The Concept and Measurement of Social Autocratisation: A Test in North Africa

and the Middle East

Concepto y medición de la autocratización social:

test en el Norte de África y Oriente Próximo

Guadalupe Martínez Fuentes and Francisco Javier Robles Sánchez

|

Key words Social Attitudes

|

Abstract This article uses the results from the World Values Survey to propose a global Social Autocracy Index in order to identify social autocratisation processes and categorise them according to intensity, nature and context. We found that there was no univocal relationship between social autocratisation, institutional autocratisation and deteriorating levels of security between 2010 and 2022 when applied to North Africa and the Middle East. While Morocco, Turkey and Iraq shared processes of low-intensity social autocratisation that differed both in their nature (comprehensive/partial) and in their institutional and security-related contexts, Egypt underwent a minimal yet significant and comprehensive reduction in the level of social autocracy against a backdrop of institutional autocratisation and declining security levels. |

|

Palabras clave Actitudes sociales

|

Resumen Este artículo propone un Índice de Autocracia Social a escala global, basado en resultados de la Encuesta Mundial de Valores, que permite advertir procesos de autocratización social, así como la categorización de los mismos en virtud de su intensidad, naturaleza y contexto. Aplicado al Norte de África y Oriente Próximo, descubrimos que no existe relación unívoca entre autocratización social, autocratización institucional y deterioro del nivel de seguridad entre 2010 y 2022. Mientras que Marruecos, Turquía e Irak comparten procesos de consolidación autocrática social de intensidad mínima que difieren en su naturaleza (integral/parcial) y contextualización institucional y securitaria, en Egipto acontece una reducción significativa mínima del nivel de autocracia social, de forma integral, y en un contexto de autocratización institucional y empeoramiento del nivel de seguridad. |

Citation

Martínez Fuentes, Guadalupe; Robles Sánchez, Francisco Javier (2026). “The Concept and Measurement of Social Autocratisation: A Test in North Africa and the Middle East”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 193: 113-130. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.193.113-130)

Guadalupe Martínez Fuentes: Universidad de Granada | gmart@ugr.es

Francisco Javier Robles Sánchez: CSIC. Instituto de Estudios Sociales Avanzados | jrobles@iesa.csic.es

As is well-known, vast efforts have been made to date to define, measure and explain the autocratic drift of political institutions on a comparative and global scale (Knutsen et al., 2024). Interestingly, this significant advance in knowledge has not been accompanied by commensurate substantial progress in the understanding of the social dimension of autocratisation processes. We argue whether or not the world is experiencing a “third wave of autocratisation” that affects institutions (Lührmann and Lindberg, 2019) without defining, measuring or understanding—at a similarly broad scale—the autocratic attitudes within societies affected by the symptoms and consequences of such a wave, or how they have evolved.

Are citizens allowing themselves to be carried along by this type of institutional change, mirroring a shift towards autocracy, or are they resistant, or even reactive to it? We lack sufficiently robust empirical evidence to answer this question, as society has thus far not been addressed in autocratisation studies (Tomini, 2024), and the limited tools available for comparative analysis have been considered “methodologically problematic”1 (De Miguel and Martínez-Dordella, 2014: 103). Unless some answers are obtained in this area, we can only poorly gauge whether the advancing wave can be stemmed and/or reversed.

This paper aims to contribute to filling this knowledge gap by focusing on the processes of social autocratisation. To this end, it offers a new conceptual and operational approach that allows state-level and global trends in society’s autocratic attitudes to be compared, categorising them according to their direction, intensity, nature and contextual framework.

Our model was put to the test by looking at the evolution of attitudes in Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) societies between 2010 and 2022. The choice of this region was due to two factors. First, no other region has such a high concentration of authoritarian regimes. According to the most recent edition of the Bertelsmann Political Transformation Index (BPTI)2, 17 out of its 18 countries have adopted an autocratic rule. Second, there is a significant knowledge gap regarding the evolution of autocratic attitudes in the region, since most opinion surveys have concentrated on understanding predispositions towards democracy (Tessler, 2002, 2007; Tessler and Gao, 2005; Jamal and Tessler, 2008; Tessler, Jamal and Robbins, 2012; Benstead, 2018; Teti, Abbott and Cavatorta, 2019; Kilavuz and Sumaktoyo, 2020; Lindstaedt, 2021, among others), or on levels of satisfaction with or support for government performance (Ciftci, 2018; Williamson, 2021). The time period of analysis was selected for two different reasons. The first is the prominence of the institutional autocratisation process observed in this area (Szmolka and Cavatorta, 2024). The second is the tension unleashed between this institutional drift and the massive social protests in this cycle, interpreted by some as a second wave of “Springs” (Desrues and García Paredes, 2019; Fahmi, 2019; Pérez Beltrán, 2023)3.

This study is structured into four further sections. We next detail the theoretical and operational concepts of our measurement tool. This is followed by a section which discusses its methodology and sets out its application to the universe of MENA countries. The results are presented in the following section. This last section highlights the main conclusions of the study, its contribution to research on this social phenomenon and the future avenues of development, including in case studies, area studies and global studies.

Revisiting the hypothesis posed by Huntington (1991) that there is a “reverse wave” of democratisation under way has sparked debate over the very concept of autocratisation, which has largely focused on political regimes (Croissant and Tomini, 2024). However, there is some consensus around the relevance of a minimal procedural definition, centred on the direction of the institutional political change involved in this process, the institutional arenas in which it manifests and the extent of its consequences (Tomini, 2024).

The ideas proposed by Cassani and Tomini (2018) are the key reference point for this conceptual logic. They envisage institutional autocratisation across three areas governing the allocation and exercise of political power. One concerns political participation in the government selection process. Another is public contestation, which refers to having the opportunity to publicly oppose and criticise the government’s conduct and compete to replace it. The third relates to the limitation of executive power and the protection of individual and civil liberties. Cassani and Tomini used this framework to define the autocratisation of institutions as a political change:

That makes politics increasingly exclusive and monopolistic, and political power increasingly repressive and arbitrary. Executive constraints, civil and individual liberties and political rights weaken, whereas government selection turns less competitive and less participatory (Cassani and Tomini, 2018: 278).

We adopted these authors’ minimal and procedural approach to conceptual formulation, which is widely accepted in institutional studies to define the social variant of the autocratisation process: a positive definition of the concept; an emphasis on the direction of political change; a multidimensional understanding of that change; and a clear delimitation of its expression and scope. From this perspective, we understand social autocratisation4 as an increase in citizens’ predisposition to accept a more arbitrary and repressive exercise of political power and a restriction of space for both public contestation and political participation in the process of government selection.

The second step was to reduce the level of abstraction in the definition, while preserving the features of the concept’s configuration for empirical application purposes. We drew inspiration from the four-indicator operational model proposed by Levitsky and Ziblatt (2018) to detect processes of autocratisation in the attitudes of governing political elites in democratic contexts. Our strategy was to adapt it to the study of the autocratic attitude of citizens in any type of political regime.

In Levitsky’s and Ziblatt’s original model, the first indicator was the expression of “rejection of (or weak commitment to) democratic rules of the game”, which consists of seeking to undermine the legitimacy of elections, among other issues. This is framed within the institutional manifestation of autocratisation that specifically addresses the dimension concerning the regulation of political participation through elections, as proposed by Cassani and Tomini. When this indicator is transferred to our conceptual framework for defining social autocracy, it concerns the feature of having a “social predisposition to accept restrictions to political participation in the process of selecting the government”. In our operational model, we interpret this as an increase in the percentage of the population that shares a negative assessment of the system of democratic election of government and an appreciation of alternative systems.

Levitsky and Ziblatt’s second indicator was the “denial of the legitimacy of political opponents”, which entails disparaging political rivals as criminals and/or claiming they are a threat to national security. This indicator was framed within the institutional manifestation of autocratisation that concerns Cassani and Tomini’s feature of the regulation of public contestation. In terms of our conceptual delimitation of social autocracy, this indicator relates to the “social predisposition to accept the restriction of space for public contestation”. Within our operational model, this indicator is interpreted as an increase in the percentage of the population that shares disinterest in or rejection of the recognition and protection of the work of the opposition.

Levitsky and Ziblatt’s third indicator is the “toleration or encouragement of violence”, which is concerned with fostering violent attacks against the opposition or failing to condemn such forms of aggression. This indicator falls within the dimension regarding the repressive exercise of power, as part of the concept of institutional autocratisation suggested by Cassani and Tomini. In our concept of social autocracy, this describes a social predisposition to accept the repressive exercise of political power. Within our operational model, this indicator is interpreted as an increase in the percentage of the population that shares the idea that resorting to violence is justified.

Levitsky and Ziblatt’s final indicator is the “readiness to curtail civil liberties of opponents, including media” by promoting laws or measures that curtail their room for manoeuvre. This indicator falls within the arbitrary exercise of political power dimension of Cassani and Tomini’s concept of institutional autocratisation. In our conceptual definition of social autocracy, this indicator corresponds to a “social predisposition to accept the arbitrary exercise of political power”. In our operational model, it refers to the increase in the percentage of the population that shares acceptance of laws and measures that restrict civil liberties, both in general terms and in the particular case of the political opposition and media critical of the government.

The third step was to identify possible forms in which social autocratisation may manifest by determining which traits of our concept operate as drivers in the process. To this end, we drew on well-established benchmarks from social and political psychology designed to measure predispositions that predict social support for anti-democratic policies, highlighting two key dimensions5. These are “authoritarian aggression” and “authoritarian submission” (Duckitt et al., 2010; Dunwoody and Funke, 2016; Feldman, 2020). Authoritarian aggression is related to a “social predisposition to accept the repressive exercise of political power”. In turn, authoritarian submission, understood as the appreciation and prioritisation of the order established by authority, is associated with a “social predisposition to accept the restriction of political participation in the government selection process, social predisposition to accept the arbitrary exercise of political power”, and “social predisposition to accept the restriction of space for public contestation”. Within this framework, two types of social autocratisation processes can be identified: partial processes, driven mainly by an increase in attitudes favouring authoritarian aggression or an increase in attitudes favouring authoritarian submission; and full processes, characterised by increases in both types of attitudes.

The last step in our process entailed identifying types of social autocratisation according to the characteristics of the context in which they occurred, following the distinction of institutional autocratisation phenomena proposed by Lührmann and Lindberg (2019: 1099-1100). They used the categories “democratic recession” (when the behaviour of institutions adopts autocratic patterns in democratic situations); “autocratic consolidation” (when the behaviour of institutions moves deeper into autocratic territory in already hybrid or authoritarian situations); and “democratic breakdown” (when the behaviour of institutions adopts autocratic patterns in the transition from a democracy to an autocracy). We identified three forms of social autocratisation within our conceptual framework. When this occurs in hybrid or authoritarian contexts, we speak of “autocratic social consolidation”. We refer to “social democratic recession” if the process occurs in democratic contexts. If this takes place in contexts of transition from democracy to autocracy, we define it as “social democratic breakdown”.

This framework has many advantages. The first is the alignment of the theoretical foundations underpinning the autocratisation of institutions and individual attitudes, which enables the comparative analysis of both trends. The second is its sensitivity to the multidimensional nature of social autocratisation processes, allowing for the distinction between processes prompted by different drivers. The third is its elasticity, which means that it can be applied in different political contexts.

Measuring Social Autocratisation

Our proposal for identifying and classifying trends in social autocratisation involves observing the behaviour of a composite indicator of our own design, which we have called the Social Autocracy Index (SAI). Our operational definition of social autocratisation is the substantial increase in the SAI between two consecutive points in time.

The four indicators proposed in the previous section were used as the basis for the SAI. The data were drawn from successive waves of the World Values Survey (WVS).

The indicator “rejection of or low commitment to democratic rules” (DR) was measured using a question that asked respondents to rate various political systems as forms of government for their own country on a scale ranging from very poor to very good. We took four response components that referred, respectively, to forms of government consisting of “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections”6, “having experts, not government, make decisions according to what they think is best for the country”7, “having the army rule”8 and “having a democratic political system9”. We interpreted those responses in which individuals rated the three authoritarian models of political system as good or very good, and those in which individuals rated the democratic model as bad or very bad as a rejection of democratic rules. The value of the indicator was obtained by calculating the arithmetic mean of the percentage of responses that rated the three authoritarian alternatives as good or very good and the democratic alternative as bad or very bad. This data point was then normalised on a gradient from 0 to 1, where 0 meant an absence of autocratic attitudes and 1 extremely high autocratic attitudes.

To measure “denial of the legitimacy of political opponents” (DL) we used the percentage of respondents who prioritised “maintaining order in the nation”10 over other goals related to the defence of freedoms as a proxy indicator. Its appropriateness lay in the fact that it is associated with the authoritarian value “submission to authority” (Duckitt et al., 2010; Dunwoody and Funke, 2016; Feldman, 2020). This data point was then normalised on a gradient from 0 to 1, where 0 meant an absence of autocratic social attitudes and 1 extremely high social autocratic attitudes.

We measured “toleration or encouragement of violence” (V) by looking at respondents’ views on the possible justification of violence against other people, on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 meant that violence is never justifiable and 10 meant that violence is always justifiable11. This indicator captured the value “authoritarian aggression” (Stenner, 2005; Duckitt et al., 2010; Dunwoody and Funke, 2016). We assumed that those who selected response options between 5 and 10, indicating that they considered violence justifiable, would also be more likely to tolerate or support it. We calculated the percentage of responses between 5 and 10 and normalised the data point on a gradient from 0 to 1, where 0 means an absence of autocratic social attitudes and 1 extremely high autocratic social attitudes.

To measure the indicator “readiness to curtail civil liberties of opponents, including media” (CL), we used as a proxy the rating of the importance of living in a country that is governed democratically12 on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 meant “not at all important” and 10 meant “absolutely important”. We considered that those who opted for response categories 1 to 5 would be more likely to support laws and measures that restricted civil liberties, both in general terms and in the particular case of the political opposition and media critical of the regime. This would represent an attitude opposed to that derived from “emancipative values” or “self-expression values” (Welzel, 2010; Welzel, 2021; Teti, Abbott and Cavatorta, 2019). We counted the percentage of responses in these categories and normalised the data point on a gradient from 0 to 1, where 0 meant an absence of autocratic social attitudes and 1 meant extremely high autocratic social attitudes.

The aggregate value of the SAI was expressed on a continuous scale from 0 to 1, where 1 meant the highest level of social autocracy and 0 the lowest.

Two solutions were employed to obtain the aggregate value. The first related to the use of weighting. Equal weighting was given to the four indicators, as there was no theoretical or empirical basis to suggest otherwise13. The second solution concerned the formula for aggregating the value of the four indicators. A geometric aggregation calculation was chosen for this purpose because it is more sensitive than linear aggregation for distinguishing between contexts where the indicators yield similar values and cases where extreme values offset one another. Thus, the formulation of the SAI for a given point in time (t) is expressed as the fourth root of the result of multiplying the values of the four indicators at that point in time:

Table 1 provides a systematic overview of the key elements of the SAI.

The variation of the SAI between two points in time ranged from 1 to -1. A variation of 1 indicates the maximum intensity of the autocratisation process, namely the difference between a wave of the WVS in which the SAI recorded a value of 0 and the subsequent wave in which it recorded a value of 1. Conversely, a variation of -1 reflects the maximum regression of the SAI, corresponding to the difference between a wave with an SAI value of 1 and the subsequent wave in which the value returned to 0. For analytical purposes, we regarded a substantial increase in SAI as a positive change equal to or greater than 0.09, this cut-off point being deemed to be high enough to rule out inconsequential changes, but low enough to capture significant changes14. By the same logic, we considered a substantial reduction to be one that reached the minimum value - 0.09. Decreases and increases that did not reach the preset minimum values were interpreted as a pattern of stability.

The four main merits of our proposal are outlined below. The first is its quality as a measurement tool, according to the validity requirements in terms of both content and data generation process (McMann et al., 2022). The validity of its content stems from the ability to reflect the essential elements of our theoretical and operational concept of social autocratisation. The data generation process is valid because the data come from a single source, accepted as an impartial data manager, which provides reliable information. The second merit is the relative simplicity of calculating both the SAI and its variation over time, which allows for easy replication, within the availability range of WVS waves 15. The third lies in its usefulness for identifying different manifestations of social autocratisation processes, based on the nature of the social attitudes driving them, their intensity and the context in which they arise. The fourth merit is its versatility to adapt to research interests that go beyond the identification of general trends, as the SAI makes it possible to segment observation for specific socio-demographic profiles identifiable based on the cross-referencing of variables collected in the WVS.

MENA countries as the universe of application

of the SAI

While at the end of the twentieth century experts identified institutional processes of democratisation in other areas of the world, in the MENA region they pointed to the “persistence” or “resilience” of a resistant authoritarianism, given the failure of some timid experiences of political liberalisation (Bellin, 2004; Brumberg, 2002; Entelis, 2008; Hinnebusch, 2006; Myers, 2010). However, an extraordinary wave of social protests in early 2011 revealed that these societies aspired to dismantle the authoritarian political regime model and to secure respect for their civil rights and liberties, among other demands (Álvarez-Ossorio, 2013: 18). These protests prompted a bout of heterogeneous institutional political change, including the foundation of democratic regimes, political liberalisation, the establishment of new forms of authoritarianism and merely cosmetic reforms of some authoritarian regimes (Szmolka, 2013). Some warned that the predominant form of institutional change likely to emerge in the region would be a form of authoritarianism that was darker, more repressive, more sectarian and even more deeply resistant to democratisation than in the past. Subsequent developments have proved them right: six of the seven indicators that make up Freedom House’s freedom index have recorded significant declines in the region, four of them representing the sharpest global setbacks16 (Freedom House, 2022: 14).

Nevertheless, there is a reasonable doubt as to whether or not such processes of institutional autocratisation have been accompanied by processes of social autocratisation. Two arguments have been adduced to support this possibility. Cammet, Diwan and Vartanova (2020) have shown that prolonged instability and increased perceived insecurity in the countries of the region in this period have helped to promote attitudes in public opinion that are more reticent to accept democracy as a system of government. In addition, Barreñada (2023) warned of the gradual establishment of new forms of authoritarianism in the area, such as the movement known as “technocratic populism” or “technopopulism”, the success of which has been attributed to the existence of a social majority with autocratic attitudes (Storm, 2023: 81). These attitudes are passivity and demobilisation in the face of the gradual erosion of institutional checks and balances and the vilification of opponents as foreign agents and enemies of the people; reliance on technocrats to stifle opposition; and the veneration of a saviour leader who is above the law.

This paper compares the SAI results in waves 6 and 7 of the WVS in the region (periods 2010-2014 and 2017-2022, respectively) to shed light on this dilemma by answering three research questions: 1) Were there any processes of social autocratisation in the region between 2011 and 2022? If so, 2) did they share the same nature and level of intensity, or were they different in these respects? and 3) Did they represent identical or different manifestations depending on the characteristics of their respective contexts?

The complete universe of cases participating in both waves 6 and 7 of the WVS was selected. The countries chosen were Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Turkey. Wave 6 WVS surveys were conducted in Morocco and Turkey in 2011; in Egypt, Lebanon, Tunisia and Iraq in 2013; and in Jordan and Libya in 2014. Wave 7 took place in Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and Turkey in 2018; in Tunisia in 2019; in Morocco in 2021; and in Libya in 202217.

Despite its limited size, the universe encompassed a vast multiplicity of contexts. These countries have a variety of systems of government (republics and monarchies) and political economies (oil-poor and oil-rich). They were also representative of different institutional responses to the wave of social protests that took place at the beginning of the last decade. A distinction can be made between cases where social uprisings were more far-reaching and ushered in a transition to democracy (Tunisia, Egypt and Libya); cases where they led to processes of political liberalisation (Jordan and Morocco); and cases where they had less or no impact (Iraq and Lebanon), or none at all (Turkey). The first group also included cases where the transition to democracy was reasonably successful (Tunisia) and cases where it was thwarted very early on (Egypt and Libya). For their part, Morocco, Turkey, Tunisia and Egypt were scenarios where technocratic populism has only taken root more or less recently, compared to the rest of the countries (Barreñada, 2023; Storm, 2023).

Our universe likewise encompassed a set of stability/change patterns in the level of institutional autocracy between the first and second waves of the WVS. Szmolka and Cavatorta (2024: 2022) identified three patterns for the growth of autocratic developments: one that occurs within hard-line autocracies; one that occurs within moderate autocracies; and one that causes the transition from a moderate autocracy to a hard-line autocracy. Following the measurement system devised by Szmolka and Cavatorta, two of these modalities were included in our universe: Libya exemplified the first type, while Morocco and Egypt epitomised the third type. Other studies which used different metrics applied to alternative databases also placed Turkey within the pattern of institutional autocratisation associated with regime change. Freedom in the World (Freedom House, 2023: 12) pointed to Turkey’s transition from a partly free to a not free state as one of the most notable declines of the last decade. Boese et al. (2022) also identified Turkey as one of the countries where the process of institutional autocratisation has had the greatest impact in recent times, based on the evolution of the Liberal Democracy Index produced by Varieties of Democracy.

Different levels of security were found for our universe in both waves of the WVS, as well as two trends in these two waves, according to the Global Peace Index18. In Wave 6, Jordan and Tunisia had a high level of security compared to Egypt, Morocco and Libya, which had a medium level; Turkey and Lebanon, which had a low level; and Iraq, which had a very low level of security. In Wave 7 there were no high-security cases, and the number of cases with a very low level of security tripled. Jordan and Tunisia saw their levels downgraded to medium secure; Egypt and Turkey also experienced a decrease in their security; Egypt dropped to a low level; and Turkey saw a reduction to a very low level of security. The most pronounced change was that which occurred in Libya, as it went from medium to very low security levels. Only Morocco, Lebanon and Iraq shared the trend of stability.

This diversity of contexts and trends of stability/change in the institutional and security arenas gave reason to expect:

- H1: Social autocratic consolidation processes in countries where institutional autocratic consolidation or a deterioration in security levels have also taken place (such as Turkey, Libya, Egypt, Morocco and Jordan).

- H2: More intense social autocratisation levels in countries where processes of institutional autocratic consolidation and a deterioration in the level of security have overlapped (such as in Libya and Turkey).

- H3: A process of social democratic recession associated with a deterioration in the level of security (Tunisia).

- H4: An absence of social autocratisation processes where patterns of institutional stability and/or security level stability have been identified (such as Lebanon and Iraq).

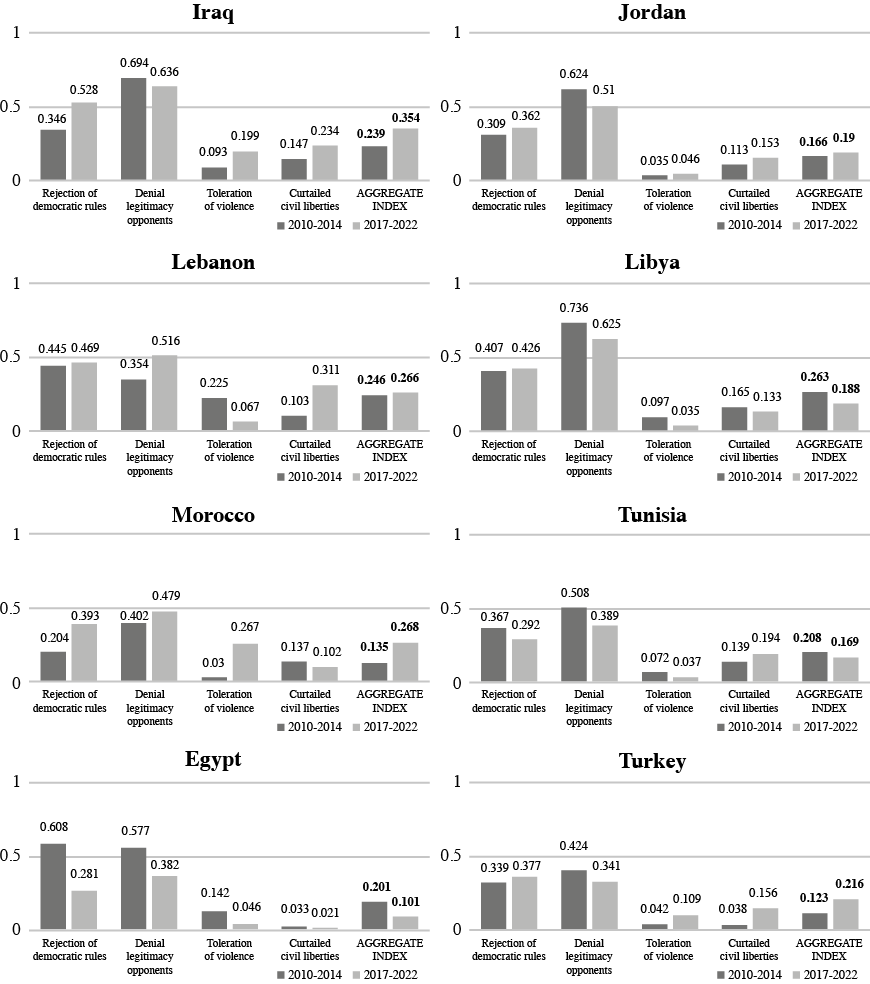

Table 2 shows the results of the SAI observation in Waves 6 and 7 of the WVS in the region (covering the periods 2010–2014 and 2017–2022, respectively), as well as the variation between the two Waves. Figure 1 is provided as a supplement for a better overview of the heterogeneous social dynamics of the region over this time period.

The SAI in Wave 6 of the WVS indicates that Lebanon, Egypt, Libya, Iraq and Jordan were the cases with the highest level of social autocracy (0.3 for Lebanon and above 0.2 for the rest). In Wave 7, however, Iraq and Morocco exceeded 0.3; Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey were in the 0.2 range; and only Egypt and Tunisia were at a lower level.

Three patterns can be identified in the variation of the SAI in this period. One is its significant positive change in Morocco (0.131), Iraq (0.114) and Turkey (0.095). Another pattern is a significant negative change in Egypt (-0.094). The third is a logic of stability in the remaining cases.

The shared feature between the social autocratisation processes in Morocco, Iraq and Turkey is that they are all examples of social autocratic consolidation of minor intensity. However, they differ in their context and nature. While the Moroccan and Turkish processes of social autocratisation took place within the context of a transition towards a more severe model of institutional autocracy, the process in Iraq unfolded within a framework of continuity of the existing regime model. In addition, whereas Moroccan and Iraqi social autocratisation took place against a backdrop of unchanged security, Turkey’s occurred in a situation of deteriorating security levels. Moreover, while Morocco and Iraq epitomised comprehensive social autocratisation, Turkey experienced only partial social autocratisation. Moroccan and Iraqi social autocratisation was driven by a significant increase in the value of indicators associated with acceptance of restricted political participation in the government selection process and the repressive exercise of political power. That is, an increase in both authoritarian submissive attitudes and authoritarian aggression. In the case of Morocco, this second aspect was particularly noticeable, given the sharp increase in the percentage of the population that shared the belief that resorting to violence was justified (24 %). Instead, Turkish social autocratisation was due to a significant increase in the social predisposition to accept the arbitrary exercise of political power, which represented a spread of attitudes associated only with authoritarian submission.

The notable decline in the Egyptian SAI was marked by its low level of intensity (–0.11) and by a significant negative shift in social predisposition towards accepting restrictions to political participation in the government selection process (a 33 % decrease) and the repressive exercise of political power (a 9 % decrease). Thus, Egypt experienced a regression from comprehensive social autocracy, characterised by a reversal in attitudes associated with both authoritarian submission and authoritarian aggression. The context for this social change was a process of institutional autocratic consolidation, involving a transition from a moderate autocracy to a hard-line autocracy, alongside a deterioration in the level of security.

The first reason why these findings are particularly valuable is that they disprove all of our working hypotheses. Processes of social autocratisation are not necessarily more intense in countries where institutional autocratisation and/or the deterioration of security levels are more pronounced, as demonstrated by the cases of Libya and Egypt (H2). Such institutional and security drifts are not uniquely linked to social autocratic consolidation trends (H1), as shown by the stability of social autocracy in the Libyan and Jordanian cases; nor are they solely associated with social democratic recession trends (H3), as evidenced by the stability of social autocracy in the Tunisian case. The absence of institutional and security changes did not clearly correlate with SAI stability either (H4), as this state of affairs did not prevent Iraqi social autocratisation.

The second noteworthy aspect was the finding that the significant trends of change in the SAI for Morocco, Iraq, Turkey and Egypt did not permit the identification of a clear pattern of relationship between stability/change in social attitudes and stability/change in institutional and security systems. The contextual conditions surrounding the decline in the level of Egyptian social autocracy—namely institutional autocratisation resulting in a change in the authoritarian model and a deterioration in security—were also present in Turkey, but with the opposite outcome. The outcome observed in the Turkish case was also seen in Morocco and Iraq; however, while Morocco experienced a deterioration in its security situation, this condition was absent in the other two cases.

The third valuable aspect in our results lies in two key findings. One is that the significant reversal of two factors represents a driver of social change in the direction towards less social autocracy (Egypt). These factors were the social predisposition to accept: the repressive exercise of political power; and the restriction to political participation in the government selection process. Both jointly articulate the comprehensive expression of the attitude change model associated with the authoritarian submission/authoritarian aggression pair. Another valuable finding is that the significant increase in social autocracy did not require the simultaneous occurrence of a significant advance of both factors. The results for the Turkish, Iraqi and Moroccan cases show that there were processes of social autocratisation that were only partially driven by different factors.

This paper has presented a new conceptual proposal of social autocratisation for comparing trends in society’s autocratic attitudes at both state and global levels. These attitudes can be distinguished by their direction, intensity, nature and contextual framework. Three arguments support its relevance: i) its theoretical grounding in the study of institutional autocratisation and individuals’ attitudes; ii) its ability to understand the multidimensional nature of the process; and iii) its flexibility, which makes it suitable for use across different regime types and models of regime change. The accompanying operationalisation adopts a quantitative approach that boasts three main additional advantages: i) the validity of both its content and data generation process; ii) its ease of calculation; and iii) its versatility in capturing dynamics of increase, stability or decline in the level of social autocracy, both within society at large and among specific social sectors.

By applying it to the MENA countries between 2010 and 2022, we have provided a doubly valuable input for political studies in the area. On the one hand, our findings discourage both the understanding that there is a widespread social autocratic drift and the illusion of a predominant resilience of pro-democratic attitudes. On the other hand, they encourage further research along at least three main avenues. One is the in-depth critical case study of the path of dependency leading to change in Egyptian, Moroccan, Turkish and Iraqi autocratic social attitudes. The second avenue is a qualitative comparative analysis for explanatory purposes, aimed at identifying the likely complex and multicausal factors behind the divergent trends in the region. The third avenue is concerned with addressing the open question of whether the increase, decrease and stability of autocratic attitudes manifested at the aggregate social level represent patterns shared by society as a whole, or whether they are particularly intense among certain groups or cohorts. Identifying who has autocratic leanings, to what extent and how they think in autocratic terms is a prerequisite for understanding why these attitudes have evolved, as well as for anticipating their consequences for the stability of their respective governments and regimes.

Our results also contribute to the general development of this field of knowledge on a global scale, by challenging some theses and pointing to other dilemmas to be addressed in future studies. First, our findings problematise the relationship that social autocratisation has with concurrent processes of institutional autocratisation and the deterioration of state security levels. The open question is whether the MENA area is an exception in this respect as well, and the answer lies in future inter-area studies. Second, by demonstrating that social autocratisation processes in this region are different in nature, we invite researchers to engage in comparative global analyses to determine whether this heterogeneity constitutes a dominant pattern or not. Third, our results are encouraging in terms of investigating the possible relationship between processes of social autocratisation and the establishment of different types of authoritarian populist governments. While we are familiar with the institutional, political and economic conditions that lead to such forms of government to be established in various regions of the world (Weyland, 2024), little has been explored regarding whether there are also some societal prerequisites, such as social autocratisation itself.

The application of our conceptual and measurement tool for social autocratisation would also enable scholars to connect this field of study with parallel research on other social attitudes of equal concern to democracy advocates in the future. These include “pernicious polarisation”, understood as mutual social distrust between Us and Them that encourages support for undemocratic actions (Somer, McCoy and Luke, 2021).

Finally, extending the temporal, geographical and disciplinary scope of application of this new tool is a highly promising endeavour in order to further our understanding of the relationship between the individual component of authoritarian aggression and submission attitudes, and the macro-level dimension of social autocratisation processes. This challenge is an invitation to adopt an approach that can articulate complementary approaches of comparative political, sociological and psychosocial analysis, both necessary and underexplored to date.

The future of studies on autocratisation processes lies in recognising and overcoming the current limitations of this field of research by diversifying its empirical benchmarks, shifting attention beyond institutions and the political actors that govern them (Croissant and Tomini, 2024), and linking them to other components of the system. This study takes an initial step in that direction, considering citizens not only to be actors primarily affected by the political processes of institutional autocratisation, but also key players in the concomitant social process, whether aligned with or divergent from the former processes. We hope that the conceptual and analytical tool presented here will be useful in taking the necessary next steps to identify the early symptoms, causes, counterweights and societal consequences of the current drifts of democratic recession, democratic breakdown and autocratic consolidation of political regimes.

Álvarez-Ossorio, Ignacio (ed.) (2013). Sociedad civil y contestación en Oriente Medio y Norte de África. Barcelona: Cidob.

Barreñada, Isaías (2023). “Tecnopopulismo autoritario en los países árabes y legitimación internacional”. Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, 135: 29-52. doi:10.24241/rcai.2023.135.3.29

Bellin, Eva (2004). “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective”. Comparative Politics, 36(2): 139-157. doi: 10.2307/4150140

Benstead, Lindsay J. (2018). “Survey Research in the Arab World: Challenges and Opportunities”. PS: Political Science & Politics, 51(3): 535-542. doi: 10.1017/S1049096518000112

Boese, Vanessa. A.; Lundstedt, Martin; Morrison, Kelly; Sato, Yuko and Lindberg, Staffan I. (2022). “State of the World 2021: Autocratization Changing its Nature?”. Democratization, 29(6): 983-1013. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2022.2069751

Brumberg, Daniel (2002). “Democratization in the Arab World? The Trap of Liberalized Autocracy”. Journal of Democracy, 13(4): 56-68. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0064

Cammet, Melani; Diwan, Ishac and Vartanova, Irina (2020). “Insecurity and Political Values in the Arab World”. Democratization, 27(5): 699-716. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2020.1723081

Cassani, Andrea and Tomini, Luca (2018). “Reversing Regimes and Concepts: From Democratization to Autocratization”. European Political Science, 19: 272-287. doi: 10.1057/s41304-018-0168-5

Ciftci, Sabri (2018). “Self-expression Values, Loyalty Generation, and Support for Authoritarianism: Evidence from the Arab world”. Democratization, 25(7): 1132-1152. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2018.1450388

Croissant, Aurel and Tomini, Luca (2024). Introduction. In: A. Croissant and L. Tomini (eds). The Routledge Handbook of Autocratization. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003306900

De Miguel, Jesús M. and Martínez-Dordella, Santiago (2014). “Nuevo índice de democracia”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 146: 93-140. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.146.93

Desrues, Thierry and García de Paredes, Marta (2019). “Political and Civic Participation of Young People in North Africa: Behaviours, Discourses and Opinions”. Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos, 26: 1-22. doi: 10.15366/reim2019.26.001

Duckitt, John; Bizumic, Boris; Krauss, Stephen W. and Heled, Edna (2010). “A Tripartite Approach to Right-wing Authoritarianism: The Authoritarianism-conservatism-traditionalism Model”. Political Psychology, 31(5): 685-715. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2010.00781.x

Dunwoody, Philip and Funke, Friedrich (2016). “The Aggression-Submission-Conventionalism Scale: Testing a New Three Factor Measure of Authoritarianism”. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 4(2): 571-600. doi:10.5964/jspp.v4i2.168

Entelis, John P. (2008). Entre los deseos democráticos y las tentaciones autoritarias en el Magreb Central. In: Y. H. Zoubir and H. A. Fernández (coords.). El Magreb. Realidades nacionales y dinámicas regionales, (pp. 37-61). Madrid: Síntesis.

Fahmi, Georges (2019). “What’s New about this Second Wave of Arab Uprisings?”. Middle East Directions Blog. Available at: https://blogs.eui.eu/medirections/whats-new-second-wave-arab-uprisings/, access July 7, 2025.

Feldman, Stanley (2020). Authoritarianism, Threat, and Intolerance. In: Eugene Borgida; Christopher M. Federico and Joanne M. Miller (eds.). At the Forefront of Political Psychology. Essays in Honor of John L. Sullivan. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780429351549

Freedom House (2022). Freedom in the Word 2022. The global expansión of authoritarian rule. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/2022/global-expansion-authoritarian-rule, access July 7, 2025.

Freedom House (2023). Freedom in the Word 2023. Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy. Available at: https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/FIW_World_2023_DigtalPDF.pdf, access July 7, 2025.

Heydemann, Steven (2013). “Tracking the ‘Arab Spring’: Syria and the Future of Authoritarianism”. Journal of Democracy, 24(4): 59-73. doi: 10.1353/jod.2013.0067

Hinnebusch, Raymond (2006). “Authoritarian Persistence, Democratization Theory and the Middle East: An Overview and Critique”. Democratization, 13(3): 373-395. doi: 10.1080/13510340600579243

Huntington, Samuel P. (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman and London: University of Oklahoma Press.

Jamal, Amaney and Tessler, Mark A. (2008). “The Democracy Barometers (Part II): Attitudes in the Arab World”. Journal of Democracy, 19(1): 97-111.

Kilavuz, M. Tahir and Sumaktoyo, Nathanael G. (2020). “Hopes and Disappointments: Regime Change and Support for Democracy after the Arab Uprisings”. Democratization, 27(5): 854-873. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2020.1746766

Knutsen, Carl H.; Marquardt, Kyle L.; Seim, Brigitte; Coppedge, Michael; Edgell, Amanda B.; Medzihorsky, Juraj; Pemstein, Daniel; Teorell, Jan; Gerring, John and Lindberg, Staffan I. (2024). “Conceptual and Measurement Issues in Assessing Democratic Backsliding”. PS: Political Science & Politics, 57(2): 162-177. doi: 10.1017/S104909652300077X

Levitsky, Steven and Ziblatt, Daniel. (2018). How democracies die. New York: Crown.

Lindstaedt, Nathasha (2021). Democratic Decay and Authoritarian Resurgence. Bristol: University Press.

Lührmann, Anna and Lindberg, Staffan I. (2019). “A Third Wave of Autocratization is Here: What is New about It?”. Democratization, 26(7): 1095-1113. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029

McMann, Kelly; Pemstein, Daniel; Seim, Brigitte; Teorell, Jan and Lindberg, Staffan I. (2022). “Assessing Data Quality: An Approach and an Application”. Political Analysis, 30(3): 426-449. doi: 10.1017/pan.2021.27

Moreno-Álvarez, Alejandro and Welzel, Christian (2014). Enlightening people: The spark of emancipative values. In: R. J. Dalton and C. Welzel (eds.). The civic culture transformed: From allegiant to assertive citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Myers, Ralph (2010). Persistence of Authoritarianism in the Middle East and North Africa Rentierism: a paradigm in distress? Munich: Grin Verlag.

Pérez Beltrán, Carmelo (ed.) (2023). Dinámicas de protestas en el mundo árabe. Desafiando los regímenes autoritarios. Granada: Editorial de la Universidad de Granada.

Przeworski, Adam (2024). “Who Decides What Is Democratic?”. Journal of Democracy, 35(3): 5-16. doi: 10.1353/jod.2024.a930423

Somer, Murat; McCoy, Jennifer L. and Luke, Russell E. (2021). “Pernicious Polarization, Autocratization and Opposition Strategies”. Democratization, 28(5): 929-948. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2020.1865316

Stenner, Karen (2005). The Authoritarian Dynamic. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511614712

Storm, Lise (2022). “Political Dynamics in the Arab World and the Future of Ideologies”. Iemed Mediterranean Yearbook 2022 (pp. 78-83). Barcelona: Iemed.

Szmolka, Inmaculada (2013). “¿La quinta ola de democratización?: Cambio político sin cambio de régimen en los países árabes”. Política y Sociedad, 50(3): 893-935. doi: 10.5209/rev_POSO.2013.v50.n3.41350

Szmolka, Inmaculada and Cavatorta, Francesco (2024). “Authoritarian Resilience in MENA Countries in the Era of Autocratization: a Comparative Area Study of Authoritarian Deepening”. Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos, 37: 214-249. doi: 10.15366/reim2024.37.010

Tessler, Mark A. (2002). “Islam and Democracy in the Middle East: The Impact of Religious Orientations on Attitudes toward Democracy in Four Arab Countries”. Comparative Politics, 34(3): 337-354. doi: 10.2307/4146957

Tessler, Mark A. (2007). Do Islamic Orientations Influence Attitudes toward Democracy in the Arab World? Evidence from the World Values Survey in Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Algeria. In: M. Moaddel (ed.). Values and Perceptions of the Islamic and Middle Eastern Publics (pp.105-125). Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/9780230603332

Tessler, Mark A. and Gao, Eleanor (2005). “Gauging Arab Support for Democracy”. Journal of Democracy, 16(3): 83-97. doi: 10.1353/jod.2005.0054

Tessler, Mark A.; Jamal, Amaney and Robbins, Michael (2012). “New Findings on Arabs and Democracy”. Journal of Democracy, 23(4): 89-103. doi: 10.1353/jod.2012.0066

Teti, Andrea; Abbott, Pamela and Cavatorta, Francesco (2019). “Beyond Elections: Perceptions of Democracy in four Arab Countries”. Democratization, 26(4): 645-665. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2019.1566903

Tomini, Luca (2024). Conceptualizing autocratization. In: A. Croissant and L. Tomini (eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Autocratization. London: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003306900

Welzel, Christian (2010). “How Selfish Are Self-Expression Values? A Civicness Test”. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(2): 152-174. doi: 10.1177/0022022109354378

Welzel, Christian (2013). Freedom Rising. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139540919

Welzel, Christian (2021). “Democratic Horizons: What Value Change Reveals about the Future of Democracy”. Democratization, 28(5): 992-1016. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2021.1883001

Welzel, Christian and Kirsch, Helen (2017). “Democracy Misunderstood: Authoritarian Notions of Democracy around the Globe”. World Values Research, 9(1): 1-29. doi: 10.1093/sf/soy114

Weyland, Kurt (2024). “Why Democracy Survives Populism”. Journal of Democracy, 35(1): 43-58. doi:10.1353/jod.2024.a915348

Williamson, Scott (2021). “Elections, Legitimacy, and Compliance in Authoritarian Regimes: Evidence from the Arab World”. Democratization, 28(8): 1483–1504. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1929180

1 The Democratic Culture Index produced by the Economist Intelligence Unit (2006-2023) seeks to identify the extent to which citizens prefer democracy to other forms of government by using 8 items, half of which represent anti-democratic items. Some of them, such as “proportion of the population that believes that democracies are not good at maintaining public order”, are only dubiously appropriate, as they may be misleading and create confusion between autocratic attitudes and critical attitudes towards democracy. The existence of a high proportion of the population that believes that democracy is not the most effective form of government for maintaining public order does not necessarily reflect an autocratic attitude—particularly if those same respondents simultaneously view democracy as a valuable system for achieving other aims they regard as more important than order, such as safeguarding civil liberties or promoting citizen participation in political decision-making.

2 See the 2024 report at https://bti-project.org/en/?&cb=00000

3 See also, among others, the analyses of social protests in the Carnegie Middle East Center’s “Arab Spring 2.0” collection from 2019 to 2022. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/ middle-east/arab-spring-20?lang=en, access July 7, 2025.

4 Not to be confused with other similar concepts that reflect a different reality.

The rise of the “authoritarian notion of democracy” (AND) alludes to the rise of the most extreme anti-liberal understanding of democracy, which results from a misunderstanding of the liberal foundations of democracy and is typically found in societies where culture lacks a solid foundation of emancipatory moral values (Moreno-Álvarez and Welzel, 2014; Wenzel, 2013 and 2021; Welzel and Kirsch, 2017). An AND is operationalised through an index composed of three items contained in the World Values Survey, referring to individuals’ beliefs about the role that religious authorities, the army and people should play in democracy.

On the other hand, the rise of “delegative populism” concerns the rise of social acceptance of government, despite the government’s dismantling of restrictions on its tenure and discretionary authority (Przeworski, 2024).

5 Our model disregards the third dimension that social psychology attributes to authoritarianism, known as “conventionality” or “traditionalism” (Duckitt et al., 2010; Dunwoody and Funke, 2016; Feldman, 2020) because, as Stenner (2005: 85-137) warned, confusing authoritarianism with conservatism is misguided.

6 WVS, V127 (Wave 6) and Q235 (Wave 7).

7 WVS, V128 (Wave 6) and Q236 (Wave 7).

8 WVS, V129 (Wave 6) and Q237 (Wave 7).

9 WVS, V130 (Wave 6) and Q238 (Wave 7).

10 WVS, V62 (Wave 6) and Q154 (Wave 7).

11 WVS, V210 (Wave 6) and Q191 (Wave 7).

12 WVS, V140 (Wave 6) and Q250 (Wave 7).

13 From a theoretical point of view, the model underpinning the indicators does not distinguish between different levels of relative importance. From a data point of view, all indicators were expressed through a single item and the quality of statistical information for all indicators was equally reliable.

14 Although any cut-off point for a continuous index is arbitrary per se, the one chosen here is reasonable according to the geometric aggregation logic of the SAI. An aggregate change of 0.09 requires a previous substantial change in the value of the index indicators, which can be of several types. Among these are: at least a 10 % variation in three indicators, while the fourth remains stable; a 15 % variation in two indicators, with the other two remaining stable; a 30 % variation in one indicator, with the rest remaining stable; and an 8 % variation across all indicators. These alternatives are consistent with our theoretical and operational concepts, which consider processes to have different natures depending on whether one, several or all the properties of the phenomenon are altered. The intensity of these processes varies according to the extent of the change resulting from the aggregation of these variations, once the outcome is mathematically significant.

15 1981-2022, to date.

16 While the value of the electoral process indicator showed a slight improvement, the indicators for rule of law, political pluralism and participation, functioning of government, freedom of belief and expression, rights of association and organisation, and personal autonomy and civil liberties all experienced a marked regression. The last four exhibited the largest declines compared to the rest of the world regions.

17 For political reasons, Wave 6 for Morocco and Wave 7 for Turkey did not include the item “having the army rule” among the questions referring to the assessment of autocratic forms of government for one’s own country. In the case of Egypt, this item did not appear in either wave. In such cases, the value of the indicator “rejection of or little commitment to the democratic rules of the game” was calculated from the arithmetic mean of the percentage of “good” or “very good” responses for the other authoritarian items, and “bad” or “very bad” responses for the democratic item.

It should be noted that it was not possible to use data imputation for missing values either through time series analysis or through a proxy item. The reason for this is that we did not have the necessary time series, nor do WVS questionnaires contain questions that could be operationalised as a proxy for this item.

18 See the collection of annual Global Peace Index reports published by the Institute of Economics and Peace in the study period observed at Global Peace Index - Institute for Economics & Peace.