intensive parenting” class, for which parents, especially mothers, need to be present for their children.

Recently, Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022) have tried to integrate these two contributions and offer an alternative interpretation of the resulting classes. In their analysis, the different egalitarian types are interpreted in the light of existing approaches to feminism (difference, sameness, and third-wave feminism). Using the European Values Surveys 2011, they define five gender ideologies. In addition to the traditional and the egalitarian unidimensional classes, they identify a “transitional” class, very much equivalent to the intensive parents in Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018). Another class is labeled “difference feminism” (the egalitarian familists in Knight and Brinton) because they hold egalitarian attitudes towards the division of work but justify women being more involved in the domestic sphere. Finally, they describe a third egalitarian class named “third-wave feminists” (which is close to the flexible egalitarians in Knight and Brinton and the egalitarian essentialists in Grunow, Begall and Buchler, 2018), for which choice is a key element that can justify different divisions of work. The unidimensional egalitarian class is labeled “sameness feminism” because it rejects both normative imperatives and women’s specialization in domestic work. Table A in the Appendix summarizes the gender ideologies found in these studies.

Operationalizing the different dimensions

The literature discussed above applies LCA and uses a range of items to measure respondents’ positions about the dimensions that are considered important: support for equality in paid work, support for equality in domestic work, intensive parenthood, and justifications based on free choice or normative imperatives/essentialist notions. To consider the respondents’ positions on these dimensions they use between six and seven survey items (the specific survey items used by each study are listed in Table B in the Appendix). However, it is important to note that measuring these dimensions is complex and that some of them are easier to interpret than others using the available indicators. A common issue is that some items might capture more than one dimension, and therefore they need to be interpreted carefully and in connection with other items. However, there are additional problems that we need to consider: some dimensions can only be measured indirectly or partially; some items apply only to women; and relevance might vary by context.

With existing survey items, some dimensions can only be measured indirectly and partially, which renders interpretation difficult. This is the case of the justifications for the domestic division of work. One justification for traditional arrangements is based on “gendered traits/essentialism”, namely the idea that women are better at care work, or that family is more important for them, captured with statements such as: “Having a job is okay, but what most women want are a home and children” or “men make better political leaders than women”. These gendered characteristics can be perceived as “essential” and rooted in biology, determined by socialization, or a combination of the two. The origin of such gendered characteristics is not asked in surveys, which makes it difficult to conclude if they are perceived as “essential”. Given the data limitations, we will refer to the idea that women are better suited or more interested in the family and the private sphere using the term “gendered traits”, irrespective of their origin.

In turn, opposition to these gendered traits can be associated with the idea of joint spheres, but this is not always the case. Charles and Bradley (2009) pointed out that the idea of freedom of choice could legitimize traditional arrangements and is compatible with the idea of joint spheres. Freedom of choice requires the absence of normative imperatives, otherwise, the choice would not be free. Unfortunately, existing survey items do not provide accurate measurements for freedom of choice. The item used to approximate freedom of choice is “taking care of the family can be as satisfactory as having a paid job”. This item measures agreement with equal value of paid and unpaid work, and it is assumed that if the respondent agrees that both are equally valuable, then this implies that a choice between the two would be a matter of personal preference. However, it could be argued that this item only measures that the satisfaction or value derived from both types of work is the same, and thus, this item only provides an indirect measurement of choice.

A second important issue that needs to be factored in is that some items are not measured symmetrically for men and women. Some survey items that focus only on women can be difficult to interpret, for example, “a woman who works can establish as warm a relationship with her child as a woman who does not work”. Disagreement with this statement can be interpreted as a lack of support for mothers’ employment, but if the respondent also disagrees with the same statement stated for fathers, then this disagreement needs to be understood differently, because it is more about parenting norms and less about gender, given that the respondent has the same opinion about men and women. If we use only the statement about women, we are assuming either that respondents agree with the statement about men, or that the question about men is irrelevant, and both assumptions are problematic. It would be important to have some of these questions asked either symmetrically or with a comparative formulation that provides information on both men and women.

Finally, it must be noted that these approaches have mostly been used with a comparative perspective, including countries that differ significantly in the distribution of the classes. When this perspective is applied to a single case, we can see more nuances and take into account the specific context. Barth and Trübner (2018) have applied this type of analysis to the German case, showing important differences between West and East Germany. When we factor in the specific characteristics of one country, additional dimensions might be relevant. In the case of Spain, we hypothesize that the great importance and centrality accorded to the family (that we will label “family-centrality”) might also be an important component of gender ideology.

The Spanish case is of particular interest in regarding gender ideologies because of the rapid changes that have occurred in terms of family changes and women’s participation in the labor market. Although Spain has been slower to transition towards post-materialistic values than other countries (Cantijoch and San Martin, 2009), there has been a dramatic change in terms of women’s participation in the public sphere since the end of the dictatorship in the late 70s (Jurado-Guerrero, 2007). The country has also integrated gender equality in legislation, for instance, concerning violence against women and the equalization of paternity and maternity leaves. As a result, it has been described as less familistic than Italy, to which it is often compared (León and Pavolini, 2014). However, some social domains, like the division of domestic work, have been more resistant to change (García-Román, 2023) and gender issues also spark public debate, pointing to different gender ideologies coexisting in Spain. Previous research has shown that gender beliefs are moving in an egalitarian direction in Spain, although this is not yet indicated in a more egalitarian distribution of work (Aristegui et al., 2019; Domínguez-Folgueras, 2010).

Knight and Brinton (2017) compared European Values Surveys between 1990 and 2009 and showed that the percentage of respondents that belong to the traditional class had decreased in Spain, from close to 30 % in 1990 to less than 10 % in 2009. In turn, the number of respondents that are classified as egalitarian increased during the period. Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018) and Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022) using data from 2011, also find that the traditional class is very small in the Spanish case (constituting between 9.7, and 3.5 % of respondents).

Regarding other ideologies, the three studies discussed above do not identify the same classes, and therefore the figures cannot be meaningfully compared, so we will use Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022) as a reference because they try to integrate the preceding approaches. Their study finds one class they label “transitional”, which is located between traditional and egalitarian beliefs, agreeing with men specializing more in paid work but also being present in the domestic sphere, based on gendered traits rather than on choice, and comprising 23.5 % of respondents. Regarding egalitarian ideologies, the class labeled “sameness feminism” (agreeing with joint spheres and not approving of women specializing in homemaking) was the most populated one, comprising 39 % of respondents. According to their estimation, respondents who agreed with joint spheres but also with women specializing more in unpaid work because of normative imperatives (difference feminists) were a very important category: 21 % of respondents. Third-wave feminists, who would agree with any division of paid and unpaid work, as long as it was a personal choice, were a very small category, constituting only 6.6 % of respondents.

As noted above, the main aim of this line of research has been to compare countries. However, analyzing one single case in more detail can be illuminating to test the validity of the already identified ideologies, give greater nuance to their meaning, and consider other dimensions that might be of relevance. In particular, family-centrality might be an important dimension to account for in the case of Southern European countries, and thus for Spain. Analyses of gender ideology often include statements about the importance of having children for women or considering the effects that maternal employment might have on children. These survey items are useful to measure agreement with mothers being employed outside the home, but they might also address family-centrality, for instance, if respondents also agree that having children is central for men, that men’s employment has an impact on children, or that family should be a priority for men as well. Family-centrality is thus different from intensive parenting as defined by Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018), because it can be used to justify both traditional family arrangements and non-traditional ones, depending on the circumstances and the combination of this dimension with other beliefs. It is more about the importance of children and the family than about the domestic division of work or specific parenting styles, and to measure this dimension we need symmetrical statements about men and women. In this study, we include family-centrality as an additional dimension to explore gender ideologies in Spain.

Correlates of gender ideologies

The sociodemographic correlates of gender ideologies remain relatively unexplored, but the literature has already identified some relevant factors. In their foundational article on gender ideologies, Bolzendhal and Myers (2004) argue that gender ideologies can be influenced by two mechanisms: interest and exposure. Interest would imply that those who can gain more from gender equality will hold more egalitarian beliefs. Thus, given existing gender inequalities, we can expect that women will have more egalitarian views, that women who are active in the labor market will be more supportive of women’s labor market participation, and that women living in a couple will support more gender equality in the home. In turn, exposure entails that being exposed to egalitarian (or traditional) ideas, through education, personal experiences, or socialization, will lead to the development of beliefs in line with those ideas. According to this mechanism, factors like parents’ gender ideologies, education, and religiosity are likely to impact individuals’ gender ideologies.

Davis and Greenstein (2009), in their review of the literature, point to some of these variables showing consistent associations with gender ideologies: educational attainment and labor force participation are positively associated with more egalitarian ideologies, whereas age and religiosity are negatively associated with gender egalitarianism. Marital status and parenthood have shown mixed results, although these life transitions have been shown to lead to more traditional behaviors in terms of the domestic division of labour.

These results are based on a unidimensional definition of gender ideologies; their relationship to more complex, multidimensional ideologies has been analyzed only by Knight and Brinton (2017). For the 17 European countries in their study, controlling for country, wave, and other characteristics, they found that women, unmarried individuals, full-time workers, those who declared no religious affiliation, and higher-income respondents were more likely to be members of the liberal egalitarian or the flexible egalitarian class. In turn, men, respondents with children, and those who did not work full-time were more likely to belong to the traditional class and to the egalitarian familist class. Political values were also associated with gender ideologies, with left-leaning individuals more likely to be in the liberal egalitarian class and those with conservative values more likely to be in the traditional one. Finally, age also played a role, with younger respondents more likely to be in the flexible egalitarian class.

In line with his literature, we expect to find more egalitarian ideologies among women, the highly educated, younger cohorts, the unmarried, and less religious individuals.

In this study, we use data from the 2018 Fertility Survey carried out by Spain’s National Statistics Institute [Instituto Nacional de Estadística] (INE). The survey takes a similar approach to the Gender and Generations Programme, including rich information on labour market participation, fertility, and household composition. The survey was carried out in 2018 and gathered information from 14556 women and 2619 men aged 18-55. The sample of women is larger, which is often the case in fertility surveys, but both samples are representative (INE, 2019).

The survey includes 12 items about gender beliefs, with three possible outcomes (agree, neither agree nor disagree, and disagree). These items have some advantages compared to those used in previous surveys, but they are not perfect. Some items that have often been asked only to women in previous studies are also asked to men here; this will allow us to control for the “family-centrality” dimension, as well as to give greater nuance to the interpretation of female-centred indicators. However, the items also suffer from some of the problems identified previously, as we will see. The items are the following:

To carry out the analysis and following the previous studies that have used the LCA approach, we recoded the variables as dichotomous (with 1 being the most egalitarian answer, and 0 otherwise). In the case of the item measuring the importance of choice -“taking care of the home and the family is just as fulfilling as working for pay”-, it was coded 1 if the respondent agreed, and 0 otherwise. There were no missing values in the responses to these items.

The data were recoded using the statistical software Stata, and then the LCA analysis was performed using Latent Gold (the Stata syntax, as well as the options used, are available upon request). Following the recommendations for this type of analysis (Nylund and Choi, 2018; Weller, Bowen and Faubert, 2020), to find the best model, we started by fitting a model with one class and added one additional class in each step until the model fit and classification indicators stopped improving. To choose the best model, there are a variety of indicators that can be used, although the BIC is the most common one. Table 1 shows the BIC and the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (VLRM) adjusted likelihood ratio test for all the models. The VLRM test p-value indicates if a model with n-classes is statistically better than the model with n-1 classes, based on Monte Carlo simulations of 500 samples. The BIC decreases with additional classes, although the decrease becomes less pronounced after the four-class solution. The VLRM test is significant for all models.

Table 1 also presents some classification diagnostics (entropy and classification error), which are not used for model selection but provide information that needs to be considered. These diagnostics point to the 5-class solution as the limit, with a 10 % error and entropy over 0.80. Taking these indicators into account, we then examined the models between 4 and 6 classes, to check which one was more relevant theoretically. All the models identify a traditional and an egalitarian class but differ in terms of the multidimensional classes. The 5-class solution includes three multidimensional classes. In the 4-class solution, one of these classes is not visible. The 6-class solution is similar to the 5-class one, but also identifies a very small, very egalitarian class, with a distinctive response pattern for one item that is difficult to interpret (it is the most egalitarian class, but respondents agree less than the average with the idea that domestic work should be equally shared). Given these class configurations, we decided to keep the 5-class solution as the most theoretically relevant, although it is important to note that both the 4 and 6-class solutions would be viable as well.

As a second step, using the marginal probabilities predicted by the model, we computed a variable that assigns each respondent to the most likely class. Each of the five classes defines one distinct gender ideology. Table 2 shows the average posterior probability of belonging to each class. All the probabilities are above 0.80, which is considered an acceptable level (Weller, Bowen and Faubert, 2020), with a lower probability for class 4. It is important to note that this is the class that was not included in the 4-class solution.

To explore the sociodemographic correlates of each ideology, we use a three-step approach (Vermunt, 2010). This strategy involves finding first the latent class model that fits best and saving the results and predicted probabilities. The final step is estimating a multinomial logistic model to predict class membership with the covariates of interest, considering the classification errors that class attribution implies. This approach is considered more accurate for describing predictors of class membership than just using the predicted classes as dependent variables in statistical models (Vermunt, 2010).

For the covariates, we use other questions from the survey. Sex is measured with a binary variable (0 for women, 1 for men) as indicated in the survey, which ran separate questionnaires for women and men. The questionnaire includes information on children, including biological and adopted children. We create a dichotomous variable with the value 1 if the person has ever had a child (biological or adopted) and 0 otherwise. Regarding the type of union, respondents were asked to indicate if they were living with a partner and the type of union, which allows us to create a variable with four different outcomes (not living with a partner, married, registered cohabitation, and unregistered cohabitation). For paid work, we use one variable that measures if the respondent is working for pay, with the value 1 if the respondent is working, and 0 otherwise. Finally, to measure religiosity, we use responses to the question: “Regarding your religious practice, how observant would you consider yourself to be?”, with responses on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very). We created a binary variable with the value 1 for those who declared being quite observant or very observant, and 0 for those who were not observant or only a bit, as well as those not affiliated with any religion. Missing values are included as a category in the variables concerned. Table 3 presents the distribution of the sample.

We first describe the classes we have identified and then we analyse the sociodemographic profiles of respondents within each class.

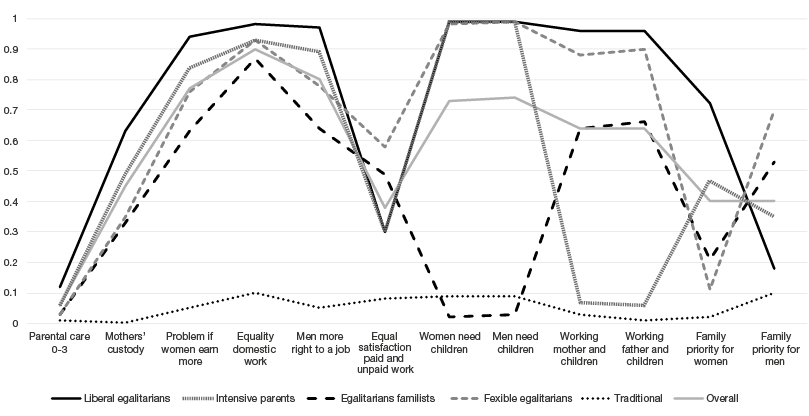

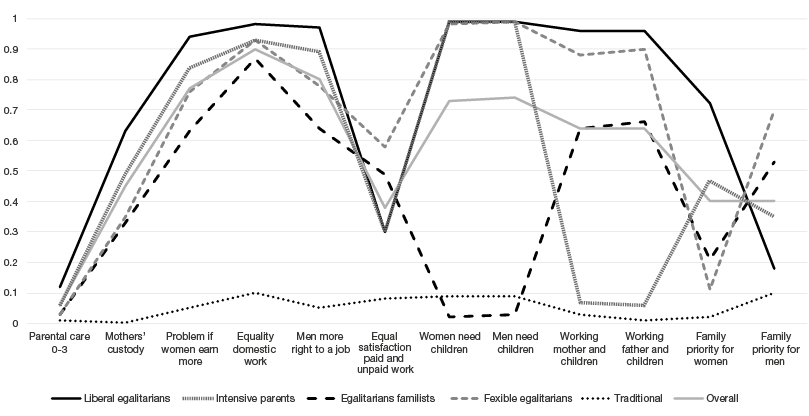

The analysis identifies five classes, which we have labelled “traditional”, “egalitarian familist”, “flexible egalitarian”, “intensive parenting” and “liberal egalitarian”. Figure 1 shows the probability of giving an egalitarian answer to each item for the five classes. It is important to note that respondents provided very egalitarian answers overall, but one variable stands out: the idea that parents should be the main carers for children under 3, with only 7 % of respondents disagreeing. This is an item that can be interpreted as an indicator of intensive contemporary norms on parenthood. The figure shows the average for the whole sample as well, for reference.

1) Traditional

We label this group “traditional” because respondents report much more traditional answers than the average in all dimensions. In this group, we find very low levels of agreement with joint spheres, and high levels of family-centrality (having children is important both for women and men, family is more important than paid work for both, and parents should be the main carers). Women are identified as more in charge of care work (in case of separation, children should go with the mother and family is a priority for women more than for men), but there is disagreement with the idea that the home and paid work are equally satisfying, so the two spheres are gendered and do not have the same value. This group is very small, including only 4.75 % of respondents, and it seems equivalent to the traditional class found in previous studies.

2) Liberal egalitarians

This group shows the highest probability of giving egalitarian answers to all items. They cannot be considered as very family-centred because they do not think that having children is necessary to feel fulfilled, nor that family should be a priority for anyone, and show a low level of agreement with the idea that family and paid work are equally satisfying. This is the largest group, including 32 % of respondents, and they are very similar to the liberal egalitarians in Knight and Brinton (2017), the egalitarian class in Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018), and the second-wave feminists in Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022).

3) Egalitarian familists

This group’s responses are a bit less likely to be egalitarian than the average in all dimensions, but they are much closer to the average than the traditionals. What differentiates the response patterns of this group is the importance accorded to children for both men’s and women’s lives. They are also less likely than other egalitarian groups to think that parents who work can have as warm a relationship with their children as parents who do not work. There are some indications of a belief in gendered traits, because they are more likely than the average respondent to think that family is a priority for women (and less so for men), and they are also more likely to think that the mother should retain custody of the children in case of divorce than other egalitarian classes, but much less so than traditionals. This class shares many characteristics of the “egalitarian familists” described by Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018), and of the “difference feminists” described by Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022), although the belief in gendered traits seems to be less marked here. This group comprises 22 % of the sample.

4) Flexible egalitarians

Respondents in this group are close to liberal egalitarians in most items. What is specific to this group is that they show the highest level of agreement with the idea that taking care of the home can be as fulfilling as working for pay, and they are more likely to say that family should be a priority for both women and men. It seems that this this group would agree with specialization as a choice, and consider having children as a choice. This agreement with joint spheres of equal value makes them close to Damme and Pavlopoulos’ third-wave feminists (2022) or flexible egalitarians (Knight and Brinton, 2017). 19 % of the sample is included in this group.

5) Intensive parents

This group is very close to liberal egalitarians in all items, with some important differences. Despite their egalitarian take on paid work, and much like the traditional group, this group shows a very low likelihood of agreeing with the idea that parents who work can have as warm a relationship with their children as parents who do not work, and they provide similar answers for both mothers and fathers. They also agree more with the idea that family should be a priority for men and women. This leads us to interpret these respondents as intensive parents, similar to the class identified by Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018). This group comprises 21.43 % of respondents.

Thus, together with a traditional and a liberal class, we find three multidimensional classes. The three agree with equality in paid work and unpaid work but with some differences. For one of the egalitarian classes -egalitarian familists- family is central for both women and men (it is important to have children, family should be a priority, and paid work has consequences on family relations). For another class -intensive parents-, having children is not crucial, but they see a strong incompatibility between paid work and children, again for both mothers and fathers. Finally, the third egalitarian class -flexible egalitarians- shows some signs of accepting some inequality in the private sphere, seeing family as more important for women and agreeing with the idea that paid and unpaid work are equally satisfactory.

Table 4 summarizes the different classes and dimensions found in previous research and also the results from this article.

To analyse the sociodemographic structure of each class, we present the results from the 3-step approach. Table 5 shows the predicted class profiles for the Latent Class Models including the covariates of interest. Regression coefficients are included in the Appendix, Table C.

Results show that respondents in the liberal egalitarian class are more likely to be women, younger, highly educated, and living in a non-registered partnership than members in the other classes. Respondents in the traditional class are more likely to be men, from older cohorts, religious, and with lower educational attainment than the liberal egalitarians. Intensive parents are similar to liberal egalitarians, but they are more balanced in terms of gender, with lower educational attainment, and with fewer respondents in the youngest cohorts. Egalitarian familists and flexible egalitarians are more likely to be married and to have lower levels of education and religiosity, with an age distribution that is more like the traditional class. Flexible egalitarians are also less likely to have children and to be employed than the other classes and have the highest average age. Religiosity is an interesting variable here because, although we find more religious respondents in the traditional group, the liberal egalitarians are not the least religious. Except for religiosity, the relationship between the covariates and the classes is in line with the findings in Knight and Brinton (2017), with an interesting pattern found for the flexible egalitarians, who have lower educational attainment, are a bit older, have fewer children, are less likely to be working but are also less religious.

This study has analysed gender egalitarianism in Spain using data from the 2018 Fertility Survey, representative of the Spanish population aged between 18 and 55. Following previous scholarship, we have applied a multidimensional approach, including several dimensions in the analysis: agreement with separate or joint spheres for paid and unpaid work, justifications for this in terms of gendered traits, the equal value of both spheres, and intensive parenthood. Expanding this literature, we add family-centrality (the importance of family and children) as a relevant dimension to explore in the Spanish case. The analyses show that there are multiple gender ideologies in Spain, and we chose the five-class solution as the most relevant theoretically.

The five classes correspond to five gender ideologies. The “traditional” class shows agreement with familism and with gendered spheres based on gendered traits. The “liberal egalitarian” class shows low levels of familism and high levels of agreement with equality in both paid and unpaid work. We find three egalitarian classes that are multidimensional. An “egalitarian familist” class agrees with joint spheres but also with family centrality, although still considering women as having greater responsibility fore domestic tasks, with some gendered traits regarding the private sphere. “Flexible egalitarians” agree with joint spheres and gender equality both at home and in paid work, and they show low levels of familism. Family is a choice for them, and the domestic sphere is given the same value -in terms of the satisfaction derived from it- as the public one. We have labelled the last class “intensive parents” because they agree with joint spheres and show low levels of family-centrality, but they think that parents working for pay cannot have as warm a relationship with children as parents who do not work. Family is a choice, but this class seems to consider that, if that choice is made, parents cannot have it all. Regarding the correlates of the classes, we found that women, younger respondents, and those living in an unregistered cohabiting union were more likely to belong to more egalitarian classes, whereas men, more religious respondents, and those with lower education were more likely to be in the more traditional classes. Highly educated respondents were more likely to belong to the extremes, the liberal egalitarian and the traditional class.

These classes validate previous results from the literature, pointing to the existence of two unidimensional classes, one being a very small traditional one, and to the complexity of egalitarian ideologies that can be observed in the composition of the additional classes. All egalitarian classes agree with equality in paid work, but there are differences in terms of the domestic sphere and the paid-unpaid work interface. The three multidimensional classes we identify are quite similar to the ones described in the literature, but the inclusion of additional items about men and family-centrality has allowed us to provide additional nuances. We found that the presence of gendered traits in the response patterns of the egalitarian familists was not completely consistent: they agreed more with the idea that family should be a priority for women than for men, but then they do not make this difference for working parents, or for the need to have children, and they are close to the average in agreeing that mothers should retain custody in case of divorce. It would seem then that they are more familist than essentialist. For the “flexible egalitarian” group, their agreement with the idea that having children is not central for women could have been interpreted as a feminist stance, or as opposition to gender roles, but the fact that men in this group provide similar answers would point more to a rejection of compulsory parenthood and to the idea of having children as a choice. The class that we have labelled “intensive parents” is also interesting in this sense too, because it illustrates the difference between family-centrality and parenting norms: respondents in this class see having children as a choice for both women and men, while at the same time acknowledging that participating in paid work has costs for the family.

This study also has important limitations. The survey analysed includes only the population between 18 and 55, so it does not provide a full picture of Spanish society. It includes many items on gender values, but they have limitations, many of them measure more than one dimension, and some measures are only indirect. This is especially the case for the logic of justification, as the indicator of free choice is problematic, and there is no direct question on essentialism or the origin of sex differences. In terms of survey design, it seems important that future surveys include more precise items on these dimensions. Finally, although we have selected the 5-class configuration as the best solution, four or six classes could also have been explored, which would result in some different groups, although all possible solutions illustrate the multidimensionality of contemporary gender ideologies.

The multidimensionality of gender ideologies applied to Spain could provide some insight into current family and paid work changes. For instance, the rejection of the centrality of children, and the idea that having children is a choice and to some degree incompatible with paid work that we find within some types, can be of interest to understand fertility and family formation decisions. Previous research has shown that Spanish mothers may adjust their fertility intentions by taking into account the structural constraints they face (Campillo and Armijo, 2017), and we can hypothesize that fertility behaviour might also be mediated by gender ideology. Unpaid domestic and care work are also outcomes that have been associated with gender ideology, and the multidimensional approach could be applied to this issue. Including questions on gender ideology in general surveys is necessary to analyse its role as mediator in other social phenomena, like domestic work or family transitions.

Bibliography

Aristegui Fradua, Iratxe; Beloki Marañón, Usue; Royo Prieto, Raquel and Silvestre Cabrera, Maria (2019). “Cuidado, valores y género: La distribución de roles familiares en el imaginario colectivo de la sociedad española”. Inguruak. Revista Vasca de Sociología y Ciencia Política, 65: 90-108.

Barth, Alice and Trübner, Miriam (2018). “Structural Stability, Quantitative Change: A Latent Class Analysis Approach towards Gender Role Attitudes in Germany”. Social Science Research, 72: 183-193.

Bolzendahl, Catherine and Myers, Daniel (2004). “Feminist Attitudes and Support for Gender Equality: Opinion Change in Women and Men, 1974-1998”. Social Forces, 83: 759-789.

Campbell, Andrea Louise (2012). “Policy Makes Mass Politics”. Annual Review of Political Science, 15: 333-351.

Campillo, Inés and Armijo, Lorena (2017). “Lifestyle Preferences and Strategies of Spanish Working Mothers: A Matter of Choice?”. South European Society and Politics, 22: 81-99.

Cantijoch, Marta and San Martin, Josep (2009). “Postmaterialism and Political Participation in Spain”. South European Society and Politics, 14: 167-190.

Charles, Maria and Bradley, Karen (2009). “Indulging Our Gendered Selves? Sex Segregation by Field of Study in 44 Countries”. American Journal of Sociology, 114: 924-976.

Cotter, David; Hermsen, Joan and Vanneman, Reeve (2011). “The End of the Gender Revolution? Gender Role Attitudes from 1977 to 2008”. American Journal of Sociology, 117: 259-289.

Damme, Maike and Pavlopoulos, Dimitris (2022). “Gender Ideology in Europe: Plotting Normative Types in a Multidimensional Space”. Social Indicators Research, 164: 861-891.

Davis, Sharon and Greenstein, Theodor (2009). “Gender Ideology: Components, Predictors, and Consequences”. Annual Review of Sociology, 35: 87-105.

Domínguez-Folgueras, Marta (2010). “¿Cada vez más igualitarios? Los valores de género de la juventud y su aplicación en la práctica”. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 90: 103-122.

García-Román, Joan (2023). “Does Women’s Educational Advantage Mean a More Egalitarian Distribution of Gender Roles? Evidence from Dual-earner Couples in Spain”. Journal of Family Studies, 29(1): 285-305.

Grunow, Daniela; Begall, Katia and Buchler, Sandra (2018). “Gender Ideologies in Europe: A Multidimensional Framework”. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80: 42-60.

Hays, Sharon (1996). The Cultural Contradictions of Motherhood. New Haven: Yale University Press.

INE (2019). Encuesta de Fecundidad y Valores 2018. Metodología. Madrid: Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Available at: https://www.ine.es/metodologia/t20/fecundidad2018_meto.pdf, access March 20, 2019.

Jakobsson, Niklas and Kotsadam, Andreas (2010). “Do Attitudes toward Gender Equality Really Differ between Norway and Sweden?”. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(2): 142-159.

Jurado Guerrero, Teresa (2007). Cambios familiares y trabajo social. Madrid: Ediasa.

Knight, Carly and Brinton, Mary (2017). “One Egalitarianism or Several? Two Decades of Gender-Role Attitude Change in Europe”. American Journal of Sociology, 122: 1485-1532.

León, Margarita and Pavolini, Emmanuele (2014). “«Social Investment» or Back to «Familism»: The Impact of the Economic Crisis on Family and Care Policies in Italy and Spain». South European Society and Politics, 19: 353-369.

Moreno Mínguez, Almudena (2021). “Hacia una sociedad igualitaria: Valores familiares y género en los jóvenes en Alemania, Noruega y España”. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 79: e190.

Nylund-Gibson, Karen and Choi, Andrew (2018). “Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis”. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4): 440-461.

Ridgeway, Cecilia and Correll, Shelley (2004). “Unpacking the Gender System: A Theoretical Perspective on Gender Beliefs and Social Relations”. Gender and Society, 18: 510-531.

Risman, Barbara (2017). Gender as a Social Structure. In: B. Risman, C. Froyum and W. Scarborough (eds.). Handbook of the Sociology of Gender. Cham: Springer.

Scarborough, William; Sin, Ray and Risman, Barbara (2019). “Attitudes and the Stalled Gender Revolution: Egalitarianism, Traditionalism, and Ambivalence from 1977 through 2016”. Gender and Society, 33(2): 173-200.

Seiz, Marta; Castro-Martín, Teresa; Cordero-Coma, Julia and Martín-García, Teresa (2022). “La evolución de las normas sociales relativas a las transiciones familiares en España”. Revista Española de Sociología, 31(2): 1-28.

Vermunt, Jeroen (2010). “Latent Class Modeling with Covariates: Two Improved Three-Step Approaches”. Political Analysis, 18(4): 450-469.

Wall, Glenda (2010). “Mothers’ Experiences with Intensive Parenting and Brain Development Discourse”. Women’s Studies International Forum, 33: 253-263.

Weller, Bridget; Bowen, Natasha and Faubert, Sarah (2020). “Latent Class Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice”. Journal of Black Psychology, 46(4): 287-311.

Yu, Wei-hsin and Lee, Pei-lin (2013). “Decomposing Gender Beliefs: Cross-National Differences in Attitudes Toward Maternal Employment and Gender Equality at Home”. Sociological Inquiry, 83: 591-621.

Table A. Gender ideologies described in the three international comparisons and equivalences*

|

Ideologies described: |

Paid work |

Unpaid work |

Justifications |

Other |

|||

|

Separate |

Joint |

Separate |

Joint |

Choice |

Gendered traits |

Intensive parenting |

|

|

Traditional¹, ², ³ |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Transitional¹/Intensive parents²/--- |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Sameness feminism¹/Egalitarian²/Liberal egalitarian³ |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Difference feminism¹/--/Egalitarian familist³ |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Third wave feminism¹/Egalitarian essentialist²/Flexible egalitarian³ |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

¹ Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022), ² Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018), ³ Knight and Brinton (2017).

*Adapted from Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022).

Table B. Items used in the three comparative studies

|

VDP1 |

GBB2 |

KB3 |

This paper |

|

|

Both men and women should contribute to the household income. |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

When jobs are scarce, men have more rights to a job. |

X |

X |

||

|

Fathers are as well suited to look after their children as mothers. |

X |

X |

||

|

Men should take as much responsibility as women for the home and kids. |

X |

X |

||

|

A working mother can establish just as warm a relationship with her child as a mother who does not work. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

A preschool child suffers if his/her mother works. |

X |

X |

||

|

A job is all right, but most women want a home and children. |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Being a housewife is just as fulfilling as working for pay. |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

Having a job is the best way for a woman to be an independent person. |

X |

X |

||

|

Do you think that a woman has to have children to be fulfilled? |

X |

X |

Table C. Logit coefficients for the 3-step model with covariates (multinomial regressions, N=17175)

|

Intensive parents vs. liberal egalitarians |

Standard errors |

Egalitarian familists vs. liberal egalitarians |

Standard errors |

Flexible egalitarians vs. liberal egalitarians |

Standard errors |

Traditionals vs- liberal egalitarians |

Standard erros |

|

|

Sex |

||||||||

|

Women |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

||||

|

Men |

0.3383 |

0.0013 |

0.5440 |

0.0013 |

0.2032 |

0.0018 |

0.6561 |

0.0023 |

|

Partnership status |

||||||||

|

No partner |

0.0117 |

0.0017 |

-0.1943 |

0.0017 |

-0.0476 |

0.0022 |

0.2359 |

0.0029 |

|

Married |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

||||

|

Registered cohabitation |

0.2816 |

0.0047 |

0.1860 |

0.0047 |

0.2142 |

0.0060 |

0.660 |

0.0068 |

|

Unregistered cohabitation |

0.0037 |

0.0017 |

-0.3974 |

0.0018 |

-1.2857 |

0.0023 |

-0.2562 |

0.0033 |

|

Has children |

-0.0308 |

0.0013 |

0.1656 |

0.0013 |

-0.1634 |

0.0018 |

0.0531 |

0.0022 |

|

Educational attainment |

||||||||

|

Primary |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

||||

|

Secondary |

-0.812 |

0.0020 |

-1.0180 |

0.0020 |

-1.1166 |

0.0024 |

-1.0667 |

0.0029 |

|

Tertiary |

-1.1929 |

0.0021 |

-1.6443 |

0.0021 |

-2.1766 |

0.0030 |

-1.3489 |

0.0032 |

|

Religiosity |

||||||||

|

Not religious |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

ref. |

||||

|

Quite or very religious |

-0.1329 |

0.0013 |

-0.5651 |

0.0013 |

-0.6129 |

0.0018 |

0.6618 |

0.0024 |

|

In paid work |

-0.0581 |

0.0015 |

-0.1125 |

0.0015 |

-2.334 |

0.0020 |

-0.2050 |

0.0025 |

|

Age |

0.0168 |

0.0001 |

0.0252 |

0.0001 |

0.0384 |

0.0001 |

0.0398 |

0.0001 |

|

Intercept |

-0.2129 |

0.0038 |

-0.1936 |

0.0040 |

-0.3472 |

0.0051 |

-3.1436 |

0.0068 |

1 This reesearch has received funding from the Ministery for Science and Innovation, PID2020-119339GB-C21.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 189, January - March 2025, pp. 23-42

Table 1. Fit indices for the LCA

|

BIC |

VLRM |

(p-value) |

Entropy |

Error in class prediction |

|

|

1- class model |

324345840 |

_ |

0.000 |

||

|

2- class model |

290521437 |

33824623 |

0.000 |

0.96 |

0.007 |

|

3- class model |

279861208 |

10660449 |

0.000 |

0.92 |

0.023 |

|

4- class model |

273524195 |

6337233 |

0.000 |

0.93 |

0.024 |

|

5- class model |

270293177 |

3231239 |

0.000 |

0.83 |

0.104 |

|

6- class model |

267721968 |

2571430 |

0.000 |

0.81 |

0.128 |

|

7- class model |

264742181 |

1799817 |

0.000 |

0.81 |

0.127 |

|

8- class model |

270293177 |

1180410 |

0.000 |

0.80 |

0.142 |

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

Table 2. Average posterior probabilities for the 5 class-solution, by class

|

Class1 |

Class2 |

Class 3 |

Class 4 |

Class 5 |

|

|

Liberal egalitarian |

0.8321 |

0.0292 |

0.0020 |

0.1368 |

0.0000 |

|

Egalitarian familist |

0.0420 |

0.8999 |

0.0070 |

0.0480 |

0.0031 |

|

Intensive parents |

0.0029 |

0.0071 |

0.9603 |

0.0115 |

0.0182 |

|

Flexible egalitarian |

0.2375 |

0.0578 |

0.0137 |

0.6905 |

0.0005 |

|

Traditional |

0.000 |

0.0147 |

0.0847 |

0.0019 |

0.8987 |

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

Table 3. Sample distribution (weighted)

|

Distribution |

|

|

Sex |

|

|

Women |

84.75 |

|

Men |

15.25 |

|

Partnership status |

|

|

No partner |

26.87 |

|

Married |

48.98 |

|

Registered cohabitation |

2.14 |

|

Unregistered cohabitation |

22.01 |

|

Has children |

51.07 |

|

Educational attainment |

|

|

Primary |

24.19 |

|

Secondary |

44.61 |

|

Tertiary |

31.21 |

|

Religiosity |

|

|

Not religious or not very religious |

54.08 |

|

Quite or very religious |

45.02 |

|

Is working for pay |

64.89 |

|

Age (average) |

39.08 |

|

N |

17175 |

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

Figure 1. Probability of providing an egalitarian answer to each item, by class

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

Table 4. Gender ideologies described

|

Paid work |

Unpaid work |

Justifications |

Other dimensions |

|||||

|

Ideologies described: |

Separate |

Joint |

Separate |

Joint |

Choice |

Gendered traits |

Intensive parenting |

Family-centrality |

|

Traditional |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||||

|

Egalitarian familist |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|||

|

Flexible egalitarian |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Intensive parenting |

X |

X |

X |

|||||

|

Liberal egalitarian |

X |

X |

||||||

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

Table 5. Class profiles by covariates

|

Liberal egalitarian |

Intensive parents |

Egalitarian familists |

Flexible egalitarian |

Traditional |

Overall |

|

|

Sex |

||||||

|

Men |

0.5760 |

0.4746 |

0.4273 |

0.5113 |

0.3924 |

0.4978 |

|

Women |

0.4924 |

0.5254 |

0.5727 |

0.4887 |

0.6076 |

0.5022 |

|

Partnership status |

||||||

|

No partner |

0.3006 |

0.2822 |

0.2534 |

0.2625 |

0.3349 |

0.2805 |

|

Married |

0.3925 |

0.4370 |

0.5328 |

0.5393 |

0.4578 |

0.4655 |

|

Registered cohabitation |

0.0162 |

0.0205 |

0.0205 |

0.0188 |

0.0287 |

0.0192 |

|

Unregistered cohabitation |

0.2907 |

0.2603 |

0.1897 |

0.1795 |

0.1787 |

0.2348 |

|

Has children |

0.5410 |

0.5337 |

0.5801 |

0.4988 |

0.5588 |

0.5409 |

|

Educational attainment |

||||||

|

Primary |

0.1073 |

0.2603 |

0.3445 |

0.4015 |

0.3196 |

0.2596 |

|

Secondary |

0.4805 |

0.4631 |

0.4462 |

0.4571 |

0.4087 |

0.4612 |

|

Tertiary |

0.4112 |

0.2766 |

0.2094 |

0.1415 |

0.2717 |

0.2792 |

|

Religiosity |

||||||

|

Quite or very religious |

0.5634 |

0.5143 |

0.3948 |

0.3697 |

0.6931 |

0.4847 |

|

Is working for pay |

0.7035 |

0.6983 |

0.7024 |

0.6553 |

0.6806 |

0.6919 |

|

Age |

||||||

|

18-27 |

0.2802 |

0.1881 |

0.1249 |

0.1372 |

0.1455 |

0.1919 |

|

28-36 |

0.2265 |

0.2357 |

0.2283 |

0.1662 |

0.2099 |

0.2167 |

|

37-42 |

0.1795 |

0.2108 |

0.1998 |

0.1799 |

0.1951 |

0.1918 |

|

43-48 |

0.1595 |

0.1853 |

0.2118 |

0.2269 |

0.1883 |

0.1909 |

|

49-55 |

0.1542 |

0.1800 |

0.2354 |

0.2898 |

0.2612 |

0.2086 |

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

RECEPTION: June 23, 2023

REVIEW: February 13, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: May 3, 2024

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

¹ Damme and Pavlopoulos (2022), ² Grunow, Begall and Buchler (2018), ³ Knight and Brinton (2017) .

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.

Source: Prepared by the author using data from the Encuesta de Fecundidad 2018.