Normalizing Protest Events.

The Case of Spain’s 8M Protest (2018-2019)

Eventos normalizadores de la protesta.

El caso del 8M en España (2018-2019)

Manuel Jiménez-Sánchez and Javier Águila Díaz

|

Key words

Normalization of Protest

- Political Participation

- 8M

- Feminist Movement

- 15M

- Political Culture

|

Abstract

The generalization of protest implies a process of normalization in the profiles of those participating in low-cost, extra-institutional political activities such as demonstrations. This study suggests that certain politically significant protest events act as “normalizing moments” since they attract participants having socio-demographic and attitudinal characteristics that are less than typical with respect to these types of political expression. Relying on survey data, the 8M mobilizations of 2018 and 2019 serve as an illustrative case to assess the normalizing impact of this type of events. First, participants in the 8M protest are compared with those of other mobilizations from the same period, and those of the 15M protests that took place years earlier. Second, the entry and exit flows of the 8M participants are examined.

|

|

Palabras clave

Normalización de la protesta

- Participación política

- 8M

- Movimiento feminista

- 15M

- Cultura política

|

Resumen

La generalización de la protesta implica un proceso de normalización en los perfiles de quienes participan en actividades políticas extrainstitucionales de bajo coste, como las manifestaciones. Este trabajo plantea que ciertos eventos de protesta políticamente significativos actúan como «momentos normalizadores», al atraer a participantes con características sociodemográficos y actitudinales menos habituales en estas formas de expresión política. A partir de datos de encuesta, se analizan las movilizaciones del 8M de 2018 y 2019 como un caso ilustrativo para evaluar el impacto normalizador de este tipo de eventos. Para ello, en primer lugar, se comparan participantes en el 8M con asistentes a otras movilizaciones del mismo periodo y a las protestas del 15M unos años antes y, en segundo lugar, se examinan los flujos de entrada y salida de participantes en el 8M.

|

Citation

Jiménez-Sánchez, Manuel; Águila Díaz, Javier (2025). “Normalizing Protest Events. The Case of Spain’s 8M Protest (2018-2019)”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 190: 147-172. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.190.147-172)

Manuel Jiménez-Sánchez: Universidad Pablo de Olavide | mjimsan@upo.es

Javier Águila Díaz: Universidad Pablo de Olavide | jagudia@upo.es

Introduction

Barnes and Kaase (1979) suggested that the increase in protest participation would extend beyond the conflict-ridden 1960s. Their prediction about the routinization of protest activity was so accurate that the label “unconventional” that they proposed to refer to these activities has become obsolete. Years later, Kaase (2007) stated that protest had become a normal non-institutionalized form of political involvement.

Various studies have addressed the extent of protest, examining the profile of the protesters, their demands and the implications for representative democracy. The initial works associated protest with a specific “critical” citizen sector which was characterized by having a high education level, being attentive to politics and having a progressive bias (Dalton, 2008; Klingemann, 2015; Norris, 2011). To the extent that their demands, with a post-materialist bias (Opp, 1990), do not coincide with those of other non-participating social sectors, the spread of protests began to be seen as a new source of political inequality in representative democracies (Verba, 2003). In fact, Barnes and Kaase (1979) already detected major participatory inequalities according to sociodemographic variables: men, young people and those with more education displayed a greater propensity to protest.

Empirical research points to a normalization process driven by the incorporation of broader and more diverse social sectors into extra-institutional activity, thus reducing the participatory inequality between participants and non-participants (Aelst and Walgrave, 2001). Although the evidence typically refer to the diversification of voices in protest rather than the content of their demands, the analysis is relevant in order to better understand the patterns of political inequality in representative democracies. Collectively, these studies partially support the hypothesis of the normalization of the protest participant’s profile, especially in non-violent forms such as demonstrations. On the one hand, a balanced presence is consolidated in terms of gender, and, to a lesser extent, age; on the other hand, inequality in terms of educational attainment persists, with the least educated continuing to be underrepresented. Using data from the ESS of 2004, Gallego (2007) highlighted the over-representation of the youngest and most educated in protests, finding no significant differences in income, ethnic minority or socioeconomic status. Comparing participation forms in distinct countries of the ISPP 2004, Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier (2010) pointed out that forms of extra-institutional participation tend to be more inclusive in terms of age or gender, but less so in terms of educational level.

Normalization in attitudinal aspects is less clear. Interest in politics and dissatisfaction with the functioning of democracy continue to be elements that differentiate protest participants from citizens in general (Grasso and Giugni, 2019). Likewise, the progressive bias detected in the initial studies persists, with a predominance of left-wing sectors (Borbáth and Gessler, 2020; Kostelka and Rovny, 2019; Saunders and Shlomo, 2021; Torcal, Rodon and Hierro, 2016).

This empirical literature demonstrates that the normalization of the protest participants profile depends on the specific context and does not take place in a uniform and linear process. Although it is closely linked to the generalization of protest, it is not fully determined by the occurrence of protests. Contextual factors, such as the extent of critical citizenship, the characteristics of the political system or the strategies of the authorities, may modulate this general tendency. Given the relevance of these structural factors, this study argues that the normalization of participants takes place in impulses, depending on the occurrence of mobilization events or cycles that are especially significant or “transforming” (Berezin, 2017). These are the events that bring unusual profiles out onto the streets, providing political learning experiences that encourage subsequent participation (Giugni and Grasso, 2016; Jiménez-Sánchez and García-Espín, 2023).

Spain can be considered an illustrative example of the extension of peaceful forms of protest. Polls have situated it amongst the first (if not the first) of all European countries having the highest percentages of demonstrators (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2024). It also reveals an advanced case of protester profile normalization. Providing data on protest participants, Jiménez-Sánchez (2024) found that from the 1980s to prior to the mobilization cycle spurred by the economic crisis, there was a trend of normalization in terms of gender, age and (to a lesser extent) habitat, educational level and ideology. However, in the Spanish case, the incorporation of conservative sectors to protest activity, while still underrepresented, is a notable feature, as well as the presence of older adults and the growing role of women (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2011, 2014).

The extension of the protest in Spain may be attributed, among other factors, to the combined effect of a political system that is not highly sensitive to citizen demands through institutionalized channels (Fishman, 2011) and a political culture that has incorporated the repertoire of peaceful protest. The occurrence of mass mobilizations attracting very heterogeneous participants, such as those against ETA terrorism in the nineties, those against the Iraq war or those protesting the 11M attacks in Madrid, have played a fundamental role in the creation of this element of political culture. These events were politically significant and are considered collective learning experiences that have favored the incorporation of peaceful protest into sectors without previous experience (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2011). More recently, the 15M movement and the anti-austerity and pro-democracy protests during the Great Recession have reinforced the perception of street protest as a legitimate tool for citizen participation (Jiménez-Sánchez and García-Espín, 2023). Thus, the combination of a democratic political system that requires conflict in the streets to hear citizens’ demands and the occurrence of massive and significant protest events has shaped a protest culture that is prone to extra-institutional participation.

In this work, we address the idea that the occurrence of politically significant protest events acts as normalizing moments that broaden participation to sectors having less experience and that tend to be further removed from the dominant critical (and progressive) citizen profile. As a case study, we use the mass mobilizations of International Women’s Day in Spain during 2018 and 2019, which gave rise to the “8M movement”. The starting hypothesis is that these mobilizations have also served as politically significant events that reflect and simultaneously contribute to the protest normalization process.

To investigate this question, data from a survey conducted in 2019 was used. First, the sociopolitical profile of the 8M participants was compared with that of other protests during that period as well as with the profiles of those who participated in the 15M years before. Then, the profiles of different groups were compared, based on their 8M experience, paying special attention to individuals who joined these mobilizations for the first time.

8M as a transformative, reflection and stimulus event of protest normalization

Since the United Nations declared March 8th as International Women’s Day in 1975, this event has been celebrated worldwide in diverse manners and with distinct participation levels (see www.internationalwomensday.com). Feminist movements have taken advantage of this institutional commemoration to raise awareness of persistent gender inequalities. However, by the end of the last decade, celebrations had become more popular and contentious, including calls for women’s strikes and massive attendance at marches (Watkins, 2018). Noteworthy examples of this include the Women’s March in the US taking place in 2017, protests against the prohibition of abortion in Poland in 2020, and viral campaigns such as #MeToo initiated in the US, #NiUnaMenos in Argentina, #IWillGoOut in India and most recently, #SeAcabó, against machismo in sports.

In Spain, International Women’s Day became especially significant in 2018 and 2019, giving rise to the “8M movement”. Following the 15M (the “Indignados” movement) and the anti-austerity campaigns that followed it, the feminist movement experienced an organizational transformation and renewed energy (Galdón, 2020). In 2012, the Marea Violeta (Violet Tide) arose to oppose the restrictive labor reforms and setbacks in equality policies. The feminist response intensified in successful mobilizations against the proposed 2014 reform of the abortion law and social media protests, such as the #YoSiTeCreo movement against gender violence and sexism, driven by the judicial sentence issued in the 2018 “La Manada (wolf pack) rape case”.

At the same time, the 8M is part of a period of intense mobilization in Spain, where protests by young people against climate change or the mobilization of pensioners are also especially noteworthy. Using official data on the celebration of protests, Jiménez-Sánchez (2024) referred to 2018, as well as 2012 and 2013, as one of the highest peaks in the historical series. Polls on participation in protests also characterize this as a period of broad participation, although it did not reach the participation rates recorded during the Great Recession or in the demonstrations against the Iraq war in 2003 (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2024: 73).

These mobilizations can be considered expressions of the legacy of the 15M in the Spanish protest culture. One feature shared with the 15M is that these protests appeared to be spontaneous and non-partisan citizen initiatives (Flesher, 2020; Jiménez-Sánchez and García-Espín, 2023; Jiménez-Sánchez, Fraile and Lobera, 2021). Together with their configuration as hybrid media events, these elements may explain their high public visibility and receptivity, as well as the expansion of their social support beyond regular activists and protesters, resulting in transversal and intergenerational movements.

Therefore, during the 2018-2019 period, the March 8th mobilizations became a citizen movement with great normalizing potential. In 2018, approximately 21 % of all people over the age of 18 participated in the strike or in any of the 120 demonstrations and rallies held (Campillo, 2019). In 2019, the event grew with some 500 demonstrations and countless protest activities, having a similar or even higher participation: according to the data used in this work, 22 % of the surveyed individuals participated in these acts.

The media highlighted the massive and historic nature of the mobilizations, emphasizing their intergenerational nature, their extension to rural areas and their politically transversal nature. Thus, the 8M mobilizations of 2018 and 2019 offer an ideal informative case study to explore the normalizing impact of these events. By comparing the sociodemographic profile of the participants from the 15M mobilizations with those of other 2018-2019 mobilizations, it is possible to measure this normalizing impact. This comparison with the 15M mobilization is especially relevant given its transformative nature and its description as a massive and transversal movement (Della Porta et al., 2018).

Expressions of the normalization of the profile of the participant in the protest. Initial hypothesis

The main objective of this work is to analyze the 8M mobilizations as politically significant events that reflect and contribute to the process of participant normalization in demonstrations. Specifically, it aims to verify the normalizing impact of this event on different characteristics associated with participatory inequality. The initial or guiding hypotheses are based on the aforementioned empirical literature and the results of previous studies on the normalization of participation in demonstrations in Spain (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2011, 2024).

Is there full participatory gender equality? The incorporation of women in the protest movement is perhaps the most apparent factor in the normalization process (Gallego, 2007; Jiménez-Sánchez, 2011; Marien, Hooghe and Quintelier, 2010). Past studies in Spain have demonstrated the equal presence of men and women and even a trend for female overrepresentation (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2024). Obviously, in the context of the 8M, it is expected that women will be overrepresented. However, the aim is to measure this presence, especially in those who are participating for the first time. The response is compared with the data on participants from other mobilizations and in those of the 15M.

Is this a movement of intergenerational confluence? Another factor encouraging normalization is the balanced presence of distinct age groups. Studies have revealed a substantial reduction in the overrepresentation of young people (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2024). The 8M movement has been presented by the media as an intergenerational movement and one that incorporated a new generation of feminists (Bellido, 2019). The initial hypothesis predicts a similar presence of the different generations amongst the regular participants and an overrepresentation of young people amongst the newcomers. In the case of the 15M, this observation allows us to contrast the contribution of both events in the incorporation of young people, whereas the data from other mobilizations allows us to contrast the hypothesis of participatory equality in terms of age.

Does this movement reach rural areas? The transformation of protest in the digital society has accelerated the process of incorporating residents in small municipalities (Sánchez, 2018). As an initial hypothesis, it is anticipated that the 8M movement has expanded to rural areas, which would translate into a reduction in the influence of the geographic environment in participatory inequality. Again, the contrast with participants in the 15M or in other demonstrations of the same period allows us to measure this dimension of normalization.

A connective action movement? The normalization of protest is related to the process of cognitive mobilization in post-industrial and digital societies (Dalton, 2000). The expansion of education and access to information through the Internet increases the cognitive and informational resources necessary for participation (Verba, Schlozman and Brady, 1995). Digital social networks have increased the potential for contacts and access to information, playing a central role in shaping mass mobilizations such as the 8M and the 15M (Jiménez-Sánchez, Fraile and Lobera, 2022). Therefore, it is expected that there will be a connection between education level and social media use and participation in protests, especially between newcomers in the 8M. However, in line with past studies on the normalization in Spain, it is expected that this connection will be weaker with regard to education.

Is it a mainstream movement? In the seminal studies on the profile of the participant in protests, the figure of the critical citizen is highlighted, characterized by educational level, interest in politics, progressive bias and discontent with the functioning of democracy (Barnes and Kaase, 1979). Prior empirical studies have suggested the persistence of these biases (Borbáth and Gessler, 2020; Kostelka and Rovny, 2019; Saunders and Shlomo, 2021; Torcal, Rodon and Hierro 2016). However, in Spain, the growing inclusion of moderate and conservative sectors in the protest movement has been observed (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2011, 2024), influenced by experiences of the mobilizations against terrorism at the end of the last century and, later, the movements of confrontation with the progressive governments, such as during the first legislature of the Zapatero government (Aguilar, 2010). In line with these results and the media characterization of the 8M as a transversal movement (Romero, 2019), the starting hypothesis focuses on the possibility of attenuating these traditional attitudinal biases. The contrast with participants in other demonstrations and in the 15M allows us to dimension this impact towards a mainstream profile.

A feminist movement? With respect to the previous hypothesis, it is also relevant to consider the degree of participant identification with the social movements that promote these events and how much they fight to create their meaning, in terms of both participants and society in general (Melucci, 1995). In this sense, the extent to which the 8M incorporates individuals that are less identified with the feminist movement is examined, considering that the mobilization process itself may activate identification processes.

A legacy of the 15M? As seen, the 8M has clear connections with the 15M movement. It has been referred in some media as the “women’s 15M” (Avendaño, 2018). Protests during the Great Recession led to the inclusion of broad social sectors into the movement. The effects of these mobilizations have transcended those who are directly involved, leaving their mobilizing mark on the political culture of large sectors of the population (Jiménez-Sánchez and García-Espín, 2023). In this sense, it is expected that participants, including newcomers, will be differentiated by having a greater degree of sympathy towards the 15M.

Methodology

To explore these questions, we analyzed data from a 2019 web-based telephone survey having a sample of 2159 cases representative of the Spanish population over the age of eighteen. The survey collected data on participation in distinct protest events: participation in the 8M demonstrations in 2019, 2018 and previous years, participation in other demonstrations during the past twelve months and prior participation in protests related to the 15M. This data was used to create the four dependent variables used in this work.

First, the participant profiles were compared (versus non-participants) in three types of events: the 8M demonstrations in 2018 and 2019, other protests during this period and mobilizations related to the 15M. Approximately 30 % of the surveyed individuals participated in at least one of the two large feminist mobilizations taking place during these years, whereas 26 % participated in another mobilization taking place during the period between both mobilizations. Finally, 13.5 % recalled having participated in the 15M demonstrations. The comparison with participants in other demonstrations in 2018-2019, including a greater diversity of topics, offers a broader picture of the normalized nature of the participant profile at this time. The comparison with the 15M participants offers a contrast with another (potentially) normalizing event.

Secondly, a fourth dependent variable that classifies respondents into four groups based on their experience in the 8M is also explored. The “regular” group identifies individuals who participated during the 2018-2019 cycle and who had already participated on previous occasions. It makes up 16 % of the sample, a bit over half of the participants, and it is likely to include activists and sectors that are more closely identified with the feminist movement. The “newcomers”, individuals for whom participation in 2018 or 2019 marked their first experience in this protest day, represent 14 % of the sample, and their profile provides insights into the characteristics of those joining the protests during this period. In contrast, the group of former participants offers information about the characteristics of people who, having participated in the past, did not return on this occasion. It is reasonable to believe that either because their previous participation was anecdotal or because they have experienced attitudinal or biographical changes, this led them to cease participating. This group makes up approximately 5 % of the sample. Finally, the individuals that declared themselves to have never participated in the 8M protests make up 64 % of the sample. In this case, it is expected to find an attitudinal profile that is distanced from the feminism or political profile, in general.

The comparison of participants in the three mentioned types of events and the comparison of the groups of participants has allowed us to consider the 8M in a broader temporal process of protest normalization and to assess its contribution to this process. The analysis has a descriptive orientation and is based on the development of representation indices and logistic regressions for a series of sociodemographic (gender, cohort, size of municipality of residence, education level, social media use) and attitudinal (ideology, interest in politics and satisfaction with the government) variables that are commonly used in qualitative studies on participation. The comparison of profiles of participants in the 8M also includes attitudes (sympathy) towards the feminist movement and towards the 15M as additional indicators of politicization.

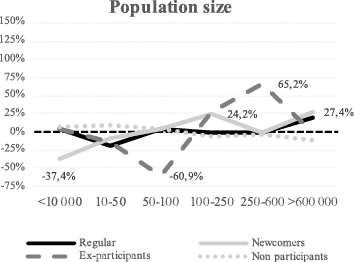

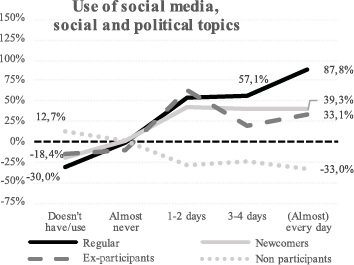

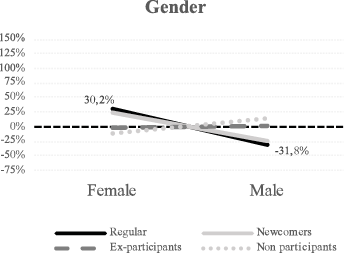

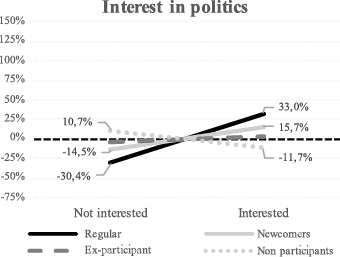

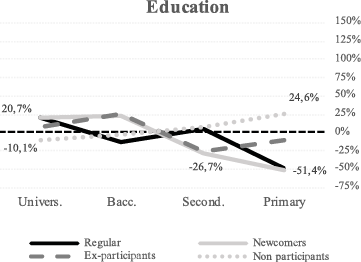

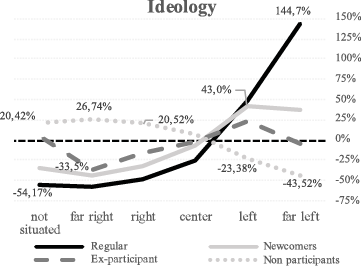

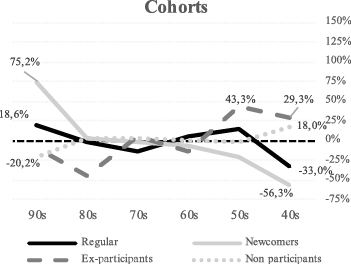

The representativeness of participation in the 8M within the context of protest normalization

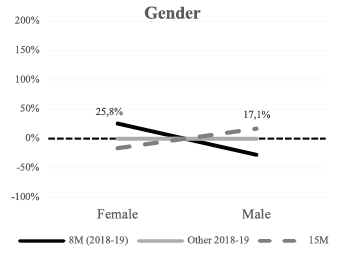

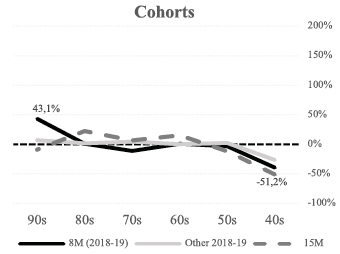

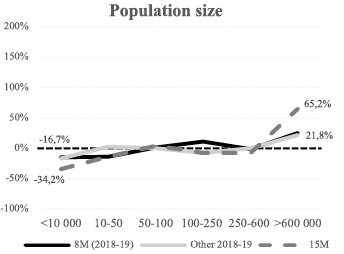

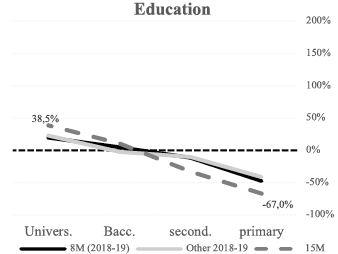

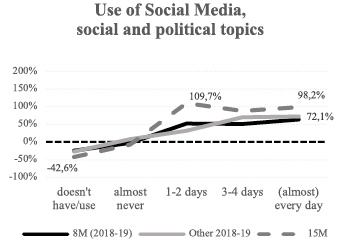

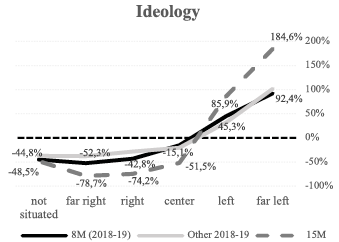

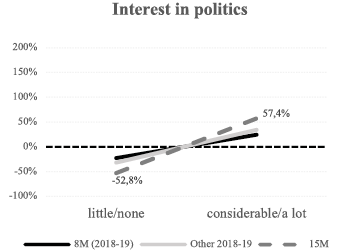

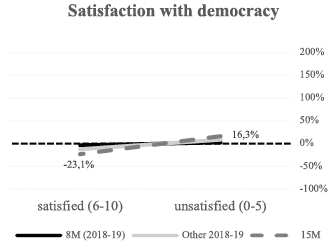

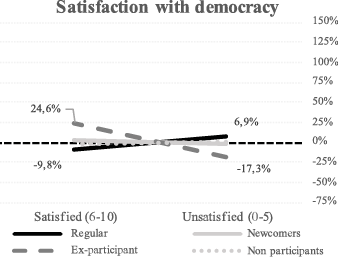

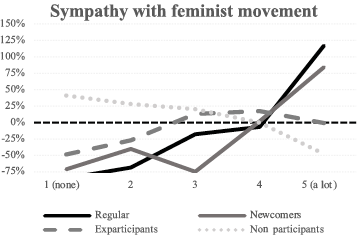

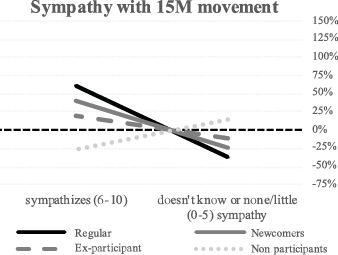

The following series of figures presents the values of the Representation Indexes (RI) in percentage terms for the different categories of the sociodemographic and political attitude variables considered. Values close to zero (dashed horizontal line) indicate a proportional presence to the weight of this category in the general population (over 18 years of age), whereas values above or below zero indicate over or under-representation of said category amongst the protesters. Therefore, a value of -50 % indicates that, amongst the participants, we find half of the individuals in this category, as compared to the general population, and a value of 100 % indicates double the presence. The range of values on the vertical axes remains constant, from -100 % to 200 %, to facilitate visual comparison of the results of the eight variables represented. Each figure presents the IR for the three types of events considered: the 8M demonstrations during the 2018 and 2019 cycle (black line), other demonstrations during that period (light grey) and those linked to the 15M (dark grey dashed line).

The tendency of the lines to overlap indicates a pattern of participatory inequality that is common to the three events. However, the greater proximity of the grey lines (participation in other demonstrations) to the horizontal axis suggests a more normalized profile in this case. The greater heterogeneity of this group is expected, given the diversity of demands that potentially underlie this participation. Likewise, the comparison of the other two lines with respect to the horizontal axis indicates that the 8M (black line) led to a more heterogeneous profile on the streets than the 15M (dashed line).

One exception here is gender. As expected, women are overrepresented (26 %) in the 8M demonstrations. In all, 35 % of the protesters were men. On the other hand, in the 15M, men made up 57 % of the participants (implying 16 % underrepresentation of women). In the participation in other demonstrations in 2018-2019, there was an equal presence of men and women, confirming the trend of normalization in terms of gender that was detected since the onset of the century in Spain (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2011).

The 8M and the 15M share the overrepresentation of young people. This feature is especially relevant in the case of the 8M, although both events may be considered to be critical moments of initiation (socialization) in protest for new generations. On the other hand, the data, specifically that referring to other demonstrations, indicates that the protest remains in people’s political repertoire throughout their lives and only in older cohorts does it represent an obstacle to participation.

The results also indicate the extension of the protest to residents from all types of municipalities, although those in large cities tend to be overrepresented. By type of events, this inequality was more pronounced in the mobilizations of the 15M. The 8M maintains this urban character, although less accentuated, confirming a greater extension to the rural area. In the 15M, inhabitants of cities with six hundred thousand or more inhabitants are overrepresented by 65 %, in the 8M this disproportion moderates to 22 %.

The results point to the persistence of cognitive resources, interest in politics and, very markedly, ideology as factors of participatory inequality. There is an under-representation of sectors without studies or with primary studies, which in the case of the 15M reached 67 %. However, the group of people without studies represents approximately 10 % of the population over eighteen years of age, so its overall effect in terms of participatory inequality has a limited scope. The inequality is more evident with regard to the use of social media (related to issues of social or political interest). There was a clear division between sectors who do not have or barely use them for that purpose (60 % of the sample) and those using them regularly (at least one or two days a week). In the case of participation in the 8M and in other demonstrations in 2018 and 2019, the overrepresentation is close to 70 % and reaches up to 100 % among those who participated in the 15M. That is, for the 15M, twice as many participants use social media than in the general population, emphasizing the role of social media as a defining element for participation in that event.

Regarding attitudes, people interested in politics are overrepresented in all three types of events, but especially among the 15M participants. The overrepresentation reaches 57 % as compared to 25 % in recent mobilizations. The same occurs in the case of ideology, where there is a clear left-wing bias, especially accentuated in the case of the 15M, where we find three times more people on the extreme left than in the general population and twice as many in left-wing positions. However, in the protests of 2018-2019, including the 8M, this ideological bias is attenuated, and the presence of participants with moderate ideological positions approaches a representation that is almost proportional to their weight in the population. The differences are smaller if we consider satisfaction with democracy, and only in the case of the 15M movement do we find slightly more dissatisfied people than in the general population (16 %). However, the time reference for this assessment is the time of the survey, several years after the 15M movement.

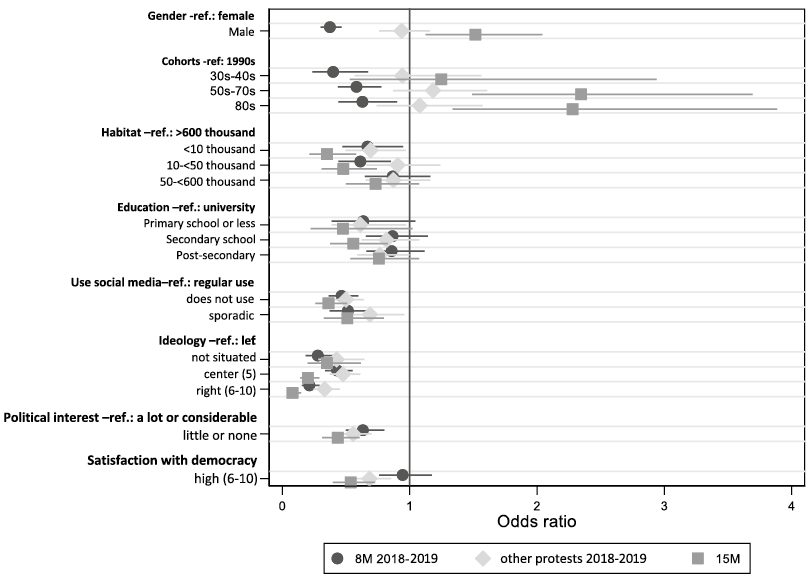

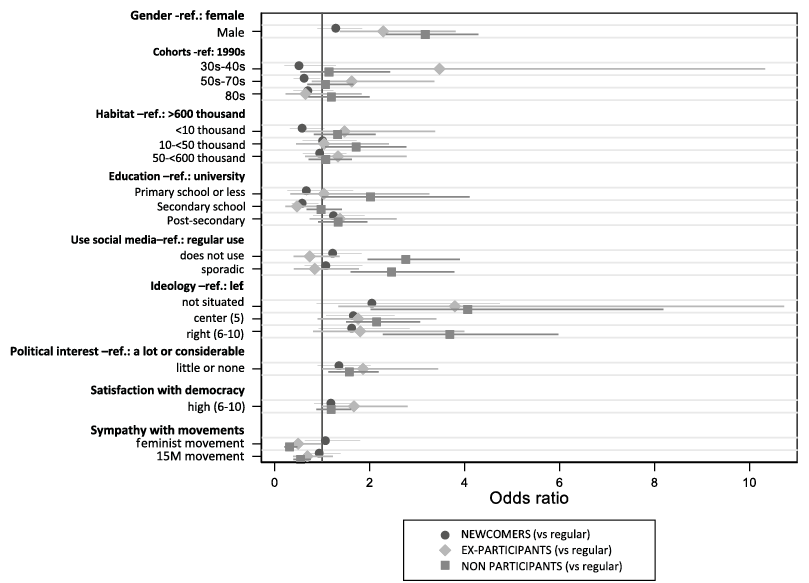

Multivariate analysis allows for the measurement of the weight of these variables in shaping the participant profiles. Figure 2 summarizes the results, expressed as odds ratio, of the logistic regression models for the three events: the 8M (circular markers), other demonstrations (diamond) and the 15M (square). These values are interpreted as indicators of the effect of each variable on the probability of having participated (versus not having participated), maintaining the other variables constant. When the values fall to the right of the vertical line of the graph (greater than 1), there is a positive effect of that variable. When they fall to the left, this effect is negative. And when the confidence intervals include the value 1, the effect is not considered to be statistically significant. The further the values are from the line, the greater the weight of that variable in the probability of participating. All of the variables are analyzed as categorical, generally using as a reference the category with the greatest overrepresentation in the 8M mobilizations, such that the odds ratio tend to be less than 1.

The results confirm the pattern drawn by the gender representation indices: a greater probability of participation of women in the 8M, of men in the 15M and their irrelevance (in statistical terms) for participation in other demonstrations during 2018-2019. Specifically, the probability of having participated in the 8M is 2.7 times less between men as compared to with women, while in the 15M, this probability is 1.5 times greater.

The 8M is also characterized by the overrepresentation of younger people: those born in the 1980s are 1.6 times less likely to participate than those born in the 1990s. However, these differences are not seen either in the demonstrations held during 2018-2019 or among participants in the 15M, where both the younger cohorts (those from the 1980s in the case of the 15M) and the older ones were mobilized. This result qualifies the bivariate analysis, regarding the overrepresentation of young people in the 15M. Although there was a clear protagonism of young people at that time, they were largely accompanied by groups of adults.

Habitat remains a factor associated with participation in the three types of events, reducing (with varying intensity) the probability of participation of residents in small municipalities. Thus, when compared to residents of large cities, the probability of participating in the 15M was 2.8 and 2.1 times lower for residents of municipalities with less than ten thousand and between ten thousand and fifty thousand inhabitants, respectively. This negative effect is less pronounced (0.5) in the context of the 8M, and it only significantly affects residents in the smallest municipalities in terms of their participation in other demonstrations (with a probability that is 1.4 times lower). Therefore, although territorial inequality persists, in the 8M it becomes less intense, in line with a possible general trend of the protest spreading to rural areas (which is best seen when observing attendance at other demonstrations in 2018-2019).

One nuance evidenced with regard to the previous bivariate analysis is that education level does not significantly affect the probability of participating in 8M, unlike the other events considered. This would, therefore, be a normalizing effect of 8M that was not clearly seen in the representation indices. On the other hand, the use of social media is maintained as a determinant of participation in all three events. People who do not use social media or do so sporadically are twice as likely to participate in 8M as regular users. In the case of the 15M, the probability of participation of non-users (as compared to regular users) was reduced by three times.

However, the factor with the greatest influence on the likelihood of participating in all three types of events is ideology. Being ideologically on the right, in the middle, or not being on the scale significantly reduces the likelihood of participating, as compared to those who are on the left. The differences are especially significant in the case of 15M. Thus, while in the 8M, the probability of participating was twice as low in centrist positions and 4.7 times lower for right-wing positions, these odds increased to 5 and 12.5 respectively in the 15M model. In this sense, it is confirmed that the usual progressive bias of the protest is somewhat more moderate in the case of the 8M, in a (weak) trend towards a certain ideological normalization of participation in demonstrations appears a bit more in the case of the other 2018-2019 demonstrations.

The trend towards a mainstream profile in the demonstrations is seen in the interest in politics and in the satisfaction with democracy. While the probability of participating in the 15M decreases 2.3 times among those with little interest in politics, in the case of the 8M it is 1.6 times (odds of 1.7 for other demonstrations). In the 8M, the degree of satisfaction with democracy does not reflect significant differences in the probability of participating, while in the rest of the demonstrations, and in the 15M, it reduced the probability of participating by 1.5 and 1.9 times respectively. Although moderate, this approach to a more mainstream citizenship profile would be a normalizing effect of 8M.

Looking at participants in other demonstrations in 2018-2019, the results indicate a normalized profile in terms of gender and, relatively, in terms of age and habitat. The results indicate that factors such as educational level, social media use, ideology or political interest continue to distinguish the protesters, biasing their representativeness. Considering participation in the 8M, the results indicate that this event also contributed to the incorporation of the youngest (not only women) into the protest activity. Compared to the 15M, it turned out to be somewhat less urban and more capable of mobilizing people having a lower level of education, more ideologically moderate and less interested in politics. Its normalizing impact lies precisely in its ability to mobilize a more mainstream profile.

Participant types. Inflows (and outflows) in the 8M

Comparing the different groups of people according to their experience of participating in the 8M (regulars, newcomers, former participants and non-participants) helps to scale and characterize the normalizing impact of the 8M. Sixteen percent of the individuals in the sample are regular attendees of the 8M (they had participated in the event prior to 2018). During this cycle, 14 % (almost half) of the participants joined the mobilizations for the first time. This influx of participants contrasts with a lower number of departures: 5 % of ex-participants. These data confirm the massive nature of the mobilizations (possibly the largest in democracy) and their ability to expand their support bases.

Figure 3 represents the values of the representation indices (see previous explanation for Figure 1) for the four categories: regular participants, newcomers, former participants, non-participants.

In general, two patterns of analytical relevance are noteworthy. Firstly, considering the distance of the lines from the central axis, it is seen that the variables age, social media use, ideology and sympathy for the feminist movement tend to be distanced from the central axis to a greater extent, indicating their importance in differentiating between the groups.

Secondly, notable differences are evident in the trajectories of the lines: non-participants tend to display different trends compared to the other three categories, especially with respect to regulars and newcomers. The most differentiated group is that of non-participants, especially in terms of social media use and attitudes such as sympathy towards the feminist movement or the 15M, ideology and interest in politics. On the other hand, the most visible difference between regulars and newcomers relates to age. In terms of attitude, newcomers tend to follow the norm to a greater extent than regulars, while former participants are situated in a more intermediate position. Former participants, however, stand out, with a greater relative presence of people who are satisfied with democracy.

Considering specific variables, the overrepresentation of women in the 8M cycle is confirmed, finding a lower percentage among newcomers (23 %) compared to regulars (30 %). No significant differences are seen in the group of former participants. That is, considering the inflow and outflow, the net balance contributes to the feminization of the protest.

Regarding age, the younger generations participate more and on a regular basis. However, the differences between regular and non-participants are small in the intermediate age groups. These results suggest, on the one hand, the general trend of profile normalization (with a lack of significant differences in the intermediate ages) and on the other hand, the capacity of the feminist mobilization cycle to attract young people, born in the nineties. The overrepresentation of ex-participants (and non-participants) amongst the older cohorts may be due to their lower biographical availability (McAdam, 1986) and to the greater relative weight of the politically less active sectors and those related to the movement.

The values for habitat indicate more clearly the tendency towards normalization: the lines tend to overlap near the horizontal axis. The most notable difference occurs in the newcomers, with an underrepresentation of residents in small municipalities and a moderate overrepresentation of residents in large and intermediate municipalities. Similarly, the differences regarding education level are also moderate. Individuals with higher levels are slightly overrepresented in the group of regular and newcomers, whereas those with primary education are underrepresented (-50 %). On the other hand, social network use stands out as a differentiating factor in the participant profile. Overrepresentation is especially high amongst the regular participants (88 %).

As for the attitudinal variables, ideology stands out as a factor that differentiates the four groups, especially between regular and non-participants. A clear division exists between the underrepresentation of those who are situated more to the right compared to the overrepresentation of those on the left, especially in regular participants (-58 % and 145 %, respectively). This overrepresentation is somewhat moderated amongst newcomers and, especially, former participants. Individuals situated in the center with regard to ideology are represented proportionally in the four groups, indicating the ability of the feminist protest to broaden the ideological spectrum of its supporters.

To a lesser extent, interest in politics also differentiates the four groups, with an overrepresentation of interested individuals amongst the regular participants (33 %) and newcomers (16 %). Satisfaction with democracy only affects the representation of former participants, in which a moderate overrepresentation of people satisfied with democracy (25 %) is found. As for sympathy for social movements, as expected, regulars and newcomers attract both sympathizers of the 8M and those with a favorable past experience in the 15M.

Who joins, who leaves and who stays on the sidelines

of the 8M?

To analyze the partial effects of the different variables on the differentiation of the four groups, a logistic regression analysis was performed. Figure 4 reveals the results of the comparisons of newcomers, (circular marker), former participants (diamond) and non-participants (square) with the group of regular participants. The values represented by these markers (odds ratio) can be interpreted as indicators of the weight of the different variables in the probability of belonging to that group instead of belonging to the regular participant group, keeping the values of the other variables constant.

Who stays on the sidelines of the 8M? Comparing non-participants with regular participants confirms that being male or living in a small municipality increases the probability of non-participation 3.2 and 1.7 times, respectively. However, the differences in terms of cohorts and education level disappear in the multivariate analysis, highlighting the normalizing influence of the 8M with regard to these sociodemographic traits.

The most determinant variables for not participating in these mobilizations are social media use and some of the political attitudes considered. Not using social media or using it only sporadically, compared to using it regularly, increases the possibility of not participating by around 2.5 times. Likewise, the probability of not participating is 3.7, 2.9 and 1.8 times higher amongst those who do not situate themselves ideologically, or who are situated to the right or the center, respectively, compared to those situated on the left. Not being interested in politics makes an individual 1.5 times more likely to join the group of non-participants. Likewise, being sympathetic towards the feminist movement or the 15M movement reduces the possibility of being a non-participant 3.2 and 1.8 times respectively, compared to those sympathizing with these movements. Satisfaction with democracy is the only attitude that does not influence the probability of belonging to one group or the other.

Who participates in the 8M? In sociodemographic terms, the differences between regular and newcomers appear in age: compared to the 1990s cohort, the probability of joining the 8M is 1.6 times lower for the older adult cohort (1950-1979). On the other hand, no significant differences are found with regard to the size of the place of residence, education level or social media use. Furthermore, gender differences are not evident: women remain overrepresented in the inflows. Both groups are similar in terms of attitudes. For example, they share (high) levels of sympathy for the feminist movement and for the 15M. The only exception is the greater probability of newcomers to be situated in centrist positions (compared to not being placed on the scale). In this sense, newcomers contribute to normalizing the protester profile, incorporating the youngest and somewhat more moderate profiles (mitigating the left-wing ideological bias and the overrepresentation of young adults). Furthermore, by resembling the regular group, they accentuate the underrepresentation of residents of small municipalities and individuals with a lower education level. This suggests that the overrepresentation observed in the bivariate analysis is mainly due to the inflow.

In short, newcomers push the protester profile towards the overrepresentation of the most educated and residents of large cities; but, at the same time, they serve to somewhat moderate the gender imbalance, and, with their youth, they contribute to the balanced presence of the cohorts. However, the most notable normalizing effect is that of ideological moderation.

Who leaves the 8M? Former participants are the smallest group (approximately 5 %). They may be considered the least faithful individuals who, for various reasons, have not continued to participate in the 8M during the last cycle. The comparison with regular participants suggests that they are mainly male, belonging to older cohorts and have a lower educational level. It is 2.3 times more likely that a male will be an ex-participant than a female. Similarly, the probability of being an ex-participant is 3.5 times higher among octogenarians, compared to younger people. Among those who do not situate themselves on the ideological scale or who have little interest in politics or express greater satisfaction with the functioning of democracy, the probability of leaving (versus continuing) increases significantly, up to 1.9 times, for example, in the case of little political interest. These results indicate that the exit reduces the presence of older cohorts and less politicized profiles. Sympathy towards the feminist movement also helps in the understanding of this exit and it suggests the importance of identity ties with social movements to understand the continuity of the mobilization. In this sense, former participants are similar in terms of attitudes to the non-participants, suggesting that protest normalization varies depending on the intensity of participation.

Conclusions

Returning to the initial questions or hypotheses, the results indicate, firstly, that although the 8M protests are led mainly by women, they should not be considered exclusively female. A certain greater presence of men amongst newcomers (although still underrepresented) and among the former participants suggests a significant presence of men, possibly occupying a second line of sympathizers in these protests or participating in a less regular manner. Regarding its impact on normalization, the 8M appears to have contributed decisively to the reversal of the traditional overrepresentation of men on the street that has been suggested in the literature. The gender balance is observed when considering participation in other demonstrations of the same period, as previously detected in some works (Jiménez-Sánchez, 2024). On the other hand, the data also indicate that this did not occur during the 15M protests, which displayed an overrepresentation of men.

Secondly, the results confirm the intergenerational convergence, reflecting a broader trend of age-based normalization of this type of protest. This trend is also evident in the data on 15M. In this sense, both events may be considered critical moments of initiation (socialization) into protests for the new generations.

Thirdly, the data suggest that the 8M protests maintain an urban bias that is less pronounced than that of the 15M, in which there was less participation by residents in small municipalities. The image offered by the analysis of participation in other events confirms this extension of the protest to rural areas, except in the smallest municipalities.

Fourthly, the results reveal a process of normalization in educational level. Participation by individuals having a lower level of education is a normalizing effect of the 8M. On the contrary, the relevance of the use of social networks is an explanatory factor for participation. Social networks were decisive in the 15M and continue to be so in subsequent mobilizations (Castells, 2015; Flesher, 2020). In the context of a general increase in the population’s education level and an extension in connectivity of the mobilization processes, the use of social media may be considered a relevant factor in the participation in the 8M and, in general, in the extra-institutional forms of participation.

Fifthly, the transversality of the 8M has also been evaluated, along with its ability to attract ideologically moderate profiles or those who are less critical or attentive to politics. Despite the generally progressive and politicized tendency of those participating in protests, the results suggest the extension towards more mainstream profiles. This trend is more evident when compared to participation in the 15M. In the mobilizations that took place between 2018 and 2019, including those of the 8M, despite an overrepresentation of critical and progressive profiles, the mainstream component is clear. The majority of individuals participating identify themselves with moderate center or left-wing political positions. The incorporation of newcomers contributes significantly to this moderation. Without a doubt, this is a notable normalizing effect of the 8M.

Finally, the results underline the importance of maintaining identity ties with the social movements underlying the protest (Melucci, 1995). These ties are present amongst both regulars and newcomers, and it may also be associated with the withdrawal or lack of continuity in the mobilizations. Furthermore, the relationship with the movement activity is also expressed in the association between participants (regulars and newcomers) and sympathy towards the 15M.

The results confirm the progress of the normalization of the profile of citizens taking to the streets to express their demands. If the 15M was characterized by its intergenerational nature, the 8M is distinguished by a lower urban bias and more diverse educational levels. This normalizing effect is especially noticeable in terms of age, with the inclusion of the youngest cohorts (compensating for the tendency towards an overrepresentation of young adults and adults) and, notably, of individuals with moderate political profiles.

This study suggests the political significance of events such as the 8M or, previously, the 15M or the mobilizations against terrorism, in which protests on the streets extends beyond the usual participant circles. Given their ability to attract broader participant groups, these mobilizations may be considered “normalizing events” of protest, which involve learning experiences and an expansion of the political repertoire for sectors of the population that are traditionally less active in extra-institutional politics, reducing participatory inequality.

In this sense, the research reveals an interest in paying specific attention to the process of the incorporation of conservative sectors in protest events. The growing recourse to protest by conservative and populist parties of the radical right, as occurring in the demonstrations linked to the unity of Spain, suggests a scenario of profound transformation in the presence of distinct groups in extra-institutional participation forms and the role of the street in the functioning of representative democracies.

Bibliography

Aelst, Peter van and Walgrave, Stefaan (2001). “Who Is that (Wo)man in the Street? From the Normalisation of Protest to the Normalisation of the Protester”. European Journal of Political Research, 39(4): 461-486. doi: 10.1023/A:1011030005789

Aguilar Fernández, Susana (2010). “El Activismo político de la Iglesia católica durante el gobierno de Zapatero (2004-2010)”. Papers. Revista de Sociología, 95(4): 1129-1155. doi: 10.5565/rev/papers/v95n4.174

Anduiza, Eva; Cristancho, Camilo and Sabucedo, José M. (2013). “Mobilization through Online Social Networks: The Political Protest of the Indignados in Spain”. Information, Communication & Society, 17(6): 750-764. doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2013.808360

Avendaño, Antonio (2018). “El 8M ha sido el 15M de las mujeres”. Elplural.Com, March 8. Available at: https://www.elplural.com/autonomias/andalucia/el-8m-ha-sido-el-15m-de-las-mujeres_121189102, access March 10, 2024.

Bellido, Indira (2019). “8M: la manifestación intergeneracional para celebrar el Día de la Mujer”. El Mundo, March 9. Available at: https://www.elmundo.es/yodona/lifestyle/2019/03/08/5c82ce7421efa08f278b4698.html, access March 10, 2024.

Berezin, Mabel (2017). Events as Templates of Possibility: An Analytic Typology of Political Facts. In: J. C. Alexander, R. N. Jacobs and P. Smith (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Cultural Sociology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195377767.013.23

Borbáth, Endre and Gessler, Theresa (2020). “Different Worlds of Contention? Protest in Northwestern, Southern and Eastern Europe”. European Journal of Political Research, 59(4): 910-935. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12379

Campillo, Inés (2019). “‘If We Stop, the World stops’: The 2018 Feminist Strike in Spain”. Social Movement Studies, 18(2): 252-258. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2018.1556092

Castells, Manuel (2015). Redes de indignación y esperanza. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

Dalton, Russel J. (2000). Citizen Politics. Public Opinion and Political Parties in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Washington: CQ Press.

Dalton, Russell J. (2008). “Citizenship Norms and the Expansion of Political Participation”. Political Studies, 56(1): 76-98. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2007.00718.x

Dean, Jonathan and Aune, Kristin (2015). “Feminism Resurgent? Mapping Contemporary Feminist Activisms in Europe”. Social Movement Studies, 14(4): 375-395. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2015.1077112

Della Porta, Donatella; Andretta, Massimiliano; Fernandes, Tiago; Romanos, Eduardo and Vogiatzoglou, Markos (2018). Legacies and Memories in Movements: Justice and Democracy in Southern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190860936.001.0001

El País (2019). “Las estudiantes lideran en las calles la protesta feminista del 8 de marzo”. El País, March 10. Available at: https://elpais.com/sociedad/2019/03/08/actualidad/1552041211_936244.html, access March 10, 2024.

Fishman, Robert M. (2011). On the Significance of Public Protest in Spanish Democracy. In: J. Jordana, V. Navarro, F. Pallarés and F. Requejo (eds.). Democràcia, política i societat: Homenatge a Rosa Virós. Barcelona: Universitat Pompeu Fabra. Deleatur, s.l.

Flesher Fominaya, Cristina (2020). Democracy Reloaded: Inside Spain’s Political Laboratory from 15-M to Podemos. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780190099961.001.0001

Galdón Corbella, Carmen (2020). Del movimiento 15M a la huelga feminista del 8M: un recorrido y algunas claves para entender el presente del movimiento feminista. In: R. Díez-García and G. Betancor-Nuez (eds.) Movimientos sociales, acción colectiva y cambio social en perspectiva: continuidades y cambios en el estudio de los movimientos sociales. Bizkaia: Fundación Betiko. Available at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7135150, access March 10, 2024.

Gallego, Aina (2007). “Unequal Political Participation in Europe”. International Journal of Sociology, 37(4): 10-25. doi: 10.2753/ijs0020-7659370401

Gil, Iván; Villarino, Ángel and Pascual, Alfredo (2018). “8-M histórico: millones de españolas llevan el feminismo al corazón del debate político”. El Confidencial, March 9. Available at: https://www.elconfidencial.com/espana/2018-03-09/8-m-historico-millones-feminismo-partidos-politicos_1532930/, access March 10, 2024.

Giugni, Marco and Grasso, Maria T. (2016). The Biographical Impact of Participation in Social Movement Activities: Beyond Highly Committed New Left Activism. In: L. Bosi, M. Giugni and K. Uba (eds.). The consequences of social movements. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781316337790.004

Grasso, Maria T. and Giugni, Marco (2019). “Political Values and Extra-institutional Political Participation: The impact of Economic Redistributive and Social Libertarian Preferences on Protest Behaviour”. International Political Science Review, 40(4): 470-485. doi: 10.1177/0192512118780425

Jann, Ben (2014). “Plotting Regression Coefficients and other Estimates”. Stata Journal, 14(4): 708-737. doi: 10.1177/1536867x1401400402

Jiménez-Sánchez, Manuel (2011). La normalización de la protesta el caso de las manifestaciones en España (1980-2008). Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Jiménez-Sánchez, Manuel; Pérez, Raúl and Betancor, Gomer (2021). “The Mobilization of Pensioners in Spain as a Process of Construction and Learning of a New Collective Identity”. Empiria. Revista de Metodología de Ciencias Sociales, 52: 97-124. doi: 10.5944/EMPIRIA.52.2021.31366

Jiménez-Sánchez, Manuel; Fraile, Marta and Lobera, Josep (2022). “Testing Public Reactions to Mass-protest Hybrid Media Events: A Rolling Cross-sectional Study of International Women’s Day in Spain”. Public Opinion Quarterly, 86(3): 597-620. doi: 10.1093/POQ/NFAC033

Jiménez-Sánchez, Manuel and García-Espín, Patricia (2023). “The Mobilising Memory of the 15-M Movement: Recollections and Sediments in Spanish Protest Culture”. Social Movement Studies, 22(3): 402-420. doi: 10.1080/14742837.2022.2061941

Klingemann, Hans-Dieter (2015). Dissatisfied Democrats: Democratic Maturation in Old and New Democracies. In: R. Dalton and C. Welzel (eds.). The Civic Culture Transformed: From Allegiant to Assertive Citizens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139600002.010

Kostelka, Filip and Rovny, Jan (2019). “It’s Not the Left: Ideology and Protest Participation in Old and New Democracies”. Comparative Political Studies, 52(11): 1677-1712. doi: 10.1177/0010414019830717

Marien, Sofie; Hooghe, Marc and Quintelier, Ellen (2010). “Inequalities in non-institutionalised forms of political participation: a Multi-level Analysis of 25 Countries”. Political Studies, 58(1): 187-213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

McAdam, Doug (1986). “Recruitment to High-Risk Activism: The Case of Freedom Summer”. American Journal of Sociology, 92(1): 64-90. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2779717, access March 10, 2024.

Melucci, Alberto (1995). The Process of Collective Identity. In: H. Johnston and B. Klandermans (eds.). Social Movements and Culture. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.ctttt0p8.6, access March 10, 2024.

Norris, Pippa (2011). Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511973383

Norris, Pippa; Walgrave, Stefaan and Aelst, Peter van (2005). “Who Demonstrates? Antistate Rebels, Conventional Participants, or Everyone?”. Comparative Politics, 37(2): 189-205. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20072882, access March 10, 2024.

Opp, Karl-Dieter (1990). “Postmaterialism, Collective Action, and Political Protest”. American Journal of Political Science, 34(1): 212-235. doi: 10.2307/2111516

Pavan, Elena (2020). Women’s Activism. In: The International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media and Communication. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. doi: 10.1002/9781119429128.iegmc049

Romero, Juanma (2019). “El 8-M sigue creciendo: más de 550.000 manifestantes entre Madrid y Barcelona”. El Confidencial, March 8. Available at: https://www.elconfidencial.com/espana/2019-03-08/feminismo-movilizaciones-dobla-cifras-record-historico-28-a_1871382/, access March 10, 2024.

Sánchez Hidalgo, Emilio (2018). “El 8-M también fue histórico en los pueblos de España”. El País, March 10. Available at: https://verne.elpais.com/verne/2018/03/10/articulo/1520701788_296853.html, access March 10, 2024.

Saunders, Clare and Shlomo, Natalie (2021). “A New approach to Assess the Normalization of Differential Rates of Protest Participation”. Quality and Quantity, 55(1): 79-102. doi: 10.1007/s11135-020-00995-7

Torcal, Mariano; Rodon, Toni and Hierro, María J. (2016). “Word on the Street: The Persistence of Leftist-dominated Protest in Europe”. West European Politics, 39(2): 326-350. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2015.1068525

Verba, Sidney (2003). “Would the Dream of Political Equality Turn out to Be a Nightmare?”. Perspectives on Politics, 1(4): 663-679. doi: 10.1017/S1537592703000458

Verba, Sidney; Schlozman, Kay L. and Brady, Henry E. (1995). Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1pnc1k7

Watkins, Susan (2018). “Which Feminisms?”. New Left Review, 109: 5-76.

Annex

TABLE A1. Information on the variables in the analysis

|

Variables

|

Description

|

Response options

*and frequencies (%)

|

Survey questions

|

|

Type of event variables

|

Participa_ciclo

|

Participation in the 8M protests in 2018 or 2019

|

0. no: 69.12

1. yes: 30.88

|

P12

P14

|

|

otramani

|

Participation in protests over past 12 months (2018-2019)

|

0. no: 73.32

1. yes: 26.68

|

P16

|

|

par_15M

|

Participation in the 15M protests

|

0. no: 86.55

1. yes: 13.45

|

P17C

|

|

Type of 8M participant variables

|

exp8M

|

Participation experience in the 8M cycle (2018-2019)

|

1. regular: 15.98

2. new: 14.11

3. Ex-participant: 5.33

4. Non participant: 64.58

|

P12

P14

P15

|

|

Dependent variables

|

sexo

|

|

0. female: 51.51

1. male: 48.49

|

P22

|

|

cohorte

|

Decade of birth

|

1. 30s-40s: 9.32

2. 50s: 17.0

3. 60s: 22.63

4. 70s: 21.36

5. 80s: 15.07

6. 90s-2001: 14.62

|

P23 (age)

(range 18-91)

|

|

habitat

|

Size of municipality of residence

|

1.< 10 thousand: 19.31

2. 10-<50: 24.03

3. 50-<100: 12.74

4. 100 -<25: 17.04

5. 250-<600: 9.31

6. >600 thousand: 17.58

|

P26

|

|

estudios

|

Level of completed studies

|

1. < = primary school: 10.15

2. secondary school: 28.53

3. secondary school: 27.14

4. higher secondary education: 34.18

|

P25

|

|

rrss

|

Frequency of use of social media, social or political activities

|

1. does not use: 59.74

2. sporadic: 13.62

3. regular: 26.63

|

P21A

(scale 1-5)

|

|

ideologia

|

Self-positioning on ideological scale

|

0. no comment/not situated: 12.27

1. far left (0-2): 10.2

2. center-left (3-4): 23.15

3. center (5): 34.12

4. center-right (6-7): 12.53

5. far-right: 7.73

|

P18

(scale 0-10)

|

|

ipca

|

Interest in politics

|

1. none: 18.58

2. little: 33.49

3. considerably: 31.85

4. a lot: 16.08

|

P01

(scale 1-4)

|

|

scd

|

Satisfaction with functioning of democracy

|

1. unsatisfied (0-5): 58.46

2. satisfied (6-10): 41.54

|

P03

(scale 0-10)

|

|

sim_movfem

|

Sympathy with feminist movement

|

0. no (1-3): 32.38

1. yes (4-5): 67.62

|

P11D

(scale 1-5)

|

|

simp_15M

|

Sympathy with the 15M movement

|

0. no comment/does not sympathize (0-5): 61.33

1. sympathizes (6-10): 38.67

|

P17B

(scale 0-10)

|

TABLE A2. Summary table of logistic regression models. Participation in three types of events

|

8M (2018-2019)

|

others (2018-2019)

|

15M

|

|

Gender (ref. woman)

|

|

Man

|

0.374***

[0.0416]

|

0.937

[0.101]

|

1.516**

[0.230]

|

|

Cohort (ref. 1990s-2001)

|

|

30s-40s

|

0.399***

[0.106]

|

0.942

[0.243]

|

1.249

[0.545]

|

|

50s-70s

|

0.582***

[0.0860]

|

1.183

[0.185]

|

2.346***

[0.543]

|

|

80s

|

0.629*

[0.115]

|

1.079

[0.207]

|

2.279**

[0.620]

|

|

Habitat (ref. >600 mil)

|

|

<10 mil

|

0.668*

[0.119]

|

0.692*

[0.119]

|

0.351***

[0.0896]

|

|

10-<50 mil

|

0.613**

[0.103]

|

0.905

[0.146]

|

0.479**

[0.107]

|

|

50-<600 mil

|

0.867

[0.129]

|

0.871

[0.128]

|

0.732

[0.143]

|

|

Education (ref. university)

|

|

primary school

|

0.635

[0.161]

|

0.613*

[0.144]

|

0.476

[0.186]

|

|

secondary school

|

0.865

[0.123]

|

0.818

[0.114]

|

0.557**

[0.113]

|

|

higher education

|

0.858

[0.115]

|

0.766*

[0.103]

|

0.758

[0.135]

|

|

Social media (ref. regular use)

|

|

Does not use

|

0.465***

[0.0590]

|

0.500***

[0.0634]

|

0.362***

[0.0626]

|

|

Sporadic

|

0.515***

[0.0861]

|

0.689*

[0.116]

|

0.511**

[0.116]

|

|

Ideology (ref. left-wing)

|

|

undetermined

|

0.278***

[0.0603]

|

0.426***

[0.0895]

|

0.350***

[0.101]

|

|

center(5)

|

0.430***

[0.0546]

|

0.476***

[0.0610]

|

0.201***

[0.0375]

|

|

Right-wing (6-10)

|

0.212***

[0.0349]

|

0.332***

[0.0516]

|

0.0795***

[0.0251]

|

|

Political interest (ref. interested)

|

|

Little/None

|

1.582***

[0.190]

|

1.798***

[0.213]

|

2.300***

[0.391]

|

|

Dem. satisfaction (ref. unsatisfied)

|

|

Satisfied (6-10)

|

0.944

[0.105]

|

0.684***

[0.0770]

|

0.537***

[0.0834]

|

|

Observations

|

2031

|

2034

|

2030

|

|

Pseudo R-squared

|

|

|

|

Exponentiated coefficients; Standard errors in brackets.

* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Source: Author’s own creation based on the PROTEiCA 2019 survey. Available at: https://www.upo.es/investiga/ptyp/encuestaproteica2019/

TABLE A3. Summary of logistic regression models. Comparisons of regular participants with newcomers,

former participants and non-participants in 8M (2018-2019)

|

Newcomers

|

ex-participants

|

non participants

|

|

Gender (ref. woman)

|

|

|

|

|

Man

|

1.286

|

2.288**

|

3.171***

|

|

[0.235]

|

[0.594]

|

[0.489]

|

|

Cohort (ref. 1990s-2001)

|

|

|

|

|

30s-40s

|

0.512

|

3.469*

|

1.144

|

|

[0.241]

|

[1.926]

|

[0.439]

|

|

50s-70s

|

0.619*

|

1.623

|

1.069

|

|

[0.139]

|

[0.601]

|

[0.238]

|

|

80s

|

0.698

|

0.649

|

1.194

|

|

[0.203]

|

[0.342]

|

[0.315]

|

|

Habitat (ref. >600 mil)

|

|

|

|

|

<10 000

|

0.578

|

1.471

|

1.326

|

|

[0.175]

|

[0.622]

|

[0.319]

|

|

10-<50 000

|

1.009

|

1.042

|

1.715*

|

|

[0.275]

|

[0.443]

|

[0.420]

|

|

50-<600 000

|

0.948

|

1.335

|

1.078

|

|

[0.225]

|

[0.498]

|

[0.226]

|

|

Education (ref. university)

|

|

|

|

|

1. primary school 0

|

0.666

|

1.037

|

2.018

|

|

[0.308]

|

[0.604]

|

[0.731]

|

|

2. secondary school

|

0.577*

|

0.469*

|

0.977

|

|

[0.137]

|

[0.173]

|

[0.185]

|

|

3. higher education

|

1.237

|

1.374

|

1.337

|

|

[0.268]

|

[0.437]

|

[0.257]

|

|

Social media (ref. regular use)

|

|

|

|

|

Does not use

|

1.221

|

0.737

|

2.761***

|

|

[0.253]

|

[0.231]

|

[0.486]

|

|

Sporadic

|

1.077

|

0.844

|

2.462***

|

|

[0.295]

|

[0.318]

|

[0.540]

|

|

Ideology (ref. left-wing)

|

|

|

|

|

undetermined

|

2.046

|

3.794*

|

4.066***

|

|

[0.875]

|

[2.006]

|

[1.451]

|

|

center(5)

|

1.656*

|

1.757

|

2.147***

|

|

[0.356]

|

[0.591]

|

[0.388]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Right-wing(6-10)

|

1.622

|

1.800

|

3.690***

|

|

[0.463]

|

[0.730]

|

[0.906]

|

|

Political interest (ref. interested)

|

|

|

|

|

Little/None

|

1.353

|

1.861*

|

1.572**

|

|

[0.277]

|

[0.583]

|

[0.265]

|

|

Dem. satisfaction (ref. unsatisfied)

|

|

|

|

|

Satisfied (6-10)

|

1.184

|

1.670

|

1.189

|

|

[0.214]

|

[0.440]

|

[0.184]

|

|

Sympathetic with feminist movement (ref. does not sympathize)

|

|

|

|

|

Fem mov. sympathizer=1

|

1.069

|

0.494*

|

0.313***

|

|

[0.283]

|

[0.170]

|

[0.0669]

|

|

Sympathetic with 15M (ref. unknown/does not sympathize)

|

|

|

|

|

Sympathizer (6-10)

|

0.938

|

0.689

|

0.547***

|

|

[0.188]

|

[0.202]

|

[0.0926]

|

|

Observations

|

586

|

409

|

1574

|

|

Pseudo R-squared

|

|

|

|

Exponentiated coefficients; Standard errors in brackets.

* p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001.

Source: Author’s own creation based on the PROTEiCA 2019 survey. Available at: https://www.upo.es/investiga/ptyp/encuestaproteica2019/