doi:10.5477/cis/reis.193.71-88

Social Imaginaries and Ecological Transition: Spain 2050

Imaginarios sociales y transición ecológica: el Plan España 2050

Daniel Lara de la Fuente and Manuel Arias Maldonado

|

Key words Degrowth

|

Abstract Environmental sustainability plays an increasingly important role in the European Union’s political agenda. Spain 2050, a document published by the Spanish government in 2021, laid the discursive foundations for a sustainable Spain. This article seeks to elucidate what this ideal entails. We draw on discourse analysis to identify the categories, concepts and metaphors that construct a narrative about the causes of and solutions to sustainability issues within the text. The results suggest an eclectic view of sustainability. The document supports a reformist discursive ideal, while also setting out guidelines for limiting human activity that reflect survivalist and degrowth-oriented environmental discourses. In practical terms, this eclectic discourse involves a pluralist conception of sustainability. |

|

Palabras clave Decrecimiento

|

Resumen Si la sostenibilidad medioambiental juega un papel creciente en la agenda política de la Unión Europea, el plan España 2050, publicado en el año 2021, fijó las bases discursivas de la España sostenible. Este artículo elucida cuál es ese ideal. Para ello, recurrimos al análisis del discurso: rastreamos la presencia en el texto de las categorías, conceptos y metáforas que componen un relato acerca de las causas y las soluciones de los problemas de sostenibilidad. Los resultados sugieren una visión ecléctica de la sostenibilidad. El documento es favorable al ideal discursivo reformista, si bien establece pautas de restricción de la actividad humana correspondientes a discursos medioambientales survivalistas y decrecentistas. En términos prácticos, este eclecticismo discursivo supone una concepción pluralista de la sostenibilidad. |

Citation

Lara de la Fuente, Daniel; Arias Maldonado, Manuel (2026). “Social Imaginaries and Ecological Transition: Spain 2050”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 193: 71-88. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.193.71-88)

Daniel Lara de la Fuente: Virginia Tech | dalara@vt.edu

Manuel Arias Maldonado: Universidad de Málaga | marias@uma.es

Spain 2050 was presented to the public in the spring of 2021. It was a document prepared by the National Office for Foresight and Strategy (Oficina Nacional de Prospectiva y Estrategia (hereinafter, the ONPE)) with the aim of providing Spanish society with “a rigorous and holistic diagnosis of the challenges that Spain will face” (La Moncloa, 2021). This public agency had been established a year earlier to join what has become known as the EU-wide Foresight Network (hereinafter, the Network). Following the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, it aimed to develop political mechanisms among European Union Member States for anticipating long-term challenges with significant transformative potential. Built by the European Commission in partnership with Member State governments, the Network has since published annual strategic reports analysing the major challenges of the coming decades and potential approaches to overcome them. This public agency has two national precedents in Europe: the Finnish Commission for the Future, inaugurated in 1993 (FG, n.d.), and the British Foresight programme, dating back to 1994 (Georghiou, 1996).

Despite the media stir caused by the issuance of the Spain 2050 report, the visibility of the body responsible for its drafting has since declined in the Spanish public sphere. Initially established in January 2020 as a Sub-secretariat under the President’s Office tasked with advising ministries on public policy development, in November 2023 it was downgraded to the status of a Directorate General within the General Secretariat for Public Policies, European Affairs and Energy Foresight.

In the absence of definitive knowledge regarding the ONPE’s future performance, the Spain 2050 document remains its most significant contribution to date. There is no evidence that its findings have influenced the direction of the successive governments led by socialist President Sánchez. Nevertheless, its content deserves some consideration: the study was prepared with the assistance of one hundred experts from various disciplinary fields with the aim of understanding the challenges and opportunities that Spain will face in the coming decades, which, in turn, would allow for the creation of a Long-Term National Strategy based on “a multi-stakeholder dialogue”. The report’s outcome is just one of many possible results. The choice of experts and the political orientation of the commissioning government indicate that an alternative set of experts under a different government would likely have produced a markedly distinct foresight document. The challenges and opportunities under assessment, however, would not have differed: productivity, education, ageing, climate change and inequality are all choices that are hardly subject to debate.

This article aims to analyse the implicit assumptions made in the section of the document concerned with climate and environmental challenges. Discourse analysis is used to identify the social imaginaries informing the various strategic proposals contained in the text. The basic premise is that it is not possible to isolate the set of discourses, narratives or imaginaries about sustainable and desirable socio-natural relations and the means to achieve them. Imaginaries are understood to be ideal visions of a desirable society, which are called upon to influence public perceptions and to guide the real-world action of the individual or collective stakeholders who adhere to them. The definitive feature of imaginaries is that they take a utopian form. In this context, the “futurity” inherent in sustainability, traditionally framed as an ideal state of relations between society and nature to be achieved at some undefined point in the future, encourages speculation about what this “sustainable society” might ultimately look like. It is important to attend to the sustainability part of the report, as ecological transition policies are synergistic with other areas that the report also considers to be fundamental. Notable objectives include adopting a new model of economic growth that is more productive and efficient in its use of resources and in reducing environmental impacts by economic activity; readapting the Spanish labour market to the new technological developments to be generated, as required by this model; and maintaining a sustainable, equitable territorial policy that balances the social, ecological and economic impacts of ongoing urbanisation processes.

The article is organised as follows. The next section is devoted to contextualising the notion of ecological imaginary within the framework of strategic foresight. The third section outlines the methodology applied, defining both the research techniques used and the discourses that embody different ecological imaginaries. Section four presents the results obtained. Finally, conclusions are drawn from the analysis and possible avenues for future research are provided.

Social imaginaries and strategic foresight in the Anthropocene

Climate change and energy transition should be understood within the framework of the Anthropocene (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2000), a term that describes the “human epoch” we have entered, after the accumulation of anthropogenic impacts on natural systems has ultimately affected the functioning of what has become known as the “Earth system” (see Ellis, 2018; Zalasiewicz, 2022). Among these impacts are those related to the alteration of the climate system, caused by the massive concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (mainly CO2, methane and nitrous oxide) that has been happening since the onset of industrialisation (see Maslin, 2021: 1-18). But other anthropogenic phenomena are equally significant, such as the loss of biodiversity, ocean acidification, the multiplication of waste, increasing urbanisation, the creation of massive infrastructures, the use of fertilisers and other artificial enablers of food production, and alterations in the water cycle (see Steffen, et al., 2015).

All these changes create an urgent need for action. It is not a matter of choosing whether or not we will live in the Anthropocene, but of influencing the type of Anthropocene in which we will live; rather than it being good or bad, the Anthropocene is simply “inescapable” (Dryzek and Pickering, 2019). This does not in itself point to what specifically should be done; this question is open to technical discussion, moral debate and political controversy. Therefore, it makes sense to refer to specific social imaginaries: aspirational narratives or discourses that define an ideal horizon grounded in a set of normative assumptions and outline the means through which the proposed process of transformation is to be realised.

In liberal democracies, what has been called strategic foresight reflects the imaginaries that permeate the public sphere. Strategic foresight has been defined as a medium- and long-term public policy domain aimed at informing decision making through structured, inclusive, systematic and participatory processes of collective intelligence (EC, n.d.). These processes bring value in five areas (Störmer, et al., 2020: 132): 1. They develop anticipatory governance capacities to tackle medium- and long-term challenges; 2. they raise policy-makers’ awareness of the significance of these challenges; 3. they enable policy-makers to take measures that best match the scale and nature of the specific challenge at hand; 4. they underscore the need for action to address problems whose cumulative effects and future impact are not immediately or intuitively apparent; and 5. they promote evidence-based public policies by fostering collaboration between experts and decision-makers.

The instruments used include: a) the analysis of megatrends (which are understood as large-scale processes with a broad temporal and transformative scope); b) the planning of possible scenarios by the use of interviews with experts and mathematical models; c) horizon scanning, for early detection of change drivers; and d) envisioning desirable futures (EC, n.d.). The socio-ecological issues arising from the Anthropocene encompass these areas. For example, the European Commission has identified climate change as a megatrend (EC, 2024). Developing effective policies for climate change mitigation and adaptation requires drawing on a well-informed understanding of the phenomenon and ensuring that decision-makers are aware of the scale of the problem, with the aim of anticipating or reducing its effects; for example, droughts or the intensification of an atmospheric phenomenon called cut-off low in eastern Spain (also known by the Spanish acronym DANA).

Building on the “envisioning” function performed by strategic foresight, the central hypothesis formulated in this article is that the sustainable Spain depicted in the Spain 2050 document envisages a desirable future, in which the reformist imaginary of ecological modernisation predominates. However, this is compatible with a prominent role for survivalism and economic rationalism and, to a lesser extent, degrowth. Consistent with the usual framing and current trajectory of European environmental policies, the advocacy of disruptive technologies central to the ecomodernist imaginary is discarded. The main basis for this hypothesis lies in the course set by European environmental policies, which are marked by strict regulations on controversial technologies such as nuclear energy and genetic engineering for agricultural purposes, while simultaneously promoting a green growth model centred on renewable energy and the gradual reduction of pesticide use to foster more organic farming. Hence, for example, the Spanish government’s willingness to eliminate nuclear energy from the energy mix. In order to test this hypothesis, it is necessary to first define these imaginaries, as well as the methodology and the focus of the article.

Environmental discourse analysis (see Dryzek, 2022; Hajer, 1995) and qualitative content analysis (see Schreier, 2012) were used to carry out the research. The use of both techniques was deemed complementary due to their suitability for addressing two distinct phases of the research process. Environmental discourse analysis was employed as a basis for the operationalisation process, in order to identify and define the imaginaries associated with sustainability that guide the analysis. Building on this conceptual foundation, qualitative content analysis enabled us to 1) develop a coding frame consisting of what Schreier referred to as main dimensions or categories and their corresponding subcategories (Schreier, 2012: 5); and 2) design and implement a strategy to segment the information in relation to these, working alongside discourse analysis.

Environmental discourse analysis

The imaginaries of the Anthropocene can be interpreted as intelligible discourses that contend with each other in the public sphere. Discourse is understood as a set of linguistic regularities made up by ideas, concepts and categories through which meaning is given to a phenomenon (Hajer and Versteeg, 2005: 175). Discourse analysis detects regularities and interprets the meaning and influence of categories, concepts and linguistic resources in specific contexts. In this case, the context was the foresight policy of the Spanish government; the phenomenon, ecological transition, with special emphasis on its climate and energy component.

Discourse analysis has a long tradition in the study of environmental policy and political processes in the English-speaking sphere. Its merits include one that is particularly important for the purposes of this article (see Hajer and Versteeg, 2005: 175-180), as it allows us to unravel the power that discourses have in shaping what can be “thought” in a given situation. This is because discourses account for reality on the basis of a specific categorical system, delimiting the boundaries of the represented reality (Dryzek, 2022: 9). Finally, this analysis can show the implicit assumptions involved in the different discourses.

The analytical approach is composed of three elements. The first is the conception of discourses as “stories” (Hajer, 2006: 69) that have a beginning, a middle and an end. In this case, the beginning narrates how and why we have arrived at an unsustainable situation in Spain. The middle, or transit towards a sustainable Spain in 2050, tells the story of how this final stage is to be reached. The end marks the aspirational horizon: a sustainable Spain in 2050. The results will be presented using this narrative outline. The second element is the “argumentative approach” (Hajer, 1995: 52-58), according to which discourses have an unequal presence and are therefore organised hierarchically depending on their degree of presence in each case. In the scenario at hand, this coexistence reflects a dispute over the leading role of the Government’s foresight agenda. This is why Spain 2050 does not provide a fully coherent account of the causes of and solutions to environmental problems; rather, it shows some overlapping, mutually conflicting categories, concepts and resources. The third element is “discourse coalitions” (see Hajer, 1995: 58 and 2006: 70), which highlights that various stakeholders share the use of a set of meanings. In this sense, the Spain 2050 document is not only a reflection of a dispute between different discursive practices, but also of their possible points of convergence1. Thus, imaginaries can be grouped into two discursive coalitions (see Table 1), according to the analytical framework created by John Dryzek (2022). On the one hand, reformism and, on the other, environmental radicalism. In turn, a distinction should be made within each bloc between a “prosaic” approach (accepting the rules of the existing political game) and an “imaginative” approach (proposing new rules).

TablE 1. Ecological transition discourses

|

Reformism |

Radicalism |

|

|

Prosaic |

Economic rationalism |

Survivalism |

|

Imaginative |

Ecological modernisation, ecomodernism |

Degrowth |

Source: Dryzek, 2022.

That said, we will define each environmental discourse identified:

1. Degrowth. Originally a normative and empirical critique of economic growth as practised in capitalist societies, degrowth is also a proposal for a cultural reorientation that should lead to a society radically different from the present one. It proposes an equitable and sustainable reduction of social production, meaning the amount of materials and energy that are extracted, processed, transported, distributed, consumed and disposed of by human communities (Kallis, 2011: 874). To achieve this, societies and their economies must be downsized; production, commerce, consumption and transport must be significantly reduced. This will result in a life that is more local and less mobile, but also more egalitarian and sustainable, while remaining democratic (see Jackson, 2009). True emancipation will occur in a society that rejects growth, where a human being’s “true” nature is found in sufficient consumption (Princen, 2005: 140). Insofar as it provides a different answer to the question of what it means to live well, degrowth could operate as “a social imaginary guiding new political thinking for the Anthropocene” (Reichel and Perey, 2018: 246-247).

2. Survivalism. Survivalism dates back to the 1970s and 1980s (see De Geus, 1999). Its importance in the public sphere arose after the publication of the 1972 Report to the Club of Rome entitled The Limits to Growth (see Meadows et al., 1972), and was updated after the popularisation of the concept of “planetary boundaries” (Röckstrom, et. al., 2009). The difference between the two frameworks lies in their respective emphasis on different strands of the ecological crisis (Dryzek, 2022: 43). While the Report to the Club of Rome emphasised scarcity and potential resource depletion in the future, the notion of planetary boundaries delimits a safe ecological space measured in environmental impacts. This space has two “core” boundaries, namely climate change and biodiversity loss (Steffen, et al., 2015: 736), from which seven others can be derived: altered phosphorus and nitrogen cycles, ocean acidification, introduction of plastics into natural systems, stratospheric ozone depletion, changes in land use and freshwater use (see Steffen, et al., 2015). Survivalism envisions an ecologically disruptive future brought about through elite-driven policies. For example, through Earth system governance (see Biermann, 2014) in order to ensure minimum planetary habitability. These two frameworks can be compounded by the “ecological footprint” framework (Rees and Wackernagel, 1996), proposed and popularised during the 1990s, which still holds some influence in environmental policy advising.

3. Ecomodernism. Officially launched with the publication of a manifesto in 2015 (see Asafu-Adjaye et al., 2015), ecomodernism is a doctrine with an imaginary called the “good Anthropocene” which seeks to creatively adapt contemporary societies to new global environmental conditions without relinquishing the achievements of Western modernity. Thus, sustainability can and must be combined with political liberalism, technological innovation and economic growth. But ecomodernism is transformative because of its commitment to controversial technologies in Western societies, such as nuclear energy and genetic engineering, among others. This approach gives the State an active role in seeking the technological, legal and political innovations needed to achieve the so-called “good Anthropocene” (see Symons, 2019). Its scope is global: ecomodernism aspires to a global economic convergence in which humanity can enjoy the fruits of modernity (Karlsson, 2018: 80) through an abundant and efficient supply of clean energy that would help eradicate poverty and boost productivity, supporting a worldwide process of urbanisation and industrialisation (Bazilian and Pielke, 2013). Ecomodernism therefore affirms the ability of human beings to circumvent ecological limits in imaginative ways, in opposition to the idea that the Anthropocene inevitably diminishes human possibilities.

4. Ecological modernisation. This discourse was the “systemic” response of liberal democracies when confronted with the challenge of sustainability in the 1980s. In contrast to survivalism, modernists posited the possibility of an ecological reform of liberal society (see Simonis, 1987). As in ecomodernism, it was assumed that human progress throughout history has been real and remains possible if rational measures for ecological reform are applied (see Mol et al., 2009). The innovation needed to achieve this goal would be produced by scientists, businesses and markets, and regulated by governments; other civil society stakeholders would be tasked with creating a new political culture, new consumption patterns and new lifestyles consistent with the pursuit of sustainability. The implementation of technologies, however, would follow the precautionary principle (see Hajer, 1995; Toke, 2011). Both the prevention and regulation required to make it effective form a reformist standard that is ideally established through a consensus among governments, businesses, social and civic movements, and the scientific community (Dryzek, 2022: 176). While ecomodernism advocates that a key role should be played by the State, ecological modernisation prioritises private entrepreneurs and decentralised public administration (see Murphy, 2000; Jänicke, 1990).

5. Economic rationalism. This discourse is supported by those who defend the ability of markets to achieve public goals (see Dryzek, 2022: 125 ff.). Public environmental management is viewed with suspicion, except for the design and establishment of markets where this is necessary for sustainability. The tools available to economic rationalism include privatising public goods, such as granting private property rights over natural resources (land, water) to encourage a more efficient use; introducing incentives through green taxation to influence the behaviour of companies and consumers; and creating markets that raise the cost of externalities, thereby driving technological innovation (which enables fossil fuel emission trading schemes, as exemplified by the European CO2 market). Economic rationalism has an anthropocentric ethos, as it does not initially consider granting special protection to the natural world. Nevertheless, it possesses an instrumental quality that would allow its tools (incentives, taxation and markets) to be used within a social framework that would prioritise such protection, since their use could prima facie be limited to achieving specific objectives in particular contexts.

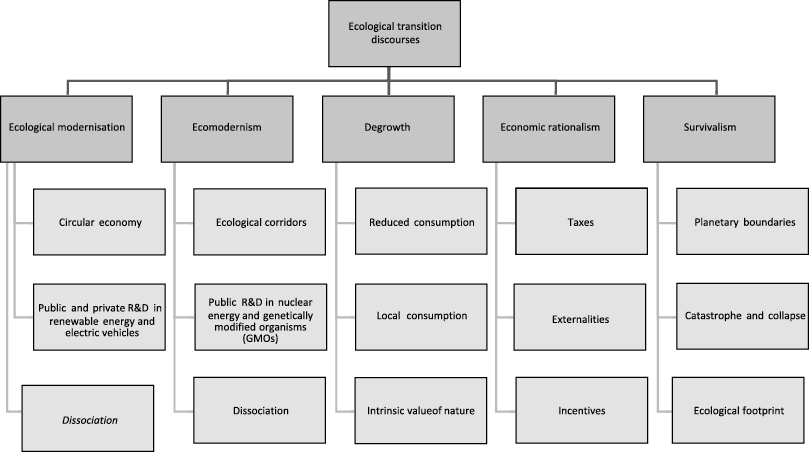

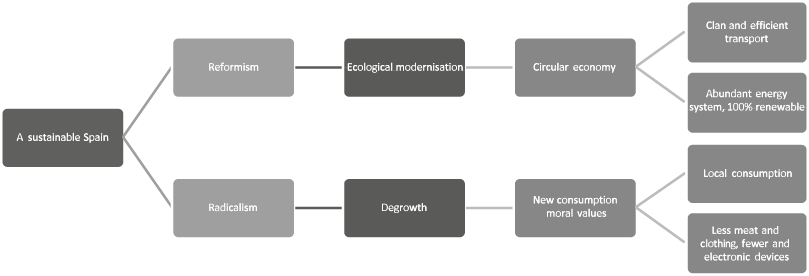

Discourse analysis is part of a sequential process of qualitative content analysis (see Schreirer, 2012) that records the following phases. First, two basic research questions were formulated: What visions of a sustainable society prevail in the Spanish government’s foresight policy? And what are their meanings? Second, the chapter of the Spain 2050 report that focused on ecological transition was selected as a case study, as it presents the foresight vision of a sustainable Spain clearly, concisely and explicitly. Third, a hierarchical coding framework (see Figure 1) was established to order and analyse the information contained in the material by means of inductive and deductive strategies. An inductive strategy was used in the initial analysis of the information. This preliminary analysis helped identify its alignment with discourses examined in previous literature. A more in-depth review of this literature then made it possible to define these discourses more precisely. In turn, these were operationalised as categories with a view to deductively examining the material related to these categories, this time in a systematic way.

Fourth, a set of indicators or subcategories was established to identify each discourse or category during the analysis and interpretation process, thereby organising the information. The information was then analysed to verify how the material aligned with the proposed subcategories, following the use of a manual procedure to segment the information according to these selected subcategories and their corresponding categories or dimensions. Given the limited amount of material, the manual procedure was deemed to offer greater analytical depth and flexibility compared to the use of software, without compromising the time and labour efficiency of the research process. This approach prioritised interpreting the semantic relevance of the selected categories over quantifying terms or expressions. Fifth, content was segmented by theme, corresponding to the division of the story of a sustainable Spain following the three-pronged structure of beginning, middle and end. The coding unit varied according to the needs associated with the research objectives, and ranged from a single sentence to a full paragraph. Sixth, the information that had been analysed and previously coded was interpreted in order to verify which categories were semantically preponderant in the analysed material; that is, to verify which views of or discourses about a sustainable Spain had the most decisive influence on the foresight vision of the national government.

The following problems were identified and addressed during the research process. The first concerned the choice of the unit of analysis. The word was initially considered to be the unit of analysis, based on the idea that its membership to a subcategory could be potentially clarified by its relationship to context units. An example of this could be the term “R&D”, which characterises both ecomodernism and ecological modernisation, and could be accompanied by different types of technologies, whether precautionary or not. In order to reduce the complexity of the segmentation process, it was decided to generate subcategories that would allow broader units of analysis to be established. This issue concerning the “R&D” subcategory relates to a broader problem: the difficulty in meeting the methodological requirement of having mutually exclusive units of analysis, whereby subcategories must correspond to only one dimension (see Schreier, 2012: 75). Thus, in order to ensure the validity of the analysis, two distinct subcategories were established: “Public R&D in nuclear energy and genetically modified organisms (GMOs)” and “Public/private R&D in renewable energy and electric cars”. This criterion of mutual exclusivity, however, could not be met with regard to the subcategory of “dissociation”. This is because it is an essential concept for both ecomodernism and ecological modernisation. However, due to its possible associations with the two subcategories mentioned above, this exception did not compromise the analysis. Thus, environmental impacts and resource use can be dissociated from economic growth either by the use of nuclear energy and GMOs (typically included in the “ecomodernism” category), or by the adoption of renewable energy sources and electric cars (typically included in the “ecological modernisation” category).

A third conceptual problem could be that the reader might interpret the established subcategories as saturating the battery of theoretical meanings associated with each environmental discourse or category in every case and scenario. For example, degrowth not only emphasises the need to consume less and de-escalate our economies to be sustainable, but the imperative to do so in a different way (i.e. by instituting a new form of collective ownership to replace private ownership). As this premise was not included as a subcategory due to its lack of relevance to the material analysed, the subcategories used for analysis should not be understood as fully encompassing the theoretical characteristics of the categories included.

Results: The story of a sustainable Spain in 2050

The analysis confirmed the hypothesis formulated at the onset: the discourse of ecological modernisation was hegemonic in the ideal of ecological transition in the foresight document. Although the role of this discourse was secondary to that of survivalism in defining the problem, ecological modernisation took a leading role in both the middle part and the end of the story. This reformist horizon (based on introducing technological innovations guided by the precautionary principle and seeking mutually beneficial solutions in the economic and environmental spheres, through concerted efforts between public and private stakeholders) was complemented by elements of economic rationalism. Degrowth had a notable—albeit minor and subsidiary—presence with respect to the means for achieving sustainability. Ecomodernism barely left a trace.

Defining the problem: overshooting

and lack of efficiency

Humanity has already exceeded several of the planet’s biophysical limits and, if it remains on its current course, will eventually cause an unprecedented environmental catastrophe (ONPE, 2021: 190).

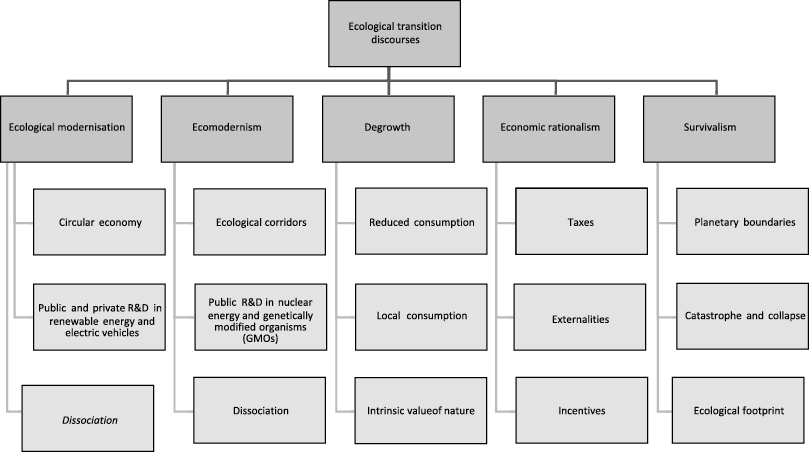

This statement frames how and why the problems to be solved during the ecological transition have arisen (see Figure 2). This framework is dominated by survivalist discourse, according to which Spanish society is in the process of overshooting its ecological limits after having experienced unprecedented economic and demographic growth over the last seventy years. The notion of overshoot inaugurated the survivalist framework in 1972, following the Limits to Growth report. In turn, this discourse has branched out into two broad frameworks: the ecological footprint and planetary boundaries. Both share the framing of the problem as undesirable overshoot, but provide their own metrics; however, only the ecological footprint concept has been operationalised on a national scale. This became evident in the Spain 2050 document, as the overshooting of the ecological footprint was the central assumption underpinning the diagnosis of the problem. As stated in the document: “If all of humanity consumed as we do today, it would take two and a half planets to meet these needs” (ONPE, 2021: 172). If this fact is ignored, the outcome is certain: ecological destabilisation, understood as catastrophe or collapse. Although the idea of collapse has been gaining ground within contemporary survivalism (see Bardi, 2020), the Spain 2050 document merely pointed it out as the inevitable consequence of maintaining the current growth model.

There are two reasons why Spanish society has overstepped its ecological limits, according to the tenets of radicalism. The first is an inappropriate relationship with the natural environment, which should be radically changed. While the document does not explain what this destructive type of relationship between humans and nature is, we can infer that it alludes to unreflective anthropocentrism: a conception whereby the natural environment is merely seen as a supplier of goods for humans, without deserving greater ethical consideration, not even for strictly self-interested reasons. To a large extent, this critique of anthropocentrism is more explicit within degrowth approaches, since the intrinsic value of nature is one of its assumptions (see Demaria et al., 2013: 196). This is all the more evident when one notes that, as with the literature and statements of degrowth activists (see Degrowth.info editorial team, 2020; Kallis, et al., 2020), the document points to the COVID-19 pandemic as the turning point in the transvaluation of anthropocentrism. The second reason is an empirical claim commonly used in degrowth discourse, that of the “rebound effect”. This term refers to a phenomenon in which— notwithstanding the fact that technological progress reduces the resources required per unit of goods and services produced—the concomitant decline in their economic cost gives rise to increased demand compared with the technologies they replace. Paradoxically, both resource consumption and its environmental impact would increase in aggregate, stimulated by the increase in demand. And ecological problems would be aggravated because, even if the Spanish population consumed more efficient goods and services, their ecological impact would be greater.

The reformist framework tempers the potential collapse-oriented drifts of the radical section in the document. Proof of this is the counterbalance provided by the modernising ecological discourse, which is underlined by the document’s emphasis on two key elements. The first is that Spain has not been able to change its economic growth model, based on an agricultural industry and a transport system that is as obsolete as environmentally damaging; and the second is that it has not been able to promote a more efficient and innovative productive fabric in order to reduce its ecological footprint. Its public and private sectors have under-invested in research and development, which has prevented the dissociation of economic activity from its environmental effects. Indeed, the concept of dissociation—also referred to as “decoupling”—is criticised in the document. This contradiction proves the plausibility of one of our premises, namely that environmental policy stages the clash between dissimilar and even antagonistic discursive forces.

Moreover, the report highlights that Spain’s environmental record has not only been negative, but has also exhibited some positive aspects. Thus, it is claimed that Spain ranks among the top 15 countries worldwide in environmental performance; is a leading country in the number of biosphere reserves; has improved efficiency in urban water consumption; and has promoted progressive laws and policies for adaptation to climate change. The jewel in the crown is the advance of photovoltaic energy, considered the energy of the future not only because of the climatic conditions in Spain, but also because of its concomitant potential opportunities in terms of the generation of green hydrogen. Hence the optimistic statement summarising the modernising reformist framework: “the country is capable of delivering major change when it sets its mind to it” (ONPE, 2021: 175).

This reformist orientation is complemented by the presence of economic rationalism. It is also argued that Spanish governments have indirectly promoted environmentally harmful economic activities by only timidly using fiscal and monetary incentives; similarly, the State has collected fewer green taxes than its counterparts in neighbouring countries. The most important example is water, which is too cheap despite its scarcity.

The road to sustainability: technology replacement, taxation and consumption

We need to prosper in a more balanced way, meeting people’s needs within the planetary boundaries (ONPE, 2021: 191).

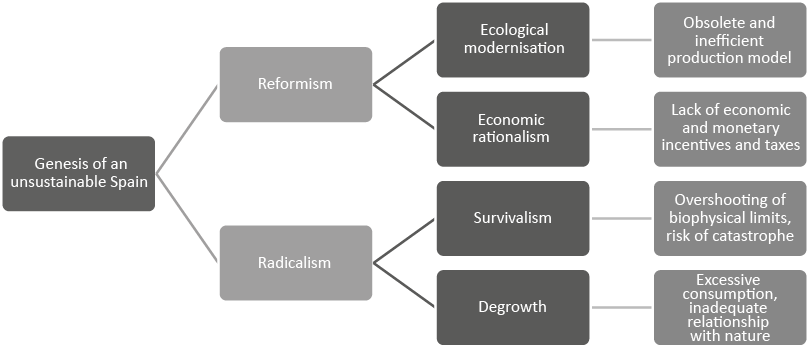

Despite the fact that survivalism would be the ultimate ecological judge of Spanish environmental policies, the ecological transition agenda is dominated by the reformist discourse of ecological modernisation. This is supported by economic rationalism and some degrowth elements, as evidenced by the fact that the transition aims to build a circular economy that respects environmental limits through a robust system of economic incentives, changes in habits of consumption of goods and services, and the gradual dismantling of the construction sector (see Figure 3).

According to the Spain 2050 report, the transition through ecological modernisation revolves around three main axes. The first involves technological replacement by means of investment in innovation and development by both public and private stakeholders. In this way, both public and private capital investment should accelerate the electrification of the economy, enhance the capacity to recycle productive capital, and support the development of renewable energy storage technologies and green hydrogen. This entails replacing petrol and diesel cars with a new fleet of electric cars; strengthening rail transport in all three modes (short-, medium- and long-distance); designing new urban supply and drinking water infrastructures, among others. The second axis involves increasing economic efficiency and the use of resources not only by means of these new technologies and industries, but also through incremental improvements to existing ones. The three principal areas would be the enhancement of energy efficiency in buildings, renewable energy and water use. The document also highlights the “blue economy”, which promotes a more efficient use of marine resources by harnessing offshore wind energy, hydrogen and wave energy, as well as the use of algae to further develop an industry in growing demand. The third axis involves an agenda driven and monitored by a clearly defined system of time-bound targets for resource-use reduction and decarbonisation in each economic sector. This can be done by imposing standards on companies concerning the service life of product components and warranties. Finally, this path to modernisation requires the coordination of different areas of government, most notably environmental and public health policies.

Furthermore, green modernisation is set to benefit from a new green tax system. It will involve: incorporating the negative externalities of carbon dioxide emissions into transport and energy prices; introducing taxation schemes for households, agriculture and services; rapidly reducing European emission allowances to ensure that fewer companies rely on them and to accelerate the decarbonisation of production; and imposing taxes on road and air travel. With regard to the latter, it is recommended that additional taxes be levied on the use of private vehicles, taking into account the individual characteristics of each vehicle (weight, power, emissions); there is also a recommendation for taxes to be levied on frequent air travellers, as well as additional taxes on each ticket. Finally, in order to compensate those on the losing side in this new tax regime, it is proposed that part of the resulting revenue be returned to citizens and specific funds be created to compensate the productive sectors most affected by the transition.

Finally, it should be noted that the document contains a diffuse and even distorted presence of ecomodernist elements. On the one hand, the document calls for greater public participation in technological innovation processes. This commitment to the public sphere is more explicit in ecomodernist discourse than in ecological modernisation discourse, as proponents of the latter place primary responsibility for innovation on the market (see Milanez and Bührs, 2007). However, this ecomodernist imprint diminishes when it becomes clear that the technologies the Spanish government aims to promote are precautionary in nature. This would include renewable energies which, despite being embraced by ecomodernists, are not part of their distinctive proposals. The document also proposes the creation of corridors between vulnerable ecological areas in order to reduce their vulnerability in terms of biodiversity conservation. The creation of these corridors has been emphasised by authors within the ecomodernist sphere (see Ellis, 2015; Marris, 2013).

The presence of the degrowth discourse is not incompatible with the previous two discourses. It can be identified in two complementary areas. One is the restriction of two economic sectors: construction and air transport; the other is the promotion of agro-ecological agriculture and the reduction in consumption of key items. Regarding the former, it is recommended that flights be banned where the equivalent train journey takes less than two and a half hours, along with an implicit recommendation to progressively dismantle the construction sector, based on the assumption that the growth in housing supply and new building in general will shift towards refurbishment and retrofitting to improve the energy efficiency of existing buildings. The latter, for its part, calls for prioritising organic farming and reshaping the moral values of Spanish consumers. This would entail replacing the current ideal of happiness with a shift in the direction of a form of sufficiency centred on maximising the consumption of clothing, electronic devices and meat. This new morality would be partly inspired by the ideal of “good living” advocated by degrowth adherents (see Demaria et al., 2013: 200).

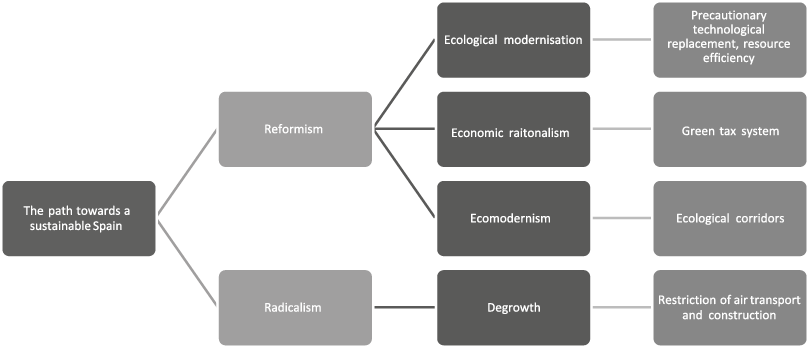

Spain in 2050: efficient, precautionary and less consumerist

The story of Spain in 2050 has a happy, but inconclusive, ending as far as the duty of full sustainability is concerned (see Figure 4). This is because the—more or less definitive—ecological stabilisation would occur towards the end of this century, contradicting the goals agreed upon in the Paris Agreement. According to the Spain 2050 document, the rise in average global temperatures would peak at more than two degrees above pre-industrial levels. This prognosis is an indication of the presence of survivalist discourse, now at the methodological level. Not surprisingly, the description of Spain in 2050 is based on a simulation of mathematical models to depict the future situation, in accordance with the spirit of The Limits of Growth report. The variables analysed were the area of dry land and the number of people who will live in water-scarce areas. This blurs the line between the heuristic presentation of trends and prediction, which takes on an air of inevitability (see Randers, 2012).

According to the document, Spain in 2050 will primarily be the result of ecological modernisation, for the following reasons: it will be an energy-abundant country adopting a precautionary approach; it will have a new productive structure; and it will possess a more efficient and cleaner transport system. Regarding the first area, Spain will have a 100 % renewable energy mix in 2050, thanks to a partnership between the public sector and cutting-edge local companies. These renewables would be dominated by solar photovoltaic energy and, to a lesser extent, wind energy. The development of highly efficient batteries would lead to them being used to generate green hydrogen, a fuel that is suitable for those sectors that are most difficult to decarbonise, including heavy goods transport. By 2050, domestic use of energy (heating, cooking) and private transport in Spain will be largely electrified. In this way, these new industries will have been able to generate new jobs, maintaining sustainable GDP growth.

With regard to the production structure, the circular economy will be a reality thanks to the modernisation of tourism, the agricultural industry and the financial system. The tourism sector will be sustainable due to its highly efficient use of water. This, in turn, will make the agricultural sector more sustainable through the adoption of new irrigation and monitoring systems and the use of more environmentally friendly fertilisers. The financial sector will have injected the capital needed to sustain this new production system. This will be possible because profitable investment in green sectors will become commonplace, even for small or medium-sized enterprises. Eventually, the road transport system will be composed of autonomous electric cars, which will coexist for some time with smaller, more efficient, internal combustion engine vehicles. Aircraft will also become more efficient, following a profound reconversion of this industry; the counterpart will be maritime transport, the decarbonisation of which will take place in Spain in the second half of the 21st century thanks to biofuels and wind and hydrogen propulsion.

On the other hand, the future Spain will be less consumerist after having embraced a new set of moral values. This will be shaped by degrowth discourse, with Spaniards reducing the consumption of meat, clothing and electronic devices, which will lead to greater levels of overall happiness. The document even specifies that the country’s consumption of meat, clothing and electronic devices will be reduced fivefold. Nevertheless, the influence of degrowth is not exclusively linked to decreasing consumption, but also to the way goods are produced and consumed. Hence, degrowth will also be a feature of 2050 Spain, as consumption is expected to become more local, which will affect how industries provide their services: value chains for consumer products will be shorter and simpler; the electronics sector will shift its focus to repair and maintenance; and a robust sub-sector dedicated to custom tailoring and alterations will emerge as demand for new clothing declines. Finally, the Spanish population will travel less by air. In short, less will be more.

The energy and ecological transition is an open challenge at global, national and local levels. Its open-ended nature means that it is shaped by normative principles expressed in discourses, narratives and social imaginaries that are not pre-configured; rather, they are the result of a struggle between different visions of a sustainable and just society. This issue is gaining importance in the European political agenda; not surprisingly, the European Union has been the first region in the world to officially aspire to be a carbon neutral society by 2050. An example of this was the adoption of the European Green Deal, approved just before the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although its place is now less prominent both on the political agenda and in the media, its consequences remain highly relevant. Phenomena such as rising energy prices due to the outbreak of war in Ukraine, farmers’ revolts against the EU’s transition policy and the unconventional action of climate activism should be read in the light of dissatisfaction with national versions of the Green Pact or climate change laws, caused either by political over-ambition or under-ambition. Because of its economic importance in the EU, Spain is one of the main arenas of contention over what the ecological and energy transition will look like. For this reason, analysing the path that Spanish government institutions are taking is an essential task.

This article has made a contribution to this area by interpreting the conceptual and normative assumptions that guide Spanish foresight policy. The Spain 2050 document is the touchstone that will steer subsequent publications. Despite its declining media visibility and the lower status of the public agency responsible for drafting it within the government hierarchy, the document remains highly revealing. It lays out the conceptual assumptions underpinning the current government’s diagnosis of unsustainability. It also sets out the vision needed to prevent ecological collapse, and specifies the social, political, legal, economic and technological measures required to avert it and to build a sustainable and just society. This article has used an argumentative approach and qualitative discourse analysis to identify four imaginaries of ecological transition that guide Spanish foresight policy: ecological modernisation, economic rationalism, survivalism and degrowth. Ecomodernism, the fifth player in this context, serves as a mirror reflecting the implicit assumptions of the Spanish and European sustainability agenda. Its marginal presence makes the others stand out all the more clearly.

The results yielded by the analysis indicate that, in 2050, Spain will be (or might be) more clearly imbued with the discursive paradigm of ecological modernisation prevailing in the European Union’s environmental policy (see Chalaye, 2023; Machin, 2019). This is clear when we look at the sustainable Spain described in the document and the means proposed to achieve it. This forward-looking country is defined by a circular economy (highly efficient in the economic field and in the use of resources for the production of goods and services) and by the success of an energy transition based on renewable energies under precautionary principles in energy innovation. By contrast, the document does not contain the technologies advocated by ecomodernism, namely nuclear fission energy and genetic engineering.

Subsidiarily, Spain in 2050 will be guided by principles of economic rationalism, which is another fundamental element of this sustainable version of the country: building a new green tax system, internalising environmental externalities and taxing polluting activities in line with European countries. Regarding the influence of so-called radical environmental discourses, the presence of survivalism can be seen in how the environmental problem is defined; it is said that Spain must reduce its ecological footprint and learn to live within planetary boundaries after an era of ecological excess. Lastly, degrowth discourse influences key aspects of sustainable Spain, such as the emphasis on changing consumption patterns and the production of goods and services such as meat, electronic devices and clothing. It can also be seen in statements that challenge the statu quo, such as calls to shrink the construction sector or to ban short-haul flights.

These results are an initial foray into the study of Spain’s little-explored energy and ecological transition policy. In particular, there remains the task of analysing its normative and conceptual foundations, without which it is impossible to understand either the problems identified or the solutions proposed to address them. A number of potential avenues for future research can be identified. Firstly, a normative approach can be added to the argumentative one when analysing ecological transition policies. This refers to the second strand of discourse analysis, which focuses on gauging the deliberative quality of the policies under examination and is clearly inspired by Habermasian thought (see Leipold et al., 2019). In this respect, the degree of exclusion of certain discourses in the documents analysed may be a symptom of a lack of deliberative quality in the policies adopted. Secondly, the discursive approach can be applied not only to government documents, but also to the complex network of stakeholders involved in processes prior to the adoption of policies by governments. In this way, an overview of Spanish climate and energy policy could be gained by identifying broader discursive coalitions.

Asafu-Adjaye, John; Blomqvist, Linus; Brand, Stewart; Brook, Barry; Defries, Ruth; Ellis, Erle; Foreman, Christopher; Keith, David; Lewis, Martin; Lynas, Mark; Nordhaus, Ted; Pielke, Roger; Pritzker, Rachel; Ronald, Pamela; Roy, Joyashree; Sagoff, Mark; Shellenberger, Michael; Stone, Robert and Teague, Peter (2015). An Ecomodernist Manifesto. Ecomodernism. Available at: http://www.ecomodernism.org/, access November 12, 2024.

Bardi, Ugo (2020). Before the collapse. A guide to the other side of growth. Berlin: Springer.

Bazilian, Morgan and Pielke, Roger (2013). “Making Energy Access Meaningful”. Issues in Science and Technology, 29(4): 74-78.

Biermann, Frank (2014). Earth System Governance: World Politics in the Anthropocene. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chalaye, Pierrick (2023). “The Discursive Sources of Environmental Progress and Its Limits: Biodiversity Politics in France”. Environmental Politics, 32(1): 90-112. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2022.2034411

Comisión Europea (s. f.a). Strategic Foresight. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/strategic-foresight_en, access March 30, 2025.

Comisión Europea (s. f.b). Foresight: What, Why and How.

Comisión Europea (2024). The Megatrends Hub. Available at: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/foresight/tool/megatrends-hub_en, access March 30, 2025.

Crutzen, Paul and Stoermer, Eugene (2000). “The Anthropocene”. Global Change Newsletter, 41: 17.

Degrowth.info editorial team (2020). Planning for Post-Corona: A Manifesto for the Netherlands. Degrowth.info. Available at: https://degrowth.info/en/blog/planning-for-post-corona, access October 30, 2024.

Demaria, Federico; Schneider, François; Sekulova,

Filka and Martinez-Alier, Joan (2013). “What is Degrowth? From an Activist Slogan to a Social Movement”. Environmental Values, 22(2): 191-215. doi: 10.3197/096327113X13581561725194

Dryzek, John S. (2022). The politics of the earth: Environmental discourses. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (4th ed.).

Dryzek, John S. and Pickering, Jonathan (2019). The Politics of the Anthropocene. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, Erle (2015). “Ecology in an Anthropogenic Biosphere”. Ecological Monographs, 85(3): 287-331. doi: 10.1890/14-2274.1

Ellis, Erle (2018). Anthropocene. A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Georghiou, Luke (1996). “The UK Technology Foresight Programme”. Futures, 28(4): 359-377. doi: 10.1016/0016-3287(96)00013-4

Geus, Marius de (1999). Ecological Utopias. Envisioning the Sustainable Society. Utrecht: International Books.

Gobierno de Finlandia (s. f.). EU-Wide Foresight Network. Available at: https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/foresight-activities-and-work-on-the-future/eu-wide-foresight-network, access March 31, 2025.

Hajer, Maarten (1995). The politics of environmental discourse: Ecological modernization and the policy process. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hajer, Maarten (2006). Doing discourse analysis: Coalitions, practices, meaning. In: M. van den Brink and T. Metze (eds.). Words matter in policy and planning. Discourse theory and method in the social sciences (pp. 65-74). Utrecht: Netherlands Graduate School of Urban and Regional Research.

Hajer, Maarten and Versteeg, Wytske (2005). “A Decade of Discourse Analysis of Environmental Politics: Achievements, Challenges, Perspectives”. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 7(3): 175-184. doi: 10.1080/15239080500339646

Jackson, Tim (2009). Prosperity Without Growth. Economics for a Finite Planet. Earthscan.

Jänicke, Martin (1990). State Failure. The Impotence of Politics in the Industrial Society. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kallis, Giorgos (2011). “In Defence of Degrowth”. Ecological Economics, 70: 873-880.

Kallis, Giorgos; Paulson, Susan; D’Alisa, Giacomo and Demaria, Federico (2020). The Case for Degrowth. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Karlsson, Rasmus (2018). “The High-energy Planet”. Global Change, Peace and Security, 30(1): 77-84.

La Moncloa (2021). Sánchez presenta “España 2050”, un proyecto colectivo para decidir “qué país queremos ser dentro de 30 años”. Available at: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/presidente/actividades/paginas/2021/200521-sanchez-espana2050.aspx, access December 1, 2024.

Leipold, Sina; Feindt, Peter; Winkel, Georg and Keller, Reiner (2019). “Discourse Analysis of Environmental Policy Revisited: Traditions, Trends, Perspectives”. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 21(5): 445-463. doi: 10.1080/1523908X.2019.1660462

Machin, Amanda (2019). “Changing the Story? The Discourse of Ecological Modernisation in the European Union”. Environmental Politics, 28(2): 208-227. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2019.1549780

Marris, Emma (2013). Rambunctious Garden. Saving Nature in a Post Wild World. London: Bloomsbury.

Maslin, Mark (2021). Climate Change: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (4th ed.).

Meadows, Dennis; Meadows, Donella and Randers, Jorgen (1972). The limits to growth: A report for the club of Rome’s project on the predicament of mankind. London: Universe Books.

Milanez, Bruno and Bührs, Ton (2007). “Marrying strands of ecological modernisation: A proposed framework”. Environmental Politics, 16(4): 565-583. doi: 10.1080/09644010701419105

Mol, Arthur; Sonnenfeld, David and Spaargaren, Gert (2009). The Ecological Modernisation Reader. London: Routledge.

Murphy, Joseph (2000). “Ecological Modernisation Editorial”. Geoforum, 31(1): 1-8. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7185(99)00039-1

Oficina Nacional de Prospectiva y Estrategia (ONPE) (2021). España 2050: Fundamental y propuestas para una estrategia nacional de largo plazo. Gobierno de España.

Princen, Thomas (2005). The Logic of Sufficiency. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Randers, Jorgen (2012). 2052: A global forecast for the next forty years. United States: Chelsea Green Pub.

Rees, William and Wackernagel, Mathis (1996). Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth. British Columbia: New Society Publishers.

Reichel, André and Perey, Robert (2018). “Moving Beyond Growth in the Anthropocene”. The Anthropocene Review, 5(3): 242–249.

Röckstrom, Johan; Will Steffen, Will; Kevin Noone, Kevin; Persson, Åsa; Chapin, F. Stuart III; Lambin, Eric; Lenton, Timothy M.; Scheffer, Marten; Folke, Carl; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim; Nykvist, Björn; Wit, Cynthia A. de; Hughes, Terry; Leeuw, Sander van der; Rodhe, Henning; Sörlin, Sverker; Snyder, Peter; Costanza, Robert; Svedin, Uno; Falkenmark, Malin; Karlberg, Louise; Corell, Robert W.; Fabry, Victoria J. and Foley, Jonathan (2009). “Planetary Boundaries: Exploring the Safe Operating Space for Humanity”. Ecology and Society, 14(2). doi: 10.5751/ES-03180-140232

Schreier, Margrit (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. London: Sage Publications.

Simonis, Udo (1987). Ecological modernisation: New perspectives for industrial societies. Friedrich Ebert Foundation. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/112260

Steffen, Will; Richardson, Katherine; Rockström, Johan; Cornell, Sarah E.; Fetzer, Ingo; Bennett, Elena M.; Biggs, Reinette; Carpenter, Stephen R.; Vries, Wim de;Wit, Cynthia A. de; Folke, Carl; Gerten, Dieter; Heinke, Jen; Mace, Georgina M.; Persson, Linn M.; Ramanathan, Veerabhadran; Reyers, Belinda and Sörlin, Sverker (2015). “Planetary Boundaries: Guiding Human Development on a Changing Planet”. Science, 347(6223). doi: 10.1126/science.1259855

Störmer, Eckhard; Bontoux, Laurent; Krzysztofowicz, Maciej; Florescu, Elisabeta; Bock, Anne-Katrin and Scapolo, Fabiana (2020). Foresight – Using Science and Evidence to Anticipate and Shape the Future. In: M. Sienkiewicz and V. Šucha (eds.). Science for Policy Handbook (pp. 128-142). doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-822596-7.00012-7

Symons, Jonathan (2019). Ecomodernism: Technology, Politics, and the Climate Crisis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Toke, David (2011). Ecological Modernization and Renewable Energy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zalasiewicz, Jan (2022). Science: Old and New Patterns of the Anthropocene. In: J. A. Thomas (ed.). Altered Earth. Getting the Anthropocene Right (pp. 21-50). Cambridge University Press.

1 It is beyond the scope of this article to detail which stakeholders form the different discursive coalitions within Spanish ecological transition. Our object of study is governmental foresight policy, not the processes that have shaped it: parliamentary discussions, the political action of stakeholders from civil society, such as activists or members of the scientific community, and so on. Nevertheless, the identification of these stakeholders and their influence on Spanish ecological transition policy is a project that can be carried out by drawing on the findings of this article.

FigurE 1. Hierarchical structure of the coding framework on sustainability discourses in the Spain 2050 report

Source: Author’s own creation using data from La Moncloa (2022).

FigurE 2. Genesis of an unsustainable Spain in the Spain 2050 document

Source: Author’s own creation using data from La Moncloa (2022).

FigurE 3. The path towards a sustainable Spain in the Spain 2050 document

Source: Author’s own creation using data from La Moncloa (2022).

FigurE 4. A sustainable Spain in the Spain 2050 document

Source: Author’s own creation using data from La Moncloa (2022).

RECEPTION: December 19, 2024

REVIEW: March 28, 2025

ACCEPTANCE: May 19, 2025