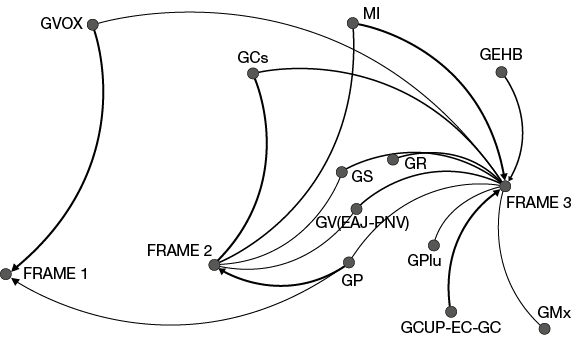

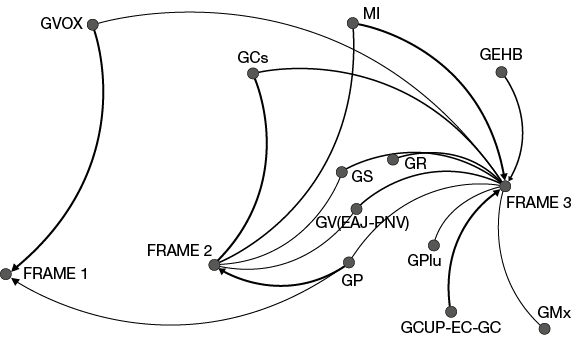

Graph 1. Graph 1. Dynamics between frames

Source: By authors using Gephi20.

doi:10.5477/cis/reis.189.131-148

Political Frameworks for Gender-based Violence

in Spain during the 14th Legislature (2019-2023)

Los marcos políticos de la violencia de género en España durante

la XIV Legislatura (2019-2023)

Marisa Revilla-Blanco and Anabel Garrido-Ortolá

|

Key words Gender-based Violence

|

Abstract During Spain’s 14th Legislature, legislative proposals were developed addressing different aspects of violence against women, with some of them providing an advance in the recognition of rights and the different types and effects of violence. The two issues guiding this article are the content of the different political frameworks for understanding violence against women and the key factors involved in defining it. To further our understanding, we apply frame analysis to the debates held in the Congressional Commission on Gender Equality and distinguish three interacting frameworks that support three positions: one that challenges the existence of specifically gender-based violence, one that maintains the current state of understanding, and one that offers a transformative perspective. |

|

Palabras clave Violencia de género

|

Resumen Durante la XIV Legislatura se desarrollaron propuestas legislativas que han abordado distintos aspectos de la violencia contra las mujeres, algunas de ellas avanzando en el reconocimiento de derechos y de diferentes tipos y efectos de la violencia. Las dos preguntas que guían este artículo abordan la consideración de los contenidos de los diferentes marcos políticos de la violencia hacia las mujeres y la comprensión de los factores clave que permiten definirlos. Para avanzar en su respuesta, se aplica un análisis de marcos a los debates sostenidos en la Comisión de Igualdad del Congreso que permite distinguir tres marcos en interacción que sustentan tres posiciones: la impugnatoria, la que mantiene el estado actual y la transformadora. |

Citation

Revilla-Blanco, Marisa; Garrido-Ortolá, Anabel (2025). “Political Frameworks for Gender-based Violence in Spain during the 14th Legislature (2019-2023)”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 189: 131-148. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.189.131-148)

Marisa Revilla-Blanco: Universidad Complutense de Madrid | mrevilla@cps.ucm.es

Anabel Garrido-Ortolá: Universidad Complutense de Madrid | angarrid@ucm.es

Introduction1

In 2004 Spain passed Organic Law 1/2004 on December 28 on Measures for Comprehensive Protection against Gender Violence (BOE no. 313 on 29/12/2004), which entered into effect in January 2005. This legislation was pioneering internationally in recognising violence against women specifically exercised in the domestic sphere by a partner or ex-partner (Pastor-Gosálbez et al., 2021). One of the priorities of the government at that time, led by Rodríguez Zapatero, was in response to the demands of feminist organisations in Spain for the recognition of the existence of violence specifically aimed at women2. In addition, the presence of feminist movements on the local level was a determinant in the adoption of comprehensive standards on the national level for the protection of women against gender-based violence (Htun and Weldon, 2012: 548). We must also note the prior ratification of a State Pact Against Gender-based Violence [Pacto de Estado Contra la Violencia de Género] in 2017 under the governing Partido Popular and with the support of the majority of parliamentary groups in the Spanish Congress, without any votes against it and with the only abstention being the parliamentary group of Unidas Podemos.

This article focuses on the 14th legislature in Spain (2019-2023), with a coalition government formed between the Spanish Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) and Unidas Podemos (UP), with Irene Montero of the UP as minister of the Ministry for Equality. Regarding violence against women3, in this legislative period advances occurred in two aspects: first, in terms of sexual freedom4, with the law known as “only yes is yes” [solo sí es sí] referring to consent, and secondly, in improving the protection of orphans that have been victims of gender-based violence5. This legislative work was marked by controversy within the governing coalition because of differences between representatives from the UP and from the PSOE, especially with the entry into force of the “only yes is yes” law (Casqueiro and Chouza, 2023).

In the case that concerns us here, the conception of gender-based violence, there is a tension based on conflicting positions on the political spectrum. These range from the recognition of “male violence”6, 7 and the broadening of the recognition of violence in other spheres, such as obstetric, political and digital violence, to the denial of the existence of any violence that is specifically exercised against women, a position that is gaining in institutional presence with the participation of the right-wing party Vox in diverse municipal and regional governments in Spain.

These dynamics show that parliamentary discourses related to this issue in Spain are changing. In this context, the present study attempts to identify the main policy frameworks regarding gender-based violence and analyse the dynamics in their development during this legislative period. With this as the aim, in section 2 we look at international legislation and its transformation in relation to key concepts linked to gender-based violence, as well as related theoretical debates. In section 3, we explain the methodology used to analyse the components of the frameworks and their application in the Spanish case. We also propose frameworks based on identifying the main positions held on the issue for the period being analysed and analyse their dynamics.

State of the question on gender-based violence: international legal acquis

and theoretical approaches

The aim of this study is to identify both key elements in the discussion of violence against women and the components and frameworks that currently articulate the different interpretations of the phenomenon in the Spanish parliament. To do this, we look at what are the key factors for understanding the differences in these frameworks and the dynamics between frameworks and the positions of the parliamentary groups in the Spanish Congress. We note, therefore, that the review of the historical and theoretical development of the concepts8, as well as the abundant empirical evidence of the existence of violence against women in the world, exceed the objectives of this article.

To contextualise the discussion, we begin the review looking at the construction of international law on this issue.

First, within the United Nations (UN), the Vienna Declaration (1993) provided a recognition of violence against women as a violation of human rights. Specifically, in article 3.38, it declares the need for “the elimination of violence against women in public and private life” and “all forms of sexual harassment, exploitation and trafficking in women” (UN, 1993b: 21). At the end of 1993, the UN General Assembly approved a Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women, which defines this as:

Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.

This definition, still in effect, encompasses sexual violence in the family and community, as well as “physical, sexual and psychological violence perpetrated or condoned by the state” (UN, 1993a).

Although these tools were an advance in the international sphere in giving attention to violence against women, it would not be until the 4th UN Conference in Beijing (1995), through the efforts of women’s organisations, when it began to be seen as a social and international problem. Since 1996, the Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) has assumed leadership in reviewing the implementation of the Beijing Platform for Action (UN 1996). In 2013, the 57th session on the “Elimination and prevention of all forms of violence against women and girls” took place.

Secondly, in the European sphere, we must mention two agreements that address violence against women, although from different perspectives. These are the Convention on Action Against Trafficking in Human Beings (Warsaw, 2005) and the Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul, 2011). The Warsaw Convention specifically addressed the trafficking of persons and forced prostitution, emphasising “preventing, suppressing and punishing trafficking, especially of women and children” (Art. 39). Along these lines, the EU directive on the prevention and combating of human trafficking and the protection of victims – arising from the 2005 Warsaw Convention –recognises “the gender-specific phenomenon of trafficking and that women and men are often trafficked for different purposes” (2011/36/UE: 1). The directive on sexual assault and female genital mutilation should also be mentioned in reference to sexual freedom (2007/73).

For its part, the Istanbul Convention passed in 2011 by the Council of Europe launched a legal tool that, broadly and comprehensively, addressed violence against women and domestic violence. Specifically, it recognized the structural nature of domination and discrimination against women by men. The text was ratified by Spain in 20149 and, since May 2017, with accession to the EU Council, acquired a binding character for all member countries. However, due to conservative resistance to its application, it was not until six years later (in May 2023) that the European Parliament finally ratified it. The resistance can be seen in the fact that there are still countries that have not signed the Convention10, as well as in the revocation of its ratification by Turkey in 2021.

In March 2022, the European Commission adopted a proposed Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on combating violence against women and domestic violence. In 2024, after two years of negotiations, an agreement was reached on this Directive, which includes the extension of criminalisation to female genital mutilation, forced marriage and cyber-violence. However, the agreement does not include “criminalisation of rape based on lack of consent” (COM/2022/105: 4), an issue that is delaying the adoption of the Directive due to opposition from different states.

As can be seen in this review, the concept that is most commonly used in international law and agreements is “violence against women”.

In regard to theoretical debates, this concept, also widely used, stands out because it identifies who is the recipient of violence, women, but does not point out its causes. For this reason, feminist analyses argue for the use of other concepts, such as patriarchal violence, male violence or sexist violence, which identify the cause of the violence that is aimed at women, while also pointing to its use within specific power relations (Osborne, 2009: 30).

Two concepts appear in debates that are related to the sphere in which violence occurs: “domestic violence” and “family-based violence”. The use of these concepts has radically different consequences for understanding the phenomenon.

In the first case, the use of “domestic violence” is an identification of private space as one of the spaces in which violence against women occurs (Alberdi and Mata, 2002: 79-86). In fact, it is found that the largest proportion of cases of violence against women are carried out by a husband, partner or a close family member, while in the case of violence against men, violence is most often carried out by a person who is not known by the victim (Bloom, 2008: 14). The risk of this approach is that a reductionist equivalence is made between domestic violence, violence against women and gender-based violence. This has happened in Spain with the passage of the Comprehensive Law Against Gender Violence (Bonet, 2007: 38; Pastor-Gosálbez et al., 2021: 118).

In the second case, the use of “family violence” or “intra-family violence”, the subject that potentially faces the violence is not the woman, but any member of the family. This concept also does not identify the man as the aggressor, rather, it implies that violence can be exercised by any family member.

Regarding this latter interpretation, it is important to understand that, starting from the rupture of the duality of woman as victim and man as aggressor, we arrive at two very distinct theoretical and policy positions:

The gaze… [is shifted] from violent men to a hetero-patriarchal capitalist society that is based on maintaining inequalities to perpetuate itself (Biglia, 2007: 32).

The latter position leads us to what is perhaps the more widely considered concept of “gender-based violence”. Although, as Peate points out, “gender-based violence” and “violence against women” are frequently used interchangeably (2019: 607), the reality is that the theoretical discussion over the concept of gender has been transferred to the conception of gender-based violence. This shift means that, currently, two theoretical interpretations compete for understanding:

Gender-based violence as equivalent to violence against women. Critical feminist sectors warn that the concept of gender can be a euphemism that hides the fact that relations between the sexes are power relations (Osborne, 2009; 30). However, as Renzetti and Campe point out, this equivalence recognises that most of the violence against women is based on gender, which means that it is an expression of inequality in power between men and women (2021: 411).

Gender-based violence as a broader phenomenon than violence against women and includes the latter. In the forward to their book, Biglia and San Martín argue that:

If personalization silences social responsibility in the perpetration of gender-based violence, feminist silence in the face of the falsity of this representation makes it complicit, in the majority of cases unconsciously, of gender-based violence exercised in relationships that are not inscribed in “hetero-patriarchal normality” (Biglia and San Martin, 2007: 11).

In fact, their approach involves the resignification of gender-based violence.

In line with this second interpretation, Bloom (2008: 14) contributes the following definition:

Gender-based violence (GBV) is the general term used to capture violence that occurs as a result of the normative role expectations associated with each gender, along with the unequal power relationships between the two genders, within the context of a specific society. [Violence against women and girls] constitutes a part of GBV. Men and boys can also be victims of GBV11.

Based on this analysis it follows that these concepts are under debate. In fact, there are different positions within different feminisms (Renzetti and Campe, 2021: 415). There also exist a broad number of studies and positions from Black feminists and indigenous feminists that argue that a feminist perspective on gender-based violence must transcend understanding it as exclusively an expression of patriarchy to understand it as structural violence (Hall, 2015: 397-398).

Therefore, the conception of violence requires identifying the factors associated with who can exercise violence, over whom and understanding the causes attributed to this violence.

Discourses on violence against women in the parliamentary sphere

To meet our objective, we analyse parliamentary debates and legislative production during the 14th Legislature (2019-2023) using discourse analysis and frame analysis. We use the concept of “frame” or “framing” to refer to:

[…] messages that define communicative intentions in the sense in which a picture frame demarcates the painting inside it and allows the painting to be distinguished from the walls that surround it (Rivas, 1998: 182).

Following this author, we emphasise that frames have a dynamic and collective character and are important in social relations. They are “a collective production” (Rivas, 1998: 182). Lastly, as a guide for the analysis, we incorporate a number of the methodological approaches used by P.P. Donati (as discussed by Rivas):

[…] the units of analysis are texts that constitute acts of language of an actor or voice, oral or written, defined by a beginning and an end; they are the smallest textual units to which a complete meaning can be attributed. Discourse analysis attempts to reconstruct the argumentative structure that is used to define and give meaning to a question or object. From this perspective, a text is considered to define the research object based on a framework. And given that frames are used to define objects, it is not very likely that texts exist with many frames. Coding will consist in the classification of relevant texts based on the frame that is used to define the research object. Lastly, it will constitute the text corpus, from which a sample of texts can be drawn (Rivas, 1998: 198).

For the analysis we focus on the activity of the Commission for Equality of the Congress of Deputies. We do not consider the Commission for Monitoring the State Pact against Gender-based Violence, as we see it as being of a fundamentally technical nature. Nor do we consider the Senate Commission for Equality, as all decisions have to ultimately be approved by the Congress. As a result, to extract a text corpus we have worked with the session reports for the twenty-nine sessions of the Commission for Equality of the Congress, which begin on 7 February 2020 with the constitution of the commission and ended on 23 February 2023 with its dissolution.

The method of frame analysis is qualitative. We used atlas.ti to help in systematising the information gathered. The initial approach was based on two categories extracted from the theoretical analysis: 1) how violence is defined, and 2) who violence is aimed at. The initial extraction of texts was carried out based on a search for the following concepts: male violence(s); violence(s) against women; gender-based violence(s); domestic violence(s) and family violence(s). The latter categories were included to include discourses that deny the violence that specifically women suffer. For the category of whom violence is aimed at, we used the following sub-categories: women, girls, children, sons and daughters, elderly, others. All these categories were analysed in all the interventions gathered in the mentioned session reports.

This initial extraction of texts allowed us to identify some of the key issues that articulate and differentiate the discourses, which helped us to reformulate the components with which to continue organising the formulation of the frames. Regarding the concept of violence, it was essential to consider what actions are included. In addition, although we began with an assumption of the existence of a consensus regarding who carries out these acts of violence, that is, certain men, from reviewing the extracted texts we found that this consensus was under debate. As a result of these findings, we include the third and fourth components as indicated below. In short, the coding of the components in the extraction of the texts was carried out according to the following guidelines: 1) Definition of violence; 2) At whom it was aimed; 3) Actions that are considered and 4) Who exercised the violence (the developed coding can be found in Appendix 1).

Key Themes of the debate in the components of the frames

In analysing the components we take three dimensions that could affect the dynamic of interactions into account: 1) the temporal dimension (were there changes in the components and in the dynamic of the frames over the period of the legislature?); 2) the thematic dimension (effect on what is being discussed) and 3) the dialectic dimension (effect on who is being spoken to). As we will see in what follows, we have not found evidence of an effect of the temporal dimension in this legislature. The largest effect observed is in the thematic dimension: we find that the content of the proposals addressed in each commission session can modify the discourse in the case of certain groups. Lastly, the dialectic dimension can be observed in the interactions, primarily of the Vox (GVox) Parliamentary Group toward Minister Montero.

Component 1: Definition of violence

This component reveals three substantive positions:

If we compare the three definitions of violence, the first one sees sex as playing no role in domestic or intra-family violence:

Parliamentary Group Vox considers all persons, independent of their sex, age or sexual orientation, to be entitled to protection, because they are susceptible to suffering intra-family violence. Therefore, we do not understand why this law is only for women (Toscano de Balbín, DSCD-14-CO-275:5).

The second one is predominantly based on concepts such as “violence against women” and “gender-based violence”, referring to the violence that is exercised over women for the fact of being women, although, on occasion, it is argued that there is an “ideology” that sustains this violence. This is explained by Rosa Maria Romero Sánchez (GP):

Two million women unemployed is a personal and family drama, because it limits women’s autonomy, freedom and independence. Which makes them more vulnerable to gender-based violence (DSCD-14-CO-407: 23).

The third uses the connotation of violence as male violence and, therefore, as structural, in many cases, adding the use of concepts of gender-based violence and violence against women:

The question of terminology is not a minor one. We have spent many years trying to go from domestic violence to gender-based violence to then male violence. It is not trivial, because you know perfectly well that gender is the social construction of stereotypes and attributions to each one of the theoretically biological sexes and it was, therefore, basically a way of agreeing between those who did not quite believe that this existed and those who were completely convinced that patriarchy did indeed exert its violence on women in multiple ways. Therefore, that the term used is “male violence” seems to me to be the most adequate for this type of legislation, Carolina Telechea, Republican Parliamentary Group (GR), (DSCD-14-CO-233: 56).

Lastly, as we see in this last intervention; we should emphasise the distinction in the use of the singular and plural. The GP and the Parliamentary Group of the Ciudanos party (GCs) when they use the adjective “machista”, always do so using violence in the singular; while the rest of the groups, with the exception of GVox, including the minister, tend to use violence in plural, to include each and every one of the forms that male violence takes.

Component 2: At whom violence is aimed

The core of the debate is articulated over whether women are or are not victims of violence. It is a debate based on the dichotomy men/women. The statement of Ana María Zurita (GP) that “the sex of active and passive subjects is a key element” (DSCD-14-CO-363: 32), divides the roles of victimizer (man) and victim (woman). At the other extreme, we find the first variation of “it’s not only women” that suggests that, as Toscano de Balbín (GVox) states, “what is the most unjust and intolerable is that your approaches exclude all types of domestic violence except that aimed at heterosexual women” (DSCDE-14-CO-221: 11). This perspective is that domestic violence can be exercised over any member of the family and, as we will see when we discuss component 4, any member of the family can exercise that violence, including women.

We must also point out that a different formulation of “it’s not only women” who are victims of male violence exists; we find three versions:

This widening of the recognition of the subjects that can be victims of sexist violence must be compared with another perspective that appears in the same debate. In the latter case, the focus is on the dichotomous axis man/woman, pointing out that it is women that are subject to violence, but recognising the diversity of women and the importance of intersectionality (functionality, age, origin, economic resources, education)13. In addition, in some interventions the conception of “women” is opened up to both cis women and trans women14.

Component 3: Actions that are considered violent

First, the denial of violence that is specifically exercised against women eliminates from debate consideration of the forms in which it can happen, leaving only one sphere: the family and in the domestic space. This position adds two issues: recognition of Parental alienation syndrome (PAS) as intra-family violence, a defence made by Toscano de Balbín, (DSCD-14-CO-841) in the presentation of a so-called non-law proposal [Propuesta No de Ley (PNL)] made by GVox, regarding PAS, and consideration of the voluntary interruption of a pregnancy as violence that is exercised against women, Méndez Monasterio, (GVox), (DSCD-14-CO-817).

When debate takes place within the conception of violence as structural violence, the existence of multiple and diverse forms of violence are recognised: during this legislature there is recognition of certain specific forms, such as “vicarious violence”15, “obstetric violence”16 and “digital violence”17.

One specific debate refers to male violence that is expressed through the “commodification of women’s bodies”, Laura Berja Vega, Grupo Parlamentario Socialista (GS), (DSCD-14-CO-41). The first issue related to this formulation is prostitution: as Berja states, for “the PSOE, prostitution is a clear form of sexual violence, of tremendous male violence” (DSCD-14-CO-678: 15). Along these lines, the minister, Montero, also makes a similar argument:

This ministry and this minister would like to abolish prostitution, and I say it being aware of the importance that these words have for many women and for many other feminists” (DSCD-14-CO-743).

However, Mar García Puig, speaking for the Parliamentary Group representing the confederation of the parties Unidades Podemos-En Comú Podem-Galicia en Común (GCUP-EC-GC) argued for the need to distinguish two ways of exercising prostitution: on the one hand, sexual exploitation and forced prostitution, and on the other, what is referred to as sex work (DSCD-14-CO-169).

The second issue that is included in this formulation of the “commodification of bodies” is referred to as “reproductive exploitation”. Regarding this concept, there is a clear consensus expressed by different parliamentary groups in rejecting the practice of surrogacy. In the case of GVox, “we call them wombs to rent”, Méndez Monasterio (DSCD-14-CO-233: 46). While Montero referred to the “misnamed wombs to rent”, (DSCD-14-CO-516: 13), and Berja Vega (GS) to “a body so that someone else gives birth” (DSCD-14-CO-761: 17). In the case of the GCUP-EC-GC, Sofia Fernández Castañon used the term “substitute gestation”, but also emphasised that this “is not a technique of assisted reproduction, but exploitation and male violence” (DSCD-14-CO-233: 50).

Lastly, the debate over the adequacy of measures is in line with the recognition of the state pact as a convenient tool to tackle gender-based violence, which is at the core of the GP’s position. In this sense, Rosa Romero (GP) in a statement aimed at the Ministry for Equality (ME) would say that “it is the best instrument that is in their hands to find against gender-based violence” (DSCD-14-CO-407: 22) and demanded “a ministry that truly is dedicated to prioritising the pact against gender-based violence” (DSCD-14-CO-532: 37). In addition, defence of this pact is based on achieving consensus:

The great value of this pact was that we were able to reach an agreement among all the parliamentary groups present at that time, putting an issue that united us above all else, and we gave it the character of a state pact; it is one of the few state pacts that exist in this country, Pilar Cancela Rodríguez (GS) (DSCD-14-CO-407: 34).

The Ministry for Equality also defended the pact, revealing an institutional position and, a search to advance and broaden the pact as well. Noelia Vera (ME) argued: “We always say that this is an institutional pact, but that it is also a political and social pact. It is a pact that has to go far beyond this chamber” (DSCD-14-CO-407: 4).

Component 4: Who exercises violence

The debate around who exercises violence refers to two dimensions, the perpetrator of violence and the context in which that violence occurs.

In the first dimension, the general consensus, established in the state pact, indicates men as the subjects that exercise violence over women. This premise is found in the expression “passive subject, active subject”, Zurita Expósito, GP, (DSCD-14-CO-363: 32). All the parliamentary groups, with the exception of GVox, share this position, although with some slight differences. In some cases, men are situated in the social structure (machismo, patriarchy). This use of the plural men refers to “healthy sons of the patriarchy; they are anybody” according to secretary of state Angela Rodríguez Martínez (DCSD-14-CO-761: 23). Similarly, and following the ME, the government delegate against gender-based violence, Victoria Rossell, indicates that there are no racial or economic traits that identify who commits violence against women (DCSD-14-CO-783).

When prostitution was debated, specific perpetrators are mentioned: the pimp and criminal networks, suggesting changes in the criminal code for:

[…] the prosecution of those who profit from using premises on a regular basis for the sexual exploitation of women and, therefore, for the violation of a human right, a fundamental right, minister Montero (DCSD-14-CO-169: 11).

The denial of the existence of specifically gender-based violence on the part of GVox leads the group to articulate a discourse disputing the actor that carries out violence, placing the focus on women as perpetrators of violence. Thus, we find in the reply made by Méndez Monasterio to Montero:

Why, Madam Minister, do you not prosecute violence against children? Why, regarding violence against children, when in the murders of newborns 18.3% are committed by women and 1.3% by men (DSCD-14-CO-41: 28).

Although GVox states that all individuals may suffer violence, the group articulates a new discourse related to the violence that women suffer, connecting it to a context that is specific to other cultures: they are women, but “women in the Islamic world”, Toscano de Balbín (DSCD-14-CO-275: 6). These positions appear, primarily, in the discussion of the PNL (PSOE) in relation to developing a comprehensive approach to female genital mutilation. In this case, Edurne Uriarte Bengoechea (GP) relates this practice with “Islam” (DSCD-14-CO-587: 36). Both interventions establish a correlation between Islam and violence against women: as argued by María Teresa López Álvarez (GVox):

Spain has become a destination point for persons of ethnicities with cultures, with traditions, with rituals that practice this violence that has nothing to do with Spanish culture (DSCD-14-CO-587: 35).

Lastly, we also consider a debate on the vulnerability women face in the labour market, placing the focus on unemployment among women and addressing limitations resulting from the lack of “autonomy, freedom and independence [and how this] makes women more vulnerable to gender-based violence”, Romero Sánchez (GP) (DSCD-14-CO-407: 23). This debate, although addressing issues rooted in women’s living conditions that generate greater vulnerability, does not focus on the problem of the exercise of this violence, blurring the boundaries of responsibility and ignoring, as pointed out by Lidia Guinar Moreno (GS) “the cross-class socioeconomic nature and complexity of gender based-violence” (DSCD-14-532:38); or, as Fernández Castañón states (GCUP-EC-GC) “[that] fundamental rights do not depend on having a job” (DSCD-14-CO-516: 39).

Proposed framing for the analysis

In this section we identify the main frames for analysing current parliamentary debate. To do this, following the methodological discussion presented, we use a phrase that characterises the framing based on the conceptualisation of violence and we present its components. To understand the dynamics of the frames we refer to their use by different parliamentary groups in different contexts and in interactions.

Frame 1. Individuals have no gender (DSCD-14-CO-443:31)

In this framing, gender is denied as a social fact and considered to be “an ideological fact” (DSCD-14-CO-443: 31). That women are subject to violence because they are women is also rejected. The violence that occurs happens within the family; it is intra-family violence and any member of the family can be violent or be at the receiving end of violence. The violence aimed at women for being women is associated with other cultures. Its existence in Spain is due to practices, such as genital mutilation, introduced by immigrant populations. Similarly, women are also understood to be aggressors, a situation that, according to this interpretation, is not considered in the relevant legislation.

Frame 2. For women to be free of violence what they need is to have freedom and economic independence (DSCD-14-CO-532:36)

This framing considers gender-based violence as the same as violence against women, but does not establish a cause for this violence. It uses the duality man-active, woman-passive regarding violence. One of the main components is defending the existing legal framework in Spain: the Comprehensive Law Against Gender-based Violence and, fundamentally, the State Pact Against Gender-Based Violence.

Regarding responsibility, this framing blurs the context because it is defined as “a question of state”, while also pointing to the living conditions of the victims of violence: It follows that economic independence is a condition for leaving violence. To a certain extent, a link is made between the precarious employment many women face and greater difficulty in escaping from violence.

Frame 3. But everyone now knows that it’s misogynist violence (DSCD-14-CO-233:10)

This frame defines violence as structural. The variations in the components include the use of concepts such as macho or sexist by different parliamentary groups. Violence is also used in both singular and plural forms and its most comprehensive version refers to “patriarchal violence”.

This framing involves more debate than the others. Thus, one debate is over whether it is only women (with intersectionality and, depending on the case, including trans women or not) who are victims of violence. This is related to the theoretical approach in which gender-based violence is broader than violence against women. It also includes deeper debate over which forms of violence are included, beyond the consensus on the definition of violence against women as derived from the international normative framework: we are referring to debates on prostitution and on reproductive exploitation, a brief discussion of which are found in the explanation of component 3. Regarding who exercises violence it points to systemic and structural elements18.

Dynamic between frames

and parliamentary groups

The dynamics between the frames can be grouped into three interactions (Graph 1):

In short, the parliamentary groups reveal shifts between the frames, including in those cases in which they maintain a clear position within a specific frame (GVox in frame 1, GP in frame 2 and ME in frame 3). GVox shifts to frame 3 with reproductive violence, while the ME has a clear presence in frame 3 but closely followed by a presence in frame 2 related to its defence of the state pact. The GP reveals the most diverse positions because, although it is representative of frame 2, it also adheres to a component in each of frames 1 and 3. In frame 3 we find the ME and GCUP-EC-GC, both adhere to four components in frame 3. In the case of the latter, it is only found in frame 3, although, with fewer components than the GEHB, GR, the Plural Parliamentary Group (GPlu) and GMx. It should be noted that while Frame 3 is the one with the greatest presence of different parliamentary groups, the link between the GCUP-EC-GC and the ME reveals that the two share a common agenda.

An initial conclusion resulting from our analysis of the political frames used to understand gender-based violence in Spain is that a change has occurred: there has been a breakdown of consensus on the existence of violence against women as a specific problem in Spanish society. The state pact and the law itself, constitute a minimum consensus today regarding a legal framework that protects women from the violence against them.

Currently, when so-called family violence is referred to in Spain, it is not only in reference to the sphere in which violence against women can occur. In reality, several things are being claimed: that violence specifically against women does not exist, that violence is not directed at women because they are women and that women also exercise violence against men, children and the elderly.

Agirretxea Urresti, GV (EAJ-PNV) suggests that those who think that violence specifically against women does not exist “must live on a different planet”. But the existence of this political position converts the state pact, as the very commission has pointed out, into a treasure that must be guarded because, in the 14th legislature, there were not the conditions for its broad support in the parliament.

Regarding the proposed frames, they serve to define and establish political positions that are not, in any way, static positions; rather, we find a dynamism between the frames that reveals political tensions and how parliamentary groups share and dispute these frames. In addition, the analysis of the proposed frames shows three political positions on defining violence and on the approach to taking action: one of contestation/conflict, one of maintaining the statu quo and one that is transformative. The conflictive position has gained in presence in the parliament with the incorporation of GVox but is not specific to Spain. It is the national representation of the anti-feminist component of the discourse of the ultra-right not only in Europe, but in the United States as well (Cabezas, 2021).

To conclude, we propose some research issues that will permit us to advance our understanding of these issues. First, would be analysis of the processes behind, and causes of, the changes in discourses regarding gender-based violence. Secondly, would be research on the reach that the positions challenging the existing legislation on public policies and instruments for the protection of women could have, both within Spain and in other countries and in international and supranational institutions. Finally, would be understanding the resonance that the framework denying male violence can have, especially among the younger population, both men and women.

Alberdi, Inés and Matas, Natalia (2002). La violencia doméstica. Informe sobre los malos tratos a mujeres en España. Barcelona: Fundación La Caixa.

Biglia, Bárbara (2007). Resignificando “violencia(s)”: obra feminista en tres actos y un falso epílogo. En: B. Biglia y C. San Martín Martínez (coords.). Estado de wonderbra: Entretejiendo narraciones feministas sobre las violencias de género: 21-34. Barcelona: Virus Editorial.

Biglia, Bárbara and San Martín Martínez, Conchi (coords.) (2007). Estado de Wonderbra. Entretejiendo narraciones feministas sobre las violencias de género. Barcelona: Virus Editorial.

Bonet, Jordi (2007). Problematizar las políticas sociales frente a la(s) violencia(s) de género. In: Biglia, B. and San Martín Martínez, C. (coords.). Estado de wonderbra: Entretejiendo narraciones feministas sobre las violencias de género (pp. 35-48). Barcelona: Virus Editorial.

Bloom, Shelah (2008). Violence Against Women and Girls. A Compendium of Monitoring and Evaluation Indicators. USAID-East Africa/IGWG.

Cabezas, Marta (2021). “Silencing Feminism? Gender and the Rise of the Nationalist Far Right in Spain”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 47(2): 319-345. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/716858

Casqueiro, Javier and Chouza, Paula (2023). “El PSOE sacará la reforma de la ‘ley del solo sí es sí’ con la derecha al romperse el bloque progresista”. El País, 4 March. Available at: https://elpais.com/espana/2023-03-04/el-psoe-sacara-la-reforma-de-la-ley-del-solo-si-es-si-con-la-derecha-al-romperse-el-bloque-progresista.html

Hall, Rebeca (2015). Feminist Strategies to End Violence against Women. In: B. Rawwida and W. Harcourt (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Transnational Feminist Movements. Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199943494.013.005

Hanmer, Jaina and Maynard, Mary (eds.) (1987). Women, Violence and Social Control. British Sociological Association. The MacMillan Press.

Htun, Mala and Weldon, S. Laurel (2012). “The Civic Origins of Progressive Policy Change: Combating Violence against Women in Global Perspective, 1975-2005”. American Political Science Review, 106(3).

Juárez-Rodríguez, Javier and Piedrahita-Bustamante, Pedro (2022). “Discursos populistas y negacionistas de la violencia de género y la diversidad sexual en la pospandemia. Análisis del caso Vox en España”. International Visual Culture Review / Revista Internacional de Cultura Visual, 12(1): 2-12. doi: https://doi.org/10.37467/revvisual.v9.3716

Kreft, Anne-Katrin (2022). “This Patriarchal, Machista and Unequal Culture of Ours: Obstacles to Confronting Conflict-Related Sexual Violence”. Social Politics, 30(2): 1-24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxac018

López, Silvia (2011). “¿Cuáles son los marcos interpretativos de la violencia de género en España? Un análisis constructivista”. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 25: 11-30.

Osborne, Raquel (2009). Apuntes sobre violencia de género. Barcelona: Edicions Bellaterra.

Pastor-Gosálbez, Inma; Belzunegui-Eraso, Ángel; Calvo Merino, Marta and Pontón Merino, Paloma (2021). “La violencia de género en España: un análisis quince años después de la Ley 1/2004”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 174: 109-128. doi: https://reis.cis.es/index.php/reis/article/view/160

Peate, Ian (2019). “Gender-based Violence”. British Journal of Nursing, 28(10). doi: https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2019.28.10.607

Renzetti, Claire and Campe, Margaret (2021). Feminist Praxis and Gender Violence. In: N. A. Naples (ed.). Companion to Feminist Studies. New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons Ltd. (1st edition).

Rivas, Antonio (1998). El análisis de marcos: Una metodología para el estudio de los movimientos sociales. In: Los movimientos sociales. Transformaciones políticas y cambio cultural. Madrid: Editorial Trotta.

Session reports for the Equality Commission of the Congress of Deputies (14th Legislature)

DSCD-14-CO-41 (2020). 24 February 2020. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-41.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-169 (2020). 7 October 2020. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-169.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-221 (2020). 6 November 2020. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-221.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-233 (2020). 18 November 2020. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-233.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-275 (2021). 27 January 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-275.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-334 (2021). 23 March 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-334.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-363 (2021). 15 April 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-363.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-407 (2021). 25 May 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-407.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-443 (2021). 23 June 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-443.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-516 (2021). 20 October 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-516.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-532 (2021). 26 October 2021. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-532.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-587 (2022). 2 February 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-587.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-595 (2022). 22 February 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-595.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-678 (2022). 18 May 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-678.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-743 (2022). 21 September 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-743.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-761 (2022). 8 October 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-761.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-783 (2022). 18 October 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-783.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-817 (2022). 29 November 2022. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-817.PDF

DSCD-14-CO-841 (2023). 8 February 2023. Available at: https://www.congreso.es/public_oficiales/L14/CONG/DS/CO/DSCD-14-CO-841.PDF

Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (2005). Warsaw, 16.V, Complete list of the Council of Europe’s treaties- n.° 197 (Warsaw Convention, 2005). Available at: https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list?module=treaty-detail&treatynum=197

The Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence (2011). Series -No. 210 (Istanbul Convention, 2011). Available at: https://rm.coe.int/1680462543

Directive 2011/36/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 April 2011 on preventing and combating trafficking in human beings and protecting its victims, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2002/629/JHA. 5 April 2011 Official Journal of the European Union. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2011/36/oj

Proposal for a directive of the european parliament and of the council on combating violence against women and domestic violence COM/2022/105 final, 8 April 2022. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52022PC0105

United Nations (UN, 1946). Resolution of the Economic and Social Council. Adopted 21 June 1946. Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/resolution/gen/nr0/043/49/img/nr004349.pdf?token=Myilie0jZmsPLXEhLF&fe=true

United Nations (UN, 1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Adopted and proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on 10 December 1948 (General Assembly resolution 217 A). Available at: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/2021/03/udhr.pdf

United Nations (UN, 1979). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women. Adopted and opened for signature, ratification and accession by General Assembly resolution 34/180 of 18 December 1979. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/cedaw.pdf

United Nations (UN, 1993a). World Conference on Human Rights, Vienna, 1993. Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/g93/142/33/pdf/g9314233.pdf

United Nations (UN, 1993b). Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women Proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 48/104 of 20 December 1993. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/eliminationvaw.pdf

United Nations (UN, 1996). Resolutions and Decisions of the Economic and Social Council 1996. Available at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n97/775/21/pdf/n9777521.pdf

Appendix 1. Frames and components (with coding)

|

Frame 1: Individuals have no gender |

|

1-1-1 Gender is a linguistic matter and, therefore, is is also an ideological matter |

|

1-2-1 “It is not only women” |

|

1-3-1 Family violence + PAS |

|

1-4-1 “Violence has no sex” + immigrants, other cultures |

|

Frame 2: For women to be free of violence what they need is to have freedom and economic independence |

|

2-1-2 “Violence has gender, but no ideology” violence against women = gender-based violence |

|

2-2-2 “On issues of male violence, the sex of the active and passive subjects is a key factor” |

|

2-3-2 “The State Pact against gender-based violence is the best tool that we have to fight against gender-based violence” |

|

2-4-2 Men + Socioeconomic and labour market context |

|

Frame 3: But everyone now knows that it’s misogynist violence |

|

3-1-3 Structural violence (debate over the definition of violence) |

|

3-2-1 “It is not only women” |

|

3-2-1-a “All individuals that are not CIS men, hetero and with the power that the patriarchy gives them” |

|

3-2-1-b “Lack of protection of groups such as Trans” |

|

3-2-1-c “The life of children and of women” |

|

3-2-2 It is women |

|

3-2-2-a Intersectionality |

|

3-2-2-b CIS and Trans women |

|

3-3-3 “Each and every one of these forms of male violence” |

|

3-3-3-a Obstetric violence |

|

3-3-3-b Political violence |

|

3-3-3-c Digital violence |

|

3-3-4 “Commodification of women’s bodies” |

|

3-3-4-a Prostitution |

|

3-3-4-b Reproductive exploitation |

|

3-4-2 Men, heterosexuals… (pimps) + “machismo”, patriarchy |

1 This article is the result of the research project “Contemporary Women’s Movements and Feminism in Spain: Political Dynamics” [Movimientos de Mujeres y Feminismos Contemporáneos en España. Dinámicas Políticas], reference number: PR44/21-29934. Proyectos Santander-UCM. An earlier version was presented at the 27th IPSA World Congress of Political Science in Buenas Aires, Argentina, 15-19 July 2023.

2 Pastor-Gosálbez et al. (2021) carried out an exhaustive analysis of both the process that led to the development of the law and the results of the institutionalisation of the fight against gender-based violence. The study by Alberdi and Mata (2002) continues being key in making this phenomenon visible in Spain, providing data and statistics and analysing the different types of violence against women, as well as their causes.

3 It should be noted that when we refer to “violence against women” we include violence against girls.

4 Organic Law 10/2022, 6 September, on comprehensive guarantee of sexual Liberty (BOE, no. 215, of 07/09/2022).

5 Organic Law 2/2022, 21 March, on improving the protection of orphan victims of gender-based violence (BOE no. 69, of 22/03/2022).

6 On November 22, 2022, the 2022-2025 State Strategy to Fight Male Violence was passed.

7 Translator’s note: the original text refers to violencia machista, which is here being translated as male violence. “Machista” implies certain beliefs or attitudes held my men, while the term “male violence” does not clearly do so.

8 Some references for reviewing this development: Hammer and Maynard, 1987; Alberdi and Matas, 2002; Biglia and San Martín, 2007; Bloom, 2008; Osborne, 2009; Renzeti and Campe, 2021; Keft, 2022.

9 Instrument for ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence against Women and Domestic Violence, carried out in Istanbul, 11 May 2011 (BOE-A-2014-594).

10 Among the countries that have not signed the Convention are Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia.

11 The author points out that her book focuses on violence against women and girls.

12 To save space we have decided not to indicate the date of each reference. In the bibliography, we include the Session Reports used, with their corresponding dates.

13 GCs, Sara Giménez Giménez (DSCD-14-CO-275); director of the Instituto de las Mujeres, Toni Morillas González (DSCD-14-CO-595); Isabel Pouzeta Fernández, GEH Bildu (DSCD-14-CO-275); Ismael Cortés Gómez, GCUP-EC-GC (DSCD-14-CO-443).

14 Mar García Puig, GCUP-EC-GC (DSCD-14-CO-233); María Carvalho Dantas, GR (DSCD-14-CO-841).

15 Minster for Equality Irene Montero, appearance at her own request, 21 September 2022 (DSCD-14-CO-743) and Secretary of the State for Equality and Against Gender-based Violence, Ángela Rodríguez Martínez (DSCD-14-CO-761).

16 Sofía Fernández Castañón, GCUP-EC-GC (DSCD-14-CO-595), Pozueta Fernández, Parliamentary group Euskal Herria Bildu (GEHB), (DSCD-14-CO-817; DSCD-14-CO-817).

17 Secretary of State, Rodríguez Martínez (DSCD-14-CO-761) and “political violence”, Secretary of State, Noelia Vera Rodríguez (DSCD-14-CO-221), director of the Instituto de las Mujeres, Morillas González (DSCD-14-CO-334).

18 It could be said that this component already appeared in what López distinguishes as the “dominant” frame (2011: 28). However, first, we are not suggesting that frame 3 is dominant, but that it is the most widespread among the parliamentary groups. Secondly, another of the components of this dominant representation is under discussion, that which only refers to “male violence within heterosexual couples” (López, 2011: 28). This frame 3 abandons this component.

19 To be able to show the dynamics of the different parliamentary groups, we have assigned a numeric value based on the components present in each frame (from one to four), revealing, in this way, the level of adhesion to and articulation of the debates over the frames and their interactions. We have used the Gephi programme that allows us to visualise the relationship and the degree of incorporation (greater or lesser intensity of the arrows) of the components in the groups’ discourses.

Reis. Rev.Esp.Investig.Sociol. ISSN-L: 0210-5233. N.º 189, Enero - Marzo 2025, pp. 131-148

Graph 1. Graph 1. Dynamics between frames

Source: By authors using Gephi20.

RECEPTION: November 27, 2023

REVIEW: March 14, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: June 12, 2024

Source: Developed by the authors.