A Cultural Gap? Perceptions

of the Armed Forces Held by Spanish Political, Economic and Military Elites

¿Brecha cultural? Percepciones de elites políticas, económicas

y militares españolas respecto de las Fuerzas Armadas

Alberto Bueno, Marién Durán and Rafael Martínez

|

Key words Armed Forces

|

Abstract The existence or otherwise of a culture gap between military elites and civilian elites (that is, convergence or divergence in values and perceptions between these elites regarding military administration) can hinder defence policy. This research examines the perceptions about the Armed Forces held by three groups of Spanish elites (political, business and military), based on 46 in-depth structured interviews and 93 survey respondents, to verify the existence of such a gap. The analysis addresses two dimensions: a) shared values between the military, society and political decision-makers; b) social perceptions. The main findings of this study are: a) some social stereotypes are also reproduced among the elites. b) the military elites exhibit a greater convergence with the economic elites than with the political elites. |

|

Palabras clave Fuerzas Armadas

|

Resumen La existencia, o no, de una brecha cultural entre elites militares y elites civiles, es decir, la convergencia o divergencia en valores y percepciones entre dichas elites respecto a la administración militar, puede dificultar el desarrollo de la política de defensa. Esta investigación examina las percepciones de tres grupos de elites españolas (políticas, empresariales y militares) sobre las Fuerzas Armadas, a partir de 46 entrevistas estructuradas en profundidad y 93 encuestados, para comprobar la existencia de dicha brecha. El análisis aborda dos dimensiones: a) valores compartidos entre institución castrense, sociedad y decisores políticos; b) percepciones sociales. Los principales resultados de este trabajo son: a) algunos de los tópicos sociales se reproducen también entre las elites; b) las elites militares muestran una mayor convergencia con las económicas que con las políticas. |

Citation

Bueno, Alberto; Durán, Marién; Martínez, Rafael (2025). «A Cultural Gap? Perceptions of the Armed Forces Held by Spanish Political, Economic and Military Elites». Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 189: 5-22. (doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.189.5-22)

Alberto Bueno: Universidad de Granada | albertobueno@ugr.es

Marién Durán: Universidad de Granada | mduranc@ugr.es

Rafael Martínez: Universidad de Barcelona | rafa.martinez@ub.edu

Introduction1

Interactions between political and military elites have a strong impact on shaping the social perceptions of military and defence issues (Kertzer and Zeitzoff, 2017: 544-545; Golby, Feaver and Dropp, 2018), as well as on how security and defence policies are articulated (Chaqués-Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner, 2015; Mathieu, 2015). The state of civil-military relations (hereafter CMR) is therefore a key aspect of defence policy.

CMR have been understood for decades as a space of confrontation between the two elites over whether political leaders would take control of defence policy and the Armed Forces (hereafter, AFs). However, numerous studies have shown that CMR transcend this dichotomy, as they constitute a system in which three actors interact: the politicians, the military and society (Fitch, 1998; Barany, 2012; Pion-Berlin and Martínez, 2017). Relations between the latter two have led them to share some views on policy and the political system (Janowitz, 1960). Therefore, having AFs that are distanced from their social fabric in terms of their extraction, ideas, values, etc., would be a bad symptom for the CMR. Moskos and Wood (1988) called these bonds “an external integration of the armed forces”, implicitly referring to social legitimacy.

The need to converge with society does not mean that the AFs lose their internal integration; that is, the traits and bonds that facilitate group cohesion, their ethos. In fact, the military has traditionally handled codes and values that are different from those of society. In post-modern societies, however, the trend has been the opposite: the blurring of the boundaries between civilian and military, with increased permeability between the two and the weakening of martial values that are alien to social values (Allen and Moskos, 1997).

Nevertheless, convergence is not only about an approximation in values between society and its AFs, namely, civilianization (Janowitz, 1960) as opposed to professionalism (Huntington, 1957). This dimension covers all those aspects that can bring the two worlds closer together or drive them apart. This interaction between civilians and the military has a structural (socio-political) aspect, an institutional aspect and an ideational aspect, the latter referring to the more subjective and cultural aspects of human action (Kuehn and Lorenz, 2011; Levy, 2012). The literature has therefore focused on whether or not a culture gap exists between civilian and military (Collins and Holsti, 1999; Feaver and Kohn, 2001; Nielsen, 2022; Feaver, 2003; Szayna et al., 2007; Rahbek-Clemmensen et al., 2012).

In post-Franco Spain, the crucial objective was to establish civilian supremacy in CMR (Serra, 2008), which was achieved in the late 1980s. Once this had been achieved, interest in examining how the AFs were controlled waned (Bueno, 2019). However, this did not apply to the analysis of the mismatch between the military and society, which revealed high levels of rejection and critical stances towards the military and defence policy, with important territorial and ideological cleavages. The prevailing negative and low-prestige image of the AFs was the main object of study (Díez-Nicolás, 1986, 1999, 2006; Martínez and Díaz, 2007; Martínez, 2008; Cicuéndez Santamaría, 2017; Martínez and Durán, 2017; Navajas, 2018; Calduch, 2018; Martínez, 2020; Martínez and Padilla, 2021). The series of surveys on the AFs and society conducted between 1997 and 2017 by the Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS) contributed to this2.

In contrast, our research concern here emerged from the realisation that few studies have investigated the potential gap between the elites involved in the development and implementation of defence policy (Martínez and Díaz, 2005; Caforio, 2007). The aim of this paper is therefore to test whether there is a culture gap between the military and civilian elites in Spain, as hypothesised here.

By elites we mean, broadly speaking, those who hold and exercise power (Scott, 2008), referring specifically to defence policy: political and military elites. Nonetheless, we have also included the economic elites of the defence industry as interacting actors in this system. The development of this policy is influenced by international, economic and social factors which are both circumstantial and structural, where the interests of these three elites compete with each other: on the one hand, the, economic and political elites, which we have called the civilian elites; and on the other, the military elite, comprising the high commanders of the military and defence staffs.

This research draws on qualitative and quantitative data generated by a 2020-2024 research project conducted by the Spanish Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigación), entitled “Rethinking the Role of the Armed Forces in the Face of New Security Challenges” (Repensando el papel de las Fuerzas Armadas ante los nuevos desafíos a la seguridad (REPENFAS21)). The article is structured, first of all, by delving into the theoretical framework of the culture gap. It then sets out the main characteristics of CMR in Spain in order to establish a contextual frame of reference and, subsequently, detail the research methodology. The fourth section presents the results of the analysis based on the different variables proposed, and finally, the conclusions and future avenues of research.

The concept of CMR has been, and continues to be, widely debated in the literature. According to Nielsen and Sneider (2009: 3), it encompasses different types of relationships:

- Between the military institution and society at large.

- Between the military and the political-administrative level of the state.

- Between military leaders and their organisations within the AFs themselves. Without ignoring the importance of the latter and its relevance when analysing organisational culture, the first two show the territories in which the culture gap may reside.

It is assumed that CMR will be more complicated the wider the gap between the two worlds (greater institutional autonomy, greater political influence, highly differentiated social values, etc.). However, the concept of gap does not have a unanimously accepted definition either, although common attributes such as cultural aspects can be identified: whether the values broadly upheld by civilians and the military differ or converge (Rahbek-Clemmensen et al., 2012; Cohen and Cohen, 2022).

In this paper, the term culture is addressed from both a sociological and a political science approach. The sociological approach refers to a:

System of conceptions expressed in symbolic forms, by means of which people communicate, perpetuate and develop their knowledge about attitudes towards others and the world (Geertz, 1997: 19).

It therefore affects a complex web of experiences, values and expectations that may vary within the same cultural environment, manifested through different interpretations of reality. The political science angle relies in an idea of political culture which looks at attitudes and opinions on, and orientations towards, political objects and institutions regarding defence, the configuration of which may differ among different social groups (Bueno et al., 2023).

This raises the question of how the organisational culture of the military administration and the political culture of the citizens coexist, as it is not uncommon to hold a disdainful or stereotypical view of the other, motivated by mutual ignorance. Closing or bridging the gap requires that both parties understand, value and respect each other (Martínez, 2024). The values upheld by elites are determined by the organisational culture, the processes to socialise norms, and the existing trajectories within the organisation and group perceptions. Organisational culture thus shapes the interpretation of contexts and, ultimately, the behaviour of the strategic core (Mintzberg, 2012).

The military is an institutionalised social group, subject to the state and its legal system. This institution has internalised values such as sacrifice, unity and discipline, as with an strongly hierarchical chain of command (Huntington, 1957) in which orders are formally conveyed. Their actions are determined by military rules, underpinned by values in which members have been socialised in military academies, doctrines and operational procedures. This generally takes place through training (Ruffa, 2017: 394).

Differences or similarities in values between the two groups have been studied by relating politicians and military, and military and civil society (Avant, 1988; Cohen, 2000; Forster, 2012; Rahbek-Clemmensen et al., 2012). Avant (1988) analysed whether the military is representative of society, its values or its geographical diversity, and whether this prevents it from becoming a kind of social stratum. In this regard, she concluded that CMR would be healthier the more the AFs resemble the society from which it draws and which it serves. In his analysis of the degree of autonomy that the military has, and of the influence of civilian and military decision-makers in the policy-making process (especially in those related to the use of force), Cohen (2000) emphasised the relationship between values, military culture and social culture. Rahbek-Clemmensen et al. (2012) highlighted two gaps3:

- The cultural gap, referred to whether the attitudes and values of the civilian and military population differ.

- The demographic gap: whether or not the military represents the population in its partisan and socio-economic composition.

Regarding the cultural gap, they pointed to mutual perceptions, normative socialisation processes and organisational trajectories as analytical variables; regarding the demographic, they referred to geographical origins, ethnicity, political affiliation and family or socio-economic background.

In turn, Forster (2012) identified two gaps: the expectation-commitment gap and the respect-value gap. The first referred to the mismatch between the demands of the missions assigned to the AFs and the resources that governments are willing to provide to carry them out. The second gap explained that citizens respect, but do not value, the sacrifice of those who put themselves in harm’s way to serve their country. He therefore called for a (desirable) convergence of values between both elites, based on the assumption of a (necessary) representativeness in values, culture and pluralism of the AFs with respect to society.

Thus, depending on how the political elite and the military elite perceive values, the effectiveness of CMR can be undermined and affect cooperation, coordination and collaboration between the two (Feaver and Kohn, 2000: 29). This relationship between the military expert and the minister has been described as a modern CMR problem (Huntington, 1957; Bland, 1999) and as one of the main factors in understanding the functioning of defence ministries (Mukherjee and Pion-Berlin, 2022). This link between political leaders and their military advisors can either be based on trust, or marked by mistrust between those who are uninformed and those who know.

When Bland (1999) proposed the “expert problem”, he argued that the minister, through ordinary dealings with military high commands, should create an atmosphere of trust and respect for their views, as this would facilitate consensus building with experts. The minister must also demand loyalty and make it clear that it is the minister who makes the decisions and is accountable to the people. If the military is to serve and advise democratic governments, “they need to develop a broader mindset, one that is supportive of democratic rule, foreign policy, and civilian control” (Mukherjee and Pion-Berlin, 2022: 789). Consequently, military and civilian values should converge to avoid creating a gap that could lead to irresolvable problems.

It can be inferred from the above that, in order to measure the quality or health of CMR, the literature generally points to the existence of a gap which can be called a cultural gap, to use the term used by Geertz (1997), which consists of two dimensions:

- One refers to shared values, of convergence or divergence between the military, society and political decision-makers.

- The other is related to the existing perceptions of the military.

Civil-military relations

in Spain

In the case of Spain, the changes that have taken place over the last forty years have brought about some positive developments that have reduced the culture gap. However, it should be remembered that, in 1986, once democracy had been fully established and Spain had become a member of the European Union, the country still faced important challenges with regard to the military. One of them was to build positive CMR. It was not for nothing that the Spanish military was not socially well regarded: 47 % of young people believed that AFs members were useless and 37 % that they were skilled4. The military had also garnered negative political perceptions, as society identified the army with Francoism. During the 1980s and 1990s, the AFs were the least trusted institution (data from the European Value Systems Study Group collected by Villalaín Benito, 1992: 284), with 39 % of Spaniards and 57 % of young people perceiving them as being technically deficient and unable to defend Spain from an attack by another country. By contrast, 35 % of all Spanish people and 29 % of young people believed that they were able to defend Spain5. Furthermore, the significant presence of US bases and troops on Spanish soil did nothing to reduce this trend. In 1989, membership of the military held a poor reputation among Spaniards, while 42 % of conscripts found the experience of compulsory military service unpleasant6. In 1990, political parties were the only institution rated lower than the AFs.7 Nevertheless, Spanish society was not pacifist; rather, it possessed traits of an anti-militarism that was more visceral than rational (Martínez and Díaz, 2005). As society was far removed from the AFs, successive governments postulated the need to promote a political defence culture (Martínez, 2007a).

Public opinion has gradually improved since the end of the 1990s, to the extent that in 2015 the Civil Guard (Guardia Civil), the National Police (Policía Nacional) and the Armed Forces were the three most highly valued institutions in the Spanish political system8. There were several factors involved in this change: the widespread discredit of politics, legal and institutional reforms, greater historical distance from the 1981 coup d’état, the decline of the US military presence, the abolition of compulsory military service, the decline of military inbreeding, the absence of corruption scandals in the military administration and, above all, the positive social impact of the international missions carried out by the AFs (Martínez and Durán, 2017: 2). Redirecting the focus of the Spanish military from the domestic to the foreign context was thus the key turning point for this change in trend (Martínez, 2007: 228)9. It can be stated that at the beginning of the third decade of the 21st century (Martínez, 2020, 2022; Martínez and Padilla, 2021; Bueno et al., 2023):

- Being a member of the AFs is a profession held in low esteem; however, non-traditional recruitment channels have now become socially internalised and society accepts the distinct military ethos.

- The current model of AFs exhibits a small and well-prepared force, which is considered to be expensive. In fact, while society sees the AFs as being increasingly better trained and equipped and perceives the volume of personnel to be adequate, the public does not wish to increase the economic resources allocated to the military.

- Society approves of the new AFs missions (international operations, intervention in catastrophes and disasters, etc.). Nevertheless, although the public believes the military are suitably prepared to defend Spain, a good part of civil society has difficulties in accepting the most traditional functions of national defence, namely, territorial defence and deterrence.

- The Spanish military suffers from cognitive dissonance: they believe they enjoy neither the trust nor the respect of their fellow citizens; in contrast, society generally holds the AFs in high regard, and perceives them as a factor of international prestige and as being removed from any claims to political leadership in the country.

- Society does not want to abolish the AFs, but wants greater European (multilateral) integration of defence policy.

To test the hypothesis posed in this paper on whether there is a culture gap between civilian and military elites, qualitative and quantitative data obtained in REPENFAS21 research project was used. We began by compiling a list of the main items on defence and the Armed Forces in institutional documentation and selecting questions on these issues that have been asked in different studies, preferably by the CIS (see Annex 1 for a complete list of documents and questionnaires)10.

Based on this systematic review, four thematic blocks (external action, social views of the Armed Forces, the Armed Forces themselves and the institutional structures of national security) were identified. These included the (approximately) fifty questions that were used to operationalise the items that made up the questionnaire (Annex 2) for the in-depth structured interviews with the elites11. The interviews were conducted between May and November 2021. Three groups of elites were interviewed:

- 14 of the 17 selected executives from leading Spanish companies in the main sectors of the defence industry (Annex 6.1).

- 20 admirals and generals from the General Staffs of the three armies and Defence; as well as senior military commanders from the Ministry of Defence (Annex 6.2).

- 12 of the 20 parliamentary spokespersons of the 14th parliamentary term in the Defence Committees of the Spanish Congress and Senate (Annex 6.3).

All interviews were conducted face-to-face. The more than 60 hours of recordings were transcribed by a company called Amberscript into 728 pages. The coding and analysis of all transcripts was carried out by two members of the research team to avoid bias and divergences in interpretation. Interview transcripts were analysed using R-based text analysis techniques (R Core Team, 2023), with the libraries quanteda (Benoit et al., 2018) and topicmodels (Grün and Hornik, 2011). Latent Dirichlet allocation was used for topic modelling.

In order to guarantee the anonymity of the respondents and be able to directly refer to extracts of their answers, the references “Politician/Executive/Military member” and the number assigned in the coding were indicated12.

To quantitatively strengthen the qualitative evidence extracted from the interviews, the Qualtrics software was used to apply an online closed, self-administered questionnaire between December 2021 and January 2022. The respondents were (Annex 7) all the colonels who were taking the training course to become generals in January 2022 (n=70)13 and the other parliamentarians of the aforementioned parliamentary commissions (29 senators and 55 congresspeople). Responses were obtained from 100 % of the participants from the military and 27 % from the members of the parliament, primarily from the popular party and socialist groups. After the entire interview and survey process was completed, war broke out in Ukraine. We thus had the opportunity to launch a natural experiment, namely, to ask the 46 interviewees only those questions that we considered likely to have different answers due to the impact of the conflict (Annex 8)14.

These responses were used to conduct an exploratory descriptive analysis that might possibly show the existence of a culture gap, which would provide a wide range of nuances and point to vectors towards which a subsequent explanatory study could be directed by relying on the qualitative evidence obtained. It is worth noting that the low response rate from the parliamentarians surveyed and also from the experiment conducted with interviewees suggested that these data should not be taken into account. However, given the extreme difficulty in interviewing or surveying these elites on these issues, and assuming the scientific weakness of these specific contributions, it was decided not to discard them.

The thematic block of questions that the interviews and surveys asked about social views on the AFs led to six variables being selected to analyse the potential culture gap between the elites, across two dimensions. One variable, preferred values for a child and for a member of the Armed Forces, completed the first dimension, while the other five variables: namely,

- Training.

- Social cohesion.

- Pluralism.

- Social image.

- Prestige, made up the social perception dimension.

Regarding the first variable, it was essential to assess the convergence in values between society and its military administration in order to understand the processes involved in civil-military relations. The questions focused on the essentials in military training and in their son/daughter’s education as an indirect way of asking about the social desirability of certain values. This showed whether the members of the Armed Forces wanted differentiated values for themselves and their children, whether the same was true for the other two groups of elites, and whether the elites held similar or dissimilar views.

The professional training variable reproduced (with no changes) the question from the CIS questionnaires asking whether training enables AFs members to carry out their work effectively. Social cohesion refers to whether young people providing a service (whether social or in the Armed Forces) could be a vehicle for socialisation, for transmitting collective values that promote a culture of commitment and unity that generates national integration.

The question of whether or not armies should reproduce a country’s linguistic, political and religious diversity (in short, its plurality) lies in the idea of convergence or divergence. Spain’s social plurality focuses on linguistic, religious and political diversity. It sought to ascertain whether the AFs reflect this plurality, both descriptively and normatively; that is, whether they already do and, if they do not, whether they should.

The social image variable was not operationalised by asking respondents about their own perception, but about the image they believed that society, the elites and the media have of the AFs. Moreover, given Spanish society’s difficulty in accepting strictly defence missions, the impact on the military’s image of two recent actions not linked to classic national defence missions but to catastrophes and calamities was also investigated. These were their interventions in the severe winter storms of 2021 and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, delving deeper into the social vision of the armed forces, we examined whether the military profession is considered a prestigious profession; and if the answer was in the negative, what were the reasons for the lack of prestige.

The results obtained confirmed the hypothesis of the existence of a culture gap between elites. However, the analysis by dimensions that we proposed showed that this gap was almost non-existent in the dimension of values and became more visible in the aspects that were related to the dimension of social perception.

The elites interviewed diverged in the values they wanted a member of the military to have and those they wanted for their children. Therefore the divergence between society and its military administration prevailed. However, contrary to what this first statement suggests, there was a general convergence on values, as military, political and economic elites substantially agreed on the values they wanted their children to have and the values they wanted for a member of the military to uphold. Thus, while they agreed that the values should be different, at the same time they concurred on what these values should be. This is something that we have already observed to be generally the case for the future Spanish civilian and military elites (Martínez, 2007: 145-148).

In general, they all identified the following values as being socially desirable for their children: service to others, sacrifice and commitment. Nevertheless, there were some peculiarities in the preference for second and third order values. Loyalty and comradeship were deemed to be important as values for the military; politicians reiterated respect and called for democratic values; while executives pointed to a sense of authority as being important (Table 1).

There was also substantial agreement among the three elites on what values the military should develop in their training and in carrying out their duties (Table 2). For politicians, respect was the most frequently cited value, which may be indicative of some suspicion of military insubordination to civilian authority. For the military, loyalty was essential, while executives pointed to discipline. The three elites identified discipline and loyalty as values to be expected of military personnel, consistent with their training and ethos.

At the same time, more closely linked to their institution, the military placed great importance on the idea of service, sacrifice and comradeship. The respondents from the business elites emphasised a sense of duty, professionalism and patriotism. None of the three social groups emphasised “epic” values, although the idea of sacrifice could fit into this category. This would bring us closer to the argument of a “post-heroic” society (Luttwak, 1995).

On the other hand, the colonels and other parliamentarians had a similar approach to the values expected of a military member and, in fact, discipline and loyalty were emphasised by both groups (Figure 1). The same could be said for responsibility, patriotism and comradeship (again there was agreement between interviewees and survey respondents). Team spirit and honesty also featured prominently. This figure shows that the military and political elites also agreed on which values were less important to them: creativity, open-mindedness and a spirit of equality. In fact, only two values were rated differently: initiative and generosity.

Figure 1. Core values to be upheld by military members, according to the surveyed elites (%)

Note 1: The list of values was a closed list that resulted from the questionnaire.

Note 2: Thin lines represent 95 % confidence intervals.

Source: Developed by the authors.

In short, the results of the values dimension showed a weak gap, with shared visions of an ideal of citizenship. Despite agreement on the main points, there were slight nuances on the values expected of army professionals. While military members and businesspeople stressed values that were important for organisational performance, political representatives pointed to values that would highlight the strength of Huntington’s theory of CMR (sacrifice, discipline, etc.).

There was unanimity among the elites interviewed and surveyed that they considered the Spanish military to be remarkably well-qualified professionals. An assessment that contrasts with the meagre prestige associated with the military profession, with the fact that its social image has not improved as much as has been believed by taking on more socially significant tasks (pandemics, fires, snowfalls, volcanic eruptions) and with the notable social ignorance of what this profession entails. Consequently, there does not appear to have been a gap between civilian and military elites on this issue.

The only divergence from the general sentiment was found among the spokespersons of the parliamentary groups of the peripheral nationalist parties, albeit for different reasons. The first divergence arises from a democratic mistrust: “provided that the minimum democratic standards for an army in a democratic country are in place in this institution” (Politician 3). The second refers to the type of missions they carry out, mainly humanitarian or emergency missions: “although quite a few do not fit their professional expertise the AFs have still been used in these situations” (Politician 5).

They also pointed to “a lack of technical and material resources that undermine training” (Businessperson 3), and the lack of training due to the impossibility of being deployed in real scenarios and, consequently, of testing their training in the field:

[...] the problem is the decrease in resources available. This means that we have a problem in advanced training, coaching and preparation. The problem will come if we have to go into combat (Military Officer 8);

“there may be poorer performance as a result of the loss of capabilities that can influence training and preparedness” (Military Officer 17). Finally, a very uneven preparation within the army was noted, with the result that “only a small part of the military is really prepared for combat” (Businessperson 11).

The military and economic elites perceived a greater need to promote social cohesion measures; that is, to bring society closer to and be more aware of the work of the Armed Forces. However, the majority of respondents stated that establishing political measures in this direction (re-establishing military service, as was the case in Germany, or implementing civilian service models, as was done in France) is unfeasible due to the political and institutional context, and to social rejection:

I don’t think we will see that here [in Spain], it would be unfeasible, above all due to the lack of national identification and common values of some groups (Military Officer 8).

However, several military members held the view that the AFs should not be responsible for these kinds of actions:

I welcome the objective of contributing to greater cohesion, even the opportunity to involve the whole of society in producing something concrete, specific and standardised within society itself. But I don’t think is that this is a responsibility of the army (Military Officer 15).

This need was not so strongly demanded by political elites; they even considered it counterproductive. This was not unexpected, given that the analysis of the other thematic blocks in our interviews and surveys revealed that, in general, they lack key knowledge of national security and defence issues, and have a low interest in, and a not particularly favourable opinion of, the Armed Forces.

The military elites in the study believed that the AFs already reflect the pluralism of Spanish society, although they confined this to religious pluralism. They thought primarily of members who profess the Islamic religion, or of those who are either agnostic or atheist. Regarding AFs members who are Muslims, this was significant because it is the case in the military sites of the cities of Ceuta and Melilla. As far as AFs members who are either agnostic or atheist, this referred to the strong Catholic roots of the armies in Spain, where some ritual ceremonies are still conducted within a Christian liturgy, something that is difficult to reconcile with the non-confessional status of Spain under the Constitution.

Political pluralism was more problematic, not so much in its ideological dimension, as in its identity-territorial cleavage. Several generals and some businesspeople (who were former members of the military) pointed out that feelings of belonging to peripheral nationalisms were not only under-represented, but also inconvenient for the AFs: “not all political sensitivities are present in the AFs, as it is more aligned with people who believe in Spain as a unit” (Military 18). However, the military elite as a whole considers that any differences that may exist within the military are not a problem per se in terms of carrying out their tasks, as long as such diversity did not lead to a breakdown of the organisational culture within the institution. On the other hand, it would be a problem to establish quotas in order to ensure that specific groups or minorities were sufficiently represented in number, position or job; the respondents believed that such differences, could break the unity of the institution.

The military members’ claim that the AFs already reflects society clashes with the perception of the political elite, where contradictory views abounded. In fact, politicians hold a normative position on the need for this. This is not the case for the business community, who, in the spirit of pragmatism, perceived that pluralism is not something to be demanded or promoted in military institutions; these respondents did not believe that it is necessary for the military’s tasks.

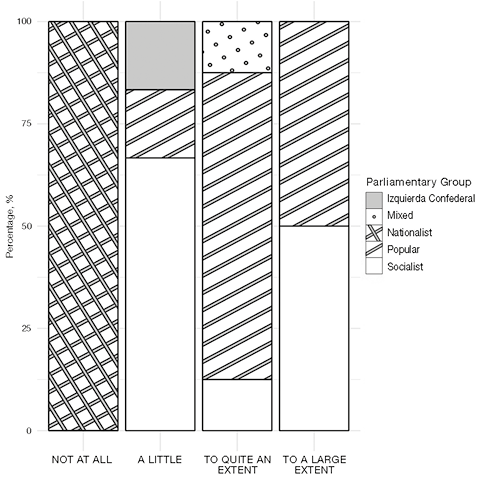

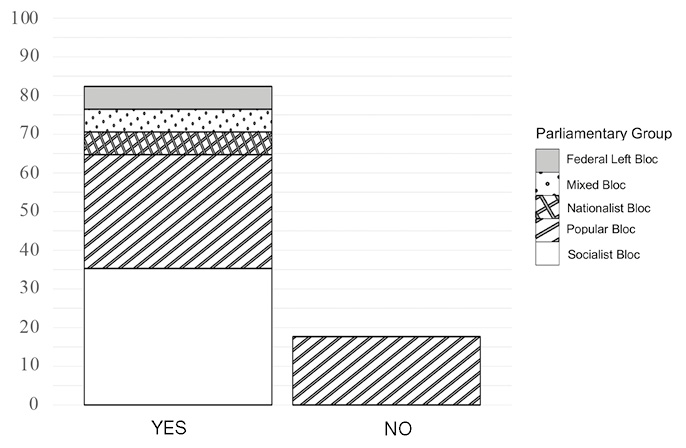

If we add to the spokespersons the answers of the rest of the parliamentarians surveyed, an analysis by parliamentary groups can be made. The representatives of the different nationalist groups, those of the Federated Left Bloc (Izquierda Confederada) and half of the socialist group were the most critical of the view that Spain’s diversity is reflected in the AFs (Figure 2). The Popular Party (Partido Popular) almost en bloc and the other half of the Socialist parliamentary group did believe, however, that the AFs currently reflect social plurality.

On the question of whether the AFs should be representative of society (Figure 3), the answer was overwhelmingly clear. All the parliamentary groups, with the exception of one third of the Partido Popular representatives, believed that the AFs should make an effort to reflect the plurality of Spanish society in all its facets (understood to mean in its recruitment and selection processes). In their view, the military would be better integrated if they reflected social plurality.

The elites believe that operations such as “Filomena” and “Balmis” have further improved the social image of the Armed Forces in Spain; “kindness in dealing with disasters sells more than the use of force” (Military 13).

This has two peculiarities: on the one hand, in October 2020 the majority of society (53 %) stated that the military’s performance during the COVID-19 pandemic had not changed their opinion of the AFs, despite recognising their positive intervention during the pandemic; only 39 % of the population acknowledged that the army’s performance had improved their opinion of the institution (Sociometrica, 2020). However, several interviewees did not bypass the fact that these missions were a long way from the natural purpose of the Armed Forces; “[citizens] have seen a part that is not really the essential mission of the Armed Forces” (Military Officer 16). While it is true that actions such as “Balmis” and interventions during the “Filomena” storm helped to make the AFs more visible, while projecting a facet of solidarity and usefulness, they did not contribute to the promotion of a defence culture among society, since they did not show what defence involves.

Operation “Balmis” and the Military Emergencies Unit (UME) help to improve the image of the AFs, but they improve it in a specific context, linked to civil protection. The role of the AFs is different. In Spain, there is no common nation, history or common values to protect, and this complicates the image of the AFs (Military 8).

There is also a critical view among the business community, as they argued that, despite society holding a positive image of the Armed Forces, there is still a rejection of greater investment and spending on defence in general, and on this industry in particular: “people can see its usefulness, but it seems that they don’t want to talk about the defence industry, nor about exports” (Businessperson 14).

Thus, there is a widespread perception that the armed forces are well regarded in society, but their primary role is not understood, nor is there a desire to increase military spending. Some of the politicians interviewed warned of the paradox: “it is likely that [citizens] have an old-fashioned and less modern image of the Armed Forces than what they actually are” (Politician 7); “Spanish society across the political spectrum has an unrealistic image of the Armed Forces, [...] lack of knowledge and [...]excluding, non-inclusive views” (Politician 11).

When asked whether these operations had improved the opinion of the military among the elites themselves or in the media, the answer, while affirmative, was clearly less emphatic than it had when asked about the impact on society. Those who perceived some improvement pointed to the visibility and impact of the UME (a unit that performs non-defence tasks). The participating business elites argued that the media were ignorant and did not inform citizens, and if they did report on the AFs, it was only anecdotally. The political elites were said to be influenced by the media’s lack of knowledge, sensationalism and information deficit.

If we focus on the responses of the colonels and parliamentarians surveyed, it can be seen that “Filomena” and “Balmis” were also considered to have had a very positive impact on improving the image of the Armed Forces. However, there are also two important nuances: the impact on improvement was tempered by almost twenty points when considering the elites, and by thirty when considering the military elites (Table 3).

Table 3. Impact of “Filomena” and “Balmis” (%)

|

Group Respondents |

They improved the image of the AFs held by |

||

|

Society |

Media |

Elites |

|

|

Military |

90.5 |

74.6 |

61.9 |

|

Politicians |

94.4 |

88.9 |

77.8 |

Source: Developed by the authors.

Half of the politicians interviewed said that it is not a prestigious profession. The half that believed it is prestigious thought so conditionally (“only in their environment”, “not in the Basque Country”, “not troops and lower ranks”). Slightly less than half of the military members interviewed did not think so either, and only a third of the executives held the same view. However, the latter believed that the professional prestige of the AFs has grown ostensibly in recent years. Some generals interviewed argued that this prestige was limited to their close family or professional environment, a belief that was shared by some of the politicians.

Among those who made a negative assessment of the AFs, the most common reason was the past:

[…] the armed forces have nothing to do with what they were before, when we did ‘the military service’, although some people insist on making it seem that way” (Businessperson 1).

But there were also many who attributed to peripheral nationalism or left-wing positions the fact that the AFs’ discredit was due to political identification by a certain social group or a specific ideology (Businessperson 7).

This position was in line with the social data available through the studies commissioned by the Ministry of Defence from Sociometrica (2019, 2020). In both waves, the opinion on this issue was not particularly prestigious, with a score of 5.5 out of 10 in 2019 and 5.7 in 2020; scores which decreased when compared to those of military personnel from neighbouring countries (3.7 in 2019 and 4 in 2020). People with a conservative ideology, older people, people with no education and people from the Canary Islands, Castilla La Mancha, Extremadura, Murcia, La Rioja and Cantabria had a substantially better opinion of military prestige.

An open-ended question on military strengths and weaknesses in the Sociometrics study (2020) provides some pointers as to the reasons that increase professional prestige and those that decrease it. Strengths included “humanitarian aid”, “public service”, “cooperation”, “preparedness” and “Balmis”. On the other hand, weaknesses included descriptions of the military as “anachronistic”, “fascist”, “arrogant”, “opaque”, “isolated” and “male chauvinistic”. It seems obvious that, as long as these prejudices remain as part of the society’s sentiments, it will be difficult for the AFs’ professional prestige to grow. All in all, the average prestige that Spanish society confers on the military was higher than that of the elites.

There is a need for research into CMR in Spain that examines the perceptions of the elites involved in defence policies, namely, decision-makers (politicians), practitioners (military) and stakeholders (military industry executives). Its relevance lies in whether or not there is a culture gap and if so, how it operates.

This research confirms the hypothesis that was initially formulated: there is a culture gap between the military and civilian elites in Spain, the civilian sector being understood as politicians and executives of the defence industry economic fabric. However, this gap is not homogeneous in all the variables analysed, since there are significant convergences in terms of the perception of the institution’s professional training, and a certain proximity regarding social image, professional prestige and the values that are considered pre-eminent in the military and in society. The main disagreement is over whether or not social cohesion measures are necessary and whether political, religious and social pluralism is present within the military.

Beyond the convergences, the differences emerge in the profound implications for the variables analysed: the participating military personnel and businesspeople think that the image of the AFs is highly conditioned to missions that are not, strictly speaking, part of national defence, but rather of civil protection. They believe that the military institution is only highly valued when engaged in disaster management, emergencies and as “armies for peace”.

The gap is at its widest when referring to the need to promote cohesion measures between the AFs and society. An area where military and economic elites perceive a greater need for action than political elites. Conflict between elites can be observed in relation to whether the AFs could or should reflect pluralism. Firstly, because it is understood differently by the various elites: the military only circumscribe it to religious parameters, while the civilian elites attribute it above all to political (identity and gender) aspects; and secondly, because the political elites believe it is essential for the military to be an accurate reflection of Spain’s socio-political pluralism, but the military elites do not.

The research highlights how the current situation of the CMR in Spain shies away from both Janowitz’s model, where the AFs and society should share the same values, even if the political elites are more inclined to do so. It is also removed from Huntington’s model of the military as an isolated collective, with its own exclusive values. On the contrary, there is a convergence between civilians and the military in terms of the social desirability of certain values. This assessment is important, as it constitutes a compromise between the integration proposed by the first model and the separation of the second.

The results in the Spanish case invite us to rethink the concept of culture gap, insofar as antagonism can be observed in its two dimensions. Regarding the first dimension, there are no shared values among the elites. This is probably explained by both the process of military civilianization and effective civilian control of the AFs. The second dimension, perceptions, presented a significant distance between elites, but also dissimilar intra-elite preferences. In this sense, the greater the political normativity implied by the premise in question, the greater the divergences.

Once the components of the gap and their contents have been ascertained, future avenues of research should delve deeper into their causes. An interesting question arising from this research is where to place defence industry executives, as several of them are former military personnel. Their current professional duties locate them within the civilian sphere; however, their former employment might influence the shaping of their perceptions and interpretations, leading to permeation between military and business elites. This would have an impact on the civil-military gap, as it could result in a reduction of the gap caused by the bias due to the military background of its members. This is also a major factor, as it directly affects the relations between the defence technological-industrial base and policy-makers.

Allen, John and Moskos, Charles (1997). Civil-Military Relations after the Cold War. En: A. Bebler (ed.). Civil-Military Relations in Post-Communist States. Central and Eastern Europe in Transition. London: Praeger.

Avant, Deborah (1998). “Conflicting Indicators of «Crisis» in American Civil-military Relations”. Armed Forces & Society, 24(3): 375-387. doi: 10.1177/0095327X9802400303

Barany, Zoltan (2012). The soldier and The Changing State: Building Democratic Armies in Africa, Asia, Europe and the America. Princeton: Princenton University Press.

Benoit, Kennet; Watanabe, Kohei; Wang, Haiyan; Nulty, Paul; Obeng, Adam; Müller, Stefan and Matsuo, Akitaka (2018). “quanteda: An R Package for the Quantitative Analysis of Textual Data”. Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30): 774. doi: 10.21105/joss.00774

Bland, Douglas (1999). “Managing the ‘Expert’ Problem in Civil-Military Relations”. European Security, 8(3): 24-43. doi: 10.1080/09662839908407415

Bueno, Alberto (2019). “La evolución de los estudios estratégicos en la comunidad académica española: análisis de su agenda de investigación (1978-2018)”. Revista Española de Ciencia Política, 51: 177-203. doi: 10.21308/recp.51.07

Bueno, Alberto; Calatrava, Adolfo; Remiro, Luis and Martínez, Rafael (2023). “Cultura de defensa en España: una nueva propuesta teórico-conceptual”. Revista de Pensamiento Estratégico y Seguridad CISDE, 8(1): 71-91.

Caforio, Giugseppe (2007). Cultural Differences between the Military and the parent Society in Democratic Countries. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Calduch, Rafael (2018). Cultura de defensa. In: J. R. Argumosa (ed.). Defensa, Estado y Sociedad: el caso de España. España: Instituto Europeo de Estudios Internacionales.

Chaqués-Bonafont, Laura; Palau, Anna M. and Baumgartner, Frank R. (2015). Agenda Dynamics in Spain. Houndmills: Palgrave MacMillan.

Cicuéndez Santamaría, Ruth (2017). “Las preferencias de gasto público de los españoles: ¿interés propio o valores?”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 160: 19-38. doi: 10.5477/cis/reis.160.19

Cohen, Eliot A. (2000). “Why the Gap Matters”. The National Interest, 61: 38-48.

Cohen, Amichai and Cohen, Stuart Alan (2022). “Beyond the Conventional Civil–military ‘Gap’: Cleavages and Convergences in Israel”. Armed Forces & Society, 48(1): 164-184. doi: 10.1177/0095327X20903072

Collins, Joseph J. and Holsti, Ole R. (1999). “Civil-military Relations: How Wide is the Gap?”. International Security, 24(2): 199-207. doi: 10.1162/016228899560121

Díez-Nicolás, Juan (1986). “La transición política y la opinión pública española ante los problemas de la defensa y hacia las Fuerzas Armadas”. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 36: 13-24. doi: 10.2307/40183243

Díez-Nicolás, Juan (1999). Identidad Nacional y Cultura de Defensa. Madrid: Síntesis.

Díez-Nicolás, Juan (2006). La opinión pública española y la política exterior y de seguridad. Madrid: INCIPE.

Feaver, Peter (2003). “The Civil–military Gap in Comparative Perspective”. Journal of Strategic Studies, 26(2): 1-5. doi: 10.1080/01402390412331302945

Feaver, Peter D. and Kohn, Richard H. (2000). “The Gap: Soldiers, Civilians and their Mutual Misunderstanding”. The National Interest, 61: 29-37.

Feaver, Peter D. and Kohn, Richard H. (2001). Soldiers and civilians: The Civil-Military Gap and American National Security. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Fitch, John S. (1998). The Armed Forces and Democracy in Latin America. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Forster, Anthony (2012). “The Military Covenant and British Civil–military Relations: Letting the Genie out of the Bottle”. Armed Forces & Society, 38(2): 273-290. doi: 10.1177/0095327X11398448

Geertz, Clifford (1997). La interpretación de las culturas. Barcelona: Gedisa Editorial.

Golby, James; Feaver, Peter and Dropp, Kyle (2018). “Elite Military Cues and Public Opinion about the use of Military Force”. Armed Forces & Society, 44(1): 44-71. doi: 10.1177/0095327X16687067

Grün, Bettina and Hornik, Kurt (2011). “Topicmodels: An R Package for Fitting Topic Models”. Journal of Statistical Software, 40(13): 1–30. doi: 10.18637/jss.v040.i13

Huntington, Samuel (1957). The Soldier and the State: The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Janowitz, Morris (1960). The Professional Soldier. Glencoe: Free Press.

Kertzer, Joshua D. and Zeitzoff, Thomas (2017). “A Bottom‐up Theory of Public Opinion about Foreign Policy”. American Journal of Political Science, 61(3): 543-558. doi: 10.1111/ajps.12314

Kuehn, David and Lorenz, Philip (2011). “Explaining Civil-military Relations in New Democracies: Structure, Agency and Theory Development”. Asian Journal of Political Science, 19(3): 231-249. doi: 10.1080/02185377.2011.628145

Levy, Yagil (2012). “A Revised Model of Civilian Control of the Military: The Interaction between the Republican Exchange and the Control Exchange”. Armed Forces & Society, 38(4): 529-556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095327X12439384

Luttwak, Edward N. (1995). “Toward Post-heroic Warfare”. Foreign Affairs, 74(3): 109-122. doi: 10.2307/20047127

Martínez, Rafael (2007). Los mandos de las fuerzas armadas españolas del siglo xxi. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Martínez, Rafael (2008). “Les forces armées espagnoles: dernier bastion du franquisme?”. Revue Internationale de Politique Iomparée, 15(1) : 35-53.

Martínez, Rafael (2020). The Spanish Armed Forces. En: D. Muro and I. Lago (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Spanish Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Martínez, Rafael (2022). “Las Fuerzas Armadas y los roles a evitar después de la pandemia”. Revista de Occidente, 474: 9-22.

Martínez, Rafael (2024). Knowledge, Expertise, and Effectiveness. In: A. Croissant, D. Kuehn y D. Pion-Berlin (eds.). Handbook of Civil-Military Relations. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Martínez, Rafael and Díaz, Antonio M. (2005). Spain: An equation with Difficult Solutions. In: G. Caforio and G. Kümmel (eds.). Military Missions and Their Implications Reconsidered: The Aftermath of September 11th. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Martínez, Rafael and Díaz, Antonio M. (2007). Threat Perception: New Risks, New Threats and New Missions. In: G. Caforio (ed.). Cultural Differences between the Military and Parent Society in Democratic Countries. Bingley: Emerald.

Martínez, Rafael and Durán, Marién (2017). “International Missions as a Way to Improve Civil–military Relations: the Spanish Case (1989–2015)”. Democracy and Security, 13(1): 1-23. doi: 10.1080/17419166.2016.1236690

Martínez, Rafael and Padilla, Fernando J. (2021). Spain: The Long Road from an Interventionist Army to Democratic and Modern Armed Forces. In: W. R. Thompson (ed.). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of the Military in Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mathieu, Ilinca (2015). Opinions publiques et action stratégique. In: J. Henrotin, O. Schmitt and S. Taillat (dirs.). Guerre et Stratégie. Approches, concepts. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Mintzberg, Henry (2012). La estructuración de las organizaciones. Barcelona: Ariel.

Moskos, Charles and Wood, Frank R. (1988). The Military. More than just a Job? London: Pergamon-Brassey’s International Defense Publishers.

Mukherjee, Anit and Pion-Berlin, David (2022). “The Fulcrum of Democratic Civilian Control: Re-imagining the Role of Defence Ministries”. Journal of Strategic Studies, 45(6-7): 783-797. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2022.2127094

Navajas, Carlos (2018). Democratización, profesionalización y crisis. Las Fuerzas Armadas y la sociedad en la España democrática. Madrid: Biblioteca Nueva.

Nielsen, Suzanne C. (2002). “Civil-Military Relations

Theory and Military Effectiveness”. Policy & Management Review, 10(2): 61-84.

Nielsen, Suzanne C. and Snider, Don (2009). American Civil–Military Relations: The Soldier and the State in a New Era. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Pion-Berlin, David and Martínez, Rafael (2017). Soldiers, Politicians, and Civilians: Reforming Civil-military Relations in Democratic Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

R Core Team (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Viena, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available at: https://www.R-project.org/, access June 11, 2024.

Rahbek-Clemmensen, John; Archer, Emerald M.; Barr, Joh; Belkin, Aaron; Guerrero, Mario; Hall, Cameron and Swain, Katie E. O. (2012). “Conceptualizing the Civil-Military Gap: A Research Note”. Armed Forces & Society, 38(4): 669-678. doi: 10.1177/0095327X12456509

Ruffa, Chiara (2017). “Military Cultures and Force Employment in Peace Operations”. Security Studies, 26(3): 391-422. doi: 10.1080/09636412.2017.1306393

Scott, John (2008). “Modes of Power and the Re-Conceptualization of Elites”. The Sociological Review, 56(1): 25–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2008.00760.x

Serra, Narcís (2008). La transición militar: reflexiones en torno a la reforma democrática de la Fuerza Armada. Barcelona: Debate.

SocioMétrica (2019). Observatorio de Opinión Pública sobre las actividades, planes y programas del Plan Cultural de Cultura y Conciencia de Defensa - Ministerio de Defensa (Trabajo de Campo, análisis e informe). Madrid: SocioMétrica.

SocioMétrica (2020). Observatorio de Opinión Pública sobre las actividades, planes y programas del Plan Cultural de Cultura y Conciencia de Defensa - Ministerio de Defensa. (Resultados definitivos al Informe 2020, - 1.ª y 2.ª Oleada). Madrid: SocioMétrica.

Szayna, Thomas S.; McCarthy, Kevin F.; Sollinger, Jerry M.; Demaine, Linda J.; Marquis, Jefferson P. and Steele, Brett (2007). The Civil-military Gap in the United States: Does It Exist, Why, and Does It Matter? Santa Monica: Rand Corporation.

Villalaín Benito, José L. (1992). “Los valores predominantes en la sociedad española de los noventa: su progresiva homogeneización y polarización en el mundo de lo privado”. Revista de Educación, 297: 275–291.

RECEPTION: July 12, 2023

REVIEW: January 31, 2024

ACCEPTANCE: June 10, 2024

1 The authors would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which have improved the article. They are also grateful to Xavier Fernández i Marin for their technical support in text analysis. They also wish to thank the participants in the respective working groups of the First Civil-Military Sociology Congress (I Congreso Cívico-Militar de Sociología) and the 16th Congress of the Spanish Association of Political and Administration Sciences (xvi Congreso de la Asociación Española de Ciencia Política y de la Administración) for their comments, as well as the entire “Repensando el papel de las Fuerzas Armadas ante los nuevos desafíos a la seguridad (REPENFAS21)” project research team, as the different results obtained were the fruit of the reflections of all the team members’.

Funding: This article has been funded by the Spanish State Research Agency (Agencia Estatal de Investigación Española) under “Repensando el papel de las Fuerzas Armadas ante los nuevos desafíos a la seguridad (REPENFAS21)”, PID2019-108036GB-I00/AEI/10.1339/501100011033.

2 Surveys nos. 2234, 2277, 2317, 2379, 2447, 2447, 2592, 2680, 2825, 2912, 2998, 3110 and 3118.

3 Their study included two more gaps that will not be used here: public policy preferences and institutional context.

4 CIS survey no. 1518 (1986).

5 CIS Surveys nos. 1518 (1986), 1636 (1986) and 1762 (1988).

6 CIS survey no. 1784 (1989).

7 CIS survey no. 1870 (1990).

8 CIS Survey no. 3080 (2015).

9 While the comparison between the elites and society is interesting, it is not the subject of this article. However, a good analysis of the evolution of Spaniards' perceptions, working with the CIS series of surveys on national defence and the armed forces, can be found in Martínez (2020).

10 All Annexes can be consulted at: https://www.dropbox.com/scl/fo/r844nm7mw9ocn4kio3mlr/h?rlkey=8gle3kpv4anyqd5q8kv3ulo9k&dl=0

11 When potential interviewees were contacted, the project and the collaboration required were explained to them (Annex 3). At the time of the interview, they were given an information sheet and a short text was read to them to obtain their informed consent (Annexes 4 and 5.1, 5.2, 5.3).

12 In all cases, the generic masculine (in the Spanish version of the interviews) was used for references regardless of gender, also to reinforce anonymity. Of the 46 interviewees, only 3 were women.

13 The percentage breakdown was: 43 % from the Army, 17 % from the Navy, 24 % from the Air and Space Forces, and 16 % from the Common Corps of the Armed Forces.

14 They were invited to respond in writing (Annex 9). Responses were received from 50 % of the military members, from 14 % of the executives and from 17 % of the politicians contacted.