doi:10.5477/cis/reis.189.63-92

The Spanish Anti-Rights Field. Protest Cycle and Networks of Catholic-Inspired Neoconservative Organisations (1978-2023)

El campo antiderechos en España: ciclo de protesta y redes de organizaciones neoconservadoras de inspiración católica (1978-2023)

Joseba García Martín and Ignacia Perugorría

|

Key words Social Mobilisation

|

Abstract This article analyses the protest cycle (1978-present) of the Spanish field of Catholic-inspired secular organisations that espouse neo-conservative ideology (CISO-Ns) against progressive morality politics. To do so, it relies on a comparative-historical and relational approach that focuses on the evolving interplay between 1) cultural and political opportunity structures; 2) the network structure and dynamics of the CISO-N field, and its “expanded anti-rights field” composed of religious and political organisations; and 3) their tactical-discursive triangulation. The research is based on a qualitative study involving in-depth interviews, participant observation and netnography. Data show that, far from being mere conveyor belts for the ecclesiastical message, or being at the service of conservative political parties, CISO-Ns lead a complex strategy based on the “re-politicisation of religion” following a logic of their own. |

|

Palabras clave Movilización social

|

Resumen El artículo analiza el ciclo de protesta (1978-actualidad) del campo de organizaciones laicas de inspiración católica e ideología neoconservadora (OLIC-N) español contra las políticas morales progresistas. Para ello, utiliza un enfoque histórico-comparativo y relacional, centrándose en la cambiante interacción entre 1) estructuras de oportunidad cultural y política; 2) estructura y dinámica de red del campo OLIC-N, y su «campo ampliado antiderechos», compuesto por organizaciones religiosas y políticas; y, 3) su triangulación táctico-discursiva. La investigación se basa en un estudio cualitativo que comprende entrevistas en profundidad, observación participante y netnografía. Los datos muestran que, lejos de ser meras correas de transmisión del mensaje eclesiástico, o de estar al servicio de los partidos políticos conservadores, las OLIC-N lideran una compleja estrategia de «repolitización de lo religioso», de acuerdo con una lógica propia. |

Citation

García Martín, Joseba; Perugorría, Ignacia (2025). «The Spanish Anti-Rights Field. Protest Cycle and Networks of Catholic-Inspired Neoconservative Organisations (1978-2023)». Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 189: 63-92. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.189.63-92)

Joseba García Martín: Universidad del País Vasco | joseba.garciam@ehu.eus

Ignacia Perugorría: Universidad del País Vasco | ignacia.perugorria@ehu.eus

Several studies have addressed the mobilisation of Spanish far-right1 political organisations in recent years, both in their parliamentary and extra-parliamentary versions (Jiménez Aguilar and Álvarez-Benavides, 2023). These studies point to a growing institutionalisation (Romanos, Sádaba and Campillo, 2022), understood as “absorption”, of this protest since Vox gained institutional representation in 2018 (Rivera Otero, Castro Martínez and Mo Groba, 2021). However, at the time of finishing this article (November 2023), the demonstrations in front of the headquarters of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) against the investiture and amnesty pact between Pedro Sánchez’s government and the Catalan pro-independence parties have led us to qualify this diagnosis. So have the results discussed in this article, based on a systematic study of neo-conservative and Catholic-inspired civic organisations over more than four decades, some of which have promoted these very protests.

Our research has focused on the self-styled “pro-life” multi-organizational field (Klandermans, 1992), composed of what we have reconceptualised as “Catholic-inspired secular organisations of neo-conservative ideology” (CISO-Ns). This concept allows us to encompass all the anti-rights campaigns deployed by these organisations against morality politics (Euchner, 2019) legislated by progressive governments: laws on divorce, abortion, same-sex marriage, gender equality education, LGBTQ+ rights and euthanasia, to mention only the most controversial state-wide legislation. In Spain, the CISO-N field is made up of non-denominational civic organizations (Baldassarri and Diani, 2007) that deny having any organisational link to the Catholic Church. However, they are committed to defending life “from conception to natural death”2 by mobilising against such politics. These organisations are part of what we call “organised laity”, which emerged globally as a result of the Catholic Church’s strategic shift after the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) to develop a novel style of activism “outside the parishes” and beyond the channels of conservative political parties.

Spanish CISO-Ns fall within the framework of Catholic neo-conservatism, a political ideology that believes in the civic power of religion to organise society (Díaz-Salazar, 2007), and considers Catholicism as the only legitimate and desirable model of “national morality”, especially in matters related to private life. These organisations wage a battle in the cultural sphere (Hennig and Weiberg-Salzmann, 2021) based on the strategic secularisation (Vaggione, 2005) of discourses of moral and sex panic (Herdt, 2009) launched by the Church against the aforementioned morality politics (Dobbelaere and Pérez-Agote, 2015). This process involves “translating” Catholic discourse and reframing it within scientific and legal narratives for it to be subsequently transferred to the public sphere. CISO-Ns also mobilise politically to combat those legislative initiatives, political parties and social movements that go beyond or actively position themselves against the Catholic normative framework. To do so, they use the repertoires of protest (Tilly, 2012) that are typical of social movements. Thus, these multi-issue organisations (Aguilar Fernández, 2011) act on behalf of public and collective interests, and play a fundamental role in the construction of civil society (Diani, 2015) insofar as they contribute to political discussion, deliberation and mediation.

Our analysis aims to offer an alternative view to those interpretations (Kuhar and Paternotte, 2017) that have tended to identify the Catholic Church as the main “agent” behind this anti-rights battle. In these analyses the Church is presented as an omnipresent actor and top-down leader of CISO-Ns, while these organisations assume the role of mere “translators” and “conveyor belts” for its message. We also take issue with those studies (Mata, 2021) that have presented CISO-Ns as organisations “at the service” of conservative or far right political parties, providing votes, activists and, fundamentally, language and arguments for their opposition to the progressive agenda. In contrast, we argue that, over a cycle of protest (Della Porta, 2022) of more than four decades, CISO-Ns have become specialised, professionalised, and progressively independent from the logic of the Church and political parties to pursue a complex strategy of “repoliticisation of the religious” (Vaggione, 2014). While this strategy is clearly aligned with the Catholic canon and is obviously influenced by ties to political organisations, it is designed and implemented according to a logic specific to CISO-Ns which, as discussed below, takes into account central axes of social movement studies.

Our article analyses the mobilisation of the CISO-N field from its emergence in the context of the Spanish democratic Transition to the present day. We study this mobilisation from a relational and comparative-historical perspective. The relational perspective first considers the network structure and dynamics (Diani, 2003) of the CISO-N field and its inter-organisational ties to its expanded field. According to their principal areas of action, CISO-Ns can be organised into two main groups: those mobilising against morality politics (the core of our analysis); and sectoral bioethical, legal, educational, communication and welfare organisations. The expanded field is composed of ecclesiastical organisations, mainly the Spanish Episcopal Conference (CEE); and also of two types of political organisations: moderate and radical right-wing parties, such as the Popular Party (PP) and Vox, respectively, and the National Organisation of El Yunque3. All these civic, religious and political organisations seek to erode, curtail or curb self-determination in morality politics. They thus form what we call the “expanded anti-rights field”. Second, we study these fields as relational settings (Somers, 1994) formed by contested but relatively stable ties between these organisations, their identity discourses (Reger, Myers and Einwohner, 2008) and their repertoires of protest.

On the other hand, the comparative-historical approach simultaneously considers the cultural and political opportunity structures that affect the praxis of these organisations (Borland, 2014; Giugni et al., 2006; Goodwin and Jasper, 2012). We define “cultural opportunity structures” as having to do with two far-reaching processes: progressive religious change (Pérez-Agote, 2012) and the loss of the cultural hegemony of Catholicism both socially and politically since the late Francoist period (Ruiz Andrés, 2022); and the advance of the “politicisation of the private” led by the feminist and LGBTQ+ movements (Martínez, 2019) since the Spanish democratic Transition). Political opportunity structures, meanwhile, are linked to three shorter-term processes: the alternation between conservative and progressive governments; morality politics legislation; and the availability of allies in institutional politics. Bearing in mind this dual relational and comparative-historical perspective, our article aims to answer three main questions. First, what are the phases of the CISO-N field’s protest cycle from 1978 to the present, and how do they relate to changes in cultural and political opportunity structures? Second, how has the network structure and dynamics of the CISO-N field and its expanded anti-rights field evolved? And third, how do changes in opportunity structures and network structure influence both the discourses and repertoires of protest of the organisations studied?

Our study aims to make a threefold contribution to the literature on social movements and, more specifically, to the study of far-right Christian movements (Lo Mascolo, 2023). First, the Spanish CISO-N field has been studied primarily within the framework of the de-privatisation of religion (Cornejo-Valle and Pichardo-Galán, 2017; García Martín, 2022). And the few studies that have used a social movements perspective have mainly concentrated on mobilisation against sexual and reproductive rights (Aguilar Fernández, 2011) and so-called “anti-gender” (Cabezas, 2022) and anti-euthanasia (García Martín and Perugorría, 2023, 2024) protests. This research has focused on the last two decades and, for the most part, has dealt with these mobilisations in isolation. Our paper analyses the whole range of anti-rights campaigns over four decades (see Table A4), based on the understanding that they are interrelated manifestations of the “repoliticisation of the religious” strategy.

Second, our relational and comparative-historical approach allows us to undertake one of the first systematic analyses of the historical evolution of the field, connecting it to changing structures of cultural and political opportunity. This analysis identifies three phases in the CISO-N protest cycle, and also three consecutive network structures made up of civic, religious and political anti-rights organisations. This approach also makes it possible to recognise what we have called a “tactical-discursive cleavage” (García Martín and Perugorría, 2023) which, from 2009 onwards, fragmented the field into two cliques (Wasserman and Faust, 2013: 274) of organisations. On the one hand, those with a Catholic-conservative ideology, closer to the CEE; on the other hand, those more radicalised organisations linked to the far right represented by Vox and, in its most radical version, by the secret organisation El Yunque.

Third, the de-institutionalisation of the anti-rights struggle through civic organisations formally detached from the Catholic Church can also be observed in other European countries (Möser, Ramme and Takács, 2022; Lo Mascolo, 2023), and it resembles the “NGO-isation” strategy of Christian neo-conservative associations in Latin America (Morán Faúndes, 2023). However, Spain is a paradigmatic case for the study of the evolution of anti-rights protest for three reasons. First, the Spanish state is at the forefront in the recognition and regulation of morality politics worldwide (Griera, Martínez-Ariño and Clot-Garrell, 2021). Second, as shown by several comparative studies (Dobbelaere and Pérez-Agote, 2015; Kuhar and Paternotte, 2017), the Spanish CISO-N field is among the oldest, most mobilised and belligerent in Europe. Third, in recent decades the CISO-N field has become a clear reference point for the Latin American and European neoconservative fabric (Torres Santana, 2020). Thus, our study provides key insights to understand, and even foreshadow, the circulation of anti-rights strategies, discourses and repertoires well beyond Spain.

The article is organised as follows. It begins by describing our qualitative multi-method strategy and our fieldwork (2016-2023). This is followed by a brief description of the socio-historical context in which the Spanish CISO-N field emerged. The first analytical section focuses on the different phases of the protest cycle, relating them to changes in cultural and political opportunity structures. The second section discusses changes in the network structure and dynamics of the CISO-N field and the expanded anti-rights field. The discourses and repertoires of protest are addressed transversally in both sections.

The fieldwork for this qualitative multi-

methods study was divided into two phases (see Table A1 in the Appendix). During the first phase (2016-2020) the following were conducted: 1) in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of CISO-N activists4 (n=20; see Table A2); 2) participant observation of their demonstrations (n=4); and 3) an analysis of newspaper articles. Interviews were conducted in the cities of Bilbao, Pamplona and Madrid, where CISO-N recruitment and training networks are most extensive and effective. The sampling took into account two criteria: the organization to which the interviewee belonged, and his or her level of responsibility in it.

The netnographic fieldwork (Kozinetz, 2019) was carried out during our study’s second phase (2020-2023), largely coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. This covered the collection of public data from the Internet, organizations’ official websites, and their official accounts on YouTube and Twitter (currently, X). Netnography allowed for the study of a mobilisational field strongly based on cyberactivism, and helped us “overcome” the restrictions imposed by the lockdown and subsequent limitation in mobility. During both phases, secondary data such as Spanish legislation and the main government measures related to morality politics were also analysed (see Table A4).

All the organisations studied are shown in Table A3. A sub-sample of four CISO-Ns, selected for their centrality in the field during the period under analysis (1978-2023), is shown in Table A1. The table also includes the main anti-rights organisations of the expanded field: 1) the CEE, the highest authority of the Catholic Church in Spain; 2) PP and Vox, main political allies of the CISO-N field (particularly of their most radicalised organisations) after the distancing from the PP; and 3) El Yunque, an organisation that played a major role in the fragmentation of the field in 2009.

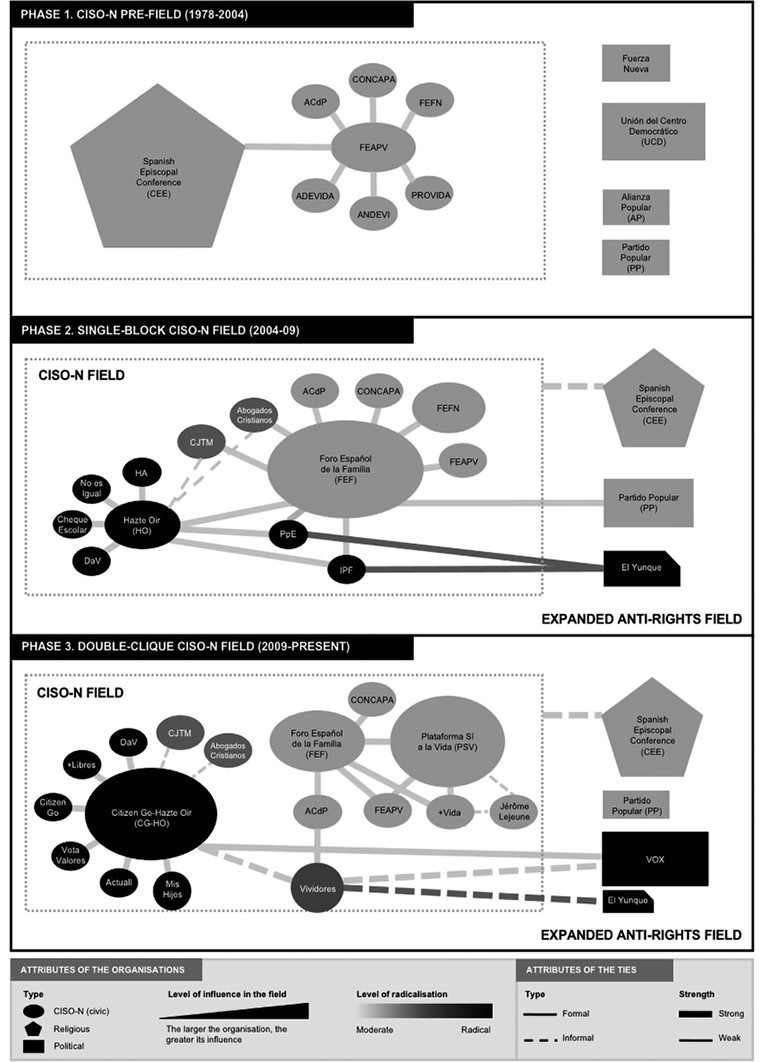

Data collected have been analysed following the principles of qualitative content analysis (Conde, 2009) and network analysis (Wasserman and Faust, 2013). The latter concentrates on the nodes (in our case, organisations), ties, and attributes of both. As can be seen in Figure 2, organisational attributes include: type of organisation (civic, religious or political); level of influence in the field; and level of radicalisation. Ties have two attributes, which have been dichotomised: type of link (formal/informal) and intensity (strong/weak). Following the terminology of the field (Wasserman and Faust, 2013), those nodes with a number of ties that greatly exceeds the average have been called hubs, and a cohesive group of nodes closely connected or “clustered” to each other (and not closely connected to organisations outside the group) have been called cliques.

Context of emergence and development of the ciso-n field: religious change and anti-rights struggle in Spain

During the four decades of Franco’s dictatorship (1939-1975) the Spanish Catholic Church played a prominent role in both the public and private spheres through “national-Catholicism”, a religious-political corpus that defended Catholicism as the ethno-religion of the Spanish nation (Botti, 1992). Francoism not only reinstated Catholicism as official state religion after the Republican “interregnum”, but also restored the Church’s monopoly over education and morality, driving an intense process of forced de-secularisation (Davie, 1999). Among other measures, this shift involved the annulment of civil marriages and divorces, the banning of contraception and the criminalisation of abortion (Callahan, 2012). Thus, the Francoist state deployed its coercive action to serve the ideal of the “Christian reconquest” and, in return, the Church functioned as the main legitimising agent of the dictatorship.

The symbiosis between the Church and Franco, however, began to erode in the mid-1960s. This was related, first, to the socio-economic, cultural and political opening that began during the late Franco era and led to the beginning of the so-called second wave (1960-2000) of the Spanish secularisation process (Pérez-Agote, 2012). During this wave, Spain underwent one of the most accelerated processes of religious change in the Western world, experiencing in a single generation “what in most of Europe has taken a century” (Davie, 1999: 78). As a result, Spain went from being “a Catholic country, governed by the Church, to being one with a Catholic culture, no longer governed by that Church” (Pérez-Agote, 2010: 51). Throughout this period, and despite the population’s still intense cultural identification with Catholicism (especially through rituals such as baptisms, first communions and marriages), indicators of religious practice fell and distrust of the Church increased (BBVA Foundation, 2022). Indifference to the Catholic doctrinal system also grew, particularly in relation to sexual and reproductive health, family models and, decades later, the use of biomedical technologies. Despite this growing gap between the institution and society, the Church maintained a privileged place in key sectors such as education, the military, and economic affairs thanks to the 1979 Concordat, signed during the democratic Transition (Callahan, 2012).

Second, due to the imposition of religion and the decades of isolationism during Franco’s regime, this secularising wave had arrived in Spain with considerable delay. However, it was already widely established in other European countries (Berger, Davie and Fokas, 2008). In an attempt to contain its expansion, in the early 1960s the Vatican spearheaded an aggiornamento and a global strategic shift in order to defend its position in the public sphere (Casanova, 2000). Designed at the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965), this shift was based, on the one hand, on a commitment to non-interference in the political life of states, either through direct participation in government (as had been the case during the dictatorship), or through support for certain political parties. On the other hand, it relied on the growing empowerment of the laity, composed of citizen believers (Gamper, 2010), as the new political agent and “representative” of ecclesiastical interests in the public sphere. In Spain, this shift had two main consequences. First, ecclesiastical support for Francoism was withdrawn and statements were made in favour of democratic pluralism (Piñol, 1999). Second, an “organisational explosion” of CISO-Ns in the context of modernisation triggered by the Transition (see Figure 1 and Table A3). This process launched a new style of activism based on the combination of social movement repertoires and the strategic secularisation of ecclesiastical discourse5. We have labelled this as “organised laity”.

Finally, the third wave of the Spanish secularisation process (2000-present) would arrive twenty years later, deepening the trends from the previous stage, and eroding part of Catholicism’s cultural capital (Astor, Burchardt and Griera, 2017 ). This marked the beginning of the process of exculturation (Pérez-Agote, 2012), mainly associated with the growing support for the secularisation of conscience and a continued decline in intra-familial religious transmission (Rossi and Scappini, 2016). Especially strong among youth, these trends explain the declining recruitment levels and waning resonance of the CISO-N message in recent decades, and, ultimately, the widespread social acceptance of progressive morality politics. These trends coincide with a context of increasing mainstreaming of feminist and LGBTQ+ postulates, which pursue a strategy based on the “politicisation of the private”, radically opposed to that proposed by CISO-Ns.

Morality politics legislation and ciso-n protest cycles: from ideological to affective polarisation

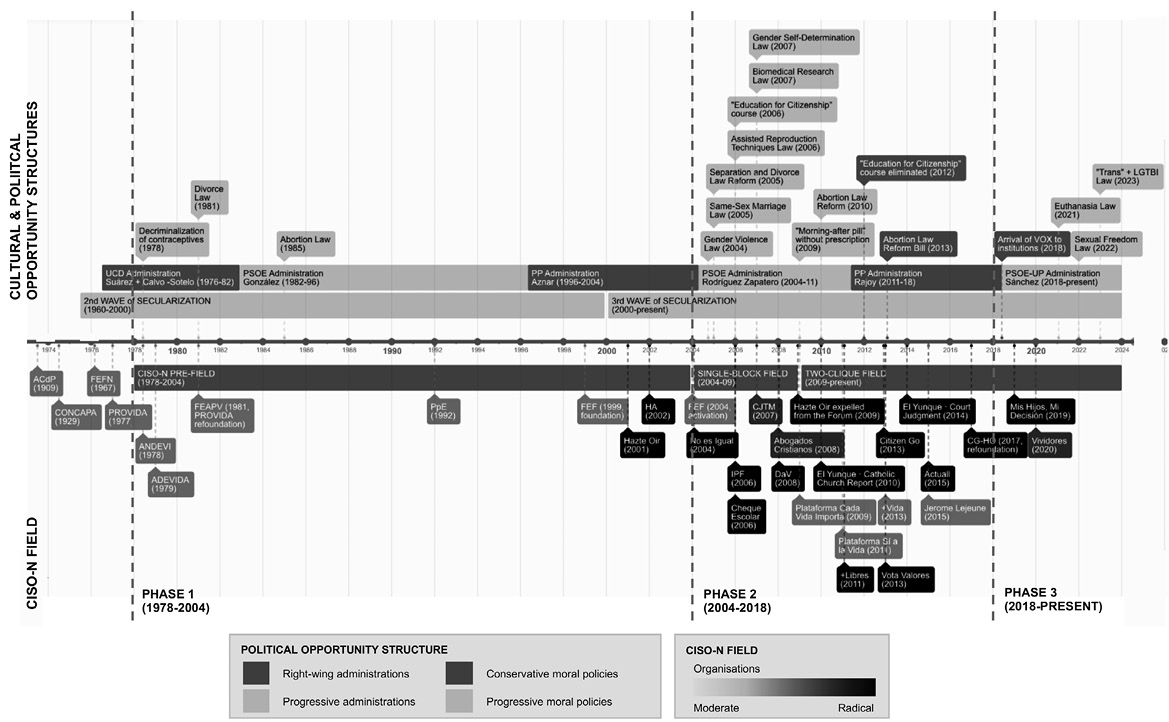

From 1978 onwards, the CISO-N protests cycle could be divided into three main phases (see Figure 1). Each of these began with a peak in mobilisation, generally associated with the introduction of bills contrary to the Catholic doctrine (see Table A4), and ended with a second sub-phase of gradual disengagement after these laws were passed. The first phase (1978-2004) coincided with a field that was still unstructured and highly influenced by the CEE, what we will call the “pre-field” in the next section. This phase encompassed mobilisations to combat the decriminalisation of the sale, distribution and use of contraceptives (1978) and the Divorce Law (1981), measures demanded by the nascent feminist movement. These laws were adopted during the governments of the Union of the Democratic Centre (UCD), heir to reformist Francoists with strong ties to the CEE (Callahan, 2012). Although the UCD was the a priori “natural ally” of CISO-Ns, the party led the process of modernisation that began after the dictatorship, and took the first steps in legislating legislating on progressive morality politics (see Figure 1 and Table A4).

The main anti-rights campaign of this first phase would come four years later, with the opposition to the Abortion Law (1985) promoted by Felipe González’s PSOE. Since then, the PSOE has been the main proponent of these policies, and is consequently identified as the field’s main enemy. The fight against abortion galvanised the CISO-N field and gave it visibility in the public space. As can be seen in Image 1, during this campaign CISO-Ns organised conventional protest events (Carvalho, 2024) (demonstrations, mainly in Madrid) and more disruptive events such as sidewalk counselling in front of abortion clinics. Despite this strong mobilisation, the precarious articulation of the field, the lack of institutional political support due to the UCD’s democratising impetus, and the waning commitment of activists (except for the generations socialised during Franco’s regime) led to the failure of the anti-abortion campaign. From the late 1980s onwards, the field showed signs of weakening and began to retreat into its religious base. This support focused mainly on assisting pregnant women and families in precarious situations in order to “curb” the number of abortions.

This retreat sub-phase ended in 2004, when Rodríguez Zapatero’s PSOE (2004-2011) came to power with the promise of expanding divorce and abortion laws and of legislating the right to same-sex marriage (Cornejo-Valle and Pichardo-Galán, 2017). This gave birth to the second phase of the CISO-N protest cycle (2004-2018), which coincided with the beginning of the third wave of secularisation (2000-present). As will be discussed in the next section, the intense anti-rights mobilisation that characterised this phase was led by the Spanish Family Forum (Foro Español de la Familia, FEF). This organisation united the field and renewed the unsuccessful discursive frames (Benford and Snow, 2000) that had been constructed during the previous phase of the protest cycle. These had been strongly confrontational in tone (equating divorce with “social disorder” and “destruction of the family”, and abortion with “murder”), aimed at causing a moral panic in society. Instead, the FEF proposed more “moderate” and “conciliatory” frameworks, aligned with the shifting strategy of the US “pro-life” movement (Munson, 2010). Among them were the valuing of the heteronormative family, the defence of life in all its stages, intergenerational dialogue, and the joy associated with motherhood. These frames were reflected in slogans such as “Family matters” against equal marriage (see Figure 2) and “Sexuality does matter, no doubt about it” against the creation of sex education modules in schools (a slogan which in the original Spanish La sexualidad sí importa, sin ningún género de duda included a reference to sexual-affective education, branded by the FEF as “indoctrination”). The FEF’s repertoires included conventional protest events (e.g. demonstrations, street-poster campaigns, sit-ins in front of government buildings), and a strong presence in the conservative and Catholic media. This mobilising strategy sought to cause ideological polarisation (Freidin, Moro and Silenzi, 2022), both tactically and discursively. However, during this phase, newer repertoires also emerged, such as performances and the incipient use of the internet and social media. Mostly led by Citizen Go-Make Yourself Heard (Citizen Go-Hazte Oir, CG-HO)6,—member of the FEF until it was expelled in 2009—these protest events had a more belligerent tone, which “sabotaged” the FEF’s “inclusive” strategy. Despite this fierce opposition, the PSOE managed to pass a total of nine progressive morality politics laws in eight years (see Figure 1 and Table A4), earning the characterisation of “most confrontational administration” with the CISO-N cause in Spain’s democratic history (Arsuaga and Vidal Santos, 2010).

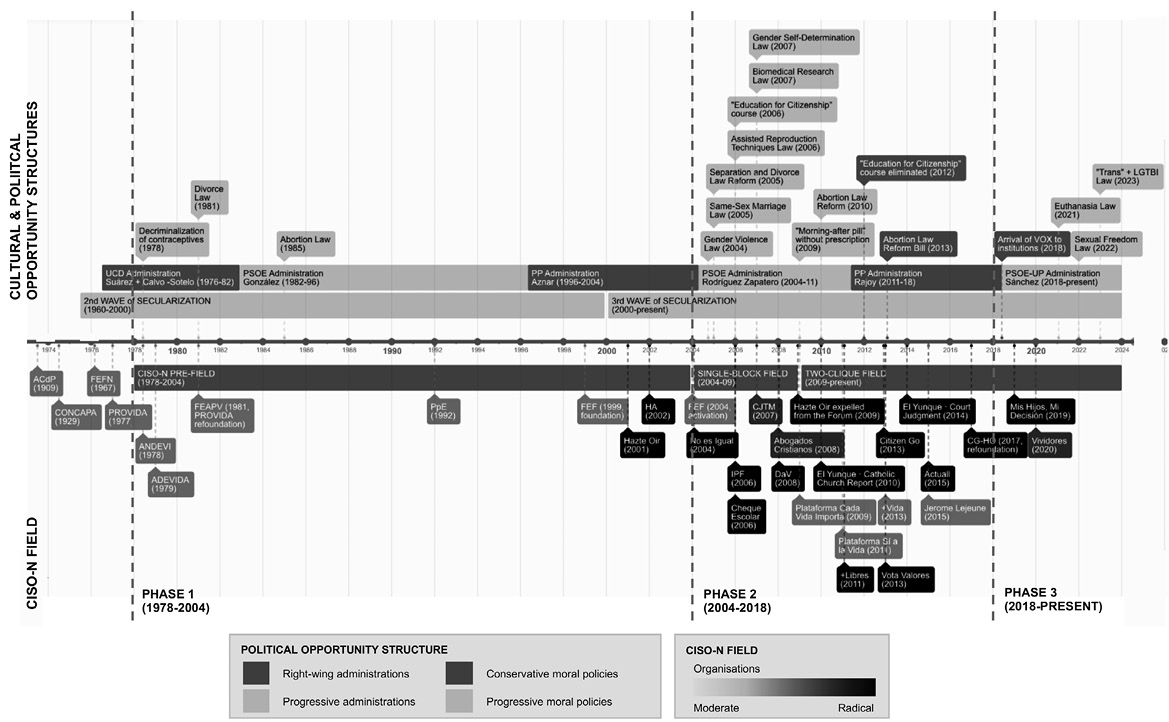

Two years later, a new sub-phase of retreat began with the arrival of Mariano Rajoy’s PP in government (2012-18). Against all odds, once in office the PP neither modified nor repealed the PSOE’s morality politic PSOE’s morality politics laws, all of which had been strongly contested by the CISO-N field and the PP itself from the opposition. In fact, in 2014 the PP withdrew a reggressive reform project of Rodríguez Zapatero’s Abortion Law brought forward by its own Minister of Justice, Alberto Ruiz Gallardón (see Table A4). The PP’s veto of this project put an end to the formal tie between the FEF and the party, and triggered Ruiz Gallardón’s resignation. In this context, the FEF returned to welfare and educational activities in the areas of family and sexuality, and allocated both financial and human resources to supporting the annual International Day of Life demonstration, organised since 2011 by the Yes to Life Platform (Plataforma Sí a la Vida, PSV). In the meantime, after CG-HO was expelled from the FEF, it turned to cyber-activism, combining its anti-rights struggle with increasingly “purely” political mobilisation. This struggle is led primarily by its lobby group Vote Values (Vota Valores), explicitly dedicated to “effectively influencing politicians in defence of life, family and liberty” (VotaValores.org). As shown in Figure 3, since 2013, this platform has campaigned both online and in the public space, and has published its famous “voting guides” for the general and regional elections. These guides “grade” parties on the basis of their more or less conservative stances towards morality politics legislation.

The beginning of the third phase (2018-present) of the CISO-N protest cycle was marked by three events. The first was the incorporation of the progressive coalition PSOE-Together We Can (PSOE-Unidas Podemos, PSOE-UP) into Spain’s Presidency, with UP representatives close to the feminist and LGBTQ+ movements in key positions, such as the Ministry of Equality. This triggered numerous “anti-gender” mobilisations (Cabezas, 2022), especially led by CG-HO, which sought to directly antagonise feminism and the coalition government. The second event was the landing of the far-right Vox party in both the Spanish Congress and in several regional parliaments7. From then on, Vox replaced the PP as the “natural ally” of CISO-Ns, and as the “conveyor belt” for their message to institutional politics. This was an important milestone in the CISO-Ns’ protest cycle, as it was the first time that the field had had a “reliable” ally in institutional politics that amplified its discourse beyond protests in the public space, and tried to translate its ideas into political proposals.

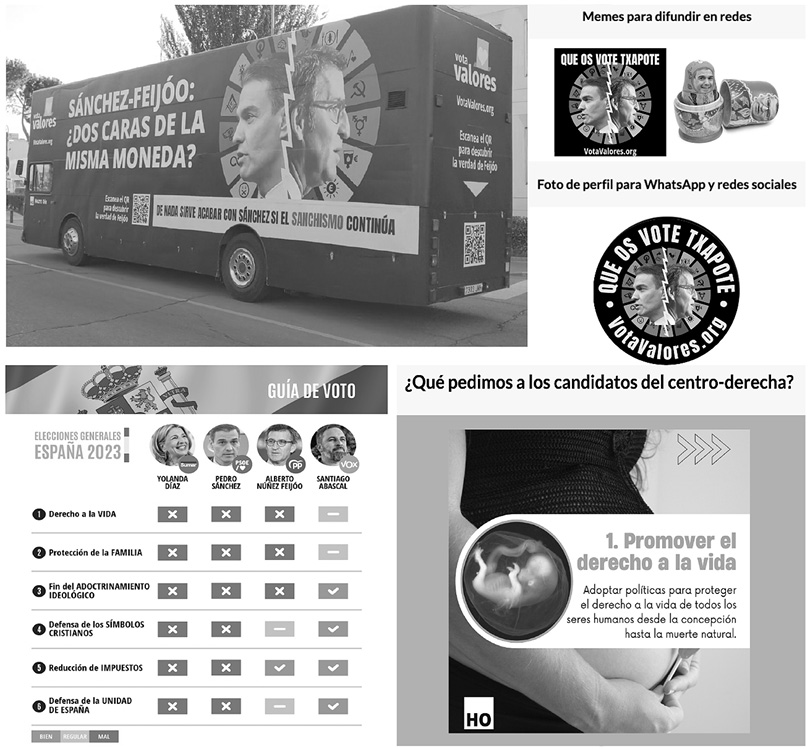

The third process that marked the last phase of the CISO-N protest cycle was the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the parliamentary debate on the Euthanasia Bill (2021) was revived. Faced with COVID-related high mortality rates in nursing homes, Vox adopted the discursive frameworks developed by a CISO-N called Vividores (the first specifically anti-euthanasia organisation in the field) began a strong anti-government campaign (García Martín and Perugorría, 2024). As we will explain in the next section, the “clustering” of the field produced during the previous phase was already well established, and was expressed in a tactical-discursive cleavage in mobilisation (García Martín and Perugorría, 2023). Born from the heart of the FEF-related Catholic Association of Propagandists (Asociación Católica de Propagandistas (ACdP)), Vividores transcended this cleavage for the first time and, as can be seen in Image 4, quickly evolved towards frameworks and repertoires that replicated those of CG-HO. These followed a friend/foe logic that went beyond the ideological polarisation typically deployed by the FEF, based on divergence of beliefs and opinions. Instead, CG-HO, Vox and related organisations fostered affective polarisation8 (Freidin, Moro and Silenzi, 2022) by mobilising “negative” emotions (intolerance, dislike and hostility) to divide the actors involved into antagonistic fields, stigmatise adversaries, and “expell” them from the democratic debate.

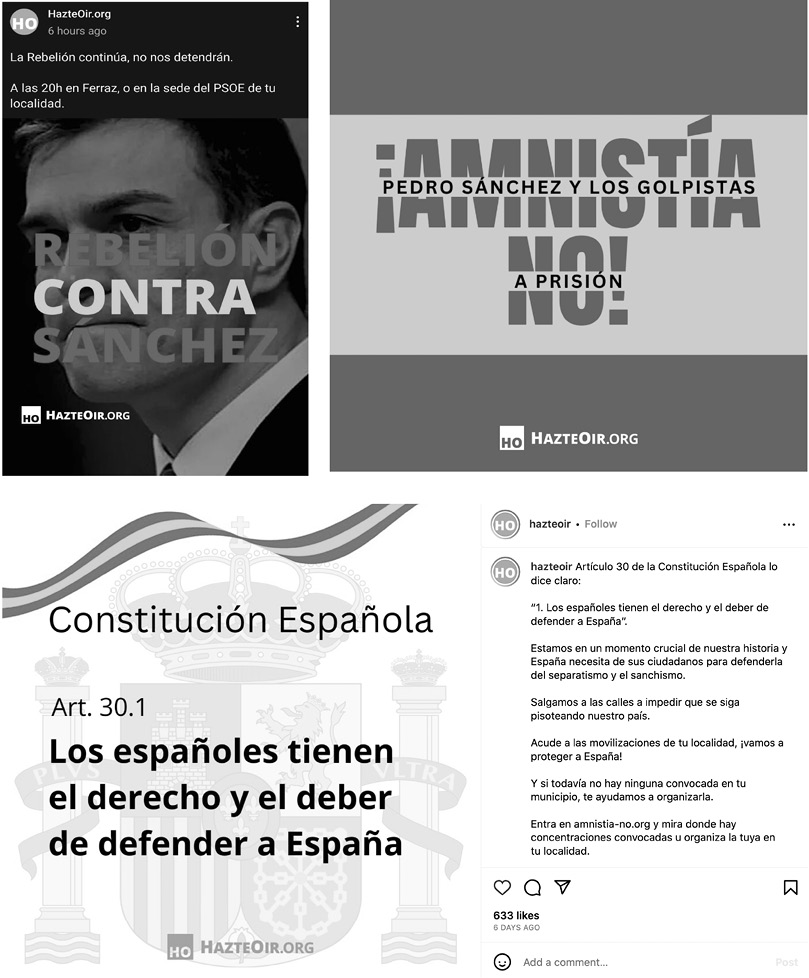

Despite this, the Euthanasia Law was passed in 2021, and was then followed by the Sexual Freedom Law (Ley de “Solo Sí es Sí”, 2022) and the so-called Trans Law (2023) (see Figure 1 and Table A4). These last two laws once again, positioned the “anti-gender” struggle, as one of the main axes of CISO-N protest today. In the current sub-phase of retreat, CG-HO has embarked on an attrition and discrediting campaign against the Sánchez administration. This reached its peak in November 2023, with the fierce opposition to the investiture and amnesty pact between the PSOE and the Catalan independence movement (see Image 5) under the slogan “Let Txapote vote for you” (Que te vote Txapote). This “purely political” drift in defence of the Constitution and the unity of Spain, completely detached from morality politics, seems to be deepening in the case of CG-HO, further distinguishing it from organisations close to the FEF.

Network structure and dynamics of the ciso-n field and the expanded anti-rights field: from a common front to “clustering”

In the previous section we focused on our study’s comparative-historical approach describing the different phases of the CISO-N field’s protest cycle and its interaction with cultural and political opportunity structures. By relying on our relational perspective, this section will show the evolution of the network structure and dynamics of the CISO-N field and its expanded field. In line with this approach, the CISO-N field is understood not as an “aggregation of organisations”, but as a:

Relational arena characterised by mutual orientation, positioning, and (at times) joint action among multiple kinds of actors engaged in diverse forms of collective intervention and challenge (Diani and Mische, 2015: 307).

In turn, this perspective looks at the contested but relatively stable ties between organisations (Diani and McAdam, 2003), identity discourses and protest repertoires, all of which are largely influenced by the opportunity structures discussed in the previous section.

Figure 2 presents snapshots of the evolving structure of the CISO-N and the expanded anti-rights fields in three consecutive phases. The snapshot of the first phase (1978-1989) shows a “pre-field” made up of young, uncoordinated organisations with little visibility and influence beyond the confines of the Catholic community. These organisations were under the strong influence of the CEE (this phase’s hub), both discursively and organisationally. Consequently, it can be stated that the “externalisation of political action” through the protest of the laity organised in CISO-Ns was a strategy to circumvent the principle of non-interference in politics established by the Second Vatican Council.

The most relevant CISO-N during this phase was the Spanish Federation of Pro-Life Associations (Federación Española de Asociaciones Provida, FEAPV), which emerged in 1981 and brought together different organisations that primarily engaged in welfare activities. Although this organisation is still active today as the driving force behind the PSV, it retains symbolic capital, but has lost all real power. As mentioned in the first section, the intense process of political change during this first phase, in addition to the alternation between conservative and progressive governments, meant that the CISO-N field had no stable allies in institutional politics. The UCD promoted and supported legislation that was totally opposed to CISO-N demands (see Figure 1 and Table A4), and Alianza Popular (AP) and later on the PP operated along the same lines. Both parties aligned themselves with CISO-Ns while in the opposition, but once in office they neither amended nor repealed the laws passed by the socialist governments that preceded them, ignoring strong pressure from their own Christian-Democratic sectors.

The snapshot of the second phase (1999-2009) shows a real CISO-N field articulated and differentiated from the CEE, composed of organisations that began to wage the anti-rights struggle on their own terms, i.e. according to their own interpretation of opportunity structures, pursuing their own objectives and activating other kinds of ties. During this period, the field operated as a united front under the leadership of the FEF, a network of associations founded in 1999 by activists close to Opus Dei and with strong informal ties to the CEE. The FEF remained dormant until 2004, when it became active to lead the mobilisation against same-sex marriage legislation promoted by Rodríguez Zapatero’s PSOE government. During this phase, the FEF operated as a single hub and achieved the greatest organisational coherence and density of the CISO-N field since the early 1980s. It severed formal ties to the CEE and advanced the strategic secularisation of its discourse (García Martín, 2022) with respect to that used in the first phase. In doing so, it supplanted the Catholic Church as political contender (Aguilar Fernández, 2011), defending “social order” and the Christian conception of the person through mobilisation in the public space. Since then, the link between CISO-Ns and the CEE has been informal, and the CEE has limited itself to publishing documents that build the argumentative umbrella of the anti-rights battle, replicating those issued by the Vatican (Cornejo-Valle and Pichardo-Galán, 2020). During this phase, the FEF maintained a strong formal link with the PP, the main opposition to the PSOE government. This was due to the identification of a “common enemy”, as well as to the strong ties between the PP and Benigno Blanco, a supernumerary member of Opus Dei, president of the FEF between 2007-2015, and PP’s former secretary of state during the governments of José M.ª Aznar (1996-2004). Although it would later prove to be an unreliable ally, during this period the PP functioned as a “conveyor belt” for CISO-N discourse in the institutional political sphere, used to oppose Rodríguez Zapatero’s socialist government.

Finally, the snapshot of the third phase (2009-present) shows a field with three large hubs (CG-HO, PSV and the FEF) that is highly clustered into two cliques: the first composed of CG-HO and all its platforms, and the second one made up by the FEF, PSV and their related organisations. This clustering, still present today, took place in the heat of the debates on Rodríguez Zapatero’s reform of the Abortion Law, which was finally approved in 2010. The failure of the FEF’s anti-abortion strategy generated growing discontent among the most radicalised sectors of the field led by CG-HO, an organisation strongly influenced by US “pro-life” groups and Spain’s most internationalised CISO-N. As mentioned, when in 2009 Benigno Blanco, leader of the FEF, internally denounced that El Yunque was “nested” in CG-HO (a fact that was later confirmed in court), the latter and all its sectoral organisations were expelled from the FEF and from several dioceses (Mata, 2015). Despite its ultra-Catholic rhetoric, El Yunque was identified as a secret organisation with its own agenda, and had a parasitic relationship with the structures of the CISO-N field and the CEE to recruit followers to its cause. The expulsion of CG-HO made it clear that, despite their supposed non-confessional status and dissociation from the CEE, CISO-Ns in the moderate clique close ranks around the Catholic Church when the institution is under threat. Behind the expulsion was also a growing rivalry for prominence in the public space between the FEF and CG-HO, as well as tensions arising from the increasing belligerence of CG-HO’s discourse and repertoire, in clear contradiction to the FEF’s more conciliatory strategy.

Faced with a worn-out FEF in open confrontation with CG-HO, the need arose to create a new organisation that could re-agglutinate the field and, simultaneously, curb the expansion of CG-HO. This organisation was the PSV, founded in 2009, led by the FEAPV (the organisation that initiated the cycle of protest during the Transition), and fully supported by the FEF and its related organisations. Since then, PSV’s only activity has been the mobilisation to commemorate the International Day of Life (25 March) in opposition to the Abortion and Euthanasia Laws. Since its expulsion from the FEF, CG-HO has duplicated the structure of the CISO-N field by creating a rhizome of sectoral platforms which, in addition to giving it a presence in all areas of the anti-rights struggle (see Table A4), has concealed its isolation from the “moderate” clique (see Figure 2). Together with its growing cyberactivism, political lobbying and internationalisation, this strategy has strengthened CG-HO to the point where it is now the most powerful and visible CISO-N in the field.

At the same time, in this phase CG-HO began its first contacts with the “prehistory” of Vox (2013). These ties intensified when PP leader Mariano Rajoy became President of Spain (2012-2018) and, once again, did neither modified nor repealed the battery of laws passed by the socialist government during the previous years. While this definitely eroded the formal link between the field and the party, some informal ties between activists and sympathisers remain today. As has been mentioned, in the following years, and especially since its arrival in the institutions in 2018, Vox replaced the PP as the main ally of CISO-Ns, especially of CG-HO, amplifying its discourse in the public sphere and in institutional politics (due to the presence of El Yunque also in Vox, this alliance has been more problematic for the “moderate” clique). In return, CG-HO promotes the party as the only one defending the field’s values through its “voting guides” (see Figure 3), and also functions as a “referential network” for Vox militants. In fact, there have often been synchronised campaigns and jointly organised protest events between both organisations (García Martín and Perugorría, 2023), and many of their members have double militancies in both CG-HO and Vox (Mata, 2021). As has been mentioned, CG-HO has turned towards a purely political mobilisation against the Sánchez administration, adopting a highly belligerent tone that is very much in line with Vox’s style.

It is undeniable that the CISO-N field as a whole has multiple intersections in terms of funding sources and information dissemination networks, as well as the issues around which it is mobilised. However, in the current third phase the cliques operate independently, and deploy different strategies to wage the cultural battle and political mobilisation against progressive morality politics. Likewise, as we showed in the previous section, they differ in their choice of protest repertoires and in the level of drama and belligerence of their discourse. In this sense, we can speak of a tactical-discursive cleavage between the organisations into a more “moderate” clique (led by the FEF and PSV) linked to Catholic conservatism and close to the CEE, and a more radical one (CG-HO and its platforms) linked to the political far right. There is currently no communication or formal ties between these cliques (not even through Vividores, which was born from the FEF and ended up orbiting towards CG-HO), but there exists rather a cordon sanitaire to try to prevent CG-HO from co-opting FEF and PSV members. Although this clustering has taken place at the organisational level, as we observed in the CISO-N anti-euthanasia campaign (García Martín and Perugorría, 2023, 2024), ties and communications have been more fluid at the level of activists and protest events.

This article has analysed the mobilisation of the Spanish CISO-N field from its emergence amidst the democratic Transition to the present day. The historical-comparative perspective has made it possible to identify three phases within its four-decade protest cycle, and to relate them to changes in the cultural and political opportunity structures. In parallel, thanks to the relational perspective, we have been able to distinguish three consecutive network structures of the CISO-N and its expanded fields, and we have traced the evolution of the contested but relatively stable ties between their organisations, discourses and protest repertoires.

As mentioned, Spain is at the international forefront in the recognition of rights related to sexual and reproductive health, gender equality and end-of-life process. Likewise, the Spanish CISO-N field is a point of reference in both Europe and Latin America. For these reasons, our study provides keys to understanding, and probably foreshadowing, the circulation of strategies, discourses and repertoires of what we have called the organised laity beyond the confines of the Spanish state. Furthermore, by focusing on a novel style of activism “outside the parishes” and beyond the channels of conservative political parties, our research makes four contributions to the literature on social movements and, more specifically, to the study of far-right Christian movements.

First, our study identifies stable organisational networks that are activated in the face of progressive morality politics legislation related to private life. These legal provisions go far beyond legislation on the right to abortion and euthanasia (aligned with the motto of “defending life from conception to natural death”), and even the rights of the LGBTQ+ community. Hence the dual need to discard self-granted terms such as “pro-life”, and to revise academic concepts such as “anti-gender”, replacing them with the broader notion of “anti-rights organisations”. The latter has the benefit of encompassing all the campaigns in which CISO-N networks have mobilised from the 1970s to the present day. Our work combines this reconceptualising impetus with an effort to provide empirical “granularity” and analytical depth, highlighting the field’s growing organisational and tactical-discursive complexity, so far obscured by predominantly monolithic representations.

Second, our study allows us to dispute those interpretations that see the Catholic Church as the main “agent” behind anti-rights campaigns. These studies tend to overemphasise both the role of ordained members and the impact of Vatican and CEE documents on the field. As a consequence, CISO-Ns are reduced to the role of mere “translators” and “conveyor belts” for the Church’s message. While this interpretation may have been appropriate for the first phase of the CISO-N protest cycle, our data paint a very different picture from 2004 onwards. The same applies to the relationship between CISO-Ns and political parties. While the relationship with the PP during the second phase of the cycle may have been “parasitic” in nature, the link to Vox seems to be of a more “symbiotic” type so far.

Third, our study identifies CISO-N organisational networks that expand over forty years, retreating into welfarism, political lobbying and cyberactivism in periods of mobilisational decline, and (re)surfacing in the public space in sub-phases of parliamentary morality politics debate. This fact allows us to affirm that, these campaigns are interrelated manifestations of a far-reaching strategy which, pursues an ambitious strategic objective: the re-politicisation of the religious. This strategy has been adapted not only to political opportunity structures, but also to changes in cultural opportunities. In this sense, Spanish CISO-Ns are fighting their anti-rights battle in a context of growing secularisation and erosion of the cultural hegemony of Catholicism, and in the face of an important “politicisation of the private” linked to the growing transversalisation of feminist and LGBTQ+ postulates.

Finally, our analysis of CISO-N organisations complements and qualifies the results of studies that have focused solely on far-right political organisations. Our results indicate the persistence of non-institutionalised protests, led by neo-conservative civic organisations that have not been absorbed by Vox. Rather, what we observe is a growing specialisation and strategic triangulation between civic, religious and political organisations that make up what we have called the expanded anti-rights field, and, secondly, a profound clustering of CISO-Ns that is expressed in a tactical-discursive cleavage. While the Catholic conservative clique close to the CEE, deploys “moderate” and conciliatory discourses and repertoires that seek ideological polarisation, CG-HO and its satellite platforms identify as “soldiers fighting the culture war” and contributing to a context of growing affective polarisation. It is this latter clique which, together with Vox and other political organisations of the extra-parliamentary far right, promoted the recent protests against the investiture and amnesty pact between the Catalan pro-independence movement and Pedro Sánchez’s PSOE government.

Aguilar Fernández, Susana (2011). “El movimiento antiabortista en la España del siglo XXI: El protagonismo de los grupos laicos cristianos y su alianza de facto con la Iglesia católica”. Revista de Estudios Políticos, 154: 11-39.

Arsuaga, Ignacio and Vidal Santos, Miguel (2010). Proyecto Zapatero. Madrid: HazteOír.org.

Astor, Avi; Burchardt, Marian and Griera, Mar (2017). “The Politics of Religious Heritage: Framing Claims to Religion as Culture in Spain”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 56(1): 126-142.

Baldassarri, Delia and Diani, Mario (2007). “The Integrative Power of Civic Networks”. American Journal of Sociology, 113(3): 735-780. doi: 10.1086/521839

Benford, Robert D. and Snow, David A. (2000). “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment”. Annual Review of Sociology, 26: 611-639. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/223459

Berger, Peter L.; Davie, Grace and Fokas, Effie (2008). Religious America, Secular Europe? Hampshire: Ashgate.

Borland, Elizabeth (2014). “Storytelling, Identity, and Strategy: Perceiving Shifting Obstacles in the Fight for Abortion Rights in Argentina”. Sociological Perspectives, 57(4): 488-505. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44290110

Botti, Alfonso (1992). Cielo y dinero. Madrid: Alianza.

Cabezas, Marta (2022). “Silencing Feminism? Gender and the Rise of the Nationalist Far Right in Spain”. Signs, 47(2): 319-345. doi: 10.1086/716858

Callahan, William J. (2012). La Iglesia católica en España. Barcelona: Crítica.

Carvalho, Tiago (2024). Analysing Protest Events: a Quantitative and Systematic Approach. In: Arribas Lozano, A.; Szolucha, A.; Cox, L. and Chattopadhyay, S. (eds.). Handbook of Research Methods and Applications for Social Movements (pp. 257-270). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Casanova, José (2000). Religiones públicas en el mundo moderno. Madrid: PPC.

Conde, Fernando (2009). Análisis sociológico del sistema de discursos. Madrid: CIS.

Cornejo-Valle, Mónica and Pichardo-Galán, José Ignacio (2017). From the Pulpit to the Streets. In: Kuhar, R. and Paternotte, D. (eds.). Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe (pp. 233-251). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Cornejo-Valle, Mónica and Pichardo-Galan, José Ignacio (2020). The Ultraconservative Agenda Against Sexual Rights in Spain: A Catholic Repertoire of Contention to Reframe Public Concerns. In: Derks, M. and Berg, M. van den (eds.). Public Discourses About Homosexuality and Religion in Europe and Beyond (pp. 219-239). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Davie, Grace (1999). Europe: The Exception That Proves the Rule? In: P. L. Berger (ed.). The Desecularization of the World (pp. 65-84). Washington: EPPC.

Della Porta, Donatella (2022). Protest Cycles and Waves. In: Snow, D. A.; Della Porta, D. and McAdam, D. (eds.). The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements (pp. 1-8). Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

Diani, Mario (2015). The Cement of Civil Society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Diani, Mario and Mische, Ann (2015). Network Approaches and Social Movements. In: Della Porta, D. and Diani, M. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Social Movements (pp. 306-325). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Díaz-Salazar, Rafael (2007). Democracia laica y religión pública. Madrid: Taurus.

Dobbelaere, Karel and Pérez-Agote, Alfonso (eds.) (2015). The Intimate. Leuven: LUP.

Estruch, Joan (1993). Santos y pillos. Barcelona: Herder.

Euchner, Eva-Maria (2019). Morality Politics in a Secular Age. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Freidin, Esteban; Moro, Rodrigo and Silenzi, María Inés (2022). “El estudio de la polarización afectiva: Una mirada metodológica”. Sociedad Argentina de Análisis Político, 16(1): 37-63. doi: 10.46468/rsaap.16.1.A2

Fundación BBVA (2022). Confianza en la Sociedad Española. Madrid: BBVA.

Gamper, Daniel (2010). Ciudadanos creyentes: el encaje democrático de la religión. In: Camps, V. (ed.). Democracia sin ciudadanos (pp. 115-138). Madrid: Trotta.

García Martín, Joseba (2022). “Desprivatización católica, políticas morales y asociacionismo neoconservador: el caso de los grupos laicos de inspiración cristiana en el Estado español”. Papeles del CEIC, 259: 1-19. doi: 10.1387/pceic.22973

García Martín, Joseba and Perugorría, Ignacia (2023). “El campo antiderechos español frente a la Ley de Eutanasia. Repertorio movilizacional y trabajo identitario (2018-21)”. Revista Internacional de Sociología, 81(4): e238. doi: 10.3989/ris.2022.81.4.1143

García Martín, Joseba and Perugorría, Ignacia (2024): “Fighting Against Assisted Dying in Spain: Catholic-Inspired Civic Mobilization During the COVID-19 Pandemic”. Politics and Religion, 17(2): 1-26. doi:10.1017/S1755048324000051.

Giugni, Marco; Koopmans, Ruud; Passy, Florence and Statham, Paul (2006). “Institutional and Discursive Opportunities for Extreme-Right Mobilization in Five Countries”. Mobilization, 10(1): 145-162. doi: 10.17813/maiq.10.1.n40611874k23l1v7

Goodwin, Jeff and Jasper, James M. (eds.) (2012). Contention in Context. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Griera, Mar; Martínez-Ariño, Julia and Clot-Garrell, Anna (2021). “Banal Catholicism, Morality Policies and the Politics of Belonging in Spain”. Religions, 12(5): 293. doi: 10.3390/rel12050293

Hennig, Anja and Weiberg-Salzmann, Miriam (eds.) (2021). Illiberal Politics and Religion in Europe and Beyond. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Herdt, Gilbert (2009). Moral Panics, Sex Panics. New York: New York University Press.

Ignazi, Piero (2003). Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jiménez Aguilar, Francisco and Álvarez-Benavides, Antonio (2023). “The New Spanish Far-Right Movement: Crisis, National Priority and Ultranationalist Charity”. Nations and Nationalism, pp. 1-17. doi: 10.1111/nana.12992

Klandermans, Bert (1992). The Social Construction of Protest and Multiorganizational Fields. In: A. Morris and C. McClurg Mueller (eds.). Frontiers in Social Movements (pp. 77-103). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kozinetz, Robert V. (2019). Netnography. London: SAGE.

Kuhar, Roman and Paternotte, David (eds.) (2017). Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Lo Mascolo, Gionathan (ed.) (2023). The Christian Right in Europe. Berlin: Transcript Verlag.

Martínez, María (2019). Identidades en proceso. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Mata, Santiago (2015). El Yunque en España. Madrid: Amanecer.

Mata, Santiago (2021). Vox y El Yunque. Madrid: Amanecer.

Morán Faúndes, José Manuel (2023). “La configuración de agrupaciones civiles neoconservadoras en Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador y Perú: una caracterización del activismo neoconservador en la subregión Andina”. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Género de El Colegio de México, 9: e967. doi: 10.24201/reg.v9i1.967

Möser, Cornelia; Ramme, Jennifer and Takács, Judit (eds.) (2022). Paradoxical Right-Wing Sexual Politics in Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Munson, Ziad (2010). The Making of Pro-Life Activists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Pérez-Agote, Alfonso (2010). “La irreligión de la juventud española”. Revista de Estudios de Juventud, 91: 49-63.

Pérez-Agote, Alfonso (2012). Cambio religioso en España. Madrid: CIS.

Piñol, Josep Mª. (1999). La transición democrática de la Iglesia católica española. Madrid: Trotta.

Reger, Jo; Myers, Daniel J. and Einwohner, Rachel L. (eds.) (2008). Identity Work in Social Movements. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Rivera Otero, José Manuel; Castro Martínez, Paloma and Mo Groba, Diego (2021). “Emociones y extrema derecha: el caso de VOX en Andalucía”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 176: 119-140. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.176.119

Romanos, Eduardo; Sádaba, Igor and Campillo, Inés (2022). “La protesta en tiempos de COVID”. Revista Española de Sociología, 31(4): a140. doi: 10.22325/fes/res.2022.140.

Rossi, Maurizio and Scappini, Ettore (2016). “The Dynamics of Religious Practice in Spain from the Mid-19th Century to 2010”. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 55(3): 579-596. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26651598

Ruiz Andrés, Rafael (2022). La secularización en España. Madrid: Cátedra.

Somers, Margaret R. (1994). “The Narrative Constitution of Identity: A Relational and Network Approach”. Theory and Society, 23(5): 605-649. doi: 10.1007/BF00992905

Tilly, Charles (2012). Contentious Performances. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Torres Santana, Ailynn (ed.) (2020). Derechos en riesgo en América Latina. Quito: Fundación Rosa Luxemburg.

Vaggione, Juan Marco (2005). “Reactive Politicization and Religious Dissidence: The Political Mutations of the Religious”. Social Theory and Practice, 31(2): 233-255.

Vaggione, Juan Marco (2014). “La politización de la sexualidad y los sentidos de lo religioso”. Sociedad y Religión, 24(42): 209-226.

Wasserman, Stanley and Faust, Katherine (2013). Análisis de redes sociales. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

1 The terms "extreme right", "far right" and "radical right" are used interchangeably to refer to what Ignazi (2003) calls the "new extreme right".

2 A motto used by civic organisations and political parties as "code" to mark their alignment with the Catholic normative framework and their opposition to progressive morality politics.

3 For more information about El Yunque see: Mata, 2015, 2021.

4 During the Transition, CISO-N leaders and activists were practising Catholics linked to "new lay movements" (mainly Opus Dei). Since the mid-2000s, they have been: 1) practising Catholics; 2) non-practising Catholics who believe in the cultural relevance of Catholicism; 3) young people socialised in lay movements; and 4) politically committed people, mostly in the PP or in Vox.

5 For more information on the important role played by Opus Dei in shaping civic mobilization in the public space to defend the Catholic normative framework, see Estruch, 1993.

6 HazteOír.org (HO) was re-founded under the name CitizenGo-HazteOir.org in 2017 following the court ruling that found evidence of its ties to El Yunque.

7 The far right had no parliamentary representation between 1982 and 2018, when Vox obtained parliamentary seats.

8 Freidin, Moro and Silenzi (2022: 37) distinguish ideological polarisation (differences between political positions) from affective polarisation (emotional aversion and distrust of political out-groups, which hinders collaboration and even inter-group socialisation).

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 189, Enero - Marzo 2025, pp. 63-92

FIGURE 1. CISO-N field cycle of protest, in relation to cultural and political opportunity structures, 1978-2023

Note: The dates associated with CISO-N organisations correspond to their founding or re-founding years; the dates associated with El Yunque indicate milestones in its relationship with the CISO-N field.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the analysis of in-depth interviews with CISO-N leaders and activists, secondary data, and netnographic data.

Image 1. Protest event against the Abortion Law, organised by Provida under the slogan “Yes to life”, Madrid, approximately 1984-1985

Note: The following slogans appear on the banners: “No to abortion”, “Abortion is killing babies”, “Yes to life”, “Why kill them”, “Abortion is a crime”.

Source: Still photograph from the institutional video of the Spanish Federation of Pro-Life Associations (FEAPV), entitled Pro-life 30th anniversary, available at: https://ap6r.short.gy/ksL7jm, access October 15, 2023.

Image 2. Protest event against equal marriage, organised by Foro Español de la Familia under the slogan “Family does matter”, Madrid, 18 June 2005

Note: Demonstration in front of Madrid City Hall. The slogans on the banners read: “Family does matter”; “Family=man and woman” (on a Vatican City flag); “Marriage=man and woman” (on a Spanish flag); “man=dad; woman=mom”; “Zapatero does not talk to families”.

Source: FEF website, available at: https://forofamilia.org/blog/algo-estamos-haciendo-bien/, access october 15, 2023.

Image 3. Vota Valores, Citizen Go-Hazte Oir’s pressure group, general election campaigns, 2023

Note: Starting at the top left-hand corner, clockwise: 1) a bus with the faces of candidates Pedro Sánchez (PSOE) and Alberto Núñez Feijóo (PP), with the slogan “Two sides of the same coin?”; 2) memes and profile pictures for social media with the slogan “Let Txapote vote for you” used to “denounce” the pacts between Sánchez’s PSOE and Catalan and Basque pro-independence parties; 3) one of the five “requests for centre-right candidates” (the other four are “repealing trans and LGBTQ+ laws; stopping the indoctrination of children in “gender ideology, LGBTQ+ and radical feminism”; “defending Christian symbols”; and “lowering taxes for families”); and 4) a voting guide with the “grades” obtained by the aforementioned candidates, plus Yolanda Díaz (Sumar) and Santiago Abascal (Vox).

Source: Vota Valores (Vote for values) website, available at: https://www.votavalores.org/, access october 15, 2023.

Image 4. Protest event against the Euthanasia Law, organised by Vividores with the support of Derecho a Vivir, anti-abortion organisation Citizen Go-Hazte Oir’s anti-abortion organisation, under the slogan “government of death”, 2021

Note: Performance carried out on the day of the passing of the Euthanasia Law (18/03/2021) in front of the Congress of Deputies (Madrid). Three of the participants are wearing black hooded robes and are carrying a scythe, representing Death. The banners bear the following slogans: “There is no right to kill”; “Killing is not progressive”; the hashtag #StopEuthanasia; and the URL of Vividores’ website.

Source: Flickr by CG-HO, access october 15, 2023.

IMAGE 5. Citizen Go-Hazte Oir campaigns against the pact between the PSOE and Catalan pro-independence parties, 2023

Note: Clockwise: call to mobilise in front of the PSOE headquarters on Calle Ferraz in Madrid; digital poster characterising the pact between the PSOE and Catalan pro-independence parties as a “coup d’état”, a frame epitomised in the hashtag #LetsStopTheCoupdetat (#ParemosElGolpeDeEstado) also used by the organisation; justification of the “rebellion against Sánchez” as a constitutional “right and duty”.

Source: CG-HO official Instagram account, available at: https://www.instagram.com/hazteoir/, access november 14, 2023.

FIGURE 2. Evolution of the network structure of both the ciso-n and expanded anti-rights fields, 1978-present

Note: The figure concentrates on the organisations that played the most prominent roles in anti-rights mobilisation, and excludes sectoral organisations (e.g. working on the bioethical, legal, education and welfare fronts) due to their more peripheral role.

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the analysis of in-depth interviews with CISO-N leaders and activists.

RECEPTION: November 15, 2023

REVIEW: March 13, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: May 22, 2024

|

Fieldwork phases |

Data collection methods |

OLIC-N organizations |

Organisations in the expanded anti-rights field |

||||||

|

Foro Español de la Familia (FEF) |

Plataforma Sí a la Vida (PSV) |

Citizen Go-Hazte Oir (CG-HO) |

Vividores |

Conferencia Episcopal Española (CEE) |

Partido Popular (PP) |

Vox |

El Yunque |

||

|

Phase 1 (2016-2020) |

In-depth interviews1 |

7 |

6 |

7 |

|||||

|

Participant observation |

Anti-abortion demonstration (Madrid, 2015) |

Anti-abortion demonstration (Madrid, 2017) |

Demonstration against abortion and "gender ideology" (Madrid, 2015). |

||||||

|

Analysis of official documents |

X |

||||||||

|

Phase 2 (2020-2022) (including the lockdown period due to the COVID-19 pandemic) |

Netnography |

||||||||

|

Press2 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

|

Official websites |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

||

|

Official Twitter accounts |

X |

X |

X |

||||||

|

YouTube platform3 |

8 |

7 |

5 |

15 |

4 |

X |

|||

Table A1. Data collection methods for organisations in the OLIC-N and the expanded anti-rights fields, Spain, years 2016-2022

1 Interviews with a purposive sample of activists with different levels of responsibility (e.g. leader, activist, occasional collaborator, supporter), carried out in Bilbao (Basque Country), Pamplona (Navarre) and Madrid.

2 Compilation of news items from ideologically diverse media outlets (both print and digital), with a special focus on Catholic and conservative media (e.g. Aciprensa, El Debate, Religión en Libertad, etc.), where most news on OLIC-Ns tend to be concentrated.

3 Compilation of interviews, presentations, seminars or workshops with people in positions of responsibility in different organisations.

Source: Prepared by the authors.

TablE A2. List of in-depth interviews conducted and main characteristics of interviewees, years 2017-2018

|

iD |

Organisation |

Position |

City |

Age |

Education Level |

Date |

|

1 |

FEAPV |

Coordinator |

Bilbao |

33 |

High |

25 January 2017 |

|

2 |

CG-HO (Derecho a Vivir) |

Volunteer |

Bilbao |

21 |

Intermediate |

26 January 2017 |

|

3 |

FEAPV |

Volunteer |

Bilbao |

18 |

High |

01 February 2017 |

|

4 |

FEAPV |

Volunteer |

Bilbao |

19 |

High |

08 February 2017 |

|

5 |

FEF |

Supporter |

Bilbao |

45 |

High |

10 February 2017 |

|

6 |

FEF |

Supporter |

Pamplona |

26 |

High |

26 February 2017 |

|

7 |

CG-HO |

Former provincial coordinator |

Pamplona |

25 |

High |

07 March 2017 |

|

8 |

FEF |

Supporter |

Pamplona |

19 |

High |

08 March 2017 |

|

9 |

FEF |

Celebrity endorser |

Pamplona |

63 |

High |

08 March 2017 |

|

10 |

CG-HO |

Supporter |

Bilbao |

22 |

High |

22 March 2017 |

|

11 |

FEAPV |

Volunteer |

Bilbao |

20 |

High |

27 October 2017 |

|

12 |

FEF |

Supporter |

Bilbao |

56 |

High |

02 November 2017 |

|

13 |

FEF |

Celebrity endorser |

Madrid |

58 |

High |

07 November 2017 |

|

14 |

PSV-Fundación Más Vida |

Managerial position |

Madrid |

25 |

High |

08 November 2017 |

|

15 |

CG-HO |

Managerial position |

Madrid |

45-55 |

High |

10 November 2017 |

|

16 |

CG-HO (Derecho a Vivir) |

Volunteer |

Bilbao |

48 |

High |

14 November 2017 |

|

17 |

CG-HO |

Supporter |

Bilbao |

56 |

High |

15 November 2017 |

|

18 |

Fundación Maternity |

Managerial position |

Bilbao |

35 |

High |

11 January 2018 |

|

19 |

FEF (Fundación Red Madre)-PSV |

Managerial position |

Madrid |

58 |

Intermediate |

13 April 2017 |

|

20 |

FEF |

Managerial position |

Madrid |

62 |

High |

16 April 2018 |

Source: Prepared by the authors.

TablE A3. Civic organisations in the OLIC-N field and political and religious organisations in the expanded anti-rights fields, 1978-2023

|

Acronyms |

Name |

English translation |

Main characteristics |

Years of activity |

|

|

Civic organisations |

|||||

|

+Libres |

Más Libres |

Freer |

Area: generalist; Mission: to defend the primacy of Catholicism, its symbols and culture; Ties: “Daughter organisation” of CG-HO. |

2011-present |

|

|

+Vida |

Más Vida |

More Life |

Area: abortion + welfare; Mission: educational and welfare work; Ties: to the FEF and the PSV since the mid-2010s it has gained increasing visibility in PSV mobilisations. |

2013-present |

|

|

Abogados Cristianos |

Fundación Abogados Cristianos |

Foundation of Christian Lawyers |

Area: legal; Mission: defend Catholicism and its centrality in culture; uses lawfare to contest freedom of expression; Ties: informal ties to GC-HO. |

2008-present |

|

|

ACdP |

Asociación Católica de Propagandistas |

Catholic Association |

Area: educational + publicity campaigns; Mission: one of the most active and oldest secular organisations in Spain; since 2010 it has used a strong strategy to gain visibility in the public sphere; Ties: strong ties to CEE and weak ties to FEF; informal ties to CG-HO. |

1909-present |

|

|

Actuall |

Actuall |

Area: communication (digital newspaper); Mission: dissemination and amplification of CG-HO protest events; Ties: "Daughter newspaper" of CG-HO. |

2015-present |

||

|

ADEVIDA |

Asociación en Defensa de la Vida Humana |

Association for the Defence of Human Life |

Area: welfare; Mission: one of the oldest anti-abortion organisations (strong welfare-based goals until the 1990s); Ties: to the FEF and informal ties to the CEE. |

1979 |

|

|

ANDEVI |

Asociación Navarra para la Defensa de la Vida |

Navarre Association for the Defence of Life |

Area: welfare; Mission: one of the oldest anti-abortion organisations (strong welfare-based goals until the 1990s); Ties: to FEF and informal ties to the CEE; Scope: Navarre province. |

1978 |

|

|

CG |

Citizen Go |

Citizen Go |

Area: internationalisation + "gender ideology" front; Mission: internationalise GC-HO mobilisation; Ties: to CG-HO. |

2013-present |

|

|

CG-HO |

Citizen Go-Hazte Oir.org |

Citizen Go-Make |

Area: generalist; Mission: defend strongly conservative positions in relation to morality politics related to private life; Ties: to all its daughter" platforms” + Vox + El Yunque. |

2017-present (2001-2017 HO) |

|

|

Cheque Escolar |

School Voucher |

Area: education; Mission: opposition to the school course “Citizenship Education” (2006) and, currently, to the dissemination of content on "sexual diversity" in schools; Ties: "daughter organisation" of CG-HO. |

2006 (partially inactive since 2013) |

||

|

CJTM |

Centro Jurídico Tomás Moro |

Thomas Moore Legal Centre |

Area: legal + training; Mission: defence of Catholicism and its culture using a lawfare strategy of to contest freedom of expression; Ties: weak ties to GC-HO and FEF. |

2007-present |

|

|

CONCAPA |

Confederación Católica Nacional de Padres de Familia y Padres de Alumnos |

National Catholic Confederation of Students’ Parents |

Area: education; Mission: defence of Catholic education and Church values in the education system; Ties: strong ties to the CEE, highly influential in the conservative Catholic sphere. |

1929-present |

|

|

DaV |

Derecho a Vivir |

Right to Live |

Area: abortion + euthanasia; Mission: publicity campaigns and performances with strong dramatic content; since 2018 it has led CG-HO anti-euthanasia mobilisations; Ties: to CG-HO. |

2008-present |

|

|

FEAPV |

Federación Española de Asociaciones Provida |

Spanish Federation of Pro-Life Associations |

Area: abortion + traditional family + euthanasia; Mission: organisation in the anti-abortion struggle, based on US pro-life organisations; since the beginning of the 2nd cycle it has also been involved in the defence of the "traditional family" and euthanasia; Ties: strong ties to the FEF. |

1981-present (follow-up organisation of PROVIDA) |

|

|

FEFN |

Federación Española de Familias Numerosas |

Spanish Federation of Large Families |

Area: lobbying + large families; Mission: advocacy for large families; Ties: strong ties to the FEF; close informal ties to the PP and the CEE. |

1967 |

|

|

FEF |

Foro Español de la Familia |

Spanish Family Forum |

Area: abortion + euthanasia + traditional family + welfare + training; Mission: bring together all the self-styled "pro-life" welfare organisations linked to the CEE; Ties: strong informal ties to the CEE; close ties to the field except to CG-HO and its related organisations. |

1999-present; (activated in 2004) |

|

|

HA |

Hay Alternativas |

There are alternatives |

Area: biomedical research; Mission: repeal laws related to assisted reproduction; Ties: "daughter organisation" of GC-HO. |

2002 (currently inactive) |

|

|

HO |

Make yourself Heard |

See CG-HO, its re-foundation since 2017. |

2001-2017 |

||

|

IPF |

Instituto de Política Familiar |

Institute of Family Policies |

Area: lobbying + Same-Sex Marriage; Mission: Lobby group formed against Same-Sex Marriage. Its activity is unclear (not a visible organisation in the public space); Ties: strong ties to El Yunque and CG-HO. |

2006-present |

|

|

Jérôme Lejeune |

Fundación Jérôme Lejeune |

Jérôme Lejeune Foundation |

Area: abortion + biomedical research; Mission: defence of science based on Christian principles. It is currently one of the leading scientific groups in the field; Ties: to FEF and especially +Vida. |

Established in 1995 (in Spain since 2008) |

|

|

Mis Hijos |

Mis Hijos, Mi Decisión |

My Children, My Decision |

Area: lobbying + education; Mission: fight against sex education in schools; Ties: “Daughter organisation” of CG-HO. |

2019-present |

|

|

No es Igual |

No es Igual |

It is not the same |

Area: lobby + traditional family; Mission: fight against the legalisation of Same-Sex Marriage and adoption by same-sex couples; Ties: "daughter organisation" of GC-HO. |

2004-2005 |

|

|

Plataforma Cada Vida Importa |

Plataforma Cada Vida Importa |

Every Life Matters Platform |

Area: traditional family + anti-abortion + euthanasia; Mission: repeal the law on abortion, Same- Sex Marriage and euthanasia; Ties: FEF. |

2009-2015 and 2021 (inactive) |

|

|

PpE |

Profesionales por la Ética |

Professionals for ethics |

Area: bioethics; Mission: to promote science based on Christian principles. Activity in the field not entirely clear; Ties: in the area of influence of El Yunque and CG-HO. |

1992-present |

|

|

PROVIDA |

Fundació PROVIDA |

Pro-Life Foundation |

Area: abortion + welfare; Mission: repeal abortion and euthanasia laws; Ties: FEF. |

1977-1981 (re-founded as FEAPV) |

|

|

PSV |

Sí a la Vida Plataforma |

Yes to Life Platform |

Area: abortion + euthanasia; Mission: repeal abortion and euthanasia laws; Ties: strong ties to the FEF and FEAPV. |

2011-present |

|

|

Vividores |

Vividores |

People Living Life to the Full |

Area: euthanasia; Mission: prevent the legalisation of euthanasia; Ties: "Daughter organisation" of the ACdP and linked to FEF. |

2020-2021 (inactive) |

|

|

Vota Valores |

Vote for Values |

Area: lobby + political; Mission: lobby conservative political parties and guide their political actions; Ties: "Daughter organisation" of GC-HO. |

2013-present |

||

|

Political organisations |

|||||

|

Alianza Popular |

Alianza Popular |

Popular Alliance |

Liberal-conservative political party, founded mostly by former Francoist hierarchs. |

1976-1989 |

|

|

El Yunque |

El Yunque |

The Anvil |

See note 4. |

1953-present |

|

|

Fuerza Nueva |

Fuerza Nueva |

New Force |

Extreme right-wing political party. |

1976-1982 |

|

|

PP |

Partido Popular |

Popular Party |

Centre-right political party. |

1989-present |

|

|

PSOE |

Partido Socialista Obrero Español |

Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party |

Political party with a social democratic ideology. |

1879-present |

|

|

UCD |

Unión de Centro Democrático |

Union of the Democratic Centre |

Right-wing "reformist" political party. |

1977-1983 |

|

|

UP |

Unidas Podemos |

Together we can |

Left electoral coalition. |

2016-2023 |

|

|

Vox |

Vox |

Voice |

Extreme right-wing political party. |

2013-present |

|

|

Religious organisations |

|||||

|

CEE |

Conferencia Episcopal Española |

Spanish Epsicopal Conference |

An institution that brings together a nation’s bishops for the joint exercise of some functions. Body that plays an intermediary role between the Vatican, believers and public institutions. |

1966-present |

|

TablE A3. Civic organisations in the OLIC-N field and political and religious organisations in the expanded anti-rights fields, 1978-2023 (Continuation)

TablE A3. Civic organisations in the OLIC-N field and political and religious organisations in the expanded anti-rights fields, 1978-2023 (Continuation)

TablE A3. Civic organisations in the OLIC-N field and political and religious organisations in the expanded anti-rights fields, 1978-2023 (Continuation)

Source: Prepared by the authors based on the analysis of primary and secondary data.

Table A4. Laws against which OLIC-Ns and the expanded anti-rights field have mobilised, Spain, 1978-2023

|

SEXUAL AND REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH + VOLUNTARY INTERRUPTION OF PREGNANCY |

|

|

Law 45/1978 UCD (Suárez) |

|

|

Organic Law 9/1985 PSOE (González) |

|

|

Organic Law 2/2006 PSOE (Rodríguez Zapatero) |

|

|

Ministry of Health measure (2009) PSOE (Rodríguez Zapatero) |

|

|

Organic Law 2/2010 PSOE (Rodríguez Zapatero) |

|

|